Scientific Name

The botanical designation for this storied miniature shrub is Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng.[1]The bearberry’s Latin name is pronounced arc-toe-STAFF-ee-los oo-va ER-see. The initial L. stands for Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778). Spreng. stands for Curt Polykarp Joachim Sprengel … Continue reading Arktos is Greek for “bear,” and staphyle is Greek for “a bunch of berries.” Just for good measure, uva-ursi, the designation for the species, also means “berry-of-bear,” Uva-ursi being an early generic name that was rejected by the Swedish naturalist, Carl Linnaeus when he established the principles and procedures of modern botanical nomenclature in 1753. His role in the taxonomy of the bearberry is acknowledged by the parenthetical /L./ in the plant’s full name. “Spreng.” stands for the German botanist Curt Polycarp Joachim Springel (1766-1833), who wrote the first full description of the plant.

Bearberry

Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng

© 2007 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Common Names

One of the commonest of its common names in North America is the Algonquian (Delaware) word kinnikinnick, meaning “mixture.” Equally familiar in various parts of its English-speaking habitats is bearberry, which first appeared in print around 1625. But it also has borne a long lexicon of other names: bear’s bilberry, bear’s grape, raisin d’ours in France. Bear’s weed, chokerberry, chipmunk’s apple, creashak, crowberry, devil’s tobacco, Indian tobacco, hog cranberry, larb, manzanita, mealberry, mealy-plum vine, mountain box, mountain cranberry, mountain laurel, rapper-dandies, redberry, rockberry, sandberry, universe vine, upland cranberry, uvursy, whortleberry, and wild cranberry.[2]Dictionary of American Regional English (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1985– ), s.v. bearberry. CRC World Dictionary of Plant Names (4 vols., New York: CRC Press, … Continue reading Herbalists know it best as uva-ursi. Lewis and Clark sometimes called it kinnikinnick, sometimes sacacommis.

Meriwether Lewis heard in the latter name an intimation of a faintly plausible but quite erroneous etymology–”from the circumstance of the Clerks of those trading companies carrying the leaves of this plant in a small bag for the purpose of smokeing.” But saccacomis–or sac • comis, sagakomi, segockimac, or segockiniac–were all derived from a Chippewa Indian word for “mixture,” the variant spellings, including Clark’s Sackacome, representing different journalists’ transliterations of the local pronunciations they heard. The Blackfeet Indian name for bearberry is kakahsiin; the Salish call the berries skw lsé. The Pawnee name for the whole plant is nakasis, meaning “little tree.”[3]Melvin R. Gilmore, Uses of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region (1914; enlarged ed., Lincoln: University of Nebraska press, 1977), 56. (For a description of the smoking mixtures described in the journals, see Smoking.)

Lewis’s Description

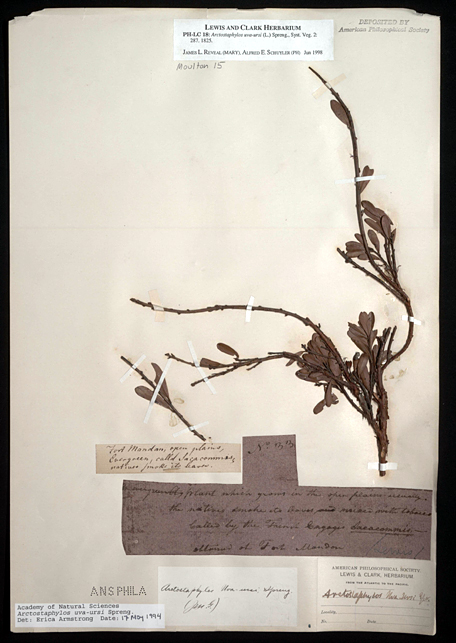

Lewis’s Herbarium Specimen

To read the labels, point to the image.

Courtesy Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia

Lewis’s bearberry is his specimen No. 33. The label in his handwriting reads “an evergreen plant which grows usually in the open plains, the natives smoke its leaves mixed with Tobacco; called by the French engagés Sacacommé.[4]Moulton, 3:464. James L. Reveal, Gary E. Moulton, and Alfred E. Schuyler, “The Lewis and Clark collections of vascular plants: Names, types and comments,” Proceedings of the Academy of … Continue reading Since the species does not occur anywhere near Fort Mandan, it is possible that it was collected elsewhere by one of the Mandans and given to Lewis at the fort. Otherwise, it may have been part of the material sent to Lewis by Hugh Heney. Lewis sent it back east on the barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) in the spring of 1805. It is now in the Lewis and Clark Herbarium, at the Academy of Natural Sciences, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. See also Lewis’s Plant Collection.

At Fort Clatsop on 29 January 1806, drawing partly on the Canadians’ information at Fort Mandan, partly on his observations along the route, and finally upon the ample supply of specimens nearby, he described the plant as follows. (To see definitions and explanatory notes, point to any double-underline word or phrase.) It was, he said:

the growth of high dry situations, and invariably in a piney country or on it’s borders. It is generally found in the open piney woodland as on the Western side of the Rocky mountains, but in this neighbourhood we find it only in the prairies or on their borders in the more open wood lands.[5]Bearberry is rather common throughout the Northern Hemisphere in Eurasia and North America. It occurs in the mountains of the American West as far south as New Mexico. In northern Canada and Alaska … Continue reading A very rich soil is not absolutely necessary, as a meager one frequently produces it abundantly.

The natives on this [the west] side of the Rocky mountains who can procure this berry invariably use it. To me it is a very tasteless and insippid fruit.

This shrub is an evergreen. The leaves retain their verdure most perfectly through the winter, even in the most rigid climate, as on lake Winnipic.[6]At Fort Mandan on 28 February 1805, the captains received a gift of “Sacka comah” from Hugh Heney, a trader with the North West Company stationed at Fort Assiniboine, southwest of Lake … Continue reading

The root of this shrub puts forth a great number of stems which separate near the surface of the ground, each stem from the size of a small quill to that of a man’s finger. These are much more branched, the branches forming an acute angle with the stem, and all more properly procumbent than creeping, for altho’ it sometimes puts forth radicles from the stem and branches which strike obliquely into the ground, these radicles are by no means general, nor equable in their distances from each other, nor do they appear to be calculated to furnish nutriment to the plant but rather to hold the stem or branch in its place.

The bark is formed of several thin layers of a smooth, thin, brittle substance of a dark or redish brown color, easily separated from the woody stem in flakes.The leaves with rispect to their position are scattered yet closely arranged near the extremities of the twigs particularly. The leaf is about ¾ of an inch in length and about half that in width, is oval but obtusely pointed, absolutely entire, thick, smooth, firm, a deep green and slightly grooved. The leaf is supported by a small footstalk of proportionable length.

The berry is attached in an irregular and scattered manner to the small boughs among the leaves, though frequently closely arranged, but always supported by separate short and small peduncles, the insertion of which produces a slight concavity in the bury while it’s opposite side is slightly convex. The form of the berry is a spheroid, the shorter diameter being in a line with the peduncle.—This berry is apericarp, the outer coat of which is a thin, firm, tough pellicle.[7]Consistent with botanical usage in his day, Lewis used pericarp to denote a fruit. Today, the word is applied to the wall of a ripened ovary; the fruit of the bearberry is simply called a berry. … Continue reading The inner part consists of a dry mealy powder of a yellowish white color enveloping from four to six proportionably large, hard, light brown seeds, each in the form of a section of a spheroid, which figure they form when united, and are destitute of any membranous covering. The color of this [ripened] fruit is a fine scarlet.

The natives usually eat them without any preparation. The fruit ripens in September and remains on the bushes all winter. The frost appears to take no effect on it. These berries are sometimes gathered and hung in their lodges in bags where they dry without further trouble, for in their most succulent state they appear to be almost as dry as flour.—

Food Source

Bearberry Blooms

© 2008 by Walter Siegmund. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.

At Fort Clatsop, on 25 January 1806, Lewis noticed that the fruits and berries eaten by the Indians of that vicinity included “a Scarlet berry about the Size of a Small Cherry,” referring to the bearberry. The berries once served as a staple food for Native Americans as well as white settlers. Indians, it is said, cooked them in salmon oil, bear fat or fish eggs, or added them to soups and stews. Boiled, they were sometimes mixed with snow for a wintertime treat.[8]Linda Kershaw, Edible & Medicinal Plants of the Rockies (Renton, Washington: Lone Pine Publishing, 2000), 90–91. Important: Experimentation and/or self-medication with wild foods and medicines, … Continue reading Lewis himself, evidently having sampled one, judged it “a very tasteless and insippid fruit,” but added that It was reported to taste sweeter after boiling.

Indeed, a fruit so seductively colored, and set off against such a salubrious deep green foliage, ought to taste as good as it looks. Generally speaking, it doesn’t. About those pretty berries Lewis was right the first time, although as to the leaves, when dried, crushed, and mixed with tobacco, they added “an agreeable flavor.

On the other hand, black bears, rodents, songbirds and turkeys evidently find the bright berries tasy. Blue grouse (Dendragapus obscurus, “tree-loving, inconspicuous”) and spruce or Franklin’s grouse (Canachites canadensis, “noisemaker, of Canada”) seem especially fond of them.[9]John J. Craighead, Frank C. Craighead, Jr., and Ray J. Davis, A Field Guide to Rocky Mountain Wildflowers (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1963), p. 130. Deer and mountain sheep eat the leaves during fall and winter.

Blooms Noticed

On 11 April 1806, en route back up the Columbia River, the captains remarked that the “Sackacommis” was in bloom. That was at the Cascades of the Columbia, about 200 feet above sea level. They may also have seen the plant in the Bitterroot Mountains several thousand feet up, but in any case they didn’t mention the plant’s pretty little pale-pink, waxy, urn-shaped flowers. One would like to have read another of Lewis’s characteristically pithy descriptions.

Medicine

The leaves of the bearberry, which contain two glucosides plus tannic and gallic acid, have been strong medicine since at least the thirteenth century, and perhaps long before that. They once were used for their potent astringent and diuretic effects, and are still employed by some herbalists, although with rigorous limitations.

The leaves are sometimes used in the tanning of hides.[10]Ibid.

Holiday decorations

In Euro-American culture, bearberry foliage often serves as a Christmas decoration.

Important: The ingestion of some plants can be harmful or even fatal. Experimentation and/or self-medication with wild foods and medicines without advice from a physician or other qualified authority can be dangerous, and therefore is not recommended.

Notes

| ↑1 | The bearberry’s Latin name is pronounced arc-toe-STAFF-ee-los oo-va ER-see. The initial L. stands for Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778). Spreng. stands for Curt Polykarp Joachim Sprengel (1766–1833), a German professor of medicine and botany. Red osier dogwood is Cornus sericea. Cornus is the Latin name for the cornelian cherry; sericea means silky and refers to the pubescence of the leaves. In the older American literature, this dogwood was also known as Cornus stolonifera. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Dictionary of American Regional English (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1985– ), s.v. bearberry. CRC World Dictionary of Plant Names (4 vols., New York: CRC Press, 2000), 1:187. |

| ↑3 | Melvin R. Gilmore, Uses of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region (1914; enlarged ed., Lincoln: University of Nebraska press, 1977), 56. |

| ↑4 | Moulton, 3:464. James L. Reveal, Gary E. Moulton, and Alfred E. Schuyler, “The Lewis and Clark collections of vascular plants: Names, types and comments,” Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 149 (January 1999): 9. |

| ↑5 | Bearberry is rather common throughout the Northern Hemisphere in Eurasia and North America. It occurs in the mountains of the American West as far south as New Mexico. In northern Canada and Alaska it may be found at or near sea level. The plant is often seen in cultivation as an ornamental ground cover. |

| ↑6 | At Fort Mandan on 28 February 1805, the captains received a gift of “Sacka comah” from Hugh Heney, a trader with the North West Company stationed at Fort Assiniboine, southwest of Lake Winnipeg in today’s Manitoba, Canada. |

| ↑7 | Consistent with botanical usage in his day, Lewis used pericarp to denote a fruit. Today, the word is applied to the wall of a ripened ovary; the fruit of the bearberry is simply called a berry. Pellicle (PELL-i-kul) is Latin for skin, here the outer layer or skin of the fruit. |

| ↑8 | Linda Kershaw, Edible & Medicinal Plants of the Rockies (Renton, Washington: Lone Pine Publishing, 2000), 90–91. Important: Experimentation and/or self-medication with wild foods and medicines, without advice from a physician or other qualified authority, is not recommended. The ingestion of some plants can be harmful or even fatal. |

| ↑9 | John J. Craighead, Frank C. Craighead, Jr., and Ray J. Davis, A Field Guide to Rocky Mountain Wildflowers (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1963), p. 130. |

| ↑10 | Ibid. |