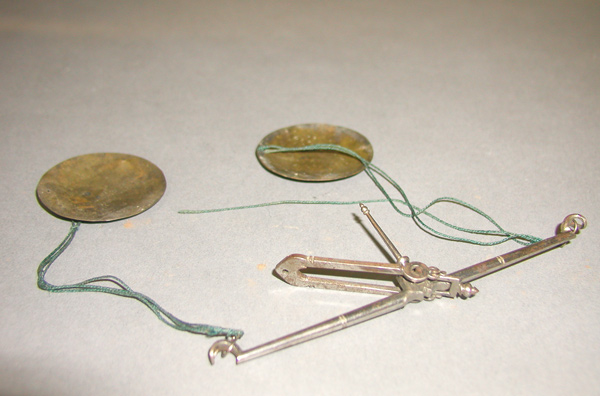

Physicians in Rush’s day mixed proportions of medicines to suit the patient’s symptoms, using apothecary scales like these.

William Cullen’s Ideas

Any study of early 18th-century American medicine will involve Benjamin Rush. Not only did he make important contributions to medicine and provide direct instructions for Lewis, he is also considered the father of psychiatry in America because of his Medical Inquiries and Observations upon the Diseases of the Mind (1812), the first book on mental diseases published in the United States. Rush may be best known, however, for his advocacy of “heroic therapeutics,” a treatment that involved much purging and bloodletting.

As stated elsewhere [see Benjamin Rush, M.D.], William Cullen’s ideas had a great effect on Rush in medical school and his beginning practice. Cullen was a solidist, believed in limited bloodletting, purging, and vomiting, and that moderation and balance were the keys to successful treatment.[1]Christopher Clayson, “William Cullen in Eighteenth Century Medicine.” In William Cullen and the Eighteenth Century Medical World, A. Doig, et al., eds., Edinburgh, Edinburgh University … Continue reading Among the factors Cullen said caused fevers were strong emotion and intemperance. Fevers could also arise from remote causes: contagions coming from other people with the disease and miasmata from such places as marshes (that is, non-human sources). Only attacking the debility caused by the disease or hygenic preventive measures were possible.

Cullen believed in disease entities (which is not to say he understood the germ theory). Thus, he compiled an extensive nosology—a classification system for diseases.[2]Lester King, The Medical World of the Eighteenth Century (Chicago University Press, 1958), 139-142. Also, Cullen expected that morbid anatomy (linking post-mortem conditions with clinical histories) as practiced by the great Giovanni Morgagni (1682-1771) would help in disease identification.[3]Richard H. Shryock, Medicine and Society in America: 1660-1860 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1972), 68.

One aspect of Cullen’s theory that survived in Rush’s mature ideas was the belief that miasmata had a role in disease (for Rush, as a predisposing cause). Also Rush maintained an essentially solidist orientation in his concepts; however, as his career progressed, he largely broke from Cullen’s ideas.

John Brown’s Theories

The most important writer among those who spurred Rush’s break with Cullenism was John Brown. Brown dismissed any notion of diseases as separate entities and classification schemes useless. He thought pathological anatomy showed only changeable forms of the disease and not the underlying cause.

Brown postulated the fundamental biologic principle of excitability. All living matter had it. Excitability was “a capacity to perceive impressions and be able to respond to them.”[4]Günther Risse, “The Brownian System of Medicine: Its Theoretical and Practical Implications,” Clio Medica, vol. 5, 1970, 45. External stimuli act upon excitability, and the combined response of stimuli and excitability is called excitement. Predisposition to disease (the state before the occurrence of disease) occurs when there are too many stimuli, causing excitability to decrease, or too few stimuli, causing excitability to increase. Excessive stimulation is called the sthenic state. Sthenic disease occurs when an overabundance of stimuli dangerously exhausts excitability, thereby creating an overabundance of excitement. This pathological state is called indirect debility. Deficient stimulation is called the asthenic state. Asthenic disease occurs when a deficiency of stimuli reduces excitement and results in “an accumulation of unused excitability.”[5]Ibid., 46. This pathological state is called direct debility.

The Brunonian system has several consequences for the practitioner. One is that a physician is responsible for the general health of a patient as well as for restoring equilibrium between excitability and outside stimuli. A second consequence is that it is only minimally necessary to distinguish precipitating—also called proximate—causes of disease. Only the general predisposing factors are important for the practitioner to determine.[6]Ibid.

Another consequence is that the practitioner doesn’t need to be concerned with specific diagnoses, for clinical history or signs of disease. As Risse has written, for the Brunonian physician, “there is but one general disease with a variety of forms, and one general pathological condition resulting from excessive or deficient excitement.”[7]Ibid., 47. The physician need only take the arterial pulse (the only reliable diagnostic procedure) and determine what stimulants the patient has received prior to becoming sick in order to prescribe treatment.

Treatment itself was relatively straightforward. In sthenic diseases, the effects of stimuli need to be lessened. Acceptable therapy included gentle cathartics, a vegetarian diet, watery drinks, and bleeding “only in the most violent cases.” In asthenic diseases, excitement needs to be increased, so rich foods, liquor, camphor, and opium are used.[8]Ibid., 48.

Brown treated his gout as an asthenic disease, and as Lester King so pungently puts it, “Evidence is not at all clear that he cured himself of gout, but it is well established that he became heavily addicted to alcohol and opium.”[9]King, 143-44.

Brown’s system has at least one more modern aspect to it. He fully emphasized how the body is subject to interaction with outside stimuli, a notion in basic accord with modern ideas of, say, how an unhealthy environment or poor food choices affect our health. The key point is, however, that Brown’s therapy is seen as supporting the system rather than depleting it.

Philadelphia’s Yellow Fever

From Brown, Rush took a number of ideas, including that of excitability. At the heart of Rush’s system—as at Brown’s—is a ruthless simplification of medicine. Classifying disease is of limited importance. There is but one proximate cause of disease, so systems of classification only confuse the practitioner. Morbid anatomy is not significant either, since not all fevers share the same phenomena and “could not be essential to fevers as such.” For instance, the intestinal lesions of typhoid fever would have been for Rush the result of vascular tension rather than, as we see them today, a basic condition of the disease.[10]Richard H. Shryock, Medicine and Society in America: 1660-1860 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1972), 70. Rush, however, based his therapy on depletive rather than supportive treatments. Also, Rush postulated one disease state as opposed to Brown’s two.

While Rush developed his theory over many years, a pivotal moment occurred during the yellow fever epidemic of 1793, one of the greatest medical disasters ever to strike America, claiming 5,000 lives (Philadelphia had a population of 55,000).

The letters Rush wrote to his wife during the epidemic detail his work, his frame of mind, the conditions of the city, and what he saw as the success of his “cure.” They discuss the afflicted and the dead, people Mrs. Rush would know. Two quotations will give some sense of the terrible consequences of the fever and Rush’s efforts. From September 1:

Thirty-eight persons have died in eleven families in nine days in Water Street, and many more in different parts of the city . . . . It is indeed truly affecting to see a solitary corpse, on the shafts and wheels of a chair, conducted through our streets without a single attendant in some cases, and with only 8 or 10 in any instance, and they at a small distance from it on the foot pavement.[11]Lyman H. Butterfield, ed., Letters of Benjamin Rush. 2 vols. (Princeton: University Press, 1951), 646.

From September 10:

Hereafter my name should be Shadrach, Meshach, or Abenego, for I am sure the preservation of those men from death by fire was not a greater miracle than my preservation from the infection of the prevailing disorder. I have lived to see the close of another day, more awful than any I have yet seen. Forty persons it is said have been buried this day, and I have visited and prescribed for more than 100 patients. Mr. Willing is better, and Jno. Barclay is out of danger. Amidst my numerous calls to the wealthy and powerful, I do not forget the poor.[12]Ibid., 657-8.

Desperately searching for some way to cure his patients, Rush read a report by John Mitchell about the Virginia yellow fever epidemic of 1741. Mitchell declared that aggressive bleeding and purging had removed the poisoned humors, the key point being that depleting even an already-depleted patient was necessary to remove fever from the body. According to Rush, application of Mitchell’s treatment to yellow fever patients worked, and with his usual zeal Rush began to promote it.[13]J. H. Powell, Bring Out Your Dead: The Great Plague of Yellow Fever in Philadelphia in 1793 (New York: Time, 1965), 80-83.

Dr. Rush’s Medicine Chest

To see labels, point to the picture.

Mütter Museum, College of Physicians of Philadelphia

This kit held nearly all the medicines a physician would need. (Fothergills Pills, a combination of plant and mineral laxatives, were similar in therapeutic use to Rush’s famous calomel-and-jalap pills.)

Rush declares that either too much stimulation or too little stimulation causes a state of debility.[14]Corner, Autobiography, 365; Shryock, Medicine and Society in America, 69-72; King, 147-50; Nathan G. Goodman, Benjamin Rush, Physician and Citizen, 1746-1813, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania … Continue reading Too much stimulation brings about indirect debility, too little stimulation direct debility. “Both of these states, if suddenly induced, are accompanied by an increase of excitability, but if chronic both are attended by a reduction of excitability.”[15]Butterfield, 364. Debility is thus the predisposing cause of disease, setting up the circumstances whereby disease can occur. Among the causes of debility are cold; the passions of fear, grief, and despair; famine; excessive evacuations; intemperance of eating and drinking; fatigue; lifting heavy weights; and wounding, bruising or compressing particular body parts.[16]Goodman, 232. Miasma—those putrid exhalations that for Rush brought about the yellow fever epidemic—was another predisposing cause.

The proximate cause of disease is “an excessive, convulsive, or wrong action” or, put another way, the “morbid excitement” of the extreme arteries, that is, of the capillaries.[17]Shryock, Medicine and Society in America, 69. Morbid excitement becomes the only disease state, similar to Brow’s notion of indirect debility; Rush simplified Brown’s two disease states to one. According to William Darlington, a student of Rush’s during the time of the Lewis and Clark expedition, Rush asserted that there were no asthenic diseases, only morbid action, because “if the action be not excessive, or preternatural, in force, it is in frequency.”[18]William Darlington, Notes Taken from the Lectures of Benjamin Rush, M.D. on the Theory & Practice of Physic, vol. 3, 1803-4, 105-107, Manuscript number 10a/105, College of Physicians of … Continue reading

Bleeding and Purging

At the time, fever was viewed as a disease rather than a symptom. Treating “vascular tension” through purging and bloodletting would cure the fever brought about by the “proximate cause” of a particular stimulus. Treatment emphasized depletion of morbid excitement: bleeding—dozens of ounces at a time in bad cases—and purging. Calomel and jalap were preferred purgatives; blended together they became Rush’s pills, taken along by the Corps of Discovery.

One should not see Rush as strictly limiting his treatment to bloodletting and purging. He used other treatments as well and was as concerned as Brown and Cullen were in regard to diet, habits, and activities, especially as these were predisposing causes of disease. It was in the extreme application of bleeding and purging one sees in Rush’s approach that marks a key difference between other theories.

In support of his system, Rush did not offer what we would consider “proof” of its validity: laboratory and clinical evidence of effective treatment (beyond saying he had success with it). Despite in general being a careful observer, Rush’s system is largely “proven” through reasoned analogy and is tied closely to his religious beliefs. For Rush, the physician had to be aggressive in his treatment because of the fallen state of nature. Donald D’Elia writes:

. . . as a consequence of the Fall of man, the operations of nature had become disordered; that it was these erratic operations of nature which had to yield ultimately to the physician’s skill—a skill based upon progressive experience and reason. There must, then, be an opposition between nature and medicine, since nature was man’s imperfect lot after his expulsion from Paradise; and the point of medicine, like Christianity itself, was to overcome nature by means of Christ’s redemptive gift and restore man to his original, perfect state.[19]Donald J. D’Elia, “Dr. Benjamin Rush and the American Medical Revolution,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 110, no. 4, 1966, 229.

The healing power of nature was banished from medicine, even as the “perfect state” in unspoiled America was developing. For Rush (and Jefferson) a healthy public reflected political and social health. Rush—in this case at odds with Jefferson, who thought little of medical theories—saw his system as perfect for a new republican form of government. Medicine would be freed from the tyranny of the over-learned, and Rush’s few, easily graspable principles and treatments could be taught to almost everyone.[20]Ibid., 230. It would be one God and one system of medicine in the new republic.

Notes

| ↑1 | Christopher Clayson, “William Cullen in Eighteenth Century Medicine.” In William Cullen and the Eighteenth Century Medical World, A. Doig, et al., eds., Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 1993, 95. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Lester King, The Medical World of the Eighteenth Century (Chicago University Press, 1958), 139-142. |

| ↑3 | Richard H. Shryock, Medicine and Society in America: 1660-1860 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1972), 68. |

| ↑4 | Günther Risse, “The Brownian System of Medicine: Its Theoretical and Practical Implications,” Clio Medica, vol. 5, 1970, 45. |

| ↑5 | Ibid., 46. |

| ↑6 | Ibid. |

| ↑7 | Ibid., 47. |

| ↑8 | Ibid., 48. |

| ↑9 | King, 143-44. |

| ↑10 | Richard H. Shryock, Medicine and Society in America: 1660-1860 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1972), 70. |

| ↑11 | Lyman H. Butterfield, ed., Letters of Benjamin Rush. 2 vols. (Princeton: University Press, 1951), 646. |

| ↑12 | Ibid., 657-8. |

| ↑13 | J. H. Powell, Bring Out Your Dead: The Great Plague of Yellow Fever in Philadelphia in 1793 (New York: Time, 1965), 80-83. |

| ↑14 | Corner, Autobiography, 365; Shryock, Medicine and Society in America, 69-72; King, 147-50; Nathan G. Goodman, Benjamin Rush, Physician and Citizen, 1746-1813, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1934, 230-35. |

| ↑15 | Butterfield, 364. |

| ↑16 | Goodman, 232. |

| ↑17 | Shryock, Medicine and Society in America, 69. |

| ↑18 | William Darlington, Notes Taken from the Lectures of Benjamin Rush, M.D. on the Theory & Practice of Physic, vol. 3, 1803-4, 105-107, Manuscript number 10a/105, College of Physicians of Philadelphia. |

| ↑19 | Donald J. D’Elia, “Dr. Benjamin Rush and the American Medical Revolution,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 110, no. 4, 1966, 229. |

| ↑20 | Ibid., 230. |