As Lewis moves down Eldorado Creek, hungry stomachs are filled with grouse, horse beef, coyote, and crawfish. They would fare better on their return the following spring.

Spruce Grouse

Falcipennis canadensis

© 11 September 2009 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Full Stomach Camp

Lewis and his party didn’t get off the morning of 20 September 1805 until 10 o’clock because their horses had scattered during the night. The best surprise of the day was finding, only two miles from camp, “the greater part” of a stray Indian horse that Clark had killed and left for them. They “made a hearty meal on our horse beef much to the comfort of our hungry stomachs.” Immediately after dinner came a major frustration: Private Lepage’s packhorse was missing, along with some precious trade goods and all of Lewis’s winter clothing. The whole outfit stood around until three o’clock, when Lepage finally returned from an unsuccessful search. Meanwhile, Lewis evidently made good use of the down-time, taking notes on snowberry and honeysuckle bushes, mountain ash and chokecherry trees, and the large, lofty western redcedar. He observed more closely two new shrubs, mountain huckleberry and Sitka alder; three new gallinaceous birds[1]Gallinaceous birds belong to the order Galliformes. In the heirarchy of plant and animal classifications, order is the next category above family. Galliformes (gal-ih-FOR-meez) combines the Latin … Continue reading—blue grouse, spruce or Franklin grouse, and ruffed grouse—plus three new passerine birds[2]Passerines are birds of the order Passeriformes, which is a compound Latin word meaning “sparrow-shaped,” and signifying that all members of the families belonging to that order share … Continue reading—the gray jay, the Steller’s jay, and the varied thrush.

Furthermore, they didn’t see a single animal track the whole day. All they could shoot was two “pheasants,” which made a meager supper for the seven men. On reaching Cedar Creek they camped in a grove of majestic western redcedar and lofty western white pine. In one of the latter there is a faint old scar that once was said to have been Clark’s name, but was only a hoax.

Small Prairie Camp on Eldorado Creek

Clark wrote that on 15 June 1806, the Corps camped at “a Small glade of about 10 acres thickly Covered with grass and quawmash, near a large creek” which is today known as Eldorado Creek. This is the glade he meant. There is a piece of dry ground among the trees at right. The trail is just out of sight to the left. The elevation here is about 3540 feet above Mean Sea Level. —Steve Russell

Strayed horses combined with the inconvenience of a heavy rain delayed their departure from camp until 10 o’clock this morning. At Crane Meadows they came upon two deer that Reubin Field and Alexander Willard had killed and hung in a tree for them. A few miles farther up the slippery road they reached Collins (Lolo) Creek, where they found the two hunters and a third deer. They managed to cover an estimated 22 miles this dreary day, camping “near a small prarie in the bottom land” near Eldorado Creek.

Salmon Trout Camp, 1806

Eldorado Creek at Salmon Trout Camp

© 29 June 2009 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Four men worked ahead of the main party to start with, on the morning of the eighteenth, Potts “cut his leg very badly with one of the large knives.” Lewis staunched the veinous bleeding with “a little cushon of wood and and tow.”[3]Ordway reported that Lewis stitched the wound. “Tow” is a Southern word denoting a heavy, loosely-woven fabric made of “the coarse and broken parts of flax and hemp” (Webster, … Continue reading Next, John Colter‘s horse fell while trying to ford torrential Hungery Creek. Horse and rider “were driven down the creek a considerable distance rolling over each other among the rocks.” Both survived without injury, but Colter lost his blanket; we are not told whether their meager supplies held any replacements, but probably not. They made their way back to Lolo Creek, expecting to find deer to sustain them while they waited for Nez Perce guides to arrive.

From this camp the captains sent Drouillard and Shannon all the way back to the Nez Perce villages “in the plains beyond the Kooskooske” to find guides who would escort them all the way to the Great Falls of the Missouri, for the price of two guns plus a ten-horse bonus when they reached the Falls. While they waited the captains ruminated about alternatives.

On the nineteenth the hunters saw no game all day, but finally shot at some “salmon trout”—called steelhead now. That night their three Nez Perce guides set fire to some trees—probably subalpine fir, judging from Lewis’s comment that “they have a great number of dry lims dear their bodies which when set on fire creates a very suddon and immence blaze from bottom to top of those tall trees.” The result was “a beautifull object in this situation at night,” he continued. “This exhibition reminded me of a display of fireworks.” The Indians explained that their purpose was to summon fair weather for their journey. Obviously it worked. Except for a few showers and occasional clouds, twenty-eight of the next thirty days were brightened by fair skies.

Pheasant Camp on Lolo Creek

Pheasant Camp below Eldorado Creek

View north

© 6 October 2016 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Lewis’s eyes were drawn up to the crowns of some awesome stands of “Arborvita”–western redcedar (Thuja plicata Donn.)—as he followed K’useyneiskit westward out of “Full Stomach Camp” on 21 September 1805. He saw “several sticks . . . large enough to form eligant perogues of at least 45 feet in length.”[4]In this instance Lewis clearly used the word “perogue” as a synonym for “dugout canoe,” not for a large rowboat like the expedition’s own red and white pirogues. That night he and his party camped on the bank of today’s Lolo Creek, planning to make a forced march the next day to reach open country. According to Lewis: “we killed a few Pheasants, and I killd a prarie woolf[5]The “pheasants” were either blue, ruffed, or Franklin grouse. The “prarie woolf” was a coyote, Canis latrans. Sergeant Gass simply said “wolf.” The coyote, the … Continue reading which together with the ballance of our horse beef and some crawfish which we obtained in the creek enabled us to make one more hearty meal,” adding darkly, “not knowing where the next was to be found.” Like most of his men, he was steadily growing weaker from lack of adequate nourishment. All of their bodies were “much reduced.”

Idaho’s Lolo Creek

A Creek for Collins, Lolo Creek (Idaho)

View west

To see labels, point to the image.

© 2001 Airphoto, Jim Wark. All rights reserved.

The canyons cleave the deep, soft volcanic basalt until they touch bedrock. The sources of Collins Creek—called Lolo Creek since the 1860s—spring up in the mountains east of Weippe Prairie at about 5,500 feet above Mean Sea Level. The edge of the prairie at photo center is at 3,200 feet MSL; its mouth in the canyon of the Clearwater River, approximately 45 miles from its sources, is at 1,047 feet MSL. With a pause on the prairie to water the rich camas meadows, it tumbles an average ten feet per mile.

He had gotten off to a bad start. At River Dubois camp in the winter of 1804 he built an image of himself as a thief, a liar, and a drunk. He was indifferent to rules; he had little respect for authority. He was, in contemporary terms, a dodger. Captain Clark summed him up in another, equally disparaging term, blackguard (pronounced blag-gerd)—in Webster’s earliest definition (1806), “a person of foul scurrilous language.” Besides all that, he was a slow learner. He earned 50 lashes before the Corps got away from St. Charles in late May 1804, and his back could scarcely have healed before, at the end of June, he was sentenced to another 100 lashes for stealing whiskey and drinking on sentry duty. His name was Private John Collins. He had a lot to live down.

Yet the captains, or at least Clark, apparently saw something in him that was worth saving. On 8 July 1804, when he was no doubt still nursing a very sore back, they tested his mettle by assigning him duty as the Superintendent of Provisions for his squad, to be “immediately responsible to the commanding Officers for a judicious consumption” of daily provisions. He was also to cook for both of his squad’s messes. Like the other two superintendents, John Thompson and William Werner, he was exempted from pitching tents, collecting firewood, building scaffolds for drying meat. He was also excused from guard duty. The catch was, he was responsible for persuading other men in his squad to stand his tour for each of those duties. His buddies had showed him in two courts martial that they had little sympathy for him, so it was imperative for him to cultivate a new image for himself. In mid-October Clark appointed him as a member of the court martial of Private John Newman, who was charged with and convicted of insubordination and mutinous conduct, was flogged, and “discarded from the perminent party engaged for North Western discovery.” Collins may have played his role in Newman’s trial with mixed feelings, but he must have learned his lesson well.

Otherwise, John Collins apparently kept a low profile. While among the Lemhi Shoshones in late August 1805, Clark sent him on a short errand in the company of an Indian, which suggests Collins had at least gained some proficiency in Plains Sign Language. Otherwise, his name seldom came up in the journals any more, except as a hunter. By the middle of June he was comfortable enough with himself as well as his commanders and the rest of the Corps that he could indulge an off-beat but good-natured impulse. He presented Lewis and Clark with “Some verry good beer made of the Pa-shi-co-quar-mash bread” which “by being frequently wet molded & Sowered &c.” It seems that by the end of the expedition he had at least neutralized his place in its history; Lewis had no remarks to make about him in the personnel report he submitted Secretary of War Henry Dearborn.[6]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854 (2nd ed., 2 vols, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 366, 370n.

Collins must have been one of the six hunters Clark selected to accompany him on 18 September 1805, to “hurry on to the leavel country a head and there hunt and provide some provision” for the rest of the hungry crew. By the time they reached Weippe Prairie, Collins’s rehabilitation may have been complete in Clark’s mind, and the naming of a significant watercourse such as this one for John may have been a suitable token of his respect for the blackguard’s admirable recovery.

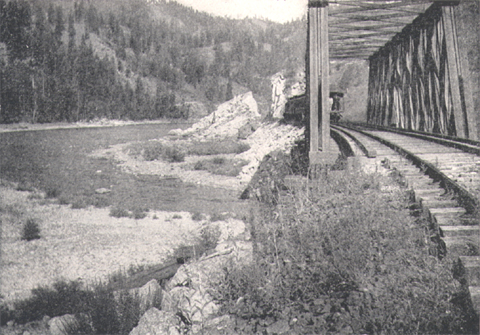

Wheeler’s Lolo Creek

Lolo Creek at the Clearwater

for Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark, plate 61. See also Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”

Within less than two decades after the close of the expedition, traveling artists began rendering their impressions of various attractions along Lewis and Clark’s route. The first writer to trace the entire route of the Lewis and Clark Expedition from St. Louis to the mouth of the Columbia and back was Olin D. Wheeler, whose book, The Trail of Lewis and Clark (1904) contained 196 illustrations, more than two-thirds of which were recent photographs of places, persons, and artifacts relating to the expedition. Wheeler was a public relations specialist for the Northern Pacific Railroad, which had finished laying track through the Northwest in 1882. One of his purposes in writing the book was “to show . . . the agency of the locomotive and the steamboat in developing the vast region that Lewis and Clark made known to us.”

The Union Pacific Short Line was completed in the late 1890s to connect Lewiston, on the Snake River, with Kooskia, 75 miles up the Clearwater. In the photo, a passenger train has just crossed Lolo Creek at its confluence with the Clearwater, and is about to pass through a cut in the mountainside, en route to Lewiston.

Notes

| ↑1 | Gallinaceous birds belong to the order Galliformes. In the heirarchy of plant and animal classifications, order is the next category above family. Galliformes (gal-ih-FOR-meez) combines the Latin gallus, meaning cock or rooster, with forma, meaning form or shape. The order Galliformes consists of seven families worldwide, of which four are found in the United States. The three most familiar in northern latitudes are the Grouse Family, Pheasant Family, and Turkey Family, all of which more or less resemble domestic chickens. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Passerines are birds of the order Passeriformes, which is a compound Latin word meaning “sparrow-shaped,” and signifying that all members of the families belonging to that order share broad skeletal resemblances which were established early in their evolutionary histories. The passerines consist of 59 families and about 8,750 species of perching birds and song birds, comprising some three-fifths of all living birds. |

| ↑3 | Ordway reported that Lewis stitched the wound. “Tow” is a Southern word denoting a heavy, loosely-woven fabric made of “the coarse and broken parts of flax and hemp” (Webster, 1806). It was used to make large containers called tow sacks, or gunnysacks, to carry farm and plantation produce. |

| ↑4 | In this instance Lewis clearly used the word “perogue” as a synonym for “dugout canoe,” not for a large rowboat like the expedition’s own red and white pirogues. |

| ↑5 | The “pheasants” were either blue, ruffed, or Franklin grouse. The “prarie woolf” was a coyote, Canis latrans. Sergeant Gass simply said “wolf.” The coyote, the grouse and the crawfish altogether would have made little more than a modest offering of hors d’oeuvres for Lewis and the other 25 adults in his party. A mature coyote weighs in at somewhere between 20 and 40 pounds, bones and all. |

| ↑6 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854 (2nd ed., 2 vols, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 366, 370n. |