Lewis and Clark appear to have been unaware of the existence of Chinook Trade Jargon. Some of the words they recorded became part of the jargon.

“Lolo,” Gibbs Dictionary of Chinook Jargon

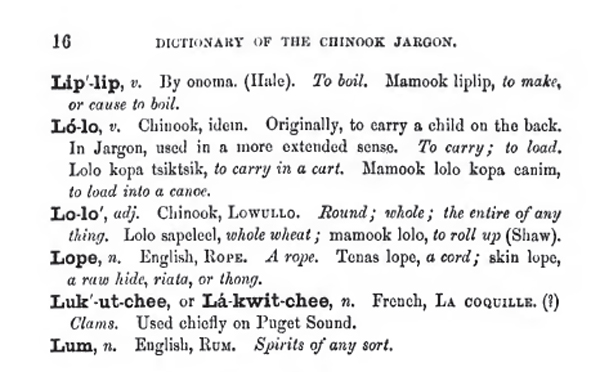

George Gibbs (1815-1873), A Dictionary of the Chinook Jargon, or, Trade Language of Oregon.

The entry reads:

Lólo, v. Chinook, idem. Originally, to carry a child on the back. In Jargon, used in a more extended sense. To carry; to load. Lolo kopa tsiktsik, to carry in a cart. Mamook lolo kopa canim, to load into a canoe. There is no record of Lewis or Clark encountering this term. However, the name is fitting for Lou Lou, the trapper that the Lolo trail may have been named after some years after the expedition. See on this site: Lolo in Trade Jargon and Naming the Lolo.

Chinookan, including Clatsop Nation |

200 |

Chinookan, having analogies with other languages |

21 |

Interjections common to several |

8 |

Nootka, including dialects |

24 |

Chehalis, 32, Nisqually, 7 |

39 |

Klikatat and Yakama |

2 |

Cree |

2 |

Chippeway (Ojibway) |

1 |

Wasco (probably) |

4 |

Kalapuya (probably) |

1 |

By direct onomatopoeia |

6 |

Derivation unknown, or undetermined |

18 |

French, 90; Canadian, 4 |

94 |

English |

67 |

—Editors Joseph Mussulman and Kristopher Townsend

Moving down the Columbia in the fall of 1805, the expedition passed numerous Indians living in permanent villages along the river. On 27 October 1805, at the Falls of the Columbia, the captains “took a Vocabelary” of the two languages they found there—those of the “E-nee-shur” and the “E-chee-lute.”[3]These were probably, respectively, the Wishram and the Wasco tribes, members of the Chinookan language group. Moulton, 5:346n. Clark noted that the languages were “verry different,” even though the tribes speaking them were “Situated within Six miles of each other.” At the same time, he observed that “maney words of these people are the same”—an indication, perhaps, that at least some of what he heard was Chinook jargon, a trade pidgin spoken extensively on the Pacific Coast from northern California to Alaska.[4]Frederick Webb Hodge, ed., Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico (Pageant Books, Inc., 1959), Part 2, 272–275. Coastal Indians would have used Chinook jargon to address white strangers, but … Continue reading

Lewis and Clark appear to have been unaware of the existence of Chinook Trade Jargon, which took its vocabulary from the languages of many tribes (including the Chinooks) and also incorporated some English and French picked up from traders.[5]Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinook_jargon. When Indians of the lower Columbia attempted to converse with expedition members they probably did so in this lingua franca of the Northwest tribes.[6]James P. Ronda, Lewis and Clark among the Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984; First Bison Book printing, 1988), 186. Ronda says that the Tillamook Indians spoke Chinook jargon to … Continue reading Trade jargon’s use on at least one occasion can be documented. When Clark visited a Clatsop village on 10 December 1805, he demonstrated his shooting prowess by knocking the head off a duck at 30 paces. In his journal description of the incident, Clark rendered phonetically the words of the astonished witnesses:

Clouch Musket, wake, com ma-tax Musket.

Clark translated this utterance as “good Musket do not under Stand this kind of Musket &c.” A liberal interpretation might phrase it, “That’s a good musket, but we don’t understand how it shoots so well.” Exactly how Clark got the meaning—who would have translated for him?—isn’t stated. Whatever the intended meaning, Clark’s phonetic transcription is remarkably close to the jargon words for “good . . . not understand.”[7]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001), 6:121–122n. The Indians used the word “musket,” which had entered jargon vocabulary. Clark had first noted the use of English among the lower Columbia tribes when the expedition was still pinned down by storms near Point Distress. Later, at Fort Clatsop, in a journal entry about English and American trading vessels visiting the mouth of the Columbia, Lewis wrote, “The Indians inform us that they [the traders] speake the same language with ourselves, and give us proofs of their varacity by repeating many words of English, as musquit, powder, shot, rifle, file, damned rascal, sun of a bitch &c.”[8]Ibid., 49 (entry for 15 November 1805) and 187 (9 January 1806).

Following Jefferson’s instructions to learn as much as possible about the native peoples they encountered, the captains dutifully recorded Indian vocabularies and did their best to distinguish one language from another. They recorded the “clucking tone” common to Chinookian languages—”a sound difficult to describe—but more like a hen or duck guttural & disagreeable,” as Clark later told Nicholas Biddle.[9]Moulton, 5:345 (entry for 27 October 1805); Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with Related Documents: 1783–1854, 2nd. ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), … Continue reading But often their linguistic analysis fell short. As James Ronda notes, “As was often the case, the explorers had a difficult time separating the names of villages, bands, tribes, and linguistic divisions.” To cite one example, they mis-categorized the language of the Tillamooks as Chinookian when in fact it belongs to the Salishan family.[10]Ronda, 184 and 186. The widespread use of Chinook jargon may have contributed to their confusion.

Language was a barrier to explorer-Indian relations on the coast. Clark complained that “we cannot understand the language of the natives Sufficiently” to ask informed questions of an ethnographic nature.[11]Moulton, 6:316. Entry for 15 February 1806. Lewis says something very similar in his entry for 9 January 1806 (Ibid., 186). Between body language and the smattering of vocabulary picked up over time, however, the explorers were able to trade and to converse, at least after a fashion, with the many Indians who called on them during their dreary winter at Fort Clatsop.

Notes

| ↑1 | Robert R. Hunt, “Eye Talk, Ear Talk: Sign Language, Translation Chains, and Trade Jargon on the Lewis & Clark Trail”, We Proceeded On, August 2006, Volume 32, No. 3, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original, full-length article is provided at https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol32no3.pdf#page=13. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | George Gibbs, A Dictionary of the Chinook Jargon, or, Trade Language of Oregon (New York: Cramoisy Press, 1863), vii–viii. |

| ↑3 | These were probably, respectively, the Wishram and the Wasco tribes, members of the Chinookan language group. Moulton, 5:346n. |

| ↑4 | Frederick Webb Hodge, ed., Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico (Pageant Books, Inc., 1959), Part 2, 272–275. Coastal Indians would have used Chinook jargon to address white strangers, but Clark would also have overheard them speaking among themselves in their native tongues. |

| ↑5 | Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinook_jargon. |

| ↑6 | James P. Ronda, Lewis and Clark among the Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984; First Bison Book printing, 1988), 186. Ronda says that the Tillamook Indians spoke Chinook jargon to strangers, and it is reasonable to generalize his statement to include all tribes in the region. |

| ↑7 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001), 6:121–122n. |

| ↑8 | Ibid., 49 (entry for 15 November 1805) and 187 (9 January 1806). |

| ↑9 | Moulton, 5:345 (entry for 27 October 1805); Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with Related Documents: 1783–1854, 2nd. ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 2:501–502. The artist Paul Kane, who visited the region in the 1840s, described Chinook clucking as “horrible, harsh spluttering sounds,” but he was nevertheless able to learn “this patois” well enough to “converse with most of the chiefs with tolerable ease.” J. Russell Harper, ed., Paul Kane’s Frontier, Including Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1971), 93. |

| ↑10 | Ronda, 184 and 186. |

| ↑11 | Moulton, 6:316. Entry for 15 February 1806. Lewis says something very similar in his entry for 9 January 1806 (Ibid., 186). |