During their Lakota Sioux difficulties, Lewis and Clark barely averted disaster in their encounter with Black Buffalo’s people.

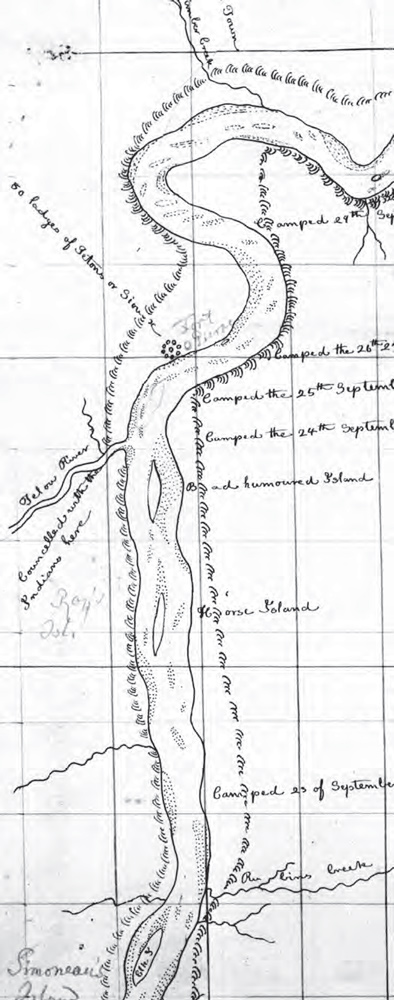

Route about 23 September 1804–1 October 1804

Clark-Maximilian Sheet 12

Courtesy Internorth Art Foundation, Center for Western Studies, Maximilian-Bodmer Collection, Joslyn Art Museum.

Drawn for an expedition by Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied, this 1833 map of the Missouri is based on an earlier map by William Clark which has since been lost. The Teton (now Bad) River enters from the left, opposite the present site of Pierre, South Dakota.

This seems such a simple story.[2]While built on the narrative framework provided in Chapter Two of my Lewis and Clark among the Indians (1984), this essay represents a thorough reconsideration of a crucial episode in the history of … Continue reading In late September 1804, many Lakota people in Black Buffalo’s Lakota Sioux Brulé band were camped near the place where today’s Bad River meets the Missouri. This should have been like any other fall season—a time to prepare for the rigors of a plains winter. But then, village circle life was interrupted by the arrival of strangers from down river.

Such strangers and their objects were nothing new. The Lakota Sioux (Tetons) had years of experience with white traders from St. Louis and the North West Company posts on the Des Moines and St. Peters rivers. But this was the largest, most heavily armed party that band chief Black Buffalo and his people had ever seen. And these strangers seemed less interested in trade than in talking about flags, medals, and a new great father. So the four days in September were filled with dramatic swings between friendship and hostility. There were times of welcome, with high ceremony and great ritual. There were nights bright with music, dancing, food and offers of more personal and intimate comfort. But there were also moments of confusion, dispute, harsh words, rude gestures, and ill-concealed contempt. And more than once tough talk seemed ready to become violent deeds. But in the end, at least seen from the bank, it seemed a simple story. The strangers came; we ate and argued; we stayed and they moved on. We were unimpressed and they seemed convinced we were now an enemy of their great father. Nothing really changes. The seasons come and go. Strangers come and go. We are here; we will always be here.

It does seem to be a simple story. Listen to it again. In the last days of September 1804 an American exploring party commanded by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark spent four days with the Teton Sioux at a place where the Teton River—it was not yet called the Bad—runs into the Missouri. The expedition was there to proclaim American sovereignty, make trade arrangements, and demonstrate the power of the young republic. Of all the Indians along the Missouri, Thomas Jefferson had singled out the Sioux as the nation on which he hoped Lewis and Clark would make “a favorable impression.”[3]Jefferson to Lewis, 22 January 1804, Donald Jackson, ed., The Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783–1854, second edition., 2 volumes (Urbana: University of Illinois … Continue reading But things did not go smoothly. There were shouting matches, pushing and shoving, and what Clark called insolent gestures and “vilenous intintious.”[4]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001), Vol. 3, pp. 111–112 (Clark). Hereafter cited as JLCE, with the … Continue reading Once these storms blew over there were good times, with sizzling buffalo steaks, strange music and dance, and offers of bed partners to warm the chilly nights. But mostly the American travelers worried for their safety. Diplomacy seemed less important than just moving on. So they threatened, cajoled, blustered, and held their ground. And after four days (and several sleepless nights) the Lewis and Clark Expedition did move on to what they hoped would be happier times at the Knife River Villages. Perhaps the president’s explorers thought: we came, we saw, and if we did not conquer at least we got through with skin and honor intact.

It does seem a simple story, whoever tells it. Seen from the bank or told from the boat, it is but a moment in time—easily explained and soon forgotten. But if the past teaches us anything it is that things are rarely what they seem to be. Simplicities dissolve into complexities; reality is always more messy than we imagine. What happened in those few September days where the Bad meets the Missouri was no simple story. If we look closely, pay attention, and listen carefully, we can hear and see stories larger, richer, and deeper—stories that take us into the very heart of the American experience.[5]James P. Ronda, Finding the West: Explorations with Lewis and Clark (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2001), pp. xi–xix.

Seeing Through Brulé Eyes

Let’s begin by asking a simple, radical question. Remember that the word “radical” means going to the root of things. Whose story is this? Who can best help us understand those tough days at the Bad? The answer has always been—this is a Lewis and Clark story. What they thought and said and did is the real story. But the inescapable truth is not so flattering to Jefferson’s travelers. In the long sweep of the Great Plains centuries Lewis and Clark were walk-ons at the Bad. They were the bit players in a drama larger and longer than they ever understood. We might learn more, appreciate more if we shifted our attention away from the captains and their boats, and tried to stand in the camp circle and see through Lakota eyes.

We can do this by recognizing three Teton Sioux men of the Brulés as central figures in the story. Without them there would be no Bad River story. Black Buffalo, Un-Tongar-Sar-bar or more properly Black Buffalo Bull, was widely recognized as the principal chief in his band. A skilled diplomat and distinguished warrior, Black Buffalo had recently (1803) attempted to engineer a truce between his people and their neighbors the Omahas. But that effort had been subverted by Black Buffalo’s most persistent rival for power and prominence. Known as the Partisan—a French word for daring war leader—Torto-hongar was bent on challenging Black Buffalo at every turn. Both men had warrior followings, and both understood that band politics was like public theater. There were parts to play, lines to speak, scenes to steal, and audiences to please. And there was a third man to account for in this Brulé cast of characters. Buffalo Medicine, Tar-ton-gar-wa-ker or more precisely Sacred Buffalo Bull, drifts in and out of this story. The American explorers named him as third chief, courted him, and perhaps saw him as a potential ally. Where he fit in the political struggle between Black Buffalo and the Partisan remains unclear. What is clear is this—all three men were astute politicians who understood both the power game and the larger economic issues present along the Missouri. Compared to these Lakotas, Lewis and Clark were country boys in the hands of real sharpies.

What happened at the Bad is a Teton Sioux story. Think of those four days from 25 September 1804 through 28 September 1804 as acts in a play, or think of the days as a ballet—part war dance, part dance of diplomacy; part personal, part national; part make-believe, part frighteningly real. This is a story with its own music, its own rhythms, tempos, and cadences. However we imagine it—whether as play, ballet, or Great Plains musical, remember that Lewis and Clark most often did not know their lines, didn’t know the steps, and often couldn’t read the score.

Day One

Day 1: 25 September 1804

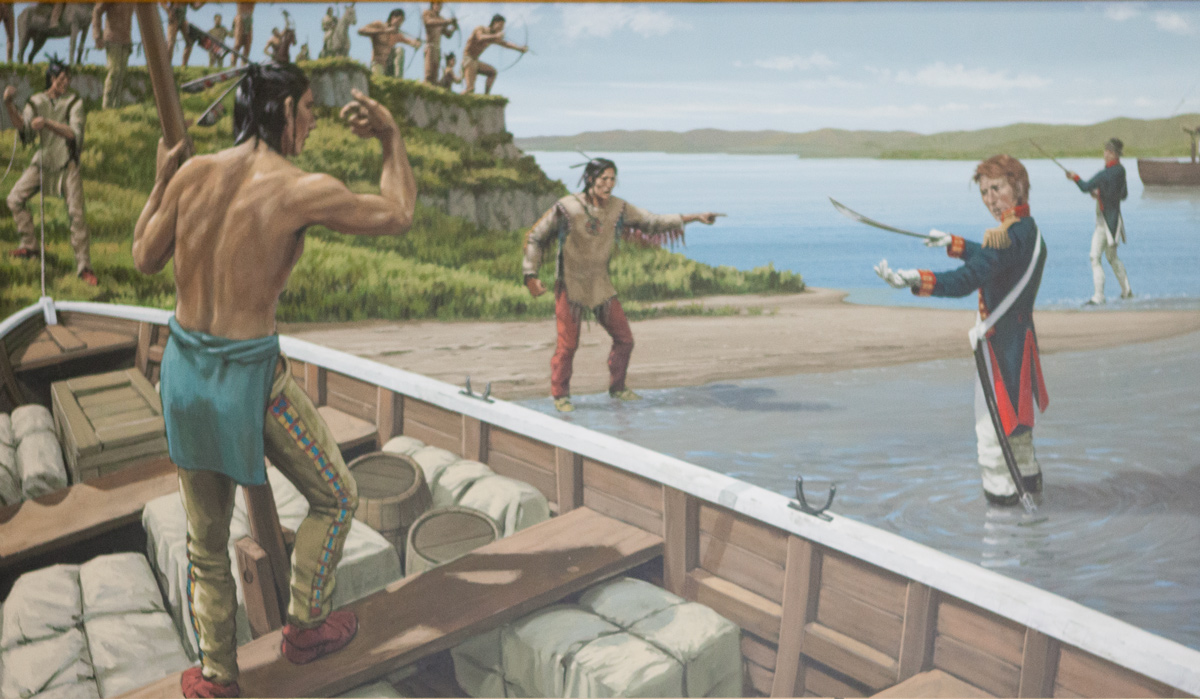

Painting created by Split Rock Studios, Sioux City, Iowa. Original in the collection of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation and photographed by Kristopher Townsend.

On the first day of the four-day meeting between the Teton Sioux and the Corps of Discovery, a warrior of the Partisan’s band locks arms around the barge’s (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) mast while Clark draws his sword and alerts the men for action.

This was a day filled with sound and fury, tough talk with weapons at the ready. It was a day when ceremony and diplomacy degenerated into pushing, shoving, and general bad temper. When Thomas Jefferson said he hoped to make a good impression on the Sioux, this is not what he had in mind.

Things began well enough. On a clear morning that promised good fortune, the American visitors picked out a convenient sandbar, erected an awning for comfort under the mid-day sun, hoisted the flag of the republic, and waited for Indians to show up. Nothing new here; Lewis and Clark had set up their road show before and would do it again in the coming months. At about 11 o’clock the Brulé chiefs and their retinues appeared. What followed was a remarkable blend of Native American and Euro-American diplomatic rituals. Each group fed the other, the Sioux bringing “great quantities of meet.”[6]JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 112 (Clark). By noon the eating was done and the talking could begin. Having left Pierre Dorion with the Yankton Sioux, Lewis and Clark now recognized that they lacked a reliable interpreter. Nonetheless, the council went ahead. There was smoking “agreeable to the usial Custom”[7]Ibid. (Clark). and then Lewis delivered his stock speech. If this meeting followed the pattern of others—and that seems a good guess—Lewis announced American sovereignty, told the Sioux they had a new great father, promised trade at good terms with St. Louis merchants, and urged peace with native neighbors.

Even with a skilled interpreter such a speech would not have been well received; without an adequate one it must have been almost unintelligible.

But without missing a beat the show rolled on. For Lewis and Clark this was serious business; for Black Buffalo and his friends it may have been nothing more than a pleasant diversion on a hot day. American troops paraded, showing off—so they thought—the martial power of the new nation. And as if to emphasize that power, the captains offered Black Buffalo a peace medal. He already had a Spanish flag; an American medal was one more appropriate gift for so important a man.

Virtually every European explorer who tramped or paddled through North America believed that native people could be awed or cowed by a show of manufactured goods, scientific instruments, and fire-spitting weapons. Lewis and Clark subscribed to that view and decided to invite the Teton chiefs on board the barge to see “Such Curiossities as was Strange to them.”[8]JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 113 (Clark). Hoping to extend the welcome, a whiskey bottle was handed around as well. At that moment everything came apart—or so it seemed to the Americans. Deciding that now was the time to make a bid for power, to intimidate the visitors, and perhaps embarrass Black Buffalo, the Partisan made his move. Pretending to be drunk, he staggered around the boat, becoming what Clark called “troublesome.”[9]JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 111 (Clark). River traders had warned Lewis and Clark this might happen, and those prophecies now seemed reality. Fearing that violence might erupt, the captains decided to hustle the chiefs ashore. Perhaps knowing that this was just a game—and a passing one at that—Black Buffalo and the others left “with great relectiance.”[10]Ibid. (Clark). They had played this game with other traders and it had worked before. Here were boats filled with goods. Surely some of those things should make their way from the boats to the bank. Not fully appreciating the complex rules in this Missouri River game, Clark soon followed, “with a view of reconsileing those men to us.”[11]JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 113 (Clark).

But reconciliation was not part of the dance that day. When Clark’s pirogue landed, an already troubled situation became potentially explosive. Three young Brulés who may have been part of the Partisan’s entourage seized the boat’s bow cable. At the same time, another warrior locked his arms around the pirogue’s mast. As he had done with traders before, the Partisan then moved directly against Clark. He spoke roughly, staggered up against him, complained that not enough presents had been offered, and bluntly told the American that the expedition could not advance up river. This was a test; it was intimidation; it was political showing off; and it had been often done before. Lewis and Clark were not being singled out for any special treatment. Given the presence of so many women and children, the Partisan was not about to start a shooting spree. There were real limits here but Clark did not recognize them. Instead, he drew his sword and alerted Lewis and the barge crew for action. The barge’s swivel gun was swung around and perhaps pointed at the crowd; soldiers with Clark made their weapons ready for action as well. But as quickly as the Partisan had created the tension, Black Buffalo eased it. Fearing casualties if fighting broke out, Black Buffalo took the cable in his own hands and forcefully ordered the warriors away from the boat. The Partisan had had his moment. Black Buffalo now reasserted his authority. From now on the story would be his, and his alone. Or so he hoped.

Surrounded by men with bows strung and arrows out of quivers, Black Buffalo and Clark now faced each other. The pointed and angry words they exchanged, passed through a woefully inadequate interpreter, reveal much about Brulé politics and expedition-Indian relations. Clark insisted that the expedition “must and would go on.”[12]JLCE, Vol. 9, p. 68 (Ordway). And as if to emphasize the force behind those words, Clark boasted that his men “were not squaw, but warriors.”[13]Ibid. (Ordway). Not to be outdone, Black Buffalo let loose his own rhetorical salvo. He shouted that “he had warriors too” and that if the Americans went on, he and his men would kill them one by one. Angered by these threats, Clark later recalled that he “felt My Self warm and Spoke in verry positive terms.”[14]JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 113 (Clark). Those “terms” included a pointed reminder that the expedition was sent by the Chief of the Seventeen Fires, whose warriors could be called in a moment to punish wayward Indians. And in a remarkable outburst, Clark claimed that he had “more medicine on board his boat than would kill twenty such nations in one day.”[15]JLCE, Vol. 10, p. 45 (Gass); JLCE, Vol. 11, p. 86 (Whitehouse).

All this verbal jousting might have gone on even longer except for the arrival of 12 more expedition soldiers “ready for any event.”[16]JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 113 (Clark). Most of the Brulé warriors quietly pulled back and Clark was left with the chiefs and a handful of Tetons. All the posturing, gesturing, and tough talk finally drained away any spirit for more confrontation. Black Buffalo, still in charge of the story, asked if women and children might see the barge’s wonders. It was an easy, face-saving request to grant. Clark agreed; Black Buffalo dropped the boat cable. But Black Buffalo still owned the story and its pace and he was determined to have the last word of the day. He was sorry, he told Clark, to have the Americans leave. Repeating an old formula, Black Buffalo explained that “his women and children were naked and poor and wished to get some goods” but he did recognize that these visitors from down river were not merchants.[17]JLCE, Vol. 9, p. 68 (Ordway). Black Buffalo then walked away, still in charge. Clark followed, offering to shake hands. When that offer was rebuffed it seemed that the day was over.

But not quite. Black Buffalo needed some visible statement that he was powerful, that he and he alone could shape the story. Staying on board the barge overnight might be just such a sign. Perhaps he recalled what Clark had said about the boat and the powers it might contain. As the American explorers made their way back to the barge, Black Buffalo and two of his warriors waded out and asked to be taken aboard the medicine boat. Later that night, as Black Buffalo and his men slept on board, Clark wrote about the day. “Their treatment of me was verry rough and I think justified roughness on my part.”[18]JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 113 (Clark). What he neglected to say was that diplomacy and making a “favorable impression” had been replaced by one objective—to leave these Indians behind and get up river. Nothing wrong with that, of course, except that one of the expedition’s diplomatic objectives was slipping away. And for Lewis and Clark, Indians who were supposed to become allies seemed more like enemies. Even more telling, real initiative remained in Teton hands. No wonder that the expedition named its anchorage that night “Bad humored island as we were in a bad humor.”[19]JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 114 (Clark).

Day Two

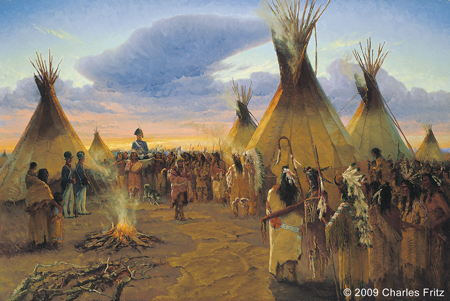

Evening of Ceremony with the Teton Sioux

26 September 1804

36″ x 54″ oil on canvas

© 2009 by Charles Fritz, http://charlesfritz.com. Used by permission.

The first day was all strut and show. The Corps of Discovery tried to strut its stuff with speeches, parades, and barge curiosities. Black Buffalo’s people showed all their tricks and strategies so often used to frighten white traders and keep control of river traffic in native hands. In the rhythms of threat and welcome, bluster and greeting, the second day was dramatically different. Now the banks of the Missouri were lined with Indians all intently watching the expedition spectacle. Clark thought the Indians displayed “great anxiety.”[20]JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 117 (Clark). Perhaps some worried about what medicine the Americans might possess; others might have thought they had lost the battle of wits and wills so often won before. Or maybe Clark was just wrong about what those faces revealed, projecting on them his own worries about the days to come. What looked like anxiety might have been just plain curiosity. After all, the Lewis and Clark Expedition was rapidly becoming the greatest tourist attraction on the river, not to be missed whatever the danger.

But this is still Black Buffalo’s story. Thinking he might keep the visitors in his domain just a bit longer, he asked the expedition to land so that there might be more time for visiting. Lewis and Clark now had to make a real choice. They could spend another day and try to patch up relations with the Sioux or they could make good on their determination to move up river. Once again, Black Buffalo was in charge and he evidently made the decision for the Americans. With Lewis in tow, Black Buffalo headed for the Brulé village while Clark stayed with the barge. As things fell out, this was a day of colorful ceremony and solemn ritual, all mixed with food, music, and dancing. And as if to symbolize that this day was different from the one before, Lewis and Clark were carried on white buffalo robes into the great council lodge.

The scene that night in the Brulé village came right out of a George Catlin painting. Fires glowed through translucent tipis as women prepared vast quantities of food for the coming feast. Inside the council lodge some 70 elders and prominent men sat in a circle. Lewis and Clark were in places of honor next to Black Buffalo. If the Partisan was there—and that seems unlikely—he escaped expedition notice. Directly in front of the chiefs a six-foot circle had been cleared for holy pipes, pipe stands, and medicine bundles. American and Spanish flags were also on display. Lewis and Clark noticed the Spanish ensign but wisely decided to ignore it. There was no evidence that night—or in the days to come—that the Tetons recognized the sovereignty of either Spain or the United States.

The rituals of diplomacy began when a Brulé elder stood and, at least so Lewis and Clark believed, “Spoke aproving of what we had done.”[21]JLCE, 3, p. 116 (Clark). But the old man went on to say that his people were poor and that the Americans should not trade with the upriver tribes. What Lewis and Clark still did not understand was the role Sioux middlemen played in the larger Missouri River economic system. There is no expedition record of Lewis and Clark’s reply but they probably repeated the usual words about peace, trade, and the need for the expedition to move on. Because Lewis and Clark learned earlier in the day that there were many Omaha prisoners in the Brulé villages, the Americans saw this as an opportunity to promote Teton-Omaha peace. Clark called on Black Buffalo to free those captives. Black Buffalo’s own attempt at an Omaha peace had been disrupted the year before by the Partisan. In early September, some two weeks before Lewis and Clark arrived, a Teton war party had raided an Omaha village, killing more than 75 Omahas and taking many prisoners. Now everyone expected a counter raid any day. What business was it for visitors to stir in such troubled waters?

The council reached its dramatic climax when Black Buffalo “rose with great State” to address the gathering.[22]JLCE, 3, p. 118 (Clark). Again hindered by the lack of a skilled interpreter, Lewis and Clark understood little of what the chief said. Clark noted in his journal that the chief spoke “to the Same purpote” as the Brulé elder. Perhaps Black Buffalo used his oratorical skills to further the principal Teton Sioux aim—to keep the expedition from opening direct trade with the Arikaras and other upper Missouri village peoples. His speech finished, Black Buffalo took up the most sacred of the pipes and pointed it in each of the cardinal directions. Before lighting the pipe, he offered a prayer. Still holding the pipe, the chief took some tender dog meat and made what Clark believed was a “Sacrefise to the flag.”[23]Ibid. (Clark). Just what that “sacrefise” meant remains unclear. It certainly did not represent any Sioux recognition of American sovereignty. These solemnities complete, the pipe was passed around for all to smoke.

Once the council was over it was time for a memorable, belly-filling feast. The Americans were presented with all the Sioux delicacies, including platters of roast dog, buffalo, pemmican, and prairie turnips. At nightfall a large fire was made in the center of the village to light the way for musicians and dancers. Throughout the night Brulé men and women sang and danced, recounting the exploits of great warriors and the humiliations of hated enemies. All of this, “done with Great Chearfullness,” went on until midnight.[24]JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 119 (Clark).

As a weary Lewis and Clark headed to the barge, they were offered young women as bed partners. For the Sioux, this proposal combined hospitality and diplomacy. Clark understood the meaning of the offer, writing later that “a curious custom with the Souix as well as the rickeres [Arikaras] is to give handsom squars to those whome they wish to Show some acknowledgements to.”[25]JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 163 (Clark). Repeating the offer the following night, the Indians made it clear that the women stood for the whole band. Clark was urged “to take her and not dispise them.”[26]JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 121 (Clark). Here Clark was up against the dilemma that confronts every traveler who crosses from one culture to another. Whose values and customs should guide the day and rule the night? To have accepted the woman would have violated Clark’s own moral principles; to reject her would show bad manners, ill grace, and further complicate an already-confused situation. Clark made his choice and slept alone.

Day Three

There had now been two days of intense excitement for both the Brulés and their visitors. And Clark slept badly on the night of the 26th. The third day of the Teton confrontation had its own odd rhythm and pace to it. At various times during the day both captains went ashore to pay courtesy calls on the Teton chiefs. We know little about those visits except that they attracted considerable attention. Lewis and Clark were now a curiosity not to be missed and they drew crowds everywhere they went. And that evening there was a second round of feasting, dancing, and singing. But all of this could not hide a growing tension in the air. Black Buffalo and the Partisan were still rivals; the American expedition was heading up river no matter what the Sioux did to detain them; and there were rumors of an imminent Omaha attack. And once again the visitors from the medicine boat rejected Sioux women.

All this pent-up tension and emotion exploded that night when a poorly steered pirogue slammed broadside against the barge, breaking the anchor cable. Clark’s shouts and the general confusion alarmed Black Buffalo. Convinced that the Omahas were attacking either his village or the Americans, he and some two hundred armed men rushed to the water’s edge, ready for a fight. Eventually the source of the alarm became clear and most of the warriors drifted back to the village. An exhausted and frazzled William Clark—remember he had slept poorly the night before—was ready to believe the worst about Black Buffalo’s people. Other expedition journal keepers—most notably sergeants John Ordway and Patrick Gass, and private Joseph Whitehouse—acknowledged that the Tetons were afraid of an Omaha attack, and that they did want to help the endangered American vessel. But Clark saw it differently. He was persuaded that what Black Buffalo and his people did was a “signal of their intentions (which was to Stop our proceeding on our journey and if Possible rob us.)”[27]JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 123 (Clark). This view was reinforced by what Pierre Cruzatte heard from the Omaha prisoners. Those captives told Cruzatte—who was part-Omaha and spoke the language—that the Sioux were intent on stopping the Corps of Discovery. So it was yet another sleepless night.

Black Buffalo’s people had now played host to the American visitors for three days. Those were times filled with isolated moments of trouble and misunderstanding and long periods of friendly visiting and good company. But the central issue remained unresolved and potentially explosive. Lewis and Clark wanted Sioux guarantees of safe passage on the Missouri for St. Louis traders. Such guarantees really amounted to acknowledging American sovereignty. Moving up river to the Mandan villages without giving any more gifts or paying any more social calls now came to represent to Lewis and Clark a personal and a national victory. That determination collided with the equal determination of Black Buffalo and the other chiefs to both advance their own prestige and protect Sioux economic interests. In the eyes of men like Black Buffalo and the Partisan, the continued presence of the American expedition posed something of a dilemma and an embarrassment. Both men needed to act forcefully to vindicate personal claims to leadership. Lakota people expected their chiefs to obtain gifts from river traders. A chief who could not deliver was bound to have his authority openly questioned. At the same time, faced with a well-armed party, the chiefs feared pressing their demands too far. If there was a bloody incident with Indian casualties, the chiefs would surely lose stature. Pressure tactics that proved effective in intimidating poorly-armed traders who needed Sioux cooperation would not work against a military expedition whose goals went far beyond the ledger book. It was against this background of cross purposes, face saving, and the expedition’s determination to leave the Bad River country that the last day of the Teton Sioux confrontation played itself out.

Day Four

Much of that morning was spent in a hapless search for the barge anchor. By mid-morning, Sioux onlookers lined the banks, watching what must have seemed a most unusual piece of work. As the captains were about to order the sail hoisted, Black Buffalo and the other chiefs appeared. Allowed to come on board for what Lewis and Clark hoped would be their last visit, the chiefs began their now-familiar routine. There were demands that the expedition delay its departure—demands made more ominous by the presence of well-armed warriors. Several of the Partisan’s followers seized the barge bow line. When Clark complained to Black Buffalo, the Brulé chief hurried to reassure Lewis that the Indians only wanted tobacco. Weary and angry at all these demands and delays, Lewis refused to give any more gifts. Once again he ordered all hands ready for departure, had the sail hoisted, and detailed one man to untie the bow cable.

At that moment what had been simmering for three days seemed ready to boil over. The bow cable, first untied by a crewman, was again seized by several of the Partisan’s warriors. At the same time, the Partisan demanded a flag and some tobacco. Lewis responded angrily, ordering all Indians off the boat while Clark threw a carrot of tobacco on the bank. Near to losing his temper, Clark took the firing taper for the port swivel gun in his hand and “spoke so as to touch his [Black Buffalo’s] pride.”[28]JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 124 (Clark). Clark did not record his sarcasm in his journal but he later told Nicholas Biddle, “I threw him tobacco saying to the chief you have told us you are a great man—have influence—take this tobacco and shew us your influence by taking the rope from your men and letting go without coming to hostilities.”[29]“The Biddle Notes,” in Jackson, Letters, 2: 518. Clark also had a “rangeling” exchange with the Partisan. Violence seemed seconds away as warriors hurried women and children away from the bank. That had not happened before, and it was a sure sign of just how desperate things had suddenly become.

It was Black Buffalo were finally calmed the impending storm. In one way or another the story on these four days had always been his to tell, and now once again he reasserted control over the narrative flow of events. Black Buffalo promised the expedition safe conduct if tobacco, always a ceremonial tribute, was given to the warriors holding the cable. He ignored the Partisan’s demands—just one more way to gain stature over a dangerous rival. Perhaps not fully understanding what Black Buffalo was offering, Lewis and Clark balked at the compromise, saying that they “did not mean to be trifled with.”[30]JLCE, Vol. 9, p. 72 (Ordway). Seeing the captains hesitate, Black Buffalo played his own card. “He was mad too, to see us stand so much for one carrot of tobacco.”[31]Ibid. (Ordway). Black Buffalo’s sharp words seemed to bring Lewis to his senses and he tossed the tobacco to the Indians. Black Buffalo did his part, jerking the cable from the warriors’ hands. At that instant the Teton confrontation was over.

In those moments when Clark was ready to fire the swivel gun, when Brulé warriors had bows strung, when the Partisan was shouting defiance, and when women and children fled from the bank, it was Black Buffalo who showed both firmness and the ability to compromise. Perhaps he now realized that nothing further could be gained by delaying Lewis and Clark. There would be other parties from St. Louis, less well-armed, with more goods, and easier to intimidate. Allowing one boat to pass was hardly a defeat. Black Buffalo had obtained ceremonial tribute from the Americans and had lost nothing in the eyes of his people. But the ambitions of the Partisan were yet unfulfilled. His contest with Black Buffalo gave him reason to continue the confrontation. The last minutes of the encounter were less a conflict between Indians and the Corps of Discovery than a tussle between rival band leaders. In the end it was Black Buffalo who engineered a way out, allowing each party to escape with some dignity intact and without bloodshed.

“Pirates of the Missouri”

So it is not a simple story after all. What does it all mean? How and why did those tough days at the Bad happen at all? William Clark was sure he knew the answers to those questions. During the winter at Fort Mandan, Clark prepared his comprehensive “Estimate of the Eastern Indians,” and it was in this document that he let loose a torrent of harsh language aimed at Black Buffalo’s people. Labeling the Teton Sioux as “the vilest miscreants of the savage race” and “the pirates of the Missouri,” Clark insisted that American commercial interests would never be safe until the Sioux were “reduced to order, by coercive measures.”[32]JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 418 (Clark). And one of those coercive measures, so Lewis and Clark came to believe, was an alliance of village Indians—Arikaras, Mandans, and Hidatsas—aimed against the Sioux. After September 1804 such an anti-Sioux alliance became the centerpiece of expedition diplomacy on the plains. So much for Jefferson’s desire to make a “friendly impression” on the Sioux. Never mind that village Indians would never accept such an alliance. And never mind that Clark’s understanding of what happened at the Bad was both naïve and wrongheaded.

Thinking about the uneasy days at the Bad River as Black Buffalo’s story, we might pay attention to two things that Lewis and Clark either did not know or failed to appreciate.

First, there was politics and power. In 1804 the politics of the northern Great Plains was every bit as complex as the politics of Washington, D.C. Lewis and Clark arrived at an exceptionally tense moment in Brulé band political history. Black Buffalo and the Partisan had long been rivals. Recent troubles with the Omahas had only intensified the competition between these two men and their followers. Playing to the native galleries, Black Buffalo and the Partisan were ready to use any opportunity to enhance personal prestige and influence. Politics is an unpredictable play with uncertain consequences and unforeseen conclusions. Lewis and Clark came on stage without the appropriate script, knowing neither their lines nor the roles of the other actors. Little wonder that all the nuances and subtleties of the performance were lost on Jefferson’s traveling troubadours.

Economic Middlemen

The story Black Buffalo tells about those days at the Bad is more than the competition between two forceful men. By 1804 the Teton bands along the Missouri were part of a large-scale economic trade system that reached east into present-day Minnesota, north up the Missouri, and then deep into the West. Anthropologists call this the Middle Missouri Trade System. We might think of it as a circle of hands—native and non-native—exchanging all sorts of goods and services. Each year the Teton Sioux bands traveled to a trade fair known as the Dakota Rendezvous, held on the James River in east-central South Dakota. There the Tetons met Sisseton and Yankton Sioux who had obtained European manufactured goods from North West Company posts on the Des Moines and St. Peters rivers. The Tetons used those items and buffalo robes in their agricultural trade with Arikara village farmers. With Sioux population growing, a secure food supply was essential. So long as the Tetons could control the flow of European goods to the village farmers, the Sioux position would be reasonably safe. But if the villagers gained easy direct access to St. Louis traders, the role of the Tetons as brokers and middle men would be lost. Black Buffalo and his people understood all of this. They were not the pirates of the Missouri; they were the river toll keepers, intent on preserving their place in a complex, ever-changing river world.

This story—Black Buffalo’s story—is centrally important because it draws us back to fundamentals, the essentials in the history of North America.

First: There are no simple stories. All good stories—and the story of Black Buffalo’s people and the Corps of Discovery is surely a good story—are complicated stories. One of the best things we can do is embrace complexity. Black Buffalo, the Partisan, Lewis, and Clark did not live in some simple time, remote from change and close to the Garden of Eden. Their worlds were as complex as ours.

Second: Black Buffalo’s West, the West of Lewis and Clark, was an extraordinarily diverse place. Black Buffalo ushers us into a West of remarkable cultural and biological diversity. It was a crazy-quilt world then; it is now. Black Buffalo reminds us that the citizens of North America come in many shapes, sizes, genders, and colors.

Third: And most important—this story is all about mutual encounter, shared discovery. Like Lewis and Clark, Black Buffalo and his people were explorers. They lived in an ever-changing, shape-shifting world. The Missouri River world of 1804 was not what it had been a century before. Tidal waves of disease, oceans of European goods, and the growing presence of Euro-American outsiders made it a new world. Black Buffalo and his people had to explore that world, had to make sense of it, just as Lewis and Clark were doing.

Writing about the Missouri River and the Great Plains, George Catlin said that it was “a place where the mind could think volumes.”[33]George Catlin, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of the North American Indians, 2 volumes (1844; reprint, New York: Dover Publications, 1973), Vol. 2, p. 3. As we consider the events at the Bad River nearly two hundred years ago we might work at thinking volumes. We might consider that for the United States, the 19th-century West began on the plains at the Bad River with a confrontation between Black Buffalo’s people and American soldiers, and that same century ended not more than 135 miles south and west of that place at Wounded Knee with a similar confrontation between Big Foot’s people and American soldiers. The two places—the Bad River and Wounded Knee—bracket a century whose events and people still live in memory, walk in the present, and, in ways often unknown to us, shape the future.

Bad River Encounter Site is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. The site is located in Fischers Lilly Park of the city of Fort Pierre.—ed.

Notes

| ↑1 | James P. Ronda, “Tough Times at the Bad,” We Proceeded On, May 2002, Volume 28, No. 2, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original article is at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol28no2.pdf#page=13. The original was adapted by the author from his keynote address delivered at the August 2002 Lewis and Clark Trail Foundation’s annual meeting in Pierre, South Dakota. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | While built on the narrative framework provided in Chapter Two of my Lewis and Clark among the Indians (1984), this essay represents a thorough reconsideration of a crucial episode in the history of the expedition and the northern Great Plains. |

| ↑3 | Jefferson to Lewis, 22 January 1804, Donald Jackson, ed., The Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783–1854, second edition., 2 volumes (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), Vol. 1, p. 166. |

| ↑4 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001), Vol. 3, pp. 111–112 (Clark). Hereafter cited as JLCE, with the appropriate journal keeper’s name. |

| ↑5 | James P. Ronda, Finding the West: Explorations with Lewis and Clark (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2001), pp. xi–xix. |

| ↑6 | JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 112 (Clark). |

| ↑7 | Ibid. (Clark). |

| ↑8 | JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 113 (Clark). |

| ↑9 | JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 111 (Clark). |

| ↑10 | Ibid. (Clark). |

| ↑11 | JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 113 (Clark). |

| ↑12 | JLCE, Vol. 9, p. 68 (Ordway). |

| ↑13 | Ibid. (Ordway). |

| ↑14 | JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 113 (Clark). |

| ↑15 | JLCE, Vol. 10, p. 45 (Gass); JLCE, Vol. 11, p. 86 (Whitehouse). |

| ↑16 | JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 113 (Clark). |

| ↑17 | JLCE, Vol. 9, p. 68 (Ordway). |

| ↑18 | JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 113 (Clark). |

| ↑19 | JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 114 (Clark). |

| ↑20 | JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 117 (Clark). |

| ↑21 | JLCE, 3, p. 116 (Clark). |

| ↑22 | JLCE, 3, p. 118 (Clark). |

| ↑23 | Ibid. (Clark). |

| ↑24 | JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 119 (Clark). |

| ↑25 | JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 163 (Clark). |

| ↑26 | JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 121 (Clark). |

| ↑27 | JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 123 (Clark). |

| ↑28 | JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 124 (Clark). |

| ↑29 | “The Biddle Notes,” in Jackson, Letters, 2: 518. |

| ↑30 | JLCE, Vol. 9, p. 72 (Ordway). |

| ↑31 | Ibid. (Ordway). |

| ↑32 | JLCE, Vol. 3, p. 418 (Clark). |

| ↑33 | George Catlin, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of the North American Indians, 2 volumes (1844; reprint, New York: Dover Publications, 1973), Vol. 2, p. 3. |