Fearing failure to reach their objectives, the captains conceived of a bold diplomatic plan. The plan would place them at great risk.

Portents

Near Mobridge, South Dakota

© 2011 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

By the time they left Fort Mandan on 7 April 1805, they had filled in many of the blanks in the map that Albert Gallatin had hired Nicholas King to assemble especially for them, from the latest information about the Northwest. Or they believed they had. But there were steadily darkening portents of uncertainty, confusion and disappointment on the horizon. First was the elusive “River that Scolds All Others,” then the mystery at the Marias, the one-become-five falls of the Missouri, and the long anxiety over when, or even whether, they would find Sacagawea‘s people. The slow, silent crumbling of the theory that the “Shining Mountains” would prove to be narrow and low, climaxed by that shocking and surely unforgettable moment when Lewis first peered over the ridge dividing the Missouri from the Columbia. And then the Indians’ “best” road across the Bitterroots, “those tremendious Mountanes,” would be the expedition’s worst road of all.

Finally, there was that long, day-by-day disintegration of the centuries-old vision of a riverine Passage Through the Garden: There wasn’t any. By mid-July 1806 the transmountain portage would prove to be 340 tortuous miles long . . . by the shortest way. Never mind the hairbreadth escapes from death or disaster; the cold, hunger and illness; or any of the countless other tests of human endurance. Or the embarrassment of “the experiment”—Lewis’s portable iron-framed boat. Or the intimidations and hostilities of some powerful and numerous Indians on the Missouri and the Columbia. The very land they had come to explore and claim seemed to be against them.

Jefferson’s Embarrassment

From the outset Lewis had the best interests of his friend, mentor and commander-in-chief at heart. At Cincinnati, on his way down the Ohio in the fall of 1803—still expecting to spend the coming winter somewhere up the lower Missouri—he had written to Jefferson of his concerns, and his own plan of action.

As this session of Congress has commenced earlyer than usual, and as from a variety of incidental circumstances my progress has been unexpectedly delayed, and feeling as I do in the most anxious manner a wish to keep them in a good humour on the subject of the expedicion in which I am engaged, I have concluded to make a tour this winter on horseback of some hundred miles through the most interesting portion of the country adjoining my winter establishment.

He was thinking of looking around in the direction of Santa Fe, the trade center in New Spain that beckoned more men, perhaps, than the beaver lodges of the Northwest. He would even send his co-captain off in another direction, confident that the two of them would gain valuable information “which, if it dose not produce a conviction of the utility of this project, will at least procure the further toleration of the expedition.”[1]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with Related Documents, 1783–1854 (2nd ed., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:131.

The President had fired back a decisively negative but confidently reassuring reply: “you must not undertake the winter excursion which you propose.” It would be more dangerous that the assigned route, “& would, by an accident to you, hazard our main object, which, since the acquisition of Louisiana, interests everybody in the highest degree.” Furthermore, he considered the expedition double-manned, and thus more assured of success, “for which reason neither of you should be exposed to risques by going off of your line.” Besides, he had added, it seemed certain that Congress would approve his plan to send expeditions up other rivers of the Missouri and Mississippi, to establish points “in the contour of our new limits.” He restated his original directive: “The object of your mission is single, the direct water communication from sea to sea formed by the bed of the Missouri & perhaps the Oregon.”[2]Ibid., 137.

But by 20 September 1805, when they arrived at Weippe Prairie on the west slope of the Bitterroot Mountains, Lewis and Clark had consummated their most significant discovery of all, that the president’s overriding premise had been wrong, and so his rationale for the entire expedition was inherently flawed. There was no Northwest Passage by water; and the portage they found took much longer than a day. The political repercussions from that alone could be immensely embarrassing to Jefferson.

Something had to be done.

Bold Plan

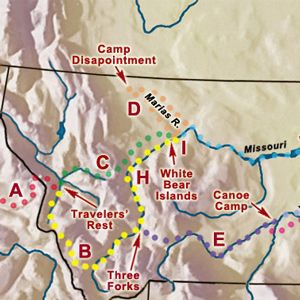

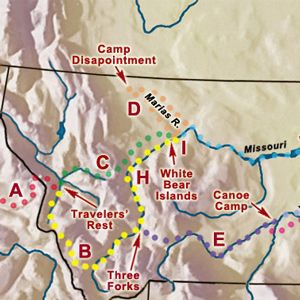

It was the boldest, most complicated, and most hazardous plan of all. Conceived at Fort Clatsop,[3]Even then, in February 1806, President Jefferson was reporting to Congress on the course of the expedition, and reminding its members that Lewis’s objective was to cross the “highlands by … Continue reading finalized at Travelers’ Rest, and set in motion early in the morning of July 3, 1806, it might have eclipsed even a discovery that there really was a Passage through the Garden of the West, had any part of it succeeded. And if all had succeeded, the expedition and its two leaders might have been showered with glory in their own time to a degree not even equaled by that which we shower upon their memories after two hundred years have elapsed.

But although facile games of “what if?” often are entertaining, they seldom teach us what really happened. Instead, let us look closely at the elements of the captains’ plan, and the related events that actually ensued, for they reflect Jefferson’s policies toward Indian nations.

The captains’ scheme was grounded in a decision that defied their commander-in-chief’s orders—and for which they might well have been court-martialed: They would not only divide their unit into two contingents, but ultimately into five widely separated, equally indefensible details. It placed the entire expedition at risk of disaster.

Lewis’s Shortcut

Captain Lewis would try out the shortcut from Travelers’ Rest to the Great Falls of the Missouri via the Blackfoot River, which Indians had mentioned to the captains several times.[4]In a letter he wrote to President Jefferson from Fort Mandan in April 1805, he advised, “On our return we shal probably pass down the yellow stone river, which from Indian information, waters … Continue reading Then he and three of his men would proceed up Maria’s River to ascertain whether its sources lay at or above fifty degrees north latitude, information that could establish a clear geographical delineation of Louisiana’s northern boundary. The story of his journey on the Marias River and in the heart of Blackfeet Indian country, its one big disappointment, and its long-term tragic consequences, is well known. Had it worked out as Lewis hoped, it might have simplified U.S.-British relations for at least the next decade—until the international boundary was amicably defined, in large part, after the War of 1812.

Clark on the Yellowstone

Second, Captain Clark would return to the Three Forks of the Missouri via Camp Fortunate, and send Sergeant Ordway with eleven men in the canoes back to the Great Falls. He, with nine men and forty-nine horses, plus York, Sacagawea and her child, would then proceed overland to the Yellowstone River, build dugout canoes, and meet Lewis and his Missouri River contingent at the confluence of the two rivers around the first of August. (They almost made it on schedule, and that was perhaps the best outcome of all.)[5]Clark arrived at the mouth of the Yellowstone at 8:00 on the morning of the third, but mosquitoes drove him on down the Missouri; Lewis caught up with him at noon on 12 August 1806, about 130 miles … Continue reading

It would have been a bonus had Clark also learned enough about the geography of the Yellowstone River to prove that this “delightfull river” arose near the “North river” (the Rio Grande) in Spanish America. Rumor and conjecture led Lewis and Clark to theorize that the Yellowstone “also most probably has it’s westerly sources connected with [those of] the Multnomah [today, the Willamette] and . . . the main Southerly branch of Lewis’s river [the Snake], while it’s Easterly branches head with those of Clark’s R. [the Clark’s Fork of the Yellowstone], the Bighorn and River Platte, and may be said to water the middle portion of the Rocky Mountains from N W to S. E. for several hundred miles.” But Clark didn’t get to see the Yellowstone above the Big Bend, nor did he meet any Crow Indians who might have shared their knowledge of what its upper reaches were really like, so these “facts” added up to hearsay spiced with guesswork, and their theory was still just a bird in the bush.[6]The theory is in Clark’s journal entry for August 3, 1806, but it’s in Lewis’s hand. Since Lewis didn’t catch up with Clark until August 12, they must have discussed the … Continue reading

Each party also had to retrieve the precious supplies that had been cached at Camp Fortunate, White Bear Islands, and the mouth of the Marias—which clearly suggests this whole scheme was nascent before the Corps left the Marias in June 1805.

Siouan Entreaty

The boldest plan of all, however, was basically consistent with the President’s instruction to Lewis: “If a few of their influential chiefs, within practicable distance, wish to visit us, arrange such a visit with them . . . at the public expense.[7]Jackson, Letters, 1:64. The most influential would be the chiefs of the Sioux, who controlled the conduit to the existing and potential trading centers on the upper Missouri River, and they were certainly within practicable distance. If this plan succeeded, the chiefs would be impressed by American strength and wealth, would go home and persuade their people and their neighbors to live in peace, renounce their old British loyalties, welcome American trading posts up and down the Missouri, and become full-fledged partners in the grand enterprise of extending the American nation all the way to the Pacific Coast.

The leading figure in this scenario was a Canadian fur trader named Hugh Heney.

Hugh Heney, Key Figure

Hugh Heney had been an innkeeper in Montreal before becoming a free trader in 1800. In 1804 he joined the North West Company, a bitter rival of the long-established Hudson’s Bay Company.[8]The Hudson’s Bay Company was organized in England in 1670, not only to carry on fur trading with Indians in the territory surrounding Hudson Bay, but also to search for the legendary Northwest … Continue reading As a free trader he had established a positive relationship with the Sioux Indians who were, according to Clark, “Visious,” but had “behaved tolerably well to the only trader Mr. Haney.”[9]“Estimate of the Eastern Indians,” in Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (13 vols., Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001), 3:417. The … Continue reading Stationed at the North West Company’s Fort Assiniboine, near the mouth of the Souris (Mouse) River, Heney, whom Lewis characterized as “a gentleman of rispectability,” made two trips to the Knife River Villages during the winter of 1804–5, and shared a considerable amount and variety of information with the American captains. Moreover, Heney had expressed his willingness to help their government in dealing with the Indians he knew best—perhaps seeing this as a way of subverting the HBC’s power among the Indians in that part of the continent.[10]Their conversations must have been wide-ranging, for Heney also sent two messengers on a 300-mile round trip from Fort Assiniboine to deliver a specimen of “a plant common to the praries in … Continue reading Although Lewis and Clark had nothing particular to suggest at that time, they kept his offer in mind.

Sometime before the Corps of Discovery’s arrival back at Travelers’ Rest at the end of June 1806, the captains composed a long letter to Heney, reminding him of his offer and appealing to his personal interests as well as those of the United States. They asked if he would try to persuade “the most influensial Chiefs” of the Teton, Sisseton and Yankton Sioux, to visit President Jefferson, and himself escort them back to Washington, D.C., preferably in company with the returning Corps. They especially wanted Teton Sioux chiefs included, because their people would “always prove a serious inconveniance” to fur traders aiming for the upper Missouri or the Yellowstone.

Lewis and Clark were confident that the Indians would gain:

an ample view of our population and resourses, become convinced themselves, and on their return convince their nations of the futility of an attempt to oppose the will of our government, particularly when they shall find, that their acquiescence will be productive of greater advantages to their nation than their most sanguine hopes could lead them to expect from oppersition.[11]Ibid., 1:308.

The captains assured Heney that their country’s intentions would always be friendly in nature, but that she would not tolerate interference with her citizens’ commercial traffic up and down the Missouri River by “a fiew comparitively feeble bands of Savages who may be so illy advised as to refuse her proffered friendship.” They acknowledged that the Sioux Indians’ “long established prejudices in favour of the Traders of the river St. Peters will probably prove a serious bar to your present negociations,” unless the government had already taken action on the report he had submitted in April 1805.[12]The “traders of the river St. Peters” was a reference principally to Murdoch Cameron, whose post was situated in the very heart of Sioux country, on the river now known as the Minnesota. … Continue reading In any case, they said, the Indians should be informed that the United States now controlled all the tributaries of the Missouri, and could prevent them from dealing with their “accustomed traders.”

Heney’s personal fortunes would be enhanced, too. He would earn one dollar per day for the duration of his own expedition to the East Coast and back, a fairly generous offer, considering a private’s pay was five dollars per month, and a captain’s $40. The captains would give him enough horses for his purposes, and assure him an allowance of $200 for Indian gifts to use in bargaining with the chiefs. Finally, Lewis would recommend him for an appointment as Indian agent at a projected trading post near the mouth of the Cheyenne River, at a salary of $75 per month, plus a daily subsistence allowance of $1.20 per day.

The linchpin in the captains’ plan to graft Heney into the future of American trade on the upper Missouri was Pryor’s Mission.

Reviewed in part by Prof. Albert Furtwangler

The Rest of the Story

On the Road to the Buffalo

Weippe to White Bear Islands

After splitting up at Travelers’ Rest, Lewis took a shortcut back to the Great Falls of the Missouri and then explored the upper Marias River.

Dividing into as many as five separate details was part of a bold, diplomatic plan to achieve three of the objectives set by President Jefferson.

Clark on the Yellowstone

Travelers' Rest to North Dakota

Clark leads a large group from Travelers’ Rest to the Beaverhead River where supplies and canoes are cached. Ordway takes the canoes to the Falls of the Missouri and Clark’s group paddles the Yellowstone in two small canoes lashed together. Pryor’s group must use bull boats after all the horses are stolen by Crows.

Lewis on the Marias

Cut Bank Creek to North Dakota

With only three others, Lewis continues his June 1805 exploration of the Marias River hoping to find its source north of the 50th parallel. They find that it flows south of the 49th. Heading back, they come across a small group of young Blackfeet, and the encounter turns fatal. Both groups flee.

July 20, 1806

Hopes dim and rise

Lewis sees the Marias watershed and hopes for extending the Louisiana Territory dim. Clark builds dugouts on the Yellowstone and hopes Hugh Heney will accept a commission. Ordway and Gass are at the Falls of the Missouri.

Pryor’s Mission

“You will take the horses which we have brought with us to the Mandans Village on the Missouri….you will hire a pilot to conduct you and proceed on to those establishments and deliver Mr. Heney the letter which is directed to him.”

Did they take on too much risk when they split into small groups on the way home? Did the Lewis and Clark Expedition actually fail?

Notes

| ↑1 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with Related Documents, 1783–1854 (2nd ed., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:131. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ibid., 137. |

| ↑3 | Even then, in February 1806, President Jefferson was reporting to Congress on the course of the expedition, and reminding its members that Lewis’s objective was to cross the “highlands by the shortest portage, to seek the best water communication thence to the Pacific ocean.” Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783–1854 (2nd ed., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:299. |

| ↑4 | In a letter he wrote to President Jefferson from Fort Mandan in April 1805, he advised, “On our return we shal probably pass down the yellow stone river, which from Indian information, waters one of the fairest portions of this continent.” Yet they would leave one pirogue and a cache of supplies at the mouth of the Marias River, and the other pirogue and two caches at the Great Falls, which indicates that the information gained from Indians the previous winter had set the captains to thinking about splitting the Corps of Discovery into two contingents on their return trip. Ibid., 1:234. |

| ↑5 | Clark arrived at the mouth of the Yellowstone at 8:00 on the morning of the third, but mosquitoes drove him on down the Missouri; Lewis caught up with him at noon on 12 August 1806, about 130 miles downriver. |

| ↑6 | The theory is in Clark’s journal entry for August 3, 1806, but it’s in Lewis’s hand. Since Lewis didn’t catch up with Clark until August 12, they must have discussed the probabilities before Lewis inserted their conclusions in Clark’s journal. Moulton, Journals, 8:277. See also John L Allen, Lewis and Clark and the Image of the American Northwest (New York: Dover, 1975), 359–62. “The Indians”—probably the Hidatsas—also told them that “a good road passes up this river to it’s extreem source from whence it is but a short distance to the Spanish settlements,” and further related that there was “a considerable fall” on the upper Yellowstone, in the mountains. The second point is a fact, while the first is an exaggeration: It’s more than 600 miles—perhaps three weeks’ travel—from the headwaters of the Yellowstone to Santa Fe. |

| ↑7 | Jackson, Letters, 1:64. |

| ↑8 | The Hudson’s Bay Company was organized in England in 1670, not only to carry on fur trading with Indians in the territory surrounding Hudson Bay, but also to search for the legendary Northwest Passage to the Pacific. |

| ↑9 | “Estimate of the Eastern Indians,” in Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (13 vols., Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001), 3:417. The captains also engaged Pierre Dorion, Sr. |

| ↑10 | Their conversations must have been wide-ranging, for Heney also sent two messengers on a 300-mile round trip from Fort Assiniboine to deliver a specimen of “a plant common to the praries in this quarter,” the root of which he claimed to have used successfully in the treatment of “the bite of the made wolf or dog and also for the bit of the rattle snake.” The plant has not been positively identified, and the specimen, which Lewis sent to Jefferson along with a few pounds of the root, has never been found. Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783–1854 (2nd ed., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:220. |

| ↑11 | Ibid., 1:308. |

| ↑12 | The “traders of the river St. Peters” was a reference principally to Murdoch Cameron, whose post was situated in the very heart of Sioux country, on the river now known as the Minnesota. In his “Estimate of the Eastern Indians” Lewis warned Jefferson that the Sioux were “the vilest miscreants of the savage race, and must ever remain the pirates of the Missouri, until such measures are pursued, by our government, as will make them feel a dependence on its will for their supply of merchandise. Unless these people are reduced to order, by coercive measures, I am ready to pronounce that the citizens of the United States can never enjoy but partially the advantages which the Missouri presents.” Gary E. Moulton, The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition (13 vols., Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001), 3:418. |