Vast chain of being! which from God began,

Natures ethereal, human, angel, man,

Beast, bird, fish, insect! what no eye can see,

No class can reach! from Infinite to Thee,

From thee to Nothing.

American Deism

Deism[1]From the Latin word deus, meaning god, or deity. A resurgence in Deism began in the late 1990s, which can be tracked on the World Wide Web. as a mode of religious belief emerged during the post-Newtonian 18th-century among the French philosophes, including Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Deists upheld as the first article of every believer’s creed, that there is a God. The common-sense evidence, as expressed by Thomas Paine (1737-1809), the leading American exponent of Deism, was that “God is the power of first cause, nature is the law, and matter is the subject acted upon.” In view of the power that so many kings and despots had arrogated to themselves as self-proclaimed earthly representatives of God,[2]Thomas Jefferson, in his notes for his autobiography, recalled: “Our minds were [in 1769] circumscribed within narrow limits by an habitual belief that it was our duty to be subordinate to the … Continue reading in consideration of the countless atrocities that had been committed worldwide in the name of God, and so as not to be misunderstood themselves, they often referred to the diety in metaphors such as “divine providence” or, as the French phrased it, the “Supreme Being.”

Deists dissociated themselves from the often bitter sectarianism that had been “revealed” to earthbound prophets. They rejected all of the scriptures—the Qur’an of Islam as well as the Old and New Testaments of the Bible—as literal revelations of dogmas which God had allegedly entrusted to his various earthly messengers—”as if the way to god was not open to every man alike.” In other words, Deism was not a church but a rational point of view.

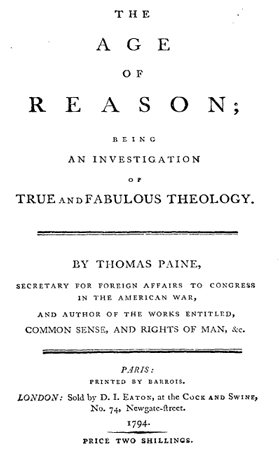

By the end of the 18th century Deism had a firm place in the new United States, alongside many other religions. George Washington was a Deist. So were John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Benjamin Franklin, and Ethan Allen. So were Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. All were either thoroughgoing Deists, or else they subscribed to the basic common-sense values of Deism while maintaining allegiance to the churches in which they were raised. Clark, during his triumphal trip back east from St. Louis in the fall of 1806, was lauded by a citizen of Fincastle, Virginia, on having conducted the enterprise with such incredible success and safety. Clark replied that they should not attribute that outcome to genius on his part or Lewis’s, but to “a singular interposition of providence.”[3]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854, 2nd ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:359. Several years prior to the expedition he had copied into his personal notebook a trenchant statement from Paine’s The Age of Reason (1794-95): “Man cannot make principles, he can only discover them. The most formidable weapon against errors of every kind, is Reason. I believe that religious duties consist in doing justice, loving mercy, and endeavoring to make our fellow-creatures happy.”[4]William Clark Notebook, 1798-1801. Western Historical Manuscripts Collection, Columbia, Missouri. Cited in William E. Foley, Wilderness Journey: The Life of William Clark (Columbia: University of … Continue reading

Clark’s Faith

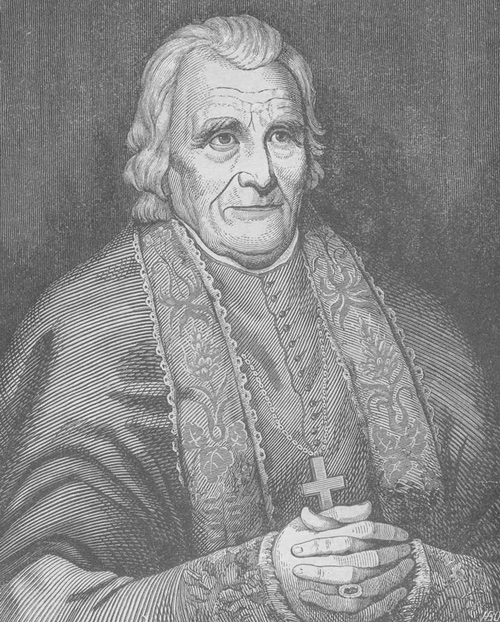

Benedict Joseph Flaget

Unknown artist – Assumption College: Gallery Direct, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=26063728

Benedict Joseph Flaget (7 November 1763–11 February 1850) arrived in America in 1792 and was soon assigned to Fort Vincennes in the Indiana Territory. At the Falls of the Ohio, he was joined by George Rogers Clark on his way down the Ohio River. We do not know if he met George’s younger brother William at that time, but the close connection with the Clark family was established. Father Flaget served as Bishop in Bardstown and Louisville from 1808 to 1850 and was for many years in charge of the Catholic ministry in what was the western frontier at that time.

—Kristopher Townsend, ed.

All his life Clark was consistently “religious but not narrowly sectarian,” according to biographer William Foley.[5]Foley, 256. In 1814, when there was as yet no Anglican clergyman in St. Louis, Clark asked his old friend, Father Benedict Joseph Flaget, bishop of the local, Roman Catholic church, to baptize his three oldest children, and thereafter maintained a pew at Fr. Flaget’s church for the rest of his life. Consistent with his upbringing, in 1819 Clark helped to establish the first Protestant Episcopal parish in St. Louis.

Two days after his death on the first of September 1838, the hearse carrying his remains led a mile-long funeral cortege north along the Mississippi to the burial site on the estate of Clark’s nephew, John O’Fallon. The procession included a company of uniformed militia and a band of musicians. One of Clark’s slaves dressed in mourning clothes led the General’s horse, with sword and military cap hanging form the empty saddle, and empty boots fixed in the stirrups. After Clark’s Masonic brothers conducted their traditional ritual at the graveside, the Right Reverend Peter Minard, Bishop of the Protestant Episcopal Diocese of St. Louis, commenced the Church’s burial rite from the Book of Common Prayer.[6]Ibid, 20, 201, 256, 266.

All Things in Order

It was their faith in the power of inquiry, and of inductive, empirical reasoning that made Lewis and Clark the right leaders to command the expedition. They were compulsive observers of the world around them with all their senses. In January 1804 Clark even copied from the encyclopedia they carried a definition of the word sense, which amounted to a summary of the basics of contemporary scientific method.

It is a faculty of the Soul, whereby it perceive[s] external Objects, by means of the impressions they make on certain organs of the body. These organs are Commonly reconed 5, Viz: the Eyes, whereby we See objects; the ear, which enables us to hear sounds; the nose, by which we received the Ideas of diffferent smells; the Palate, by which we judge of tastes; and the skin, which enables us to feel–the different, forms, hardness, or Softness of bodies.[7]A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . . (London: Printed for W. Owen, 1754).

Moreover, they rigorously exercised what Lewis called their “cogitating faculties.” They were empowered by “the divine gift of reason” to study and learn from nature, which was, as Paine had written, “the Bible of the true believer in God,” which could inspire one with “sublime ideas of the Creator.” If there is anything that explains the explorers’ abilities to maintain their interest in the world around them it was their capacity to concentrate on the scene, and to see beauty and wonder in spite of the many mundane distractions that could have consumed their energies.

One of the fundamental principles of Deism was that God had created all things in a great, hierarchical Chain of Being. The universe was deemed full and complete; nothing could be added or taken away, and God could not be persuaded to change it, nor to interfere in the decisions and conduct of human beings, either as individuals or as nations. The duty and destiny of all humankind was simply to observe and admire the surrounding world, and learn to understand the relationships that held it together. The odyssey of discovery was never finished. During the 18th century, the concept of wilderness had slowly shed its Medieval definition as a metaphor for sin and error. By the time of Lewis and Clark, wilderness was surrendering its ancient reputation as the denizen of the Devil, and slowly emerging as a mirror of the goodness and greatness of the Supreme Being.

Deists on the Trail

The captains, for example, saw their first pronghorns in early September 1804, in northeastern Nebraska, so “wild and fleet” they could not describe even the animal’s color, much less shoot one for a closer look. At mid-month (the 14th), while scanning the horizon for the volcano rumored to be a conspicuous landmark there, they brought down their first antelope, and wrote a concise description of it, referring to the encyclopedia they carried in the company baggage to place it in the context of existing scientific knowledge by comparing it with “the antelope or gazella of Africa,” which neither man had ever seen. Toward the end of that month (on 20 September 1804) one of the hunters brought in two antelope, of which Clark exclaimed, inspired by wonder and admiration, “they are all Keenly made, and is butifull.”

Before Lewis’s six Nez Perce guides turned back on the morning of 4 July 1806, at their campsite on today’s Grant Creek, they hinted “with unfeigned regret” that he and his small detachment were likely to be cut off by “their enimies the Minnetares”—Atsinas, or Gros Ventres, members of the Blackfoot confederacy. That, plus the daily discovery of evidence that war parties had recently passed that way, put the Americans on guard day and night. It could well have utterly distracted them from all else. Yet when Lewis awakened in camp near the mouth of the Sun River on the eleventh, he observed that “the morning was fair and the plains looked beautifull the grass much improved by the late rain. the air was pleasant and a vast assemblage of little birds which croud to the groves on the river sung most enchantingly.”[8]Thomas Paine wrote in a letter to his friend Andrew Dean, on 15 August 1806: “While man keeps to the belief of one God, his reason unites with his creed. . . . His bible is the heavens and the … Continue reading

It was Deism that fundamentally equipped Lewis and Clark to cope with the vicissitudes of travel and exploration in a strange land. Whereas prior generations had despised and feared wildness in Nature as the domain of the Devil and the object lesson of a vengeful God, Deism taught Lewis and Clark to deal with every new situation using plain common sense, and when confronted with circumstances that defied rational explanation and methodical resolution, either to accept them thankfully as the gifts of a benign divinity, or else to consign them to a fateful and irreversible “chapter of accidents.”

Notes

| ↑1 | From the Latin word deus, meaning god, or deity. A resurgence in Deism began in the late 1990s, which can be tracked on the World Wide Web. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Thomas Jefferson, in his notes for his autobiography, recalled: “Our minds were [in 1769] circumscribed within narrow limits by an habitual belief that it was our duty to be subordinate to the mother country in all matters of government, to direct all our labors in subservience to her interests, and even to observe a bigoted intolerance for all religions but hers.” Autobiography Draft Fragment, 6 January through 27 July, 6 January, The Works of Thomas Jefferson in Twelve Volumes. Federal Edition, collected and edited by Paul Leicester Ford (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904). |

| ↑3 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854, 2nd ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:359. |

| ↑4 | William Clark Notebook, 1798-1801. Western Historical Manuscripts Collection, Columbia, Missouri. Cited in William E. Foley, Wilderness Journey: The Life of William Clark (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2004), 20. I am indebted to Prof. Foley for his assistance. |

| ↑5 | Foley, 256. |

| ↑6 | Ibid, 20, 201, 256, 266. |

| ↑7 | A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . . (London: Printed for W. Owen, 1754). |

| ↑8 | Thomas Paine wrote in a letter to his friend Andrew Dean, on 15 August 1806: “While man keeps to the belief of one God, his reason unites with his creed. . . . His bible is the heavens and the earth. He beholds his Creator in all His works, and everything he beholds inspires him with reverence and gratitude.” |