Celilo Falls

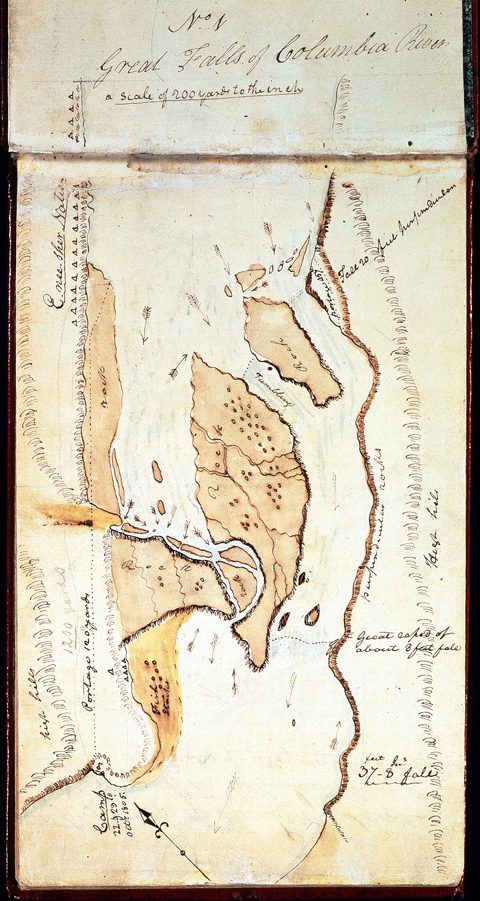

Clark’s Original Tinted Map

To see labels, point to the image.

American Philosophical Society, Codex H:1.

Clark made two nearly identical pen-and-ink drawings, with his sure and steady hand, of the Great Falls—or Celilo Falls—of the Columbia. This one appears in the notebook believed to have been his journal No. 6, now known as Codex H, which contains his daily entries from 11 October 1805 through 19 November 1805, as well as a number of other important documents.[1]For an inventory of the contents of Codex H, see Moulton, Journals, 2:558. This map begins on the flyleaf of the book and continues on page one. The page size is 7-7/8 by 4-7/8 inches.

Clark may have added the watercolor treatment during the ensuing winter at Fort Clatsop, or perhaps post-expedition, possibly with the expectation that it could serve as the basis for a hand-tinted engraving in the published version of the expedition’s journals.

A short distance downriver are the Short and Long Narrows, which Clark also charted for possible use in Nicholas Biddle‘s edition of the journals.

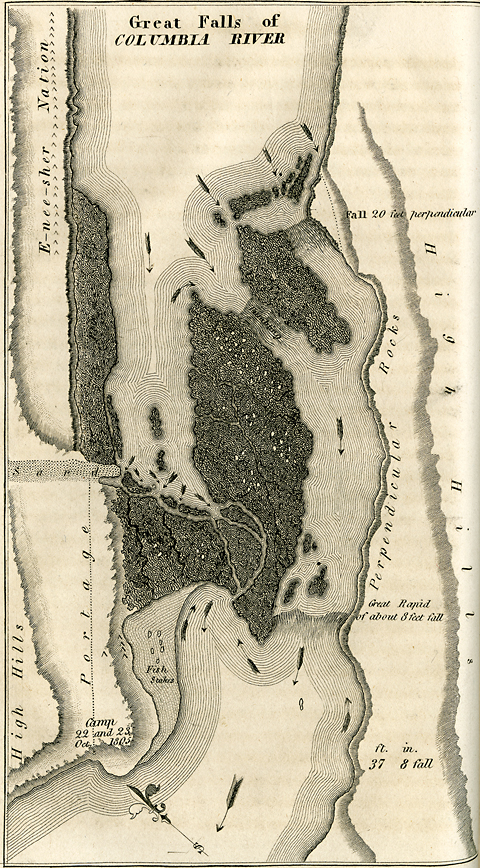

Clark’s 1814 Map (Detail)

To see labels, point to the image.

Phillips Collection, Mansfield Library Archives, The University of Montana, Missoul.a

From [Nicholas Biddle, editor,] History of an Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep, 1814), Volume 2, facing p. 31. Original size, 4-1/8 by 7-1/8 inches.

The text displayed above is from Biddle’s edition, Volume 2, pp. 31-32. The summary statement quoted at the bottom of the map does not appear in the journals, but was perhaps dictated to Biddle by either Clark or George Shannon during their conversations with him in 1810.

The arrows on the map indicate the direction of the current. Those that point upriver indicate major eddies where the Indians would have caught the most salmon. No doubt there were many more smaller eddies as well.

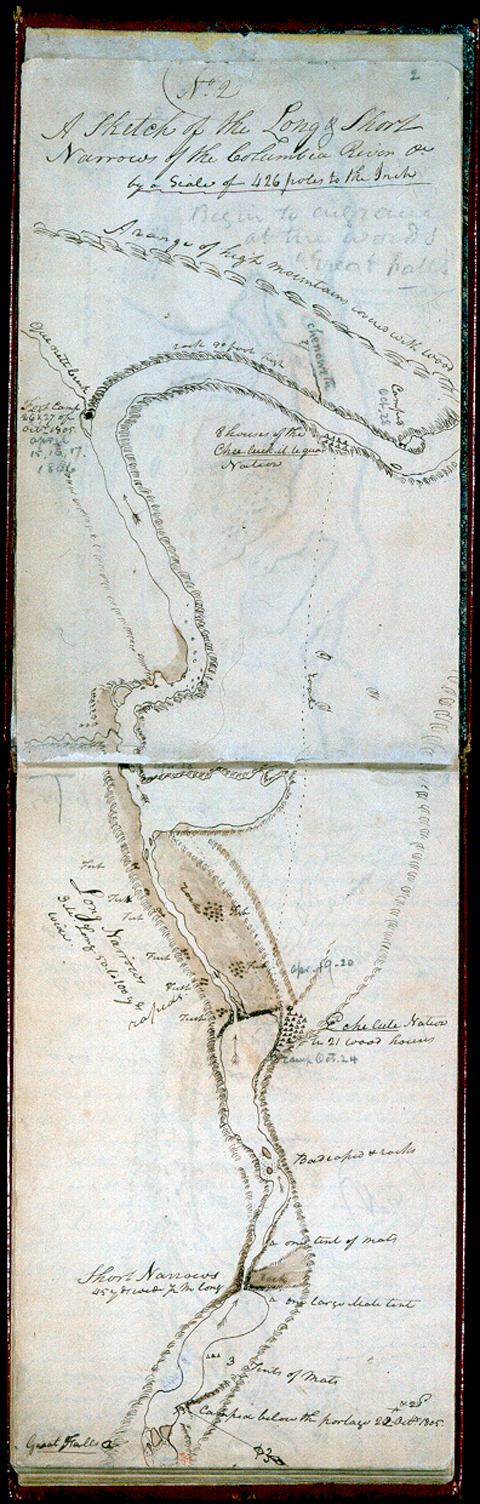

The Narrows

This sketch is on pages 2-3 of Codex H, Clark’s journal No. 6,[2]See Moulton, Journals, 5:330. which Nicholas Biddle deposited with the American Philosophical Society in 1818. The pencilled instruction to the engraver, which is barely legible at the top of the page, is in an unknown hand. It suggests that this was a sketch for the map in Voorhis No. 4, which is a slightly more detailed inversion of this one. Along with the partial application of brown watercolor, it also indicates that at one time this map, or its inversion, may have been considered for use as a hand-tinted engraving in the published version of the captains’ journals. That never happened. (The blue tint is a result of the aging of the paper, plus the bleed-through of ink from the maps on pages one and four.)

The name “Chenoweth” has been applied, possibly by Elliott Coues, to the creek Clark showed unnamed below Quenett Creek. Justin Chenoweth was a surveyor and school-teacher who arrived at The Dalles in 1849, and settled on land by the creek in 1852. Other details, mostly dates in an unknown hand shown here in parentheses, were added in pencil sometime after the pen-and-ink map was drawn.

Clark’s neat chart of the Short and Long Narrows would have been a boon to early 19th-century travelers, for Lewis and Clark’s own descriptions of the “obstacles” they encountered in the Columbia Gorge are somewhat difficult to grasp, and Biddle’s paraphrases were not much clearer. Elliott Coues, in his copiously annotated 1893 version of Biddle’s 1814 edition of the journals, recognized the need for elucidation. “Perhaps,” he wrote, “a few words serving as stepping-stones may help the reader to make the portage of these difficult places.”[3]Elliott Coues, ed., The History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 3 vols. (New York: Francis P. Harper, 1893), 2:940-41, note 1, The Columbian Cascades, and 2:954-56, note 1,The Dalles of the … Continue reading His solutions, which even accounted for recent engineering improvements at the Dalles and Cascades of the Columbia, were definitely helpful, even though Reuben Thwaites’s 1905 publication of the original journals soon re-introduced the original uncertaincies and confusions.

Today, except that the details of the expedition’s experiences convey a sense of the difficulty and the drama of their passages through the Gorge, all the issues are moot. From the foot of the old Cascades to the head of the old Celilo Falls, it’s all smooth sailing now.

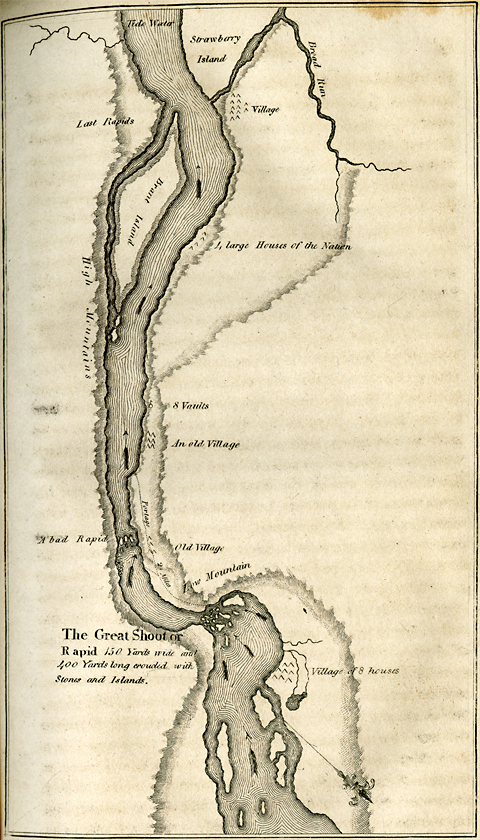

Cascades of the Columbia

This map is from History of an Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark, paraphrased by Nicholas Biddle, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep, 1814), volume 2, facing page 52. The size of the original engraving was 4 by 7 inches. Pertinent excerpts are quoted from Biddle’s text.

Clark’s “Great Shute [or Shoot]” is today’s Cascades of the Columbia River.[4]For fifty years after Lewis and Clark passed through the Gorge, relations between Indian residents and white travelers and settlers became increasingly strained. In 1855, Washington Territorial … Continue reading Returning on the snowmelt-swollen river in spring 1806, the men successfully pulled four of their five canoes up the falls with tow ropes, but the last one filled with water and pulled out of their grasp, to be carried away and lost downstream.

Lower Columbia

On 26 March 1806, the homeward-bound Corps of Discovery passed “an Elegant and extensive bottom on the South side [of the Columbia River] and an island near it’s upper point which we call Fanny’s Island and bottom.” Presumably Clark was thinking of his youngest sister, Frances. Topographically speaking, a “bottom” is a broad, flat river valley or floodplain, and the double-entendre in this context may have been unintentional. However, it evidently crossed his mind, and he had reservations about imposing any such sibling ribaldry upon the annals of the expedition. His second choice was “Fanny’s Valley & Isd.” The memorial to sister Fanny has not survived on current maps. In 1871 the island, a few miles downriver from Longview, Washington, was homesteaded by James F. Crim, and in 1927 officially became Crims Island.[5]Lewis A. McArthur, Oregon Geographic Names (6th ed., rev. and enl., Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1992).

“Sturgeon Island” was perhaps today’s Wallace Island.

The name of the “War ki a cum [Wahkiakum] Nation” came from a Chinookan expression meaning “region downriver.” The people of the “Skillute Nation” were properly called Watlalas. On New Year’s Eve, 1805, two canoes arrived at Fort Clatsop. One was from the War-ci-a-cum Village, with three Indians, and the other from “higher up the river of the Skil-lute nation” with three men and a woman.

Those people brought with them Some Wapto roots, mats made of flags[6]Common cat-tail, Typha latifolia L. & rushes, dried fish and Some fiew She-ne-tock-we (or black) roots & Dressed Elk Skins, all of which they asked enormous prices for, particularly the Dressed Elk Skins; I purchase of those people Some Wapto roots, two mats and a Small pouch of Tobacco of their own manufactory–for which I gave large fish hooks, which they were verry fond.

The “Cow-a-lis-kee River” is today the Cowlitz River, with the cities of Longview and Kelso, Washington at its confluence with the Columbia River. A Hudson’s Bay Co. warehouse was built at the mouth of the Cowlitz in 1846, and an American settlement called Monticello flourished there from 1852 until 1867. In 1923 a lumber mill became the center of Longview, the first planned city in the Northwest. The name Cowlitz—which over the years has been spelled 16 different ways—possibly came from the Salishan word tawallitch, meaning “capturing the medicine spirit.”[7]James W. Phillips, Washington State Place Names (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1971).

“Those Indians,” Clark said of the “Cath lah mah” [Kathlamet] Nation, “are Certainly the best canoe navigators I ever Saw.” (11 November 1805)

“Sea Otter Isd.” had already been named Puget Island, for Lieutenant Peter Puget, a member of Captain George Vancouver’s crew, in 1792.

Station Camp

Although this map is labled “ca. November 16-25” in Moulton (6:52), Clark probably drew it sometime during the winter of 1806 from the field notes he made in November (see Moulton, Atlas, Maps 90-93). For one thing, the almost incessant rain and wind they endured from the time they left Station Camp until the captains moved into their quarters at Fort Clatsop on 23 December 1805 would have prevented Clark from preparing such a detailed chart. Moreover, “Point William” (today, Tongue Point) did not acquire that name until 27 November 1805 (Moulton, 6:90). His “Point Lewis” is now Smith Point, at the west end of Astoria, Oregon, and slightly east of the mouth of Youngs Bay. “Point Distress” is now Point Ellice, Washington. The distance from Station Camp to Cape Disappointment would actually have been 6.9 miles, not 11; his 7-mile estimate of the distance to Point Adams would have been more accurately 3.8 miles.

–Robert N. Bergantino

From Station Camp Observations

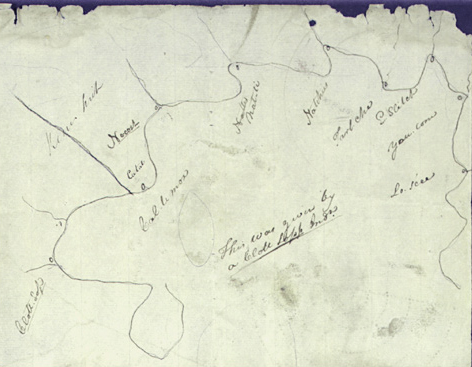

Map from Clatsop Information

This map was drawn by, or with the assistance of, an unidentified Clatsop Indian early in January 1806. If we only had some record of the conversation that was carried on between Clark and his informant, we might be able to make sense of it, but it bears no resemblance to any other map from that time to this. Nevertheless, it is another piece of the material evidence of many Indians’ willingness to help the visiting Americans.

Clark has written the phonetic equivalents of the names of the Indian tribes as he heard them. Few are of any significance today, nor for the overall story of the expedition’s visit to the lower Columbia River. The only names that were used elsewhere in the extant journals are “Clott Sop” (Clatsop), “Cal-le-moX” (Tillamook) and “Nat-ti.”

Notes

| ↑1 | For an inventory of the contents of Codex H, see Moulton, Journals, 2:558. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See Moulton, Journals, 5:330. |

| ↑3 | Elliott Coues, ed., The History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 3 vols. (New York: Francis P. Harper, 1893), 2:940-41, note 1, The Columbian Cascades, and 2:954-56, note 1,The Dalles of the Columbia. |

| ↑4 | For fifty years after Lewis and Clark passed through the Gorge, relations between Indian residents and white travelers and settlers became increasingly strained. In 1855, Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens consummated a treaty between the U.S. and the Yakamas, Klickitats, Wishhams, Wascos, and other Cascades tribes, which required them all to move to a reservation within one year, but allowed white citizens to claim thereafter any land on the reservation that the Indians had not placed under cultivation. The Indians, however, were allowed to retain their traditional fishing, hunting, and gathering rights. In March 1856, the tribes banded together under Yakama Chief Kamiakin, who had conceived a plan to retake control of the portage at the Cascades. Kamiakin and his forces attacked two American steamers above the rapids, burned some buildings near Fort Rains on the Middle Cascades, and attacked the fort’s blockhouse where some 40 men, women, and children had taken refuge. On the next day, 27 March, 40 mounted infantrymen arrived from the Dalles, followed by a larger force under Lieutenant Steptoe. The Yakamas fled, leaving the Cascade bands, who surrendered. The whites, having suffered six fatalities, called the incident “The Cascade Massacre.” In retribution, Steptoe hanged nine of the captured Indians. Stevens left the governorship in 1857 after being elected as the territory’s delegate to Congress. |

| ↑5 | Lewis A. McArthur, Oregon Geographic Names (6th ed., rev. and enl., Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1992). |

| ↑6 | Common cat-tail, Typha latifolia L. |

| ↑7 | James W. Phillips, Washington State Place Names (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1971). |