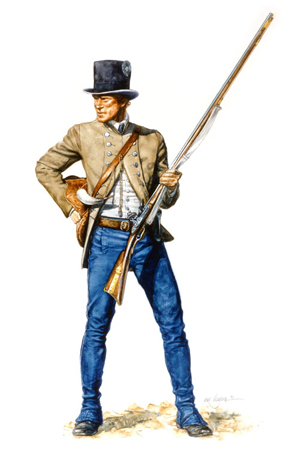

Young Recruit from Kentucky

© Michael Haynes, https://www.mhaynesart.com. Used with permission.

The artist here depicts a Kentucky soldier recruited by Clark—not necessarily William Bratton. This soldier wears a tan coatee and blue overalls as described in Lewis’ 1803 lists made in Philadelphia (See Outfitting the Corps). He carries a model 1792 Springfield (See Muskets and Rifles).[1]Robert J. Moore, Jr. and Michael Haynes, Lewis & Clark: Tailor Made, Trail Worn (Helena: Far Country Press, 2003), 144.

The Starving Days

William Bratton was a taciturn, intelligent man who stood more than six feet tall.[2]Charles G. Clarke, Men of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Glendale: Arthur H. Clark, 1970), 44. As a youth he had been apprenticed to a blacksmith, and so, although there is no mention of it in the journals, it is possible that he, like Alex Willard, might occasionally have assisted the Corps’ principal blacksmith, John Shields. Bratton’s family had moved from Virginia to the Kentucky frontier when the boy was about twelve, and thirteen years later, on 20 October 1803, Clark enlisted him in the Corps of Discovery.

On 11 May 1805, Bratton had one of the men’s most terrifying meetings with a grizzly bear. As the canoes moved up the Missouri River—in present Garfield County, Montana, on a stretch of river now under Fort Peck Lake—Lewis excused him from paddling because of an infected hand, and ordered him to walk on shore and hunt. Late that afternoon Bratton reappeared, running toward the river and yelling to be taken aboard quickly. He had shot a grizzly through the lungs, and the wounded bear had chased him for half a mile. The seven men sent to finish off the bear located and killed it. The bear had lived at least two hours after first being shot.

Mysterious, Painful Illness

In 1806, for four months beginning in February, Bratton “had a tedious illness which he boar with much fortitude and firmness,” as Lewis wrote on 8 June 1806. Bratton was working at Salt Camp when he and George Gibson became very ill, and sent word asking to be replaced. This was done, and the invalids returned to Fort Clatsop on 15 February 1806.

From then through June 8, the captains’ journals mention Bratton’s suffering on 23 different days. His main symptom was extreme pain in the lower back, which kept him from sitting up, and weakness “in the loins” that prevented walking. The captain-doctors tried cinchona bark (See The Botanical Medicines) in potentially dangerous amounts[3]David J. Peck, D.O., Or Perish in the Attempt: Wilderness Medicine in the Lewis & Clark Expedition (Farcountry Press, 2002), 227. and several courses of laxatives, both to no avail. When the Corps headed home up the Columbia River, Bratton still was weak and in great pain. After Clark succeeded in buying horses at The Dalles, “the eighth Bratton was compelled to ride as he was yet unable to walk.” (Clark, 20 April 1806)

Finally, on 24 May 1806 at Camp Chopunnish, Shields recommended that Bratton be given “violent sweats”—a mode of steam-and-cold-water treatment we would call a sauna. He dug a 4-foot-deep hole in the ground, placed stones in the bottom and heated them with fire, then removed the coals and provided a seat where Bratton could be placed, naked, with a vessel of water to sprinkle on the hot stones, producing steam. With the hole covered by a low tent of willow poles and blankets, he endured the steam for 20 minutes, meanwhile drinking “copious draughts of a strong tea of horse mint.” He was then lifted out and twice plunged into the cold river nearby. After undergoing another three-quarters of an hour of steam-induced sweating, he was wrapped in blankets and allowed to cool off gradually. The next day he was able to walk around camp and, at last nearly pain-free, begin [began] slowly to recover his strength. Two weeks later Lewis pronounced him cured.

Dr. David J. Peck, an osteopath and himself a tall man and a sufferer of back pain, believes that Bratton’s illness was likely a “bad case of degenerative disc disease and the arthritis that accompanied it.”[4]Ibid., 249.

Prosperous but Frugal

Bratton became a keelboat freighter on the Mississippi River after the expedition, but re-enlisted in the army for the War of 1812. He married at the age of 41, and fathered eight sons and two daughters. The family lived in Waynetown, Indiana, where Bratton—owner of considerable farmland—was elected justice of the peace. Family stories tell that he was “very saving and could not see anything wasted.” Teased at a corn husking for picking up individual grains, Bratton said “that he had seen the time he would have been very thankful for a few grains of corn,” no doubt recalling his hunger pangs during the westward crossing of the Bitterroots.[5]Post-expedition information is from Morris, Fate of the Corps, 100-101.

Notes

| ↑1 | Robert J. Moore, Jr. and Michael Haynes, Lewis & Clark: Tailor Made, Trail Worn (Helena: Far Country Press, 2003), 144. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Charles G. Clarke, Men of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Glendale: Arthur H. Clark, 1970), 44. |

| ↑3 | David J. Peck, D.O., Or Perish in the Attempt: Wilderness Medicine in the Lewis & Clark Expedition (Farcountry Press, 2002), 227. |

| ↑4 | Ibid., 249. |

| ↑5 | Post-expedition information is from Morris, Fate of the Corps, 100-101. |