John Godman (1794–1830)

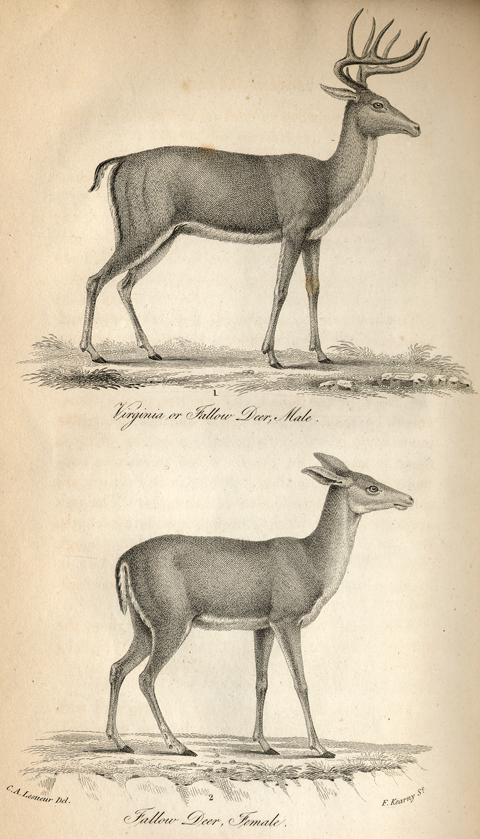

Charles-Alexandre Lesueur‘s illustrations, although almost clinically static, came closer to being lifelike than any that had yet been published.

Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1778-1846)

by Charles Willson Peale (1818)

Oil on canvas, 23½ x 19½ in. Ewell Sale Steward Library, The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.

Lesueur produced 1,500 drawings of zoological specimens on François Péron’s journey to Australia and Tasmania in 1801-1804. He spent 10 years in Philadelphia, where he was an associate of Academy of Natural Science founder William Maclure, and another 12 years in the utopian settlement at New Harmony, Indiana, before returning to Paris.[1]Waldo G. Leland, “The Lesueur Collection of American Sketches in the Museum of Natural History at Havre, Seine-Inférieure,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, vol. X, No. 1 (June … Continue reading

A major part of Meriwether Lewis‘s job was to observe and describe the flora and fauna of the Northwest. He had no reason to write about the common or fallow deer of the East Coast, although in using it for the purpose of comparison, he gave quite a clear picture of it, overall. Its formal description was the province of specialists such as John Godman. John Godman’s description of the common Virginia deer, which relied partly on Lewis and Clark’s journals, was the fullest to be published up to 1828.

Within a lifetime cut short by tuberculosis at age 35, John Godman (1794-1830) gained prominence as a physician and anatomist, as well as a naturalist. In 1821, he moved from Philadelphia to Cincinnati as professor of surgery at the Medical College of Ohio, and the following year became the founding editor of a medical journal, The Western Quarterly Reporter of Medical, Surgical and Natural Science. His American Natural History[2]John D. Godman, American Natural History: Part I, Mastology, 3 vols. (Philadelphia, 1828-1829; reprint, New York: Arno Press, 1974). “Mastology” had recently been suggested by another … Continue reading was among the first major contributions to the literature of natural science in the U.S.

Godman’s essay on the “common deer,” Cervus virginianus, was typical of his engaging style.[3]Ibid., 306-18. Classifying it in the order Pecora, or ruminant animals (having four stomachs), and the genus Cervus, he listed the common names by which it had been known (Fallow Deer, Caricon Femelle, Cerf de la Louisiane, Virginian Deer, and Cerf de Virginie).[4]The first scientific designation of the eastern white-tailed deer has been credited to a naturalist named Zimmerman in 1780, followed by the Dutch physician and naturalist Pieter Boddaert (1730-1795 … Continue reading He then proceeded to reconcile objective Linnaean systematics with subjective descriptions and anecdotal details.

The Common Deer is the smallest American species at present known, and is found throughout the country between Canada in the north and the banks of the Orinoco in south America. In various parts of this extensive range, considerable varieties in size and colouring are presented by this species, though these being accidental and mutable, require no especial description.

Godman was no pedant; today he would be called a “lumper.” He willingly shared his personal admiration for the species:

The common deer is more remarkable for general slenderness and delicacy of form, than for size and vigour. The slightness and length of its limbs, small body, long and slim neck, sustaining a narrow and almost pointed head, give the animal an air of feebleness, the impression of which is only to be counteracted by observing the animated eye, the agile and playful movements, and admirable celerity of its course when its full speed is exerted. Then all that can be imagined of grace and swiftness of motion, joined with strength sufficient to continue a long career, may be realized.

Red Phase

Farther on, paraphrasing Thomas Say (1819-20), he provided some utilitarian insights that any experienced hunter would have recognized.

In the latter part of the summer the fawn loses the white spots, and in winter the hair grows longer and grayish, when the animal is said by the hunters to be in the gray. To this coat one of a reddish colour succeeds about the end of May and the beginning of June; the deer is then said to be in the red. Towards the end of August, the old bucks begin to change to the dark bluish colour; the doe begins this change a week or two later, when they are said to be in the blue. This coat gradually lengthens until it finally returns to the gray. The skin is said to be toughest in the red, thickest in the blue, and thinnest in the gray; the blue skin is most valuable.[5]In 1781 Pennant had remarked that “the skins are a great article of commerce, 25,027 being imported from New-York and Pensylvania [sic] in the sale of 1764.” Thomas Pennant (1726-1798), … Continue reading

Godman’s explanation of the red phase of the common deer may account for Lewis’s remark on 29 July 1805: “we have killed no mule deer since we lay here [at the Three Forks of the Missouri], they are all of the longtailed red deer which appear qu[i]te as large as those of the United States.” A month later, among the Lemhi Shoshones in the upper Salmon River valley on 14 August 1805, he referred to the “common red deer” that “secrete themselves in the brush when pursued,” which he had previously mentioned as a normal tactic of the Virginia deer.

References to Lewis

Remarking that “the whole of the deer is used by the Indians, and, on pressing occasions, without the previous employment of fire,” Godman quoted several contemporary observers’ accounts, including Biddle’s summary (1:375) of Lewis’s story about some Shoshone men wolfing down the raw entrails of a deer Drouillard had killed:

It was indeed impossible to see these wretches ravenously feeding on the filth of animals, and the blood streaming from their mouths, without deploring how nearly the condition of savages approaches that of the brute creation: yet, though suffering with hunger, they did not attempt, as they might have done, to take by force the whole deer, but contented themselves with what had been thrown away by the hunter.

Neither Lewis nor Biddle realized that what those undernourished bodies hungered for were the calories in the fat, and the salt in the blood.

The naturalist emphasized the superior commercial value of brain-tanned deerskin for gloves and “various articles of dress,” concluding: “Deer skins dressed in this way, however, are very liable to be spoiled by moisture, and rot with great rapidity if they continue for some time exposed to rain.” (That could explain why the Corps of Discovery’s deerskin clothing fell into tatters at Fort Clatsop.)

White-tailed Deer, Odocoileus virginianus

The white-tailed deer is the oldest species of deer in the world today, its first appearance dating back to the Pliocene, perhaps 3.5 million years ago. According to some zoologists, there are now 38 subspecies of the white-tail occupying a range that extends from the jungles of northern South America to the fringes of Canada’s boreal forests, and from the Atlantic Coast to the Pacific Northwest.

Today, says Leonard Rue III, it is “probably our best known, most studied, most controversial, best loved, most sought after, and most disliked species in North America. It all depends upon your viewpoint.” In recent years more than 6,250,000 of the estimated 30 million whitetails in the U.S. alone have been legally harvested by hunters. Another 500,000 have been killed in collisions with motor vehicles, with the collateral result of 300,000 humans injured, 200 killed, and property damage exceeding a billion dollars.[6]Leonard Lee Rue III, The Encyclopedia of Deer (Stillwater Minnesota: Voyageur Press, Inc., 2003), 96, 105. Besides, suburbanites in many North American cities have to contend with the infuriating ability of the species to adapt to a wide range of plants. All that expense and nuisance notwithstanding, the white-tail is endowed with such a disarming demeanor and graceful poise that any human who even hints at a need to diminish its presence by any forceful means will be confronted by angry neighbors determined to save “Bambi.”

Whitetails “are capable of being made tame,” reported Thomas Pennant in 1781, “and when properly trained, are used by the Indians to decoy the wild Deer (especially in the rutting season) within [arrow-]shot.”[7]Thomas Pennant, History of Quadrupeds (London: B. White, 1781), 29. They are indeed gregarious, but from a 21st-century perspective, among all the species and subspecies of the genus Odocoileus, the only one that has practically succeeded as a domestic animal is the reindeer. In that respect, at least, the image of reindeer pulling a sleigh in the best-known Christmas-season poem, is essentially factual.

The spotted coat of the white-tail fawn[8]A fawn is a deer less than one year old. seen here serves as camouflage by breaking up its profile; it is most effective when the young animal, not yet strong enough to save itself by fleeing from a predator, is lying motionless in deep grass.

Tails erect and all white hairs flared for added effect, a white-tailed buck and doe, poised to defend their little fawn with their sharp hooves and antlers, scan the neighborhood with their sharp eyes and sensitive ears. The real significance of the raised white flag of a tail is uncertain to humans, but it is widely believed to show a potential predator that the deer is aware of a threatening presence. Whether it also serves to alert other deer to the danger is open to question. In any case, most predators have to depend on ambush or surprise to capture a fleet doe or buck white-tail for dinner.[9]Adrian Forsythe, Mammals of North America: Temperate and Arctic Regions (Buffalo, New York: Firefly Books, 1999), 315.

The term “white-tail” occurred in the expedition’s journals only once, when Clark, on 5 June 1805, reported that he “Saw great numbers of Elk & white tale deer.” He was merely using it as a descriptor, not as a name. It didn’t come into popular usage until sometime in the 1860s.

Audubon Illustrations

Common American Deer

Drawn from Nature by J. W. Audubon

Courtesy Special Collections and Archives. University of Idaho Library. SPEC QL715A9 1849. On Stone by Wm. E. Hitchcock Lithograph Printed & Colored by J. T. Bowen, Philadelphia. Original size, 8 x 4 in.

While Meriwether Lewis was shopping and studying in Philadelphia, in 1803, a young French expatriot named John James Audubon, destined to make an indelible mark on the cultural face of America, was beginning to get acquainted with his adopted homeland, beginning as a businessman. Self-taught as a naturalist and artist, in 1820 he began his monumental Birds of North America, four “elephant folio” volumes containing 435 color plates that captured his subjects with an energetic, elastic grace. In 1843, he set out to create a second, equally monumental opus, Quadrupeds of North America, which was completed five years later. One-third of its 150 hand-colored lithographs were painted by one of his sons, John Woodhouse, with backgrounds by the latter’s younger brother, Victor.

Common Virginian Deer

Drawn from Nature by J. W. Audubon

Courtesy Special Collections and Archives. University of Idaho Library. SPEC QL715A9 1849. On Stone by Wm. E. Hitchcock Lithograph Printed & Colored by J. T. Bowen, Philadelphia. Original size, 8 x 4 in.

In this striking depiction the artist, whose father had passed on his own knowledge of quadrupeds’ anatomy to his son, has here presented his subjects from the inside out, showing their musculature with intense super-realism.

Between 1839 and 1852, already famous for his beautiful paintings in The Birds of America (4 vols., 1827-38), John James Audubon (1785-1851), aided by his sons John Woodhouse and Victor, and the naturalist John Bachman,[10]Bachman, an ordained minister who continued his demanding pastoral duties while writing for the Audubons without pay, also founded the Lutheran Synod of South Carolina, and the state’s Lutheran … Continue reading published the 3-volume Quadrupeds of North America. It included 150 plates lithographed by the talented William Hitchcock and hand-colored by J. T. Bowen under the artists’ supervision.

In the old process of engraving, lines were gouged into a soft copper plate with sharp instruments. The plate was washed with ink and then wiped dry, leaving ink only in the grooves. When a sheet of paper was pressed against the engraved plate, the image was transferred to it. Lithography, however, used a smooth, flat, porous limestone—about 3″-4″ thick, imported from Bavaria—upon which a design was drawn with a greasy crayon or ink made from wax, lampblack, oil, and soap. The stone was drenched with water, which soaked in everywhere that was not covered by the crayoned image. An oily ink, applied with a roller, adhered to the drawing but not to the wet parts of the stone. When a sheet of paper was pressed against the stone, it received the inked image.

The process of lithography had been invented in 1798, but was not widely employed by the printing industry until after 1820, and another fifty years or so elapsed before the full potential of color lithography was reached—about the time when photographic processes evolved that would eventually replace it. In Audubon’s day, color still had to be applied by hand, as in the old days of engraving. Neither engraving nor lithography have been used by the printing industry since the early 20th century, although they have remained highly valuable as artistic media.

Colors of flora and fauna are the most difficult qualities to capture with paint because their shades and hues depend so much upon the transitory effects of season, time of day, quality of light and shadow, and various other factors. As Bachman reminded John James, “color is as variable as the wind.”[11]Letter, 13 January 1840. Quoted in Alice Ford, John James Audubon (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1964), 368. It was for that reason, primarily, that many 18th-century naturalists preferred plain black and white engravings.[12]To circumvent the uncertainties of paint, elaborate vocabularies were developed, by which colors could be specified, such as Werner’s nomenclature of colours, . . . arranged so as to render it … Continue reading J. J. and J. W. Audubon together carried wildlife illustration a giant step forward. The Audubons presented their subjects in more dynamic attitudes than the others, even in states of repose such as that of the fawn shown above. “In his finest paintings of quadrupeds,” wrote Constance Rourke, “every tiny hair seems spun to tension by cold wind, or by fear, or by the lust for prey, and the small squirrels and prairie dogs and gray rats are shown in fleeting subtle movement.”[13]Constance Rourke, Audubon (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1936), 302. Above all, the subtle nuances of color—”The brush of my old friend, Audubon,” Bachman wrote to Victor, “is a truth-teller.”[14]Letter, November 1844, quoted in Francis Hobart Herrick, Audubon the Naturalist: A History of His Life and Time, 2 vols (New York: Appleton and Company, 1917), 262.M.—made those reverent, often vibrant, paintings of quadrupeds immediately and widely popular. The first edition of Quadrupeds numbered 303 copies; nearly 50 reprints were published up to the end of the 20th century.

With the passage of time the original hues of J. W. Audubon’s conceptions may have faded somewhat, and the paper it was printed on may now be a different shade. Moreover, the unpredictable effects of digital media—especially the virtually incalculable differences in calibration among computer monitors—might mean that what we are seeing on this page today is more or less remote from the artist’s intent. On the other hand, just by chance, it might be exactly right.

Notes

| ↑1 | Waldo G. Leland, “The Lesueur Collection of American Sketches in the Museum of Natural History at Havre, Seine-Inférieure,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, vol. X, No. 1 (June 1923), 53-64. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | John D. Godman, American Natural History: Part I, Mastology, 3 vols. (Philadelphia, 1828-1829; reprint, New York: Arno Press, 1974). “Mastology” had recently been suggested by another naturalist as a synonym for mammology, the study of mammals. Godman died of tuberculosis in 1830, at age 35, so no additional volumes were written. |

| ↑3 | Ibid., 306-18. |

| ↑4 | The first scientific designation of the eastern white-tailed deer has been credited to a naturalist named Zimmerman in 1780, followed by the Dutch physician and naturalist Pieter Boddaert (1730-1795 or 96), who in 1784 published an identification key to a collection of colored engravings by the French naturalist Louis Daubenton (1716-1800). Raymond Burroughs, The Natural History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1969; reprint, East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1995), 124, 322-23. Evidently Jefferson, whose Notes on the State of Virginia was first publlished in Paris in 1785, was then unfamiliar with either Zimmerman’s or Boddaert’s work. |

| ↑5 | In 1781 Pennant had remarked that “the skins are a great article of commerce, 25,027 being imported from New-York and Pensylvania [sic] in the sale of 1764.” Thomas Pennant (1726-1798), History of Quadrupeds (London: B. White, 1781), 30. |

| ↑6 | Leonard Lee Rue III, The Encyclopedia of Deer (Stillwater Minnesota: Voyageur Press, Inc., 2003), 96, 105. |

| ↑7 | Thomas Pennant, History of Quadrupeds (London: B. White, 1781), 29. |

| ↑8 | A fawn is a deer less than one year old. |

| ↑9 | Adrian Forsythe, Mammals of North America: Temperate and Arctic Regions (Buffalo, New York: Firefly Books, 1999), 315. |

| ↑10 | Bachman, an ordained minister who continued his demanding pastoral duties while writing for the Audubons without pay, also founded the Lutheran Synod of South Carolina, and the state’s Lutheran theological seminary. |

| ↑11 | Letter, 13 January 1840. Quoted in Alice Ford, John James Audubon (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1964), 368. |

| ↑12 | To circumvent the uncertainties of paint, elaborate vocabularies were developed, by which colors could be specified, such as Werner’s nomenclature of colours, . . . arranged so as to render it highly useful to the arts and sciences, by Abraham Gottlob Werner (1749-1817), published in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1814. Note that in the prospectus for Lewis’s proposed volume on his discoveries in natural history, nothing was written to indicate whether the illustrations would be in color or not. |

| ↑13 | Constance Rourke, Audubon (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1936), 302. |

| ↑14 | Letter, November 1844, quoted in Francis Hobart Herrick, Audubon the Naturalist: A History of His Life and Time, 2 vols (New York: Appleton and Company, 1917), 262.M. |