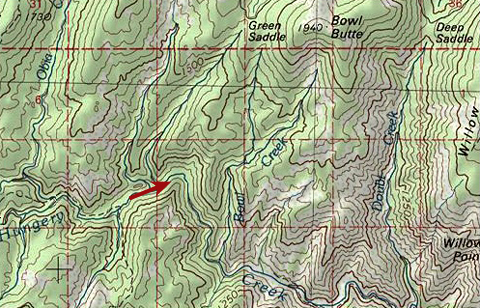

The Indians’ assurance they could cross the mountains in six days was false. The prediction they would find no game there was all too true. Clark named this part of the Road to the Buffalo “Hungery Creek” with good reason.

Lewis’s “Dry Camp”

By the evening of 17 September 1805, their seventh sleep west of Travelers’ Rest, it was obvious to the captains that the Indians’ assurance that they could cross the mountains in six days was false, whereas the prediction that they would find no game there was all too true. After they breakfasted on leftover colt meat the next morning, therefore, Clark took six hunters and pushed on ahead toward the “leavel country” where they hoped to be able to shoot some game. Lewis followed with the main party making 18 difficult, thirsty miles for the day, and camping on a steep ridge somewhere west of Bald Mountain, with the only water to be found was “in a steep raviene about 1/2 mile from . . . camp.” Their noon and evening fare consisted of “a skant proportion of portable soupe” which, except for some rendered bearfat and about 20 pounds of tallow candles, was all they had left in their larder, their best recourse being, as Lewis insinuated, to shoot a packhorse. Otherwise, their guns were “but a poor dependance in our present situation where there is othing upon earth exept ourselves and a few small pheasants, small grey Squirrels, and a blue bird of the vulter kind about the size of a turtle dove or jay bird”—the last being a Stellar’s jay, perhaps.

Clark’s “Hungery Camp”

Hungery and Obia Creek Confluence

© 2008 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Obia Creek, out of frame, enters on the left and just behind the camera’s vantage point.

Dire circumstances demanded extreme measures. Clark wrote some time later—perhaps in 1810 for the information of Nicholas Biddle, the man he had then hired to edit the journals—that

The want of provisions together with the dificuely of passing those emence mountains dampened the spirits of the party which induced us to resort to Some plan of reviving ther Sperits. I deturmined to take a party of the hunters and proceed on in advance to Some leavel Country, where there was game, kill some meat & Send it back, &c.

On 18 September 1805, accompanied by six hunters chosen from the dozen or so the Corps normally relied on, he sprinted ahead for an estimated 32 miles this day, a forced march under the best of conditions, but for those men a grueling scramble through a labyrinth of fallen timber, with a pause of only an hour at a rare grassy spot to let the horses eat and rest. The hunters, who were most likely spread out a half-mile or more on either side of the trail, found some signs of deer—perhaps hoof-prints, droppings, or else brush trimmed or “hedged” by browsing—but saw nothing to shoot at. Toward the end of the day they arrived at “a bold running Creek passing to the left,” which Clark named “Hungery Creek as at that place we had nothing to eate.”

The stream they camped beside was called Obia Creek later in the 19th century, probably after a miner by that name. It was replaced with Clark’s choice sometime after 1950 on the recommendation of Clearwater National Forest supervisor Ralph Space, and by authority of the U.S. Board on Geographic Names. The miner’s name was transferred to a tributary that begins on the flank of Bowl Butte.[1]The person responsible for the restoration of the name and spelling, “Hungery Creek,” was Ralph S. Space, who was supervisor of the Clearwater National Forest from 1954 to 1963. Beginning … Continue reading Clark’s name, including his logical but deviant spelling of the adjective—he also spelled it “hungary”; Lewis usually spelled it “hungry”—is one of the few remaining mementos of the Corps’ journey through the Bitterroot Mountains.

The extreme rigor of the day’s travel was relieved for Lewis only by the thrill of discovering, from a high point on the ridge—possibly today’s Sherman Peak—”an emence Plain and leavel Countrey to the S W. & West at a great distance.” The welcome glimpse of this country, “our only hope for subsistance,” wrote Lewis, “greately revived the sperits of the party already reduced and much weakened for the want of food.” He had seen the eastern margin of the vast, rich region that within a few more decades would begin to be known as the Great Columbia Plain.[2]Donald W. Meinig, The Great Columbia Plain: A Historical Geography, 1805-1910 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1968), 45-47.

Portable Soup Camp

Old Indian Trail above Obia Creek

© 2008 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The original Northern Nez Perce Trail, wide and roundly eroded, can just be made out under the fallen trees and brush. Here the trail climbs to a saddle between Obia Creek and Horsesteak Meadow to avoid a steep canyon on Hungery Creek.

After a march of only six miles “S. 20 W.” from “Dry Camp,” Lewis and his party of 25 arrived at the same summit early on the morning of the nineteenth. Resorting again to the language chain for communication with Toby, he was given to understand that “through that plain . . . the Columbia river, in which we were in surch[,] run.” Lewis estimated the plain was about 60 miles away, which was more or less correct, but he also understood Toby to say they would reach its borders the next day. In fact, they were both probably looking at Camas Prairie and Nez Perce Prairie, which are west and south of the Clearwater River, which the Corps as a whole would not set foot on until their return trip eight months later. Furthermore, the Columbia River at its nearest is 175 straight-line miles west of Sherman Peak. Including the ten days it would take to carve six dugout canoes, the Columbia was four weeks away. Nonetheless, Lewis allowed himself some satisfaction, for “the appearance of this country, our only hope for subsistance greately revived the sperits of the party already reduced and much weakened for the want of food.” (see Short rations.)

Quickly but laboriously they descended into the valley of Hungery Creek, where “the road was excessively dangerous . . . being a narrow rockey path generally on the side of steep precipice.” Indeed, Frazer’s pack horse lost his footing on it that afternoon, and took a hundred-yard tumble with his load roped to his back for “near a hundred yards into the Creek,” over “large irregular and broken rocks.” Miraculously, the horse survived, and so did the precious pack.

At the end of an 18-mile day, they “took a small quantity of portable soup, and retired to rest much fatiegued.”

Horsesteak Meadow

Clark and his advance detail of six hunters camped here on 18 September 1805. Lewis and the main party passed through three days later. The fairly large meadow, which is seen in the center of the aerial photo below, is dry most of the year. Hungery Creek is just beyond the trees at right. The original trail tread is very faint here because of the rocky soil, and because of occasional flooding during spring runoff. —Steve Russell

On their return, this was their rest and fast-food-for-the-horses stop for Monday the 16 June 1806. Here, they found:

a handsome little glade in which we found some grass for our horses we therefore halted to let them graize and took dinner knowing that there was no other convenient situation for that purpose short of the glaids on hungry creek where we intended to encamp, as the last probable place, at which we shall find a sufficient quantity of grass for many days.

That morning they “saw in the hollows and N[orth] hillsides large quatities of snow yet undisolved; in some places it was from two to three feet deep.”

Short Rations

Portable Soup

© 2010 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The Corps of Discovery had been on short rations ever since leaving the Great Falls of the Missouri. Back on 13 July 1805, as he prepared to strike camp on White Bear Island and headed toward the Rocky Mountains, Lewis remarked that the company normally consumed “an emensity of meat.” It required, he said, “4 deer, an Elk and a deer, or one buffaloe, to supply us plentifully 24 hours.” In modern nutritional terms, each man probably was burning up to 7,000 calories per day, two or three times as many as an average active person today, and even more than a collegiate tackle’s 5,000-calorie daily requirement during football season. In ordinary 21st-century terms, every day each of the party could have eaten two Monster Thickburgers with medium fries and a large pop, for a total of 2,340 calories per meal, and still not gained any weight.

Back at Fort Mandan, Sheheke (Big White) of the Mandans had warned them that game would be scarce in the mountains. His prediction came true within days after leaving White Bear Islands on 15 July 1805. By the last day of July they were out of fresh meat. They had counted on their remaining flour, parched meal, and corn to sustain them until they got across the Rockies, but all that was gone by the first week in September, back in Lemhi Shoshone country on the Salmon River. Naturally, the men took to the usual soldierly complaint about the food. Clark observed sympathetically on 27 August 1805: “my party hourly Complaining of their retched Situation and [contemplating?] doubts of Starveing in a Countrey where no game of any kind except a fiew fish can be found.” The reality of K’useyneiskit, which would be practically meatless and altogether fishless, was still ahead of them.

Once they entered the mountains, the demands of their daily labors on their bodies increased while the food supply declined. By the old standards, in the 72 days between the day they left White Bear Islands on the upper Missouri until 7 October 1805, when they left Canoe Camp on the Clearwater River, they had appetites equal to 288 deer, or 72 deer plus 72 elk (there were no bison at all west of the Falls of the Missouri). But the only red meat the 33 souls plus one dog tasted in those ten weeks came from 80 deer, 12 elk, eight antelope, two colts and two horses, a total of 104 four-legged animals, plus assorted waterfowl and grouse—a little over one-third of their normal needs. And what of Sacagawea and her seven-month-old baby? Which of those young men might have offered to share their meager provender with a teen-age mother who was eating for two?

Worst of all, between the day they left camp at Travelers’ Rest on the Bitterroot River and the day they reached Weippe Prairie, a total of 12 days during which the work load rose and temperatures dropped, they barely survived on two colts and a horse and some portable soup They were beyond the futility of mere complaining. Full rations would have amounted to 48 deer, but they saw only four—on the sixteenth. Near camp that morning Clark snapped the lock of his rifle seven times at a large mule deer buck before he realized the flint was too loose to ignite the powder in the pan. Think of the crescendo of frustration and disappointment among the hungry witnesses as that deer remained within shooting range long enough for seven tries.

Jerusalem Artichoke Camp

A minor crisis marred this morning when one of the Nez Perce guides “complained of being unwell, a symptom which I did not much like as such complaints with an indian is generally the prelude to his abandoning any enterprize with which he is not well pleased.” As an officer, Lewis was not accustomed to tolerating any such excuses from the men under his command, but he reluctantly proceeded on after the guides promised to catch up later. His fears proved unfounded in this instance. “The indians continued with us,” he later reported with relief, “and I beleive are disposed to be faithfull to their engagement.” In fact, at the end of the day he responded with sympathetic understanding. “I gave the sik indian a buffaloe robe he having no other covering except his mockersons and a dressed Elkskin without the hair.”

Meanwhile, at about midday, Sacagawea had brought him “a small knob root a good deel in flavor an consistency like the Jerusalem Artichoke.” He recognized it as a species not previously known to botanists, but which was soon to gain a name befitting its simple makeup and delicate flower—western spring beauty.

Cache Mountain, 1806

On the 17 June 1806 conditions grew more daunting by the mile. The Corps started down Hungery Creek, having to cross it several times, and finding it “difficult and dangerous to pass . . . in consequence of its debth and rapidity.” They “avoided two other passes of the creek by ascending a very steep rock and difficult hill,” and eventually climbed the mountain “to the hight of the main leading ridges which divides the Waters of the Chopunnish and Kooskooske rivers.” A few miles farther on they found themselves “invellped in snow from 12 to 15 feet deep even on the south sides of the hills with the fairest exposure to the sun.” Here, declared Lewis, was “winter with all it’s rigors.”

They knew it would take five days to reach their campsite of 14 September 1805, even if they were able to stay on the right ridges, and of that their chief woodsman and guide, George Drouillard, was “entirely doubtfull.” Besides, until they reached that point there would be no grass for the horses nor firewood for the people because of the deep snow. “If we proceeded and should get bewildered in these mountains,” they all agreed, “the certainty was that we should loose all our horses and consequently our baggage instruments perhaps our papers and thus eminently wrisk the loss of the discoveries which we had already made if we should be so fortunate as to escape with life.” In other words, the key factor was the welfare of the horses. Yet, if they waited for the snow to melt enough for them to follow the Indian road with assurance, they might not get home before the end of the travel season. The choice was obvious but painful to admit. They would have to retreat to a place where they could keep the horses well fed until they could procure a reliable Nez Perce guide.

“Having come to this resolution,” wrote Lewis, “we ordered the party to make a deposit for all the baggage which we had not immediate use for, and also all the roots and bread of cows [cous] which they had except an allowance for a few days to enable them to return to some place wt which [they] could subsist by hunting untill we procured a guide.” The captains left their instruments papers &c,” believing them to be safer there than to risk them on horseback over the roads and creeks they had had to retrace and re-cross. “Our baggage being laid on scaffoalds and well covered we began our retrograde march at 1 P. M. having remained about 3 hours on this snowy mountain.”

“The party were a good deel dejected tho’ not so as I had apprehended they would have been,” Lewis wrote. “This is the first time since we have been on this long tour that we have ever been compelled to retreat or make a retrograde march.”

Greensward Camp

Spring was coming late to the ridges and north-facing slopes along K’useyneiskit, it seemed, but there were encouraging signs of its inevitable approach. Leaving “Jerusalem Artichoke Camp” at 6:00 a.m. on 26 June 1806, they soon reached the cache of supplies they had left on a ridge on 17 June (Cache Mountain). There they found that the snow depth had diminished nearly four feet in the intervening nine days. Near “the border of the snowey region” they shot three “pheasants” [grouse]. After a two-hour stop to rearrange the loads on their pack horses, they proceeded on along the high, dry ridge under the urging ot their Nez Perce guides, who warned that the next suitable campsite was a considerable distance away. Lewis was relieved when:

late in the evening much to the satisfaction of ourselves and the comfort of our horses we arrived at the desired spot and encamped on the steep side of a mountain convenient to a good spring. here we found an abundance of fine grass for our horses. this situation was the side of an untimbered mountain with a fair southern aspect where the snows from appearance had been desolved about 10 days. the grass was young and tender of course and had much the appearance of the greensward.

To eastern landowners like Lewis and Clark, a “greensward” was a pleasant, naturally grassy turf or meadow. Lewis continued:

there is a great abundance of a speceis of bear-grass which grows on every part of these mountains its growth is luxouriant and continues green all winter but the horses will not eat it.

Soon after camp was pitched another Nez Perce man appeared in the firelight. He had been pursuing the party under the desire to accompany them to the Falls of the Missouri. Lewis continues:

We were now informed that the two young men whom we met on the 21st and detained several days are going on a party of pleasure mearly to the Oote-lash-shoots or as they call them Sha-lees, a band of the Tush-she-pah nation who reside on Clark’s river in the neighbourhood of traveller’s rest.

—Meriwether Lewis, 16 June 1806

The Tush-she-pahs were the Salish Indians, known to the Shoshones, as tatasiba, or “the people with shaved heads,” or “Flat Heads.”[3]Moulton, 5:187-88.

Bald Mountain Panorama

360° panoramic photo

Notes

| ↑1 | The person responsible for the restoration of the name and spelling, “Hungery Creek,” was Ralph S. Space, who was supervisor of the Clearwater National Forest from 1954 to 1963. Beginning in 1924, when it was still suitable only for foot or horse traffic, Space spent more than 50 years of his life traveling and studying K’useyneiskit and its history. The road that now parallels the main Indian road, the Lolo Motorway, was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps beginning in 1934. Ralph S. Space, The Lolo Trail: A History and a Guide to the Trail of Lewis and Clark (2nd ed., Missoula: Historic Montana Publishing, 2001). The Clearwater Story: A History of the Clearwater National Forest (Orofino, Idaho: USDA Forest Service and the Clearwater Historical Society, 1979), 61-69, 230. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Donald W. Meinig, The Great Columbia Plain: A Historical Geography, 1805-1910 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1968), 45-47. |

| ↑3 | Moulton, 5:187-88. |