Travelers’ Rest to the Three Forks

Big Hole Valley

© 25 July 2011 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

On 3 July 1806, at Travelers’ Rest, the captains divided the Corps into two units. Clark would lead his men on an exploration of the Yellowstone River. Lewis was to take the others to the Great Falls via the Blackfoot River, then, with a detail of three men, explore more of the Marias River than he had in the spring of 1805. They expected to reunite at the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers about 1 August 1806.

Clark and his contingent returned to Fortunate Camp, emptied the cache, raised the six dugout canoes from their hiding places, and arrived at the Three Forks of the Missouri about noon on 13 July 1806. At 5 p.m. Clark, with ten men, plus Sacagawea and fifteen-month-old Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, set a course overland along the east fork of the Gallatin River.

Sacagawea’s Service

As he started over the mountains at today’s Bozeman they observed several Indian and buffalo roads heading northeast across the mountains at the head of the river. However, Clark reported, “the indian woman who has been of great Service to me as a pilot through this Country recommends a gap in the mountain more South which I shall cross.” This was one of the few times Sacagawea acted as the guide that legend has made of her, and it was crucial to Clark’s timely progress down the Yellowstone.

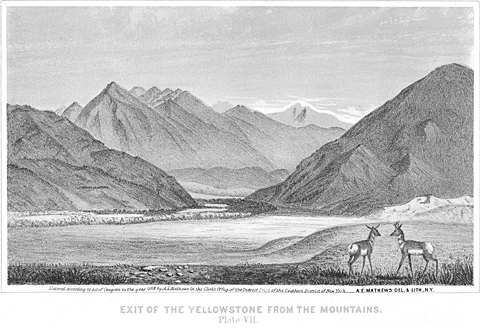

On the 15th, having crossed the mountains separating the Gallatin from the Yellowstone drainages, the party descended a slope (at right in photo) on “a well beaten buffalow road” toward the Yellowstone River. The Yellowstone flows north out of a mountain-bounded valley between low spurs of the Gallatin and Absaroka Ranges (background left), which Clark described as “rugged and covered with Snows.”

The party struck the river, “wide, bold, rapid and deep,” at the bend at about the center of the accompanying photo, in present-day Livingston, Montana. From where Clark stood, the fertile river basin now called Paradise Valley was hidden from his view, and the party pressed on downstream.

Yellowstone Arrival

Captain Clark Reaches the Roche Jaune

J. K. Ralston[1]Used by permission of the First National Bank of Livingston (Livingston, Montana) in cooperation with the Headwaters Chapter, Lewis & Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Inc.

Oil on canvas, 1960, 5.5′ by 17.5′.

When, in July of the following year, Captain Clark explored the Yellowstone from Livingston to the Missouri in July of the following year, he admired the “bold, rapid, and deep stream,” and judged from his pre-steamboat perspective that it was navigable throughout its entire length as far as he knew it. He commented on the abundance of furbearing animals: “the Yellowstone and its tributaries . . . abound in beaver and otter.”

On 15 July 1806, Captain Clark wrote:

Passing over a low dividing ridge to the head of a water Course [Bilman Creek] which runs into the Rochejhone, prosueing an old buffalow road which enlarges by one which joins it from the most Easterly branch of Galetins R. The mountains [the Absaroka Range and the Beartooth Mountains] to the S. S. E on the East side of the river is rocky rugid and on them are great quantities of Snow.

Mathews’ Descriptions

Lithograph from Pencil Sketches of Montana

by Alfred E. Mathews (1831-1874)

Published by the author in New York, in 1868. Special Collections, Mansfield Library, The University of Montana, Missoula.

One of Mathews’ prefatory comments to Pencil Sketches of Montana is especially illuminating with regard to the character and quality of early scenic photographs, and thought-provoking in the context of early 21st century graphic values:

The author has frequently been asked why he did not take a Photographic Instrument along, in order to photograph Mountain scenery; for it is generally supposed that a photograph of Mountain scenery is always perfectly accurate. This, however, is far from being the case. In taking a picture, the lens of an instrument must be adjusted to focus on a certain object or objects; and all others more distant, or nearer, will be more or less indistinct. Another disadvantage of an instrument is that objects near at hand are magnified, while those farther off are reduced in size. So apparent is this defect in large photographs of persons that a small picture is now first taken, and afterwards copied and enlarged. Shadows, too, are apt to be deepened and lights intensified. A good artist can, with ordinary care, produce a more accurate and pleasing picture with the pencil or brush.

Precisely what the Montana Post meant by describing the Yellowstone as “one of the most peculiar rivers on the continent,” is hard to guess, but what is truly peculiar is the extent to which its real and imaginary lengths have differed. Compare the figure of 1,600 miles for its overall length, with the United States Geological Survey’s calculation at 678.2 miles. Also, compare Clark’s estimate of 837 miles for the Lower Yellowstone—from the point where it exits the mountains at the Big Bend (Livingston, Montana) to its mouth—with the actual length of that stretch, which is 498.2 miles, a difference of 338.8 miles. Mathews’ distance is long by 58%; Clark’s estimate of the lower leg of the Yellowstone is 40% too long.[2]River Mile Index of the Yellowstone River. Water Resources Division, Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation (September 1976). River measurement today is based on the thalweg, German … Continue reading

What all these figures represent is that as of 1867 much remained to be done to complete the topographic and cartographic work begun by Clark. It continued soon after the Civil War, and Mathews’ sketches were important contributions. The upper Yellowstone River was explored by the Folsom-Cook expedition in 1869,[3]See William Goetzmann and Glyndwr Williams, The Atlas of North American Exploration From the Norse Voyages to the Race to the Pole (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992), 176-77. and by the Hayden expedition of 1871. Yellowstone National Park was established in 1872, and the USGS in 1879.

Alfred E. Mathews, a veteran of the 31st Ohio Volunteers in the Civil War, and famous for his on-the-spot drawings of battle scenes, especially “The Siege of Vicksburg” (1863), was one of the first American artists to focus attention strictly on the scenic highlights of the West, with a book of sketches of the Colorado Rockies (1866), and another of views of mountains along the Union Pacific Railroad (1869). Mathews was deeply moved by the scenery in the region that as recently as 1864 had become known as Montana Territory. He himself wrote of this particular vista:

Nothing can exceed the grandeur of the mountain scenery of the upper Yellowstone. The view represents its exit from these mountains, as seen from a point three miles below, and thirty miles from Bozeman, in the Territory of Montana. At the time the sketch was made (1867) no white inhabitants lived in the valley below the canyon, but several mining camps had been established in the mountains along the river and some of its tributaries. In the foreground of the view two antelopes are seen. These animals are quite numerous in the region, and during two days that the artist remained in the valley, he saw many large and small herds. Elk and mountain sheep also abound, and have frequently been seen in immense droves.

Mathews continued with a description of the river that had appeared in the weekly Montana Post in 1866.

The Yellowstone is one of the most peculiar rivers on the continent, and is 1,600 miles in length. It is this stream and some of its tributaries that give to the missouri its turbid appearance. Their waters, however, are all clear until nearing the Bad Lands—a region destitute of vegetation, and without springs or small streams. This barren waste is thickly strewn with animal and vegetable petrifications and curious stones; and has been little explored. The source of the Yellowstone is a clear, deep, beautiful lake, far up among the clouds; that is kept cool by drippings from the eternal glaciers Near this lake the river makes a tremendous leap down a perpendicular wall of rock, forming one of the highest and most magnificent waterfalls in America.

The scene Mathews captured hasn’t changed much since Clark and his contingent saw it in July of 1806, but Allenspur Dam, first conceived in 1902 and nearly begun in the 1970s, would have ruined it forever. The elevation of the riverbed at this point is about 4,540 feet above mean sea level; the summit of Canyon Mountain, on the right (west) side of the defile, is at 8,038 feet MSL. The proposed earthfill dam would have towered 380 feet above the river.

Last Undammed River

The Yellowstone is today the last great western river still undammed. This fact is no accident of history, writes William L. Lang. The river has had its defenders since at least the 1920s, when irrigators downstream wanted to dam the river at its outlet from Yellowstone Lake. No doubt because of the new National Park’s unique status as the world’s first, river-lovers found their cause successfully campioned by early environmentalists throughout the United States.[4]William L. Lang, “Saving the Yellowstone,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, 35 (Autumn 1985), 87–90.

The 1970s brought further threats to the river. Efforts to impound the Yellowstone’s waters behind a dam at Allenspur Gap, near Livingston, were turned aside when Montanans chose the Yellowstone’s world-class trout fishery over the needs of coal-generating plants, the heart-stopping beauty of Paradise Valley over the desires of irrigators, and a free-flowing Yellowstone over the demands of flood control.

The most recent battle over the Yellowstone’s fate involves ever more difficult choices. In the late 1990s, landowners along the river, fearful of severe flooding due to record snowpack, requested an unprecedented number of permits from the Army Corps of Engineers to build flood control structures along the Yellowstone’s banks. These concrete and stone structures, meant to stabilize the riverbank, appear to have unintended negative effects on the riparian or streambank habitat, causing, in the words of the Greater Yellowstone Coalition (GYC), a “steady and rapid erosion of the natural qualities of the river.”

A recent study by Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks confirmed that trout populations had dropped nearly 60 percent in the most extensively riprapped sections of the river. Concerned over these losses and over the possibility that, because of a lack of planning, the structures could actually cause worse flooding downstream, the GYC and four other groups have filed suit to enjoin the Corps of Engineers from granting further permits until the effects of “canalizing” the river could be studied fully. In May 2000, a U.S. District Court judge ruled that the Corps had fallen far short of its obligation to protect the river.[5]I am indebted to Dennis Glick, of the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, at http://www.greateryellowstone.org/ for information about current threats to the Yellowstone’s health, and the GYC’s … Continue reading

The Yellowstone has recently been named by the conservation group, American Rivers, as number five on its list of America’s ten most endangered rivers. Only through careful stewardship will this beautiful but damaged river remain, in the words of the Sierra Club’s Kris Prinzing, as the “last river in America that Lewis and Clark would still recognize.”

Related Reading

William L. Bryan, Jr, Montana’s Indians, Yesterday and Today (Second edition; Helena, MT: American and World Geographic Publishing, 1996).

Steve Chapple, Kayaking the Full Moon: A Journey Down the Yellowstone River to the Soul of Montana (New York: HarperCollins, 1993).

C. Adrian Heidenreich, “The Native Americans’ Yellowstone,” Montana The Magazine of Western History 35 (Autumn 1985), 2–17.

John C. Hudson, “Main Streets of the Yellowstone Valley: Town-building along the Northern Pacific in Montana,” Montana The Magazine of Western History, 35 (Autumn 1985), 56–67.

Dean Krakel, Downriver: A Yellowstone Journey (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1987).

William E. Lass, “Steamboats on the Yellowstone,” Montana The Magazine of Western History, 35 (Autumn 1985), 26–41.

Bill Schneider, Montana’s Yellowstone River (Helena, MT: Montana Magazine, 1985).

Carroll Van West, Capitalism on the Frontier: The Transformation of Billings and the Yellowstone Valley in the 19th Century (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993).

———, “Coulson and the Clark’s Fork Bottom: The Economic Structure of a Pre-Railroad Community, 1874–1881,” Montana The Magazine of Western History, 35 (Autumn 1985), 42–55.

Bozeman Pass and Sacajawea Park are a High Potential Historic Sites along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. Sacajawea Park is managed by the City of Livingston.—ed.

Sacagawea Park is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. This Livingston city park commemorates the expedition’s entry into the Yellowstone River valley.

Notes

| ↑1 | Used by permission of the First National Bank of Livingston (Livingston, Montana) in cooperation with the Headwaters Chapter, Lewis & Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Inc. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | River Mile Index of the Yellowstone River. Water Resources Division, Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation (September 1976). River measurement today is based on the thalweg, German for “valley way,” which is the line defining the lowest points along a river bed. Clark’s measurement was based on his estimates of the distance from one landmark to the next, day by day, throughout the course of his journey. Thus Clark’s estimates would have been somewhat shorter overall than a modern thalweg measurement. |

| ↑3 | See William Goetzmann and Glyndwr Williams, The Atlas of North American Exploration From the Norse Voyages to the Race to the Pole (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992), 176-77. |

| ↑4 | William L. Lang, “Saving the Yellowstone,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, 35 (Autumn 1985), 87–90. |

| ↑5 | I am indebted to Dennis Glick, of the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, at http://www.greateryellowstone.org/ for information about current threats to the Yellowstone’s health, and the GYC’s ongoing efforts to protect the river. |