Between 13-Mile Camp and Rocky Point on 28 June 1806, not only did they have new trail to see, but the views of the Bitterroot Mountains were spectacular.

If fog clears from the top down,

expect some rain.

If fog clears from the bottom up,

the weather will be fair.

Below 13-mile Camp

© 1 July 2009 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Abundant grass for their tired, hungry horses brought the party to an early halt on 28 June 1806, having covered only 13 miles over deep but sturdy snow since leaving their Spring Mountain bivouac. They struck camp early the next morning, and, while “the fog rose up thick from the hollars” according to Sgt. John Ordway, the Corps “pursued the hights of the ridge on which we have been passing for several days.” Five miles and a couple of hours later they reached its eastern terminus at 6,208 feet above sea level, today suitably named Rocky Point. Understandably, they crossed over the peak without pausing for one last view of “those tremendious mountanes . . . in passing of which,” Clark would assert two days later, “we have experienced Cold and hunger of which I shall ever remember.” They had seen more than enough of the Bitterroots for one lifetime. Today, the view from the fire lookout tower is unquestionably the most comprehensive from any single point on K’useyneiskit.

With imaginable but unspoken satisfaction the party “bid adieu to the snow” and hurried down the east ridge of the mountain to the Crooked Fork (their “North Fork”) of the Lochsa River. There they hastily nourished themselves on the flesh of a deer that the hunters had left for them, and dashed up a “very steep acclivity of a mountain” toward the Bitterroot Divide.

Fog in the “Hollars”

Fog at sunrise imposes a new reality on the landscape, slowly refreshing a familiar view, detail by detail, as the temperatures equalize above and below the bank, and the white veil dissolves into sunshine. This photo provides a hint of John Ordway’s view from K’useyneiskit near the east end of the ridge on that late-June morning in 1806. The “hollar” on the south side of the ridge was the Papoose Creek drainage; to the north were the sources of Cayuse Creek and Howard Creek.

In this photo, it is the Clearwater Canyon that is abrim with fog. Nearly two thousand feet beneath the bank, the Middle Fork of the Clearwater River flows swiftly northwest (upper right) toward the Snake River. To the southeast (upper left) are the grain fields of Nez Perce and Camas prairies.

The day after Meriwether Lewis left Pittsburgh on 31 August 1803, he observed the typically seasonal morning fog in the Ohio River valley, and bent his methodical mind to the challenge of explaining it. The fog, he reasoned,

appears to owe it’s orrigin to the difference of temperature between the air and water the latter at this seson being much warmer than the former; the water being heated by the summer’s sun dose not undergo so rapid a change from the absence of the sun as the air dose consequently when the air becomes most cool which is about sunrise the fogg is thickest and appears to rise from the face of the water like the steem from boiling water.[1]Lewis may have consulted Owen’s Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1764), a four-volume encyclopedia that he had brought along, from which he could have gained the basic definition for the … Continue reading

Lewis confirmed his analysis with further observations. On the morning of 4 September 1803, he reported:

Morning foggy, obliged to wait. Thermometer at 63°— temperature of the river-water 73° being a difference of ten degrees, but yesterday there was a difference of twelve degrees, so that the water must have changed it’s temperature 2d[egrees] in twenty four hours, coalder; at 1/4 past 8 the murcury rose in the open air to 68° the fogg dispeared and we set out; the difference therefore of 5° in temperature between the warter and air is not sufficient to produce the appearance of fogg—

On the sixteenth his progress was again delayed by thick fog until eight o’clock. At sunrise the temperature of the air was 54°, of the water, 72°.

If the sight from “Thirteen Mile Camp” on 29 June 1806, prompted Lewis to study this atmospheric phenomenon again, he left us no evidence of it. At least it didn’t impede their progress this morning, as it did so often on the rivers they navigated.

Rocky Point

Rocky Point, which tops out at an elevation of 6280 feet, stands well above the surrounding forest, permitting an unobstructed view of the surrounding terrain. The first permanent fire lookout here was built in 1934; it was rebuilt on a ten-foot-high concrete base in 1963. As of 2004 it had been staffed every summer since. Aerial surveillance gradually replaced permanent lookout towers such as this after about 1970, and the accuracy of GPS technology has proven still more reliable. Many lookout towers have been abandoned and dismantled, with a few preserved not only for their historic value but also for overnight rental by the U.S. Forest Service to recreationists.

The camera is aimed toward the southwest. The last mile of the road leading to the small parking area at lower left is steep, narrow, and too rough for passenger cars. The expedition approached the point from the west on the ridge that enters the photo at the upper right corner, and descended to the headwaters of the Lochsa at the lower left corner.

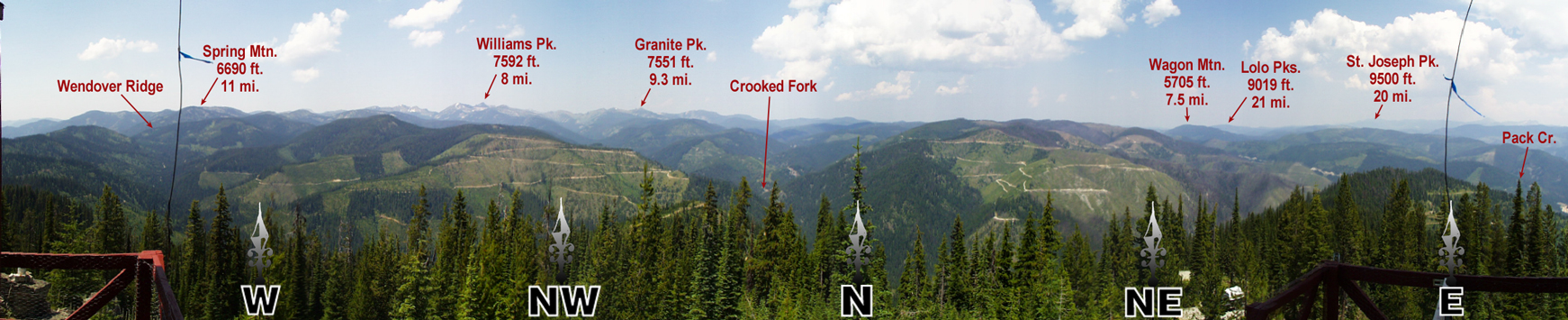

This partial (180°) panorama was shot from the north side of the lookout tower—the near right side in the aerial photo above. The apparently treeless areas have been logged and replanted, but the new growth is still too young to look like forest. The blackened area seen in the direction of Wagon Mountain, on Rascal Ridge, was burned in the summer of 2001 by the Crooked Fire. (Forest fires are given names for easy reference; this one was named after the drainage in which it occurred—Crooked Fork.) To the right of the fire scar, the two rough whiteish lines roughly beneath Lolo Peaks and St. Joseph Peak are road cuts on U.S. Highway 12, which connects Lewiston, Idaho, with Missoula, Montana.

Notes

| ↑1 | Lewis may have consulted Owen’s Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1764), a four-volume encyclopedia that he had brought along, from which he could have gained the basic definition for the time: “If the vapours, which are raised plentifully from the earth and waters, either by the solar or subterraneous heat, do, at their first entrance into the atmosphere, meet with cold enough to condense them to a considerable degree, their specific gravity is, by that means, encreased; and so they will be stopped from ascending, and return back, either in form of dew, or drizzling rain; or remain suspended some time in the form of a fog. Vapours may be seen on the high grounds as well as the low, but more especially about marshy places: they are easily dissipated by the wind, as also by the heat of the sun: they continue longest in the lowest grounds, because these places contain most moisture, and are least exposed to the action of the wind.” The understanding of the earth’s atmosphere and the development of the science of meteorology increased steadily during the early 19th century. In 1803, for example, the British meteorologist Luke Howard introduced the names of the basic cloud formations—cirrus, cumulus, stratus, nimbus, and their combinations. Lewis probably was unaware of Howard’s contribution, for he never used any of those terms in reporting the weather. |

|---|