A Bad First Impression

Frazer, Hall, and Sgt. Floyd

© Michael Haynes, https://www.mhaynesart.com. Used with permission.

At Fort Southwest Point in Tennessee, a member of Captain Robert Purdy’s company of 2nd Regiment U.S. Army Infantry, and nearing the end of his five-year term of enlistment, Private Hugh Hall volunteered for the Corps of Discovery in 1803. The Fort Southwest Point muster rolls list Hall as born in America and a resident of the town of Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He stood 5ft 8¾ inches with a sandy complexion, fair colored hair, and gray eyes. His occupation was not listed.[1]Moore, Company Book of Captains John Campbell and Robert Purdy, 2nd Regiment, U.S. Infantry, 1803-07, Record Unit 98 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration), vol. 2, no. 104.

Along with seven other volunteers from that post, Hall was guided by George Drouillard to Camp Dubois. On 16 December 1803, the detachment stopped at Cahokia, the temporary headquarters of Meriwether Lewis. The captain was unimpressed with the group, lamenting in a letter to Clark that they were, “not possessed of more of the requisite qualifications; there is not a hunter among them.”[2]Clark eventually selected half the men from Fort Southwest Point to go up the Missouri River: Richard Warfington, John Potts, Thomas Howard, and Hugh Hall.

The group reached Camp at River Dubois on 22 December 1803 and soon William Clark seconded Lewis’s appraisal of the Fort Southwest Point recruits, penning in his journal that, “those men are not such I was told was in readiness at Tennessee for this Comd.” As if to confirm the captains’ evaluations, a scant nine days after his arrival, Hall was among a group of six or seven men who got drunk on New Year’s Eve.

Given Half of a Chance

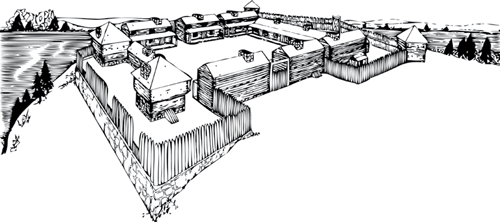

“Fort Southwest Point is the only fort in Tennessee being reconstructed on its original foundation. The completed sections of the fort include a barracks, a blockhouse and 250 feet of palisade walls. The fort is owned, operated, and maintained by the City of Kingston.”[3]Image and text from Fort Southwest Point, http://www.southwestpoint.com/index.html, accessed on 31 August 2017.

Despite Hall’s first impressions, the Captains must have seen qualities that would help the expedition fulfill its mission. They made a note when, in mid-January 1804, Hall supplemented the men’s diet by catching 14 rabbits.

On 1 April 1804, Clark’s orders placed Hall into the first mess under Sgt. Nathaniel Pryor. Soon after heading up the Missouri River, Hall was re-assigned to the second squad led by Sgt. John Ordway, the expedition’s most experienced non-commissioned officer.

An Example for All

Photo © 2015 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The thin rope “tails” symbolized a feline’s proverbial nine lives, derived from its ability to land on its feet after a fall, claws outspread. Once the guilty man was bound in position, hands above his head around a whipping post or tree, the sergeant of the guard “let the cat out of the bag” and began to claw at the man’s back with its blood-stained knots, ten per tail.[4]See Courts Martial on the Trail on this site.

Barely three days out from Camp Dubois, on the night of 16 May 1804, while in the village of St. Charles, Hall was absent without leave along with William Werner and John Collins. Hall and Werner confessed to infraction and were sentenced to 25 lashes on their bare backs. Their punishments were remitted by their commanding officers, and the men were allowed to return to their squads and normal duties.[5]Collins, who faced two additional charges for which he did not admit guilt, was found guilty on all three counts by a panel of enlisted men, and sentenced to 50 lashes. This punishment was carried … Continue reading

On the morning of 29 June 1804, at the mouth of the Kansas River across from present day downtown Kansas City, Missouri, Collins and Hall again faced courts martial, Collins for being “drunk on his post” and for inducing Hall to take whiskey out of the common stores without authorization. Once again Hall pleaded guilty, this time to:

takeing whiskey out of a Keg this morning which whiskey was Stored on the Bank (and under the Charge of the guard) Contrary to all order, rule, or regulation.

To this Charge the prisoner “Pleades Guilty.”

The Court find the prisoner guilty and Sentence him to receive fifty Lashes on his bear Back.

Clark recorded that the sentence was carried out with relish that afternoon as: “the party who we have always found verry ready to punish Such Crimes—”

Hugh Hall’s last involvement in a court martial was very different than the first two experiences. Despite having twice admitted and been judged guilty of offenses, Hall, along with Werner, Collins and others, sat on the opposite side of the bar for the October 13, 1804 court martial trial of John Newman. That jury found Newman guilty.[6]The charges were serious enough to warrant 75 lashes on Newman’s back, reassignment to the red pirogue as a laborer without the right to carry a weapon, denial of the opportunity to stand … Continue reading

Undoubtedly, the courts martial of Hall and the others helped establish discipline and order among all the expedition soldiers.

A Second Chance

After the 1804–1805 winter at Fort Mandan, Hall appeared to be back in the captains’ good graces. He was in the permanent party and just days after leaving Fort Mandan, the captains named a creek on the north side of the Missouri River “Halls Strand Lake.” Not a single other mention of Pvt. Hall occurs in all of 1805 until November 24, when his opinion to cross the Columbia River to determine a site for their winter camp is recorded.

Nearing the end of the expedition’s stay at Fort Clatsop, Hall dropped a log from his shoulder that injured his ankle and foot. One month later, on the return journey eastward, Clark directed Hall to ride a horse that the party had hired from the Nez Perce. Falling out of sight of Capt. Clark, Hall had the horse stolen from him by Umatilla or Yakima Indians.

Nearing the end his tenure with the expedition, while at Long Camp waiting for the snow to melt in the Bitterroot Mountains, Hall and George Gibson brought in meat from a female bear and two cubs that François Labiche had killed the previous day. Four days later, Hall joined Toussaint Charbonneau, John Potts, Peter Weiser and John Thompson in crossing the river by canoe to trade with villagers, hoping to exchange some awls, knitting pins and arm bands for roots to supplement the meat. At 5 p.m., the party returned with six bushels worth of cowse roots and bread made from those roots.

A Non-Swimmer’s Dilemma

On the home-bound journey, Clark’s party was entrusted with the vast majority of the horse herd, and Captain Clark ordered Sgt. Pryor to lead George Shannon and Richard Windsor in driving the horses overland to the Knife River Villages. Unfortunately, the well-trained Indian horses had a tendency to go off uncoaxed to pursue buffalo at varying speeds and in many directions, making it difficult for Nathaniel Pryor’s three-man detachment to keep them under control.

When Pryor’s group met up with Clark’s again on 24 July 1806, the sergeant explained the situation and Hall, who admitted he couldn’t swim, volunteered to assist Pryor in driving the horses. Within a day or two of leaving Clark’s Party, the entire horse herd was stolen. Ironically, Hall would need to float the remaining length of the Yellowstone River in a boat made from willow branches and buffalo hide, a bull boat.

After an extended search Pryor and his men realized they could not overtake the raiders. Undaunted, the men gathered their remaining belongings and hiked to Pompeys Pillar. There Shannon killed some buffalo and the men constructed two bull boats to descend the Yellowstone, unknowingly passing the feature Clark had recently named for Hall. On August 8, they caught up with Clark’s party many miles below the Yellowstone and Missouri River confluence.

Civilian Life

At the conclusion of the expedition, Hall collected $166.66 2/3 in pay. He had problems with his land warrant, and although he apparently did take possession of land in Indiana Territory after March 1807, he later assigned the warrant to another person.

While in the St. Louis area on 11 April 1809, Hall borrowed two dollars from Lewis, becoming in all likelihood one of the last expedition members to see his former captain alive. It is not known if Hugh Hall was married or had children. He was listed in the 1820 census as a farmer living alone in Washington County, Pennsylvania. Hugh Hall is thought to have died between that year and 1830.[7]Larry Morris, The Fate of the Corps (New Haven: Yale University Press), 160, 194.

The Seventh Journalist?

Scholars believe seven enlisted men kept journals on the expedition. The seventh journal writer is unknown but there is some evidence indicating it was Hall. In 1998, John F. Hall, a descendent of Hugh’s apparent brother Charles, revealed in a letter to Barbara Nell that an elderly female relative of his had given him an old journal—supposedly Hugh Hall’s. The journal passed to John F. Hall’s mother, whose house in Bel Air, California was destroyed by fire in early November 1961. The putative journal is thought to have been consumed in the blaze. It may never be determined if Hall or another man was the elusive seventh journal writer.[8]Morris, 160–1.

Notes

| ↑1 | Moore, Company Book of Captains John Campbell and Robert Purdy, 2nd Regiment, U.S. Infantry, 1803-07, Record Unit 98 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration), vol. 2, no. 104. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Clark eventually selected half the men from Fort Southwest Point to go up the Missouri River: Richard Warfington, John Potts, Thomas Howard, and Hugh Hall. |

| ↑3 | Image and text from Fort Southwest Point, http://www.southwestpoint.com/index.html, accessed on 31 August 2017. |

| ↑4 | See Courts Martial on the Trail on this site. |

| ↑5 | Collins, who faced two additional charges for which he did not admit guilt, was found guilty on all three counts by a panel of enlisted men, and sentenced to 50 lashes. This punishment was carried out that evening. |

| ↑6 | The charges were serious enough to warrant 75 lashes on Newman’s back, reassignment to the red pirogue as a laborer without the right to carry a weapon, denial of the opportunity to stand guard, which made him subject to “drudgeries as they may think proper to direct from time to time with a view to the general relief of the detachment,” and expulsion from the permanent party. |

| ↑7 | Larry Morris, The Fate of the Corps (New Haven: Yale University Press), 160, 194. |

| ↑8 | Morris, 160–1. |