The Chinookan Peoples had learned long ago how to cope with the physics of fire management and fresh air circulation in their houses.

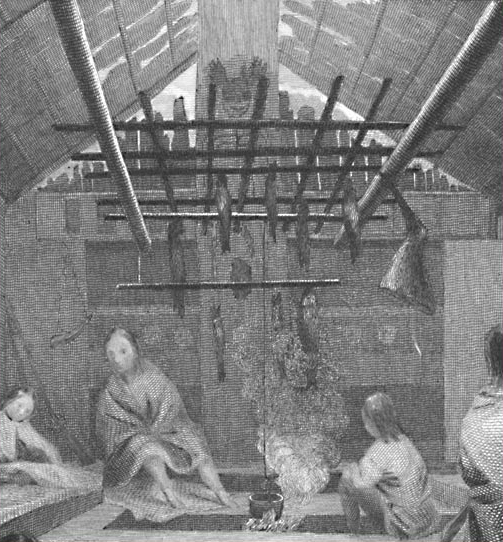

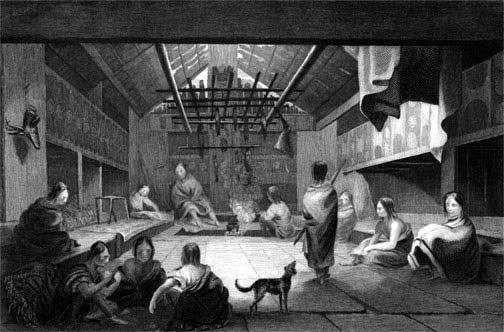

Detail from “Interior of a Chinook House”

by Alfred T. Agate (1812–1846)

Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition (6 vols, 1844-45), Vol. 4, p. 341. Archives and Special Collections, Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library, University of Montana.

American artist Alfred Agate (1812-1846) was the official portrait and botanical illustrator for the United States Exploring Expedition of 1838-1842, commanded by the naval officer Charles Wilkes (1798-1877). Agate created 172 of the 342 drawings and paintings that were reproduced as lithographs in Wilkes’s six-volume report. It is known that he used an optical tracing aid called a camera lucida, which was similar to the camera obscura in effect, but more easily portable. Both instruments reflected an image or view on a drawing surface such as a piece of paper, where it could be copied with a pencil.

The first version of the camera lucida was patented by the English physicist William Wollaston in 1807, but new models based on the same principles are still in use for certain types of illustration. In fact, a digital Camera Lucida application for the iPhone appeared on the market in 2011. As of the present date, version 4 of the iPhone App supports landscape mode and can be used to capture panoramic scenes. Whether Agate could have used his instrument to capture the interior of this large Pacific Coast plank house is questionable.

Managing Smoke

It was Sgt. Gass who reported on a situation that seriously threatened to put a damper on their Christmas jollity: “We found our huts smoked; there being no chimneys in them except in the officers’ rooms. The men were therefore employed, except some hunters who went out, in making chimnies to the huts.” Perhaps chimneys had been omitted because the Indians from the Great Falls all the way to the coast didn’t use them, and didn’t appear to be seriously troubled by smoke, so the easterners may have concluded that hereabouts a hole in the roof above the fire would be enough to keep the inside air breathable. But the Chinookan Peoples had learned long ago how to cope with the physics of fire management and fresh air circulation in their houses. For one thing, the soldiers strove to make their huts snug and, as Clark proudly witnessed, they succeeded. They daubed mud in the chinks between the logs to keep out the wind. The Indians, for their part, allowed their houses to breathe.

Over a period of many generations, perhaps hundreds or even thousands of years, coastal Natives had devised simple, reliable ways of manipulating the balance of atmospheric pressure, temperature and air flow in what is now called the “stack effect.” In terms of the Indians’ practices, that meant that as the warming or cooking fire heats the room above the outside temperature, the warm air rises, decreasing the atmospheric pressure toward the floor, and raising it toward the ceiling. The horizontal zone in which the atmospheric pressure inside is equal to that outdoors, is a neutral pressure plane that holds the smoke indoors, close to the fire. In thee, with 8 men in each of the two 15 by 16-foot rooms and 10 in the 18 x 15-foot room, the frequent opening of doors would have created strong downdrafts and increased the concentration of smoke in the rooms, especially when the wind was blowing hard. Heating and ventilating are much easier to control with a properly designed chimney and flue. Indeed, as one authority has declared, “The chimney is the engine that drives a wood heat system.”[1]The Wood Heat Organization Inc., http://www.woodheat.org/all-about-chimneys.html (Retrieved 21 March 2013).

The opening in the highest part of the gable roof admits light (along with some rain), and draws the smoke from the fire pit. Two sturdy log beams span the length of the house, supporting the wooden grid from which are suspended the haunch of an elk plus several fish of various sizes in the flavoring effect of the rising smoke. The lofty grid also enabled persons to reach the roof planks to rearrange them so as to increase or decrease the fire’s draft. A single pole suspended from the two beams serves as a crank (without a handle) with which the cooking pot could be raised or lowered relative to the fire’s heat.

Games of Amusement and Risk

The three figures in the lower foreground of Agate’s drawing appear to be playing the game Meriwether Lewis described in his journal for 2 February 1806:

One of the games of amusement and risk of the Indians of this neighbourhood, like that of the Shosones, consists in hiding in the hand some small article about the size of a bean. This they throw from one hand to the other with great dexterity accompanying their opperations with a particular song which seems to have been addapted to the game. When the individual who holds the piece has amus-ed himself sufficiently by exchanging it from one hand to the other, he holds out his hands for his competitors to guess which hand contains the piece. If they hit on the hand which contains the peice they win the wager; otherwise they lose. The individual who holds the piece is a kind of banker and plays for the time being against all the others in the room. When he has lost all the property which he has to venture, or thinks proper at any time, he transfers the piece to some other who then also becomes banker.

A similar game was played–and still is–among all Indian peoples in North America.[2]Stewart Culin, Games of the North American Indians: Volume 1, Games of Chance (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992).

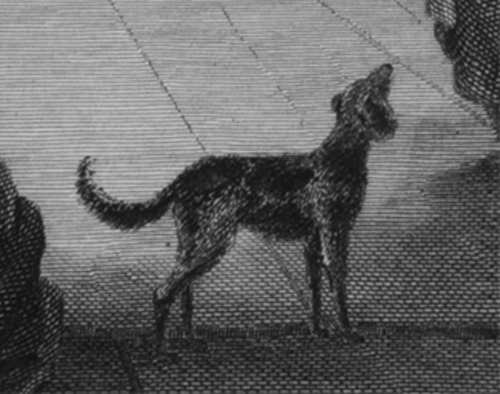

The Indian Dog

This dog, drawn by Alfred Agate (1812-1846), who was one of two prominent American artists who accompanied the U.S. Exploring Expedition commanded by Lieutenant Charles Wilkes in 1838-1842, somewhat resembles Lewis’s description of the typical dog seen among the Indians in the vicinity of Fort Clatsop. (Moulton, Journals, 16 February 1806.)

The Indian dog is usually small or much more so than the common cur. they are party coloured [parti-colored; having patches of contrasting color; pied]; black white brown and brindle are the most usual colours. the head is long and nose pointed eyes small, ears erect and pointed like those of the wolf, hair short and smooth except on the tail where it is as long as that of the curdog and streight. the natives [Clatsops] do not eat them nor appear to make any other use of them but in hunting the Elk.

Paul Kane’s Interpretation

Klickitat Lodge

by Paul Kane (1810–1871)

Watercolor on paper (1847). Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Ontario, No. 46.15.221.

Whereas, aside from the haphazard arrangement of planks in the gable and roof, Alfred Agate’s impression of a Chinook plank house appears very neat and orderly–”classy,” one might say, especially in the Klikitat house depicted by Paul Kane looks more casual, even haphazard, to put it kindly, at least from the outside.

In his journal, the Kane described the abodes of the Chinookan Peoples as follows:

During the season the Chinooks are engaged in gathering camas and fishing, they live in lodges constructed by means of a few poles covered with mats made of rushes, which can be easily moved from place to place, but in the villages they build permanent huts of spit cedar boards. Having selected a dry place for the hut, a hole is dug about three feet deep, and about twenty feet square. Round the sides of square cedar boards are sunk and fastened together with cords and twisted roots, rising about four feet above the outer level; two posts are sunk at the middle of each end with a crotch at the top, on which the lodge pole is laid, and boards are laid from thence to the top of the upright boards fastened in the same manner. Round the interior are erected sleeping places, one above another, something like the berths in a vessel, but larger. In the centre of this lodge the fire is made, and the smoke escapes through a hole left in the roof for that purpose.[3]Paul Kane, Wanderings of an Artist Among the Indians of North America (London: Longman, Brown Green, Longmans, and Roberts, 1859), 187.

The Scottish naturalist Archibald Menzies (1754–1842), who accompanied Captain George Vancouver on his voyage around the world in 1791–1795, wrote a more laconic word-picture of a scene that caught his attention in the Gulf of Georgia, in mid-June of 1792:

[T]he appearance of smoke issuing from a part of the wood on an Island before us induced us to land at a place where we found four or five families of the Natives variously occupied in a few temporary huts formd in the slightest & most careless manner by fastening together some rough sticks & throwing over them some pieces of Mats of Bark of Trees so partially as to form but a very indifferent shelter from the inclemency of the weather.[4]E. V. Newcombe, ed., Menzies’ Journal of Vancouver’s Voyage, April to October 1792 (Victoria, BC: William J. Cullin, 1923), 58. Internet Archive.

Notes

| ↑1 | The Wood Heat Organization Inc., http://www.woodheat.org/all-about-chimneys.html (Retrieved 21 March 2013). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Stewart Culin, Games of the North American Indians: Volume 1, Games of Chance (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992). |

| ↑3 | Paul Kane, Wanderings of an Artist Among the Indians of North America (London: Longman, Brown Green, Longmans, and Roberts, 1859), 187. |

| ↑4 | E. V. Newcombe, ed., Menzies’ Journal of Vancouver’s Voyage, April to October 1792 (Victoria, BC: William J. Cullin, 1923), 58. Internet Archive. |