Breathless Moment

Charles M. Russell (1903), for Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark. See also Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”.

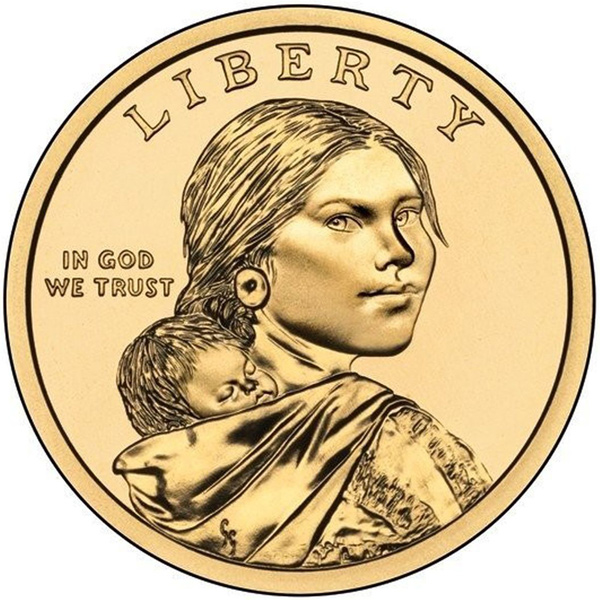

The famous Western artist Charles M. Russell (1864-1826) painted this scene showing Toussaint Charbonneau and Clark helping Sacagawea escape the water rising in that “deep rivene” above the Grand Fall of the Missouri.[2]This is one of three paintings Olin D. Wheeler commissioned from Charles Russell. It was published as a grayscale halftone in Wheeler’s two-volume Trail of Lewis and Clark, in 1904. The … Continue reading The young mother is clutching her four-month-old infant son, who is securely bound in a Plains Indian cradleboard. That is what most writers and artists have assumed Lewis was referring to with the word bier. But since she was captured by Hidatsas at about age 12, and passed through puberty among them, it is believed that Sacagawea was prepared for adulthood–and motherhood–according to Hidatsa ways. Therefore, most Hidatsa elders have long maintained she would have wrapped her baby in a shawl and carried him facing forward over one of her shoulders, as shown in the coin below, and in the statue of her on the Capitol grounds in Bismarck, North Dakota.

On 29 June 1805, having lost some of the field notes he wrote ten days earlier on his search for a portage route around the five falls of the Missouri River, Captain Clark set out to retrace his steps and fill in the blanks. York, Toussaint Charbonneau, and Sacagawea with her five-month-old boy, Jean Baptiste–later nicknamed “Pomp”–went along as sightseers. A sudden downpour drove them to shelter under some overhanging rocks in a deep, dry coulee, which suddenly became the conduit for a flash flood that nearly swept them all into the river just above the first, highest and deadliest of the five waterfalls.

With his typical nonchalance, Clark himself documented the most terrifying moment of all: “the woman lost her Childs Bear & Clothes bedding &c.” Lewis filled in the details:

the bier in which the woman carrys her child and all it’s cloaths wer swept away as they lay at her feet she having time only to grasp her child.

A footnote in the most recent edition of the Journals defines bier [and by inference, “bear”] as “the cradleboard in which Sacagawea carried her child on her back.”

Homonyms

Noah Webster, the father of American lexicography, who published his first dictionary in 1806, the year of the Expedition’s return, defined bier as “a wooden hand-carriage used for the dead.” In his American Dictionary of the English Language (1828), he traced this bier’s etymology to the Latin feretrum, from fero–”to carry.”

The latest Merriam-Webster’s takes the etymology of bier back to the 12th-century Middle English word bere, from Old English b[AE]r; akin to Old English beran, to carry, and similarly defines it as “a stand on which a corpse or coffin is placed.”

What’s more, the four-volume Dictionary of Arts and Science (sic) that the captains may have carried on the expedition defined bier as “A wooden machine for bodies of the dead to be buried.”[3]Published in London in 1753 (2nd ed., 1764), it was known as Owen’s Dictionary, after the publisher, John Owen.The full title is A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Science; comprehending … Continue reading Certainly that’s the kind of bier Charles Floyd‘s body might have been borne upon to its grave on the bluff.

None of the journalists, however, used the word in that sense. Lewis used bier eight times, invariably in that spelling. Clark used it three times, and John Ordway once, spelling it, in keeping with common practice, as they heard it: b-e-a-r, or b-e-a-r-e. But in every instance except the near-tragedy at the Falls, its meaning is established either contextually or by the insect’s identity (which Lewis always spelled musqueto).

This bier, then, is a bar or net serving to keep mosquitos from one’s personal blood supply, as in (see any recent Webster’s) “mosquito bar.” Lewis bought some “Muscatoe Curtains” and “8 ps. Cat Gut for Mosquito Curt” back in Philadelphia, and on 2 May 1804, sent sixteen “Musquitoe nets” from Saint Louis across the Mississippi to Clark at Camp Dubois. It seems probable that they were meant to supplement the supply he had purchased in Philadelphia, inasmuch as the Corps of Discovery had increased to twice the number originally planned for. In mid-June of 1804 Sergeant John Ordway tells us that Lewis gave the men “Musquitoes bears” to sleep in, and we know they all still had them on the 21 July 1805, when Lewis remarked that without their “musquitoe biers” his men couldn’t have gotten sufficient rest to do the work they faced. It appears that the captains didn’t buy any for the engagés, anticipating the Frenchmen would use their usual repellent, “voyageurs’ grease.” Correspondingly, the loss of the baby’s mosquito net would have been serious enough to warrant mention. Indeed, a year later, on the morning of 3 August 1806, William Clark remarked with concern and sympathy that “The Child of Shabono has been So much bitten by the Musquetor that his face is much puffed up & Swelled.” And no wonder! Jean Baptiste’s had been swept down the Missouri River more than a year before.

Confusion

Sacagawea Golden Dollar Coin

Obverse

© 2022 by WikiCommons user Tommy5544. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The Sacagawea on the dollar coin carries Pomp in a blanket, not on a “bier.”

Nicholas Biddle, the editor of the first published Lewis and Clark journals (1814), simply paraphrased Lewis: “The Indian woman had just time to grasp her child, before the net [italics added] in which it lay at her feet was carried down the current.” Biddle, of course, had talked about the incident with Clark.

Elliott Coues, in his 1893 edition of Biddle’s work, led his own readers astray by confusing two different words having two different roots.

This is an interesting use of the old word bier, which we found early in this work employed for a covering for the head to keep off mosquitoes (whence our mosquito-bar); but it is now archaic, except in connection with funerals. The “net” of the text therefore is simply the child’s cradle, made light and portable, something like a basket.[4]Elliott Coues, ed., History of the Expedition under the Command of Lewis and Clark . . . 1893. (Reprint, 3 vols. New York: Dover Publications, 1965), 2:395.

Nine years later Reuben Thwaites allowed that Coues might have been right, but cited an early 18th-century traveler’s use of a canvas sack as a baire against mosquitoes while on the lower Mississippi River, and wound up implying that baire and bier were synonyms.

The term baire, thus used, would readily spread, among the French voyageurs and traders, throughout the entire Northwestern region; and by the time of Lewis and Clark the canvas was, at least sometimes, replaced by gauze or net (as affording fresh air).[5]Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804≠1806 (8 vols., New York: Dodd, Mead, 1904-5), 2:197-98n.

The recent Dictionary of American Regional English confirms Thwaites’s conjecture. Four variants—bier, baire, bear, and bére—are linked to the Cajun word boire, and in turn to the French barre, meaning cross-bar, with each word denoting a “mosquito bar.” All were common in Louisiana in the late 18th century.[6]Frederic G. Cassidy, ed., Dictionary of American Regional English (3 vols. to date, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985–1996), s.v. bar.

Regrettably, the up-to-date Merriam-Webster’s compounds a century’s-worth of confusion in its opening definition of bier: “archaic: a framework for carrying.” Even the venerable Samuel Johnson, the 18th-century British father of modern English dictionaries, wasn’t that archaic; he specified the condition of the burden: “on which the dead are carried to the grave.”[7]Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: in which the Words are deduced from their Originals . . . (2 vols., London, 1755), s.v. bier.

The Shape

The only clue we have as to the construction of the biers the Corps of Discovery used is Biddle’s annotation to Lewis’s journal entry of 21 July 1805, perhaps gotten from William Clark or George Shannon: “made of duck or gauze, like a trunk—to get under.” Webster, in 1806, defined trunk as, among other less relevant things, “a long tube,” borrowing verbatim—as he did also for his definition of bier—from Entick’s New Spelling Dictionary of 1800.[8]John Entick’s New Spelling Dictionary, first published in London in 1764, and reprinted numerous times in this country (see Early American Imprints, First Series, No. 37375), was one of two … Continue reading

Elijah Criswell found one of the usages of the noun bear to denote a “pillow case.”[9]Elijah Harry Criswell, Lewis & Clark: Linguistic Pioneers (1940. Reprint, Bozeman, Montana: Headwaters Chapter of the Lewis & Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, 1991), “A Lewis and Clark … Continue reading Thus it is conceivable that a musqueto bier was a large sack made of gauze or netting, with a support such as a cross-bar to keep it away from the body.

The Sound

Clark and Ordway always spelled the noun denoting mosquito netting as “bear” or “beare,” evidently writing it as they heard it, and what they heard in Lewis’s Virginia accent didn’t rhyme with hear, or hair, but with bar. There’s ample evidence in the journals: On 5 August 1806, Clark wrote “I with one man went on the Sand bear and killed the Bear.”

Again, Criswell points out that Lewis referred to a sandbar as a “bear,” and thus probably pronounced it “bar.” Clark also, on 9 September 1806, called a sandbar a “bear,” which as a Kentuckian he might well have uttered as bar.[10]. . . as Daniel Boone is said to have spelled it in his legendary graffiti, having killed “a bar” on a certain tree in Kentucky.

Of course, pronunciations are difficult to convey in print, and we can only speculate about the sounds of the forms uncovered by DARE. In the 18th century, boire could have been spoken as bWAHr, BOYr, or BAR; bier as beeYAY or bir; baire as BAYr or BUYr; bère as BEHr; and bear, almost any of the above. Localisms are hard to account for, either in spelling or pronunciation, and they often trip up the stranger.

A spokesperson for the Lemhi Shoshone Indians, descendants of Sacajawea’s (sic) people, insists that Sacajawea (sic) carried her baby in a cradleboard. The Hidatsa Indians, among whom Sakakawea (sic) reached puberty and bore her child, contend she would have carried him as all Hidatsa mothers did, wrapped in a shawl or blanket draped over her shoulder. Nobody knows for sure, which she chose, or even whether she had a choice. But there can be little doubt that baby Jean Baptiste Charbonneau’s bier was a mosquito net, not a cradle board, much less a funeral litter.[11]Neither cradleboard nor cradle board appear anywhere in the Expedition’s journals, nor are they listed by Webster or Entick or any of their predecessors or contemporaries. Apparently the … Continue reading

What is still inconceivable is why no one—not his mother, nor Charbonneau, nor the captains, nor any of the men in the Corps of Discovery—gave little Pomp even a scrap of netting to shield him from the mosquitoes, after his own bier was lost in that flash flood at the Great Falls of the Missouri of July 1805.