Leaving Clarksville

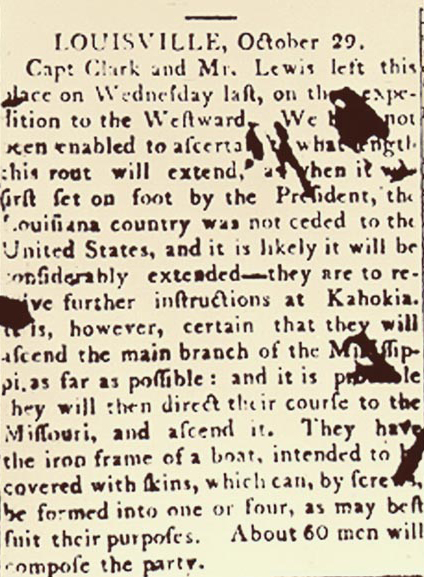

The 29 October 1803 issue of the Farmer’s Library carried news of the departure that was picked up by the Kentucky Gazette. “LOUISVILLE–Capt. Clark and Mr. Lewis left this place on Wednesday last [26 October 1803], on their expedition to the Westward,” it reported. The article then speculated about their ultimate destination possibly being the Missouri River, the final size of the party, and the innovative iron frame boat.[1]Kentucky Gazette, 8 November 1803. The article, datelined Louisville, 29 October 1803, concluded with the unattributed report that “about 60 men will compose the party.”

Transcript:

LOUISVILLE, October 29

Capt. Clark and Mr. Lewis left this place on Wednesday last, on the expedition to the Westward. We have not been enabled to ascertain what length this rout will extend, as when it was first set on foot by the President, the Louisiana country was not ceded to the United States, and it is likely it will be considerably extended—they are to receive further instructions at Kahokia. It is, however, certain that they will ascend the main branch of the Mississippi, as far as possible: and it is probable they will then direct their course to the Missouri, and ascend it. They have the iron frame of a boat, intended to be covered with skins, which can, by screws, be formed into one or four, as may best suit their purposes. About 60 men will compose the party.

24 October 1803 might have been planned as the day of departure for the nucleus of the Corps. If so, something happened to delay the explorers another two days. On the 24th, Jonathan went into Louisville and then on to Clarksville. He spent the night there with William Clark but then went back across the river to Louisville and spent the night of the 25th there. On the 26th, William was in Louisville at the Jefferson County Court House to file legal papers. Perhaps the Clark brothers–and maybe Lewis–left Louisville together for the lower landing at the foot of the Falls and then across the river to Clarksville on that famous day. By mid-afternoon it was time to leave. The barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) and pirogue loaded, the men aboard, and final good byes said, the initial personnel of what was eventually to be called the Corps of Discovery pushed off down the Ohio on their journey to the Pacific. Tears undoubtedly were shed and arms frantically waved in farewell. Jonathan wasn’t quite ready to part with his brother. He boarded the barge and went about ten miles downstream with the Corps as they “set off on a western tour.”[2]Jonathan Clark Diary, 24–26 October 1803, The Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Ky.; William Clark Power of Attorney, Jonathan Clark Papers—Temple Bodley Collection, The Filson Historical … Continue reading

Pending the actual transfer of Louisiana from Spain to France to the United States, Lewis’s real destination was still officially a secret, which accounts for the information that their primary objective is to explore the upper Mississippi River. Lewis’s “iron boat” remains an object of exceptional interest. By this point it has become clear that the handling of the barge and its cargo was going to require much more manpower than originally had been thought. Congressional approval had been voted for a budget of $2,500 for a party of “an intelligent officer with ten or twelve chosen men.”

Lack of Information

Information is almost nonexistent for the Corps’ trip from the Falls to Fort Massac. Jonathan Clark mentions parting with the explorers at his son-in-law’s farm in present west Louisville, and Lewis records stopping at the first Kentucky settlement below Louisville.[3]Moulton, 2:108. Lewis noted in his journal for 23 November 1803, while at Louis Lorimier’s at Cape Girardeau, that a very pretty girl there was “much the most descent looking feemale I … Continue reading That settlement might have been West Point, at the mouth of Salt River, where John Shields lived. The Ohio was still low, and its channels meandered from one side of the river to the other, leading the boats past islands, rocks, and sandbars. With the additional manpower of the “Nine Young Men” and York, progress was steady. The scenery must have been beautiful that time of year, with fall colors splashed across the forests lining the banks. The Corps probably took advantage of any settlements they encountered. Contemporary accounts describe the Kentucky side as dotted with farms and small settlements, and the Indiana side as wilderness and Indian country. Yellow Banks (now Owensboro) and Henderson (also known as Red Banks), where a Clark family friend lived, might have been stops. The boats passed the mouths of many creeks and rivers, the Salt, Blue, Wabash, Green, Tradewater, Cumberland, and Tennessee among them. This was familiar territory for some, if not most, of the men. William Clark, and almost certainly York, had boated down the Ohio several times.

Fort Massac

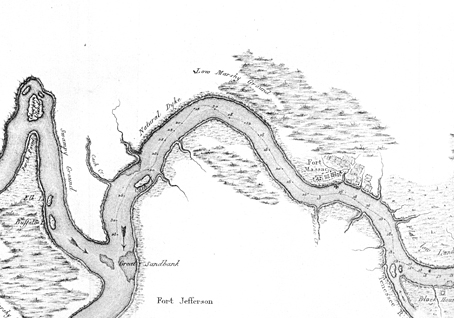

On 11 November 1803, the little flotilla arrived at Fort Massac. Here, Lewis had arranged to rendezvous with a detachment of soldiers from South West Point, Tennessee. When they were not there, Lewis and Clark hired a civilian to go get them. That person was George Drouillard. Of Shawnee and French-Canadian parentage, Drouillard became one of the most important members of the Corps of Discovery. Having lived at Massac Village west of the fort, as well as across the Mississippi River at Cape Girardeau, Drouillard was added to the Corps as an interpreter and hunter. He did important service as both. If the captains had an important or dangerous mission, Drouillard almost invariably was called on to help achieve it.

Other recruits were also acquired at Fort Massac. More manpower was needed for the upcoming segment of the journey. Not only were some or all of the temporary crew who had helped bring the boats down the Ohio turning back at Massac, but once the Corps entered the Mississippi it would be sailing against the current. Clark stated that “we Calld for a detachment of 14 men from that garrison” to accompany us as far as Kaskaskees & How many of these soldiers joined the permanent party isn’t known. At least two and perhaps more were drawn from Massac.[4]Holmberg, 60, 66-67n, 69n. South West Point was on the Tennessee River at Kingston, west of Knoxville. Why Lewis had requested troops from a post in that area when he would be passing two others on … Continue reading

At Fort Massac on 11 November, Lewis briefly began keeping his journal again. Two days after arriving at the post, the explorers left for the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi–just a short distance away. On the evening of 14 November 1803, the Corps arrived there. The explorers spent five days at the confluence, investigating the area, visiting residents both red and white, and beginning their scientific endeavors. On 20 November 1803, the Corps began ascending the Mississippi River.[5]Moulton, 2:85-95; Holmberg, 60-61, 67-69n.

The first major stretch of the Corps of Discovery’s journey had been accomplished. Some 1,000 miles and two and one-half months lay behind them. In mid-November of 1803 the explorers were only on the threshold of their adventure. Some 8,000 miles and three years still lay ahead for them. The vast country up the Missouri and west of the Rockies still beckoned. But before then these dauntless men still faced completing the formation of the Corps and their first winter encampment.

Much had been accomplished on this important stretch of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. From the military barge being built at Pittsburgh, to Lewis and Clark meeting to form one of the most famous partnerships in history, to the recruitment and enlistment of the Corps of Discovery’s crucial foundation, this American odyssey had been successfully launched toward success and fame on the waters of the Ohio River.

Notes

| ↑1 | Kentucky Gazette, 8 November 1803. The article, datelined Louisville, 29 October 1803, concluded with the unattributed report that “about 60 men will compose the party.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Jonathan Clark Diary, 24–26 October 1803, The Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Ky.; William Clark Power of Attorney, Jonathan Clark Papers—Temple Bodley Collection, The Filson Historical Society; Holmberg, 64n. |

| ↑3 | Moulton, 2:108. Lewis noted in his journal for 23 November 1803, while at Louis Lorimier’s at Cape Girardeau, that a very pretty girl there was “much the most descent looking feemale I have seen since I left the settlement in Kentuckey a little below Louisville.” |

| ↑4 | Holmberg, 60, 66-67n, 69n. South West Point was on the Tennessee River at Kingston, west of Knoxville. Why Lewis had requested troops from a post in that area when he would be passing two others on the way west was apparently a result of what he intended his original route to be—through Tennessee to Nashville and then down the Cumberland River to the Ohio. He states as much in his 20 April 1803, letter to Jefferson (see Jackson, 1:38). Lewis’s plan was to have a “keeled boat” built at Nashville and man it with a detachment from the garrison at South West Point. Having a boat built at Nashville changed to having it built at Pittsburgh, but the plan to detail men from South West Point remained. The two Fort Massac soldiers indicated by records to have joined the permanent party were Joseph Whitehouse and John Newman. Whitehouse accompanied the Corps on the entire Expedition but Newman did not, being court-martialed in the fall of 1804 and sent back from Fort Mandan with the temporary party and barge in the spring of 1805. See Holmberg, 67n and 69n for further speculation regarding this detachment. |

| ↑5 | Moulton, 2:85-95; Holmberg, 60-61, 67-69n. |