The Tillamooks, cordial hosts and friends to the visiting Americans in 1806, may have numbered about 2,200 persons at that time. By 1841 sexually transmitted diseases, smallpox, measles, and influenza epidemics contracted from white traders reduced them to about 400 souls. As immigrant settlement increased, the Indians were even attacked by self-styled white “exterminators.”

Welcoming Pole at NeCus’ Park

by Guy Capoeman

Courtesy National Park Service, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

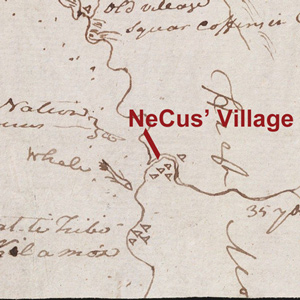

NeCus’ Village was a thriving village at Ecola Creek, and the Lewis and Clark Expedition journals provide the first written account of this community. It is here that Clark and his party saw the whale and Hugh Hall‘s life was saved by the efforts of a Tillamook woman. The 10-foot cedar “welcoming pole” shown above is of a Clatsop man, and the park was developed in cooperation with the Clatsop-Nehalem Confederated Tribes.[1]“NeCus’ Park,” National Park Service, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, www.nps.gov/places/necus-park.htm accessed 4 January 2023; “A Village on the Ecola Shore: … Continue reading

Early in the 1850s most of the survivors, along with the remnants of about 15 other Indian nations in northwestern Oregon, were marched from their homes to a 69,000-acre Coastal Reservation on Oregon’s Salmon River, 60 miles south of the Columbia and 20 miles inland.

The General Allotment (Dawes) Act of 1887, which gave 160 acres of land to the head of each Indian household, was intended to ease the River Indians into the American mainstream as middle class farmers and, in the time-honored conservative catch-phrase, “get the government out of their lives.” However, it also required that “surplus” reservation land be surrendered to the U.S. Government. By the early 1950s there were only 597 acres left in their reservation and so, in the spirit of economy, a government-appointed trustee was directed to dispose of them. That he did—to private interests, for $1.10 per acre; the income was distributed to tribal members at $35 per person. In 1970, tribal property consisted of 2.5 acres and a tool shed next to the tribal cemetery.

In a gesture of reconciliation, the Restoration Act of 1983 restored recognition to the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde. In 1988 the Grand Ronde Reservation Act gave back to the tribe 9,811 acres of public timberland, on three conditions: First, that the tribes refrain from competing with the local timber market for 20 years; second, that 30 percent of any income from the timber be used for tribal economic development; and third, that the tribe pay 20 years’ worth of back taxes to the two counties in which the timberland lay.

For Further Reading:

Jan Halliday & Gail Chehak, Native Peoples of the Northwest (Seattle: Sasquatch Books, 1986), pp. 140-42.

William Canby, Jr., American Indian Law (2nd ed., St. Paul: West Publishing Company, 1991).

Sharon Malinowski, et al., eds., The Gale Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes (4 vols., Detroit: Gale Research, 1998).

Selected Encounters

January 3, 1806

Fresh whale blubber

Fort Clatsop, Astoria, OR Visiting Clatsops sell roots, berries, fresh whale blubber, and dogs. Three hunters return empty-handed, and two men are sent to bring Willard and Weiser back from the salt maker’s camp.

January 6, 1806

Sacagawea's plea

Fort Clatsop, Astoria, OR Sacagawea pleads to be permitted to see the beached whale, and her wish is “indulged.” Lewis describes the status of Chinookan women and laments the expedition’s paucity of trade goods.

January 7, 1806

Clark's Point of View

Fort Clatsop and Tillamook Head, OR Clark’s group travels several miles along the beach to reach the Salt Works. From there, they climb up the very “Pe Shack” (bad) headland they called “Clark’s Point of View.”

After passing the salt works and continuing along the “round Slippery Stones under a high hill,” Clark related, “my guide made a Sudin halt, pointed to the top of the mountain and uttered the word Pe Shack which means bad, and made Signs that we . . . must pass over that mountain.

January 8, 1806

A night at Ecola

Fort Clatsop and Ecola Creek, OR From Clark’s Point of View, the travelers see the “grandest and most pleasing prospects.” At Ecola, Tillamook Indians trade a little blubber. In the evening, McNeal’s life is threatened.

By the time Clark and his party got to present-day Cannon Beach, Oregon, on 8 January 1806, the locals had picked the dead whale’s 105-foot-long carcass clean.

Before the resort town of Cannon Beach, Oregon, a Tillamook tribal village—NeCus’—sat along the tiny brackish bay where Ecola Creek crosses the sandy beach. The Lewis and Clark Expedition journals provide a tantalizing but fragmentary glimpse of this community.

January 11, 1806

Lost Chinookan canoe

Fort Clatsop, OR Careless paddlers fail to properly secure a canoe the previous night, and it floats away with the tide. Several men search for the lost Chinookan canoe without any luck. In Washington City, President Jefferson says the visiting Indian delegation will soon leave.

January 13, 1806

Running out of candles

Fort Clatsop, Astoria, OR Elk tallow is rendered to make new candles, Lewis finds that the area’s elk do not have enough fat to make a sufficient supply, and President Jefferson writes to Lewis’s mother with news of the expedition’s progress.

January 23, 1806

A lack of brains

Fort Clatsop, OR Lewis laments a “want of [animal] branes” with which to make leather. He also says that the giant horsetail plant root, eaten by the Clatsops, tastes insipid.

January 25, 1806

Critical updates

Fort Clatsop, Astoria, OR The captains receive several updates: a report from the salt makers, the location of two previously missing hunters, and new information about the Tillamooks. Lewis begins his dissertation on local fruits and berries.

March 18, 1806

Stealing a canoe

Fort Clatsop, OR After stealing a canoe, soldiers hide it near the fort. The captains write a short description of the expedition with the names of each member, and they distribute copies among the Indians.

March 21, 1806

Delayed by weather

Fort Clatsop, Astoria, OR Bad weather prevents the expedition from leaving for home. Provisions are low, so during the weather delay, hunters are dispatched without success.

March 22, 1806

Giving away the fort

Fort Clatsop, OR In addition to giving away the fort, hunters are sent up the Columbia to hunt ahead of tomorrow’s planned departure.

Notes

| ↑1 | “NeCus’ Park,” National Park Service, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, www.nps.gov/places/necus-park.htm accessed 4 January 2023; “A Village on the Ecola Shore: Revisiting the Lives and Landscapes of the “No-Cost Tribe of the Kil a mox Nation,” We Proceeded On 48, no. 1 (February 2022): 20–29. |

|---|