A flash flood near the Great Fall nearly swept away Charbonneau, Sacagawea, Jean Baptiste, York, and William Clark.

There seems to be a sertain fatality attached

to the neighbourhood of these falls, for there is always

a chapter of accedents prepared for us

during our residence at them.

Breathless Moment

Charles M. Russell (1903), for Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark. See also Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”.

The famous Western artist Charles M. Russell (1864-1826) painted this scene showing Charbonneau and Clark helping Sacagawea escape the water rising in that “deep rivene” above the Grand Fall of the Missouri.[1]This is one of three paintings Olin D. Wheeler commissioned from Charles Russell. It was published as a grayscale halftone in Wheeler’s two-volume Trail of Lewis and Clark, in 1904. The … Continue reading The young mother is clutching her four-month-old infant son, who is securely bound in a Plains Indian cradleboard. That is what most writers and artists have assumed Lewis was referring to with the word bier. But since she was captured by Hidatsas at about age 12, and passed through puberty among them, it is believed that Sacagawea was prepared for adulthood–and motherhood–according to Hidatsa ways. Therefore, most Hidatsa elders have long maintained she would have wrapped her baby in a shawl and carried him facing forward over one of her shoulders, as shown in the coin below, and in the statue of her on the Capitol grounds in Bismarck, North Dakota.

The chapter of knowledge is a very short, but the chapter of accidents is a very long one,” wrote the famous British memoirist Philip Dormer Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield (1694-1773) to a friend in 1753. “I will keep dipping in it,” he continued, in reference to his own growing deafness, “for sometimes a concurrence of unknown and unforeseen circumstances, in the medicine and the disease, may produce an unexpected and lucky hit.”[2]John Bradshaw, ed., The Letters of Philip Dormer Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield (3 vols., London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1892), 3:1054. Evidently Lewis was familiar with Lord Chesterfield’s famous aphorism, for he himself referred to “a chapter of accedents” now and then, though more often inverted into the sense of a near calamity than as a “lucky hit.”

Of all the near-calamities the Corps of Discovery experienced, individually or collectively, none was more dire than the one that occurred on 29 June 1805 in a normally dry ravine on the south side of the Missouri River a short distance above the Great Fall. The principals were Charbonneau, Sacagawea, Jean Baptiste, York, and William Clark. Characteristically, Lewis’s account of the gully-washer is more dramatic than Clark’s own matter-of-fact report:

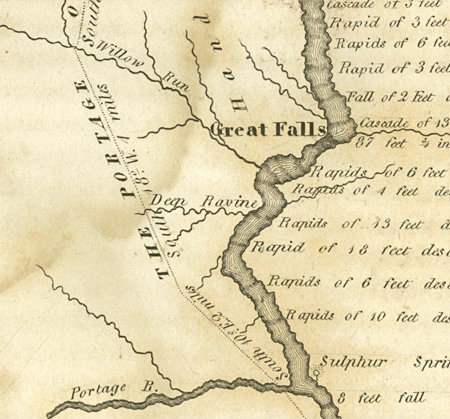

he determined himself to pass by the way of the river to camp in order to supply the deficitncy of some notes and remarks which he had made as he first ascended the river but which he had unfortunately lost. accordingly he left one man at Willow run to guard the baggage took with him his black man York, Sharbono and his indian woman. on his arrival at the falls he perceived a very black cloud rising in the West which threatened immediate rain; he looked about for a shelter but could find none without being in great danger of being blown into the river should the wind prove as violent as it sometimes is on those occasions in these plains; at length about a 1/4 of a mile above the falls he discovered a deep rivene where there were some shelving rocks under which he took shelter near the river with Sharbono and the Indian woman; laying their guns compass &c. under a shelving rock on the upper side of the rivene where they were perfectly secure from the rain.

the first shower was moderate accompanyed by a violent rain the effects of which they did but little feel; soon after a most violent torrent of rain decended accomapnyed with hail; the rain appeared to decend in a body and instantly collected in the rivene and came down in a roling torrent with irrisistable force driving rocks mud and everything before it which opposed it’s passage. Capt. C. fortunately discovered it a moment before it reached them and seizing his gun and shot pouch with his left hand with the right he assisted himself up the steep bluff shoving occasionaly the Indian woman before him who had her child in her arms; Sharbono had the woman by the hand indeavouring to pull her up the hill but was so much frightened that he remained frequently motionless and but for Capt. C. both himself and his [wo]man and child must have perished.

so suddon was the rise of the water that before Capt C could reach his gun and begin to ascend the bank it was up to his waist and wet his watch; and he could scarcely ascend faster than it arrose till it had obtained the debth of 15 feet with a current tremendious to behold. one moment longer & it would have swept them into the river just above the great cataract of 87 feet where they must have inevitably perished.

Sarbono lost his gun shot pouch, horn, tomahawk, and my wiping rod; Capt. Clark his Umbrella and compas or circumferenter. they fortunately arrived on the plain safe, where they found the black man, York, in surch of them; york had seperated form them a little while before the storm, in pursuit of some buffaloe and had not seen them enter the rivene; when this gust came on he returned in surch of them & not being able to find them for some time was much allarmed.

the bier in which the woman carrys her child and all it’s cloaths wer swept away as they lay at her feet she having time only to grasp her child; the infant was therefore very cold and the woman also who had just recovered from a severe indisposition was also wet and cold, Capt C. therefore relinquished his intended rout and returned to the camp at willow run[3]In Virginia and the Carolinas the term “run” was applied to a stream fed mainly by rain and snow. in order also to obtain dry cloathes for himself and directed them to follow him.

The next day, two men sent back to the ravine on a search “returned with the compas which they found covered in the mud and sand near the mouth of the rivene the other articles were irrecoverably lost.” Needless to say, all were relieved that lives had been spared.

Aside from adding a major episode to the expedition’s long and intricate “chapter of accidents,” this story provides two exceptional opportunities to learn more about Lewis and Clark and their times. First it suggests a study of a word that frequently appeared in the journals, but is now widely misunderstood—bier. (See Mosquito Netting.) Second, it invites an inquiry into the history of an ordinary object that apparently was in Clark’s personal baggage, but which probably would have gone entirely unmentioned except for the fact that Clark lost it—his umbrella. (See Clark’s Umbrella).

Notes

| ↑1 | This is one of three paintings Olin D. Wheeler commissioned from Charles Russell. It was published as a grayscale halftone in Wheeler’s two-volume Trail of Lewis and Clark, in 1904. The location of the original watercolor is not known. The same painting appeared as the frontispiece of Stories of the Republic (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1912). Charley Russell created about 20 paintings and drawings specifically related the Lewis and Clark expedition, more than any other artist of his time. Elizabeth A. Dear, The Grand Expedition of Lewis & Clark as Seen by C.M. Russell (Helena, Montana: C.M. Russell Museum, 2000), 3-7, 19. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | John Bradshaw, ed., The Letters of Philip Dormer Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield (3 vols., London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1892), 3:1054. |

| ↑3 | In Virginia and the Carolinas the term “run” was applied to a stream fed mainly by rain and snow. |