At Fort Clatsop on 5 February 1806, Reubin Field returned from a hunt with “a phesant which differed but little from those common to the Atlantic states; it’s brown is reather brighter and more of a redish tint. it has eighteen feathers in the tale of about six inches in length. this bird is also booted[1]A “booted” leg is a feathered leg. as low as the toes. the two tufts of long black feathers on each side of the neck most conspicuous in the male of those of the Atlantic states is also observable in every particular with this.” On the third of March Lewis added more details about the bird:

The small brown pheasant is an inhabitant of the same country and is of the size and shape of the specled pheasant which it also resembles in it’s economy and habits. the stripe above the eye in this species is scarcely perceptrable, and is when closely examined of a yellow or orrange colour instead of the vermillion of the others. it’s colour is an uniform mixture of dark and yellowish brown with a slight mixture of brownish white on the breast belley and the feathers underneath the tail. the whole compound is not unlike that of the common quail only darker. this is also booted [feathered] to the toes. the flesh of this is preferable to either of the others and that of the breast is as white as the pheasant of the Atlantic coast.

There are at least twelve—some authorities say fifteen—subspecies of Bonasa umbellus in North America that are distinguishable to experienced eyes, in details of coloration, including the prominence and color of barring on breasts and tail feathers. The specimen pictured in Figure 1 belongs to the subspecies umbelloides (um-bill-loy-deez), which was first identified by David Douglas (1799-1834) in 1829. Figure 2, which was taken in Manitoba, Canada, depicts the species B. u. incana (in-cay-nah; “hoary,” in reference to the grayish breast), which is found in southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan, as well as southeastern Idaho into central Utah and western Colorado, and isolated areas of North and South Dakota.

Altogether, the collective North American subspecies of Bonasum umbrellus occupy a huge region extending from northern Alaska and western British Columbia eastward to the Atlantic Coast of Canada, with fingers of habitat extending southward along the coast of Washington and Oregon; another finger straddling the Northern Rockies as far south as northern Utah; another branch descending into Minnesota and southern Wisconsin; and yet another reaching southwestward from Nova Scotia through New England along the Appalachians to the northern boundary of Alabama and Mississippi.[2]“Index of Species Information” for Bonasa umbellus, at http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/animals/ (accessed 18 November 2010).

Classification

Linnaeus—or one of his informants—imagined that the glossy black feathers on the sides of a male grouse’s neck (discreetly hidden in repose, as on the grouse in Figure 1) which were erected during the courting display, resembled an umbrella, and so the Latin cognate umbellus (um-bell-us) seemed perfectly suitable as a specific epithet. Except for the difference in color, however, the grouse’s showy collar more closely resembles the starched white, pleated ruffle neckpieces, called “ruffs,” that framed the faces of well-dressed ladies and gentlemen during the reigns of Elizabeth and James I. Indeed, it is from that rarely seen high collar of black feathers that the “king of upland game birds” gained its most appropriate, because most descriptive, common name.[3]The author confesses that he hunted upland game birds in western Montana for many years, never once seeing a ruffed grouse in full display, and thus having no inkling of the reason for the … Continue reading

In 1825 the Irish zoologist Nicholas Aylward Vigor (1785-1840) classified the ruffed grouse in the family Tetraonidae (tet-rah-on-ih-dye); the term is a form of the Greek noun for grouse, tetraon. It has since been re-classified in the sub-family Tetraoninae of the family Phasianidae (pheasants). The name grouse is believed to have evolved from some form of the French word greoche, meaning “spotted bird.”[4]John K. Terres, The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds (New York: Wings Books, 1980), 449. The modern French common name as listed in The American Ornithologists’ Union is … Continue reading So far, so good.

Carl Linnaeus[5]Technically, his last name is Linnæus, but the web-friendly Linnaeus is used on this page. had already classified the ruffed grouse under the genus Bonasa (bon-ay-sah) in 1766, for the reason that its so-called Drumming Display climaxed with a sound that was said—when or by whom is no longer clear—to resemble from a distance the bellow of the wild ox of India, which Aristotle (384-322 BC) had identified as the bonasus, or bonasum—although Georges Buffon (1707-1788) claimed that the name was obscure even in Aristotle’s day.[6]Barr’s Buffon, 8:20-21; Google Books. The English printer James Smith Barr (fl. 1769-1806) translated and published the Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière, by Georges Louis … Continue reading Several 19th-century ornithologists tried to rename the genus, but Linnaeus’s choice prevailed on the basis of priority.

The sound of the male ruffed grouse’s “drumming” is in fact produced by a rapid beating of wings that sounds to the susceptible imagination somewhat like drumming. However, the wings do not touch any object in the manner of drumsticks, but simply beat the air to and fro rapidly enough to set the air beneath them in motion, resulting in a low-frequency rumble—approximately 60 cps. The whole recital lasts less than 10 seconds overall.[7]The pitch is in the crack on the piano keyboard between B and B-flat two octaves below Middle C. Coincidentally, 60 cps is also the frequency of household alternating current, which is sometimes … Continue reading

That electrifying sound of the forest’s “mystic drum” was transliterated long ago as “Biff—biff—biff—biff—biff” at a rapidly increasing tempo, climaxing with a muffled “burr-urr-r-r-r-r.” The exercise is repeated every few minutes for an indeterminate period of time.[8]Ed. W. Sandys, “Rod and Gun,” Outing, an Illustrated Monthly Magazine of Recreation, 32:6 (September 1898), 39:1 (7 July 1892), American Periodicals Series Online. See also—and hear— … Continue reading It is performed by males only—not necessarily in the full display mode—throughout the year but especially in spring, either to announce their presence to females and fellow males, or as a means of defining the drummer’s territories. It is typically staged on some low elevation such as a fallen log, a low tree stump, or a boulder (as in Figures 1, 2).

The ruffed grouse possesses a relatively primitive vocal apparatus. When alarmed, both males and females utter staccato quit-quit signals before taking flight. Females may sound a loud squeal or whine when surprised with her chicks, and may display a “crippled-bird” act to divert predators from them.

“Pheasant of the Atlantic states”

Figure 3 is “the Partridge of the eastern states, and the Pheasant of Pennsylvania, and the southern districts,” wrote Alexander Wilson (1766-1813) in American Ornithology.[9]Alexander Wilson, American Ornithology, or The Natural History of the Birds of the United States, 9 vols. (New York: Collins, 1828-29), 3:18. This was a reprint of Wilson’s original American … Continue reading Wilson’s vivid description of the species went beyond the mere enumerations of facts published most of his contemporaries, such as Thomas Say. With just a hint of amusement, Wilson included a hunter’s perspective on the species:

The Pheasant generally springs within a few yards [of the hunter], with a loud whirring noise, and flies with great vigour through the woods, beyond reach of view, before it alights. With a good dog however, they are easily found; and at some times exhibit a singular degree of infatuation, by looking down, from the branches where they sit, on the dog below, who, the more noise he keeps up, seems the more to confuse and stupify them, so that they may be shot down, one by one, till the whole are killed, without attempting to fly off. In such cases, those on the lower limbs must be taken first, for should the upper ones be first killed, in their fall they alarm those below, who immediately fly off.

At top speed, ruffed grouse have been clocked at 40 m.p.h. as they disappear into dense brush.[10]Terres, 451.

Wilson’s American Ornithology

Prior to Alexander Wilson’s publication of his nine-volume American Ornithology (1808-1814), the only documentations of birds in the United States were some catalogs of selected names. Among them was Jefferson’s list of 109 species that appeared in his Notes on the State of Virginia in 1787. Next came William Bartram’s Travels Through North and South Carolina, of 1791, containing the names of 215 species. Shorter lists accompanied lesser works, including Benjamin Smith Barton‘s brief Fragments of the Natural History of Pennsylvania in 1799.

Wilson’s work, which established him by general acclaim as the “father of American ornithology,” included 315 hand-colored drawings of birds, plus brief essays on 293 of them. For example, Wilson described the plight of the eastern ruffed grouse, which—locally at least—had already become what would today be classed as a “threatened species.”

Formerly they were numerous in the immediate vicinity of Philadelphia; but as the woods were cleared, and population increased, they retreated to the interior. At present there are very few to be found within several miles of the city, and those only singly, in the most solitary and retired woody recesses.

Great numbers of these birds are brought to our markets, at all times during fall and winter, some of which are brought from a distance of more than a hundred miles, and have been probably dead a week or two, unpicked and undrawn, before they are purchased for the table. Regulations prohibiting them from being brought to market, unless picked and drawn, would very probably be a sufficient security from all danger. At these inclement seasons, however, they are generally lean and dry, and indeed at all times their flesh is far inferior to that of the Qual, or of the Pinnated Grous. They are usually sold in Philadelphia market at from three quarters of a dollar to a dollar and a quarter a pair, and sometimes higher.[11]Clark Hunter, ed., The Life and Letters of Alexander Wilson (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1983), 3.

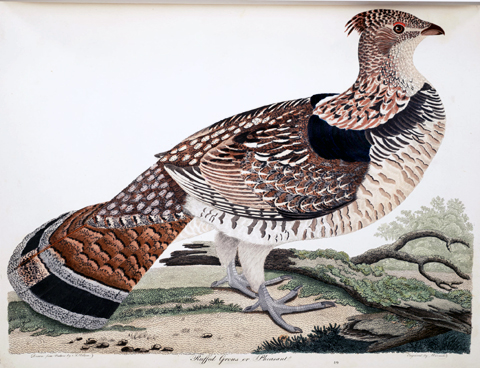

Four of the portraits were included at Lewis’s personal request, being of specimens he had brought back from the West: Lewis’s woodpecker, Clark’s nutcracker, western tanager, and black-billed magpie. His drawing of the eastern “Ruffed Grous or Pheasant,” engraved for printing by John G. Warnicke, appeared as Plate 49 in Volume Six.

Thomas Say’s Tetrao obscurus

It is instructive to compare Lewis’s description of the ruffed grouse with the scientific description written by Thomas Say in 1819. For his part, Lewis not only was a newcomer to the science of ornithology but also faced many other demands on his time and attention during the expedition. Say devoted his whole life to the natural sciences, and as a member of Stephen Long’s expedition in 1819-20[12]Edwin James, compiler, Account of An Expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains Performed in the Years 1819 and ’20 . . . under the command of Stephen H. Long (2 vols., Philadelphia: H. … Continue reading was expected to focus his attention on plants and animals, bringing to bear his education and experience in the application of the Linnæan system of classification.

Say carried a copy of Nicholas Biddle‘s edition of the captains’ journals. Biddle’s paraphrase of Lewis’s description of the ruffed grouse, which contained enough ambiguities to spawn vigorous debate as to which one of the three he really meant, reads as follows:

The small brown pheasant is an inhabitant of the same country,[13]That is, “that portion of the Rocky Mountain watered by the Columbia river.” Lewis, 23 March 1806. and is of the same size and shape as the speckled pheasant,[14]The reference is to Lewis’s description of what was probably a female spruce grouse, and not a separate species. which he likewise resembles in his habits. The stripe above the eye in this species is scarcely perceptible; it is, when closely examined, of a yellow or orange color, instead of the vermilion of the other species. The color is a uniform mixture of dark yellowish-brown with a slight aspersion of brownish-white on the breast, belly, and feathers underneath the tail; the whole appearanhce has much the resemblance of the common quail. This bird is also booted to the toes. The flesh of this is preferable to the other two.

That bird, which Lewis had described in his own words as a “brown and yellow species,” is known today as Dendragapus obscurus (Say). Say’s description is more precisely detailed, while acknowledging his indebtedness to Lewis and Clark:

A female bird was shot on the mountain which closely resembles, both in size and figure, the females of the black game (Tetrao tetrix).[15]The genus Tetrao was named in Linnaeus’s taxonomy. It is still valid in Great Britain and Continental Europe, but no members of that genus have been identified in North America. All three of … Continue reading It is, however, of a darker colour, and the plumage is not so much banded, the tail also seems rather longer, and the feathers of it do not exhibit any tendency to curve outward, which, if we mistake not, is exhibited by the inner feathers of the tail of the corresponding sex of the black game.

Its general colour is a black-brown, with narrow bars of pale ocraceous [orange-yellow]; plumage near the base of the beak above tinged with ferruginous [rust-colored]; each feather on the head with a single band and slight tip; those of the neck, back, tail-coverts [small feathers over tail], and breast, two bands and tip; the tips on the upper part of the back and on the tail-coverts are broad and spotted with black, with the inferior band often obsolete [vestigal, imperfectly developed]; the throat and inferior portion of the upper sides of the neck are covered with whitish feathers, on each side of which is a black band or spot; a white band on each feather of the breast, becoming broader on those nearer the belly; on the belly the plumage is dull cinereous [ash-colored] with concealed white lines on the shafts; the wing coverts and scapulars [shoulder feathers], about two-banded with a spotted tip and second band, and with the tip of the shaft white; the primaries [toward end of wing] and secondaries [inner portion of wing] have whitish zig-zag spots on their outer webs, the first feather of the former short, the second longer, the third, fourth, and fifth equal, longest; feathers of the sides with two or three bands and white spot at the tip of the shaft; inferior [under] tail coverts white with a black band and base, and slightly tinged with ocraceous on their centres; legs feathered to the toes, and with the thighs pale, undulated with dusky; tail rounded, with broad terminal band of cinereous, on which are black zig-zag spots; on the intermediate feathers are several ocraeous spotted bands, but these become obsolete and confined to the exterior webs on the lateral feathers, until they are hardly perceptible on the exterior pair; a naked space above and beneath the eyes. It may be distinguished by the name of the dusky grouse (Tetrao obscurus).

When this bird flew it uttered a cackling note a little like that of the domestic fowl: this note was noticed by Lewis and Clark in the bird which they speak of under the name of the cock of the plains [the sage grouse], and to which Mr. Ord [botanist George Ord (1781-1866)] has applied the name of Tetrao fusca, a bird which, agreeably to their description, appears to be different from this, having the legs only half booted: the “fleshy protuberance about the base of the upper chop,” and “the long point tail” of that bird may possibly be sexual distinctions.

It appears by the observations of Lewis and Clark that several species of this genus inhabit the country which they traversed, particularly in this elevated range of mountains from whence, amongst other interesting animals, they brought to Philadelphia a specimen of the spotted grouse (T. canadensis [spruce grouse]) which, together with the above described bird, are now preserved in the Philadephia Museum, thus proving that the spotted grouse is an inhabitant of a portion of the territory of the United States.

Lewis used the word grouse only in reference to the sage grouse (Centrocercus europhasianus) and the sharp-tailed grouse (formerly Pediocetes phasianellus, now Tympanuchus phasianellus), and not in connection with the three new “pheasants” he found along K’useneiskit—The Road to the Buffalo or Lolo Trail. His “brown and yellow speceis,” which Say named Tetrao obscurus is now Bonasa umbellus.

Notes

| ↑1 | A “booted” leg is a feathered leg. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Index of Species Information” for Bonasa umbellus, at http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/animals/ (accessed 18 November 2010). |

| ↑3 | The author confesses that he hunted upland game birds in western Montana for many years, never once seeing a ruffed grouse in full display, and thus having no inkling of the reason for the bird’s name. |

| ↑4 | John K. Terres, The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds (New York: Wings Books, 1980), 449. The modern French common name as listed in The American Ornithologists’ Union is Gélinotte huppée, which means “crested grouse.” |

| ↑5 | Technically, his last name is Linnæus, but the web-friendly Linnaeus is used on this page. |

| ↑6 | Barr’s Buffon, 8:20-21; Google Books. The English printer James Smith Barr (fl. 1769-1806) translated and published the Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière, by Georges Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon, 36 vols. (1749–1788). |

| ↑7 | The pitch is in the crack on the piano keyboard between B and B-flat two octaves below Middle C. Coincidentally, 60 cps is also the frequency of household alternating current, which is sometimes audible in the vicinity of a light bulb or an electric motor. |

| ↑8 | Ed. W. Sandys, “Rod and Gun,” Outing, an Illustrated Monthly Magazine of Recreation, 32:6 (September 1898), 39:1 (7 July 1892), American Periodicals Series Online. See also—and hear— at http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Ruffed_Grouse/sounds. |

| ↑9 | Alexander Wilson, American Ornithology, or The Natural History of the Birds of the United States, 9 vols. (New York: Collins, 1828-29), 3:18. This was a reprint of Wilson’s original American Ornithology . . . with a sketch of the author’s life by George Ord (1806-09). Wilson’s work was later reprinted in three volumes (1828-29) by his friend and biographer, George Ord (1781-1863). Ord (1781-1866) was a member of the American Philosophical Society, and president of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia from 1851 until 1858. Wilson died of acute dysentery in 1813, at the age of 47. Wilson was also a poet, patriot, and a patriotic-song writer. He wrote the poem “Jefferson and Liberty” in 1804 for use as a campaign song. Sung to a Scottish tune known as “Willie was a wanton wag,” it was an instant hit. In 1811 he made a pilgrimage to Lewis’s grave on the Natchez Trace, where he interviewed Mrs. Grinder, the proprietor of the roadside inn where the star-crossed explorer spent his final hours. Wilson’s report was intended only for the edification of a few of his friends, but it was soon published in the leading Philadelphia literary magazine, The Port Folio, and quickly became headline news nationwide. Subsequently, rumors of a murder conspiracy began to take root, with accusations recklessly cast about, and to the present day they persist in propagating themselves. |

| ↑10 | Terres, 451. |

| ↑11 | Clark Hunter, ed., The Life and Letters of Alexander Wilson (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1983), 3. |

| ↑12 | Edwin James, compiler, Account of An Expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains Performed in the Years 1819 and ’20 . . . under the command of Stephen H. Long (2 vols., Philadelphia: H. C. Carey, 1823), 1:14-15n. |

| ↑13 | That is, “that portion of the Rocky Mountain watered by the Columbia river.” Lewis, 23 March 1806. |

| ↑14 | The reference is to Lewis’s description of what was probably a female spruce grouse, and not a separate species. |

| ↑15 | The genus Tetrao was named in Linnaeus’s taxonomy. It is still valid in Great Britain and Continental Europe, but no members of that genus have been identified in North America. All three of Lewis’s “phesants” belong to the Family Tetraoninae, meaning “black game-bird.” |