Lewis and Clark made celestial observations at “all remarkeable points….” Hassler was tasked with deciphering the celestial data to determine longitude.

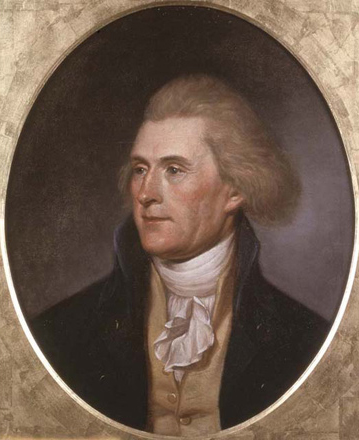

Thomas Jefferson

Charles Willson Peale, Philadelphia, 1791

Courtesy Independence National Historical Park, Philadelphia.

Pursuant to President Jefferson’s orders, Lewis and Clark made celestial observations at “all remarkeable points on the river, & especially at the mouths of rivers.” The purpose of the observations was to obtain data to calculate the latitude and longitude of these points and to correct the expedition’s river survey—based on magnetic north—to true north. By fitting their river survey between points of known latitude and longitude, the Expedition’s estimated distances also could be corrected. The captains made a total of 278 sets of observations at 111 different locations between the mouth of the Missouri and the mouth of the Columbia.[1]The captains reported at least 36 observations attempted between 12 November 1803 and 14 May 1804. From 14 May 1804 until 25 August 1806, I count 278 distinct observations. Equal altitudes (AM and … Continue reading

The calculating of longitude from a celestial observation required the use of complex mathematical procedures based on spherical trigonometry.[2]Navigators themselves rarely use spherical trigonometry any more to find their location, but GPS still uses spherical trig in conjunction with time signals to determine a position. Although almost … Continue reading Those calculations were to have been completed by a qualified mathematician after the expedition’s return. Some of Lewis’s data were given to Ferdinand Hassler, of West Point, for him to work with, but he never finished the job. In December of 1810 Clark sent “a large Connected Map” to his editor, Nicholas Biddle, which was to be included in Biddle’s paraphrase of the captains’ journals. “The Map will not be Corrected by Celestial observations,” Clark wrote, “but I think verry correct.”[3]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition With Related Documents 1783-1854, 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 2:562-63.

Jefferson was not satisfied. In 1816—he was then seventy-three years old—he lamented in a letter to a friend that “the most important justification of [the Lewis and Clark expedition], still due to the public depends on these astronomical observations, as from them alone can be obtained the correct geography of the country, which was the main object of the expedition.”[4]Jefferson to José Corrèa da Serra, 10 July 1816. Ibid., 2:618. da Serra, the Minister from Portugal, who called Washington the “city of magnificent distances,” was a noted … Continue reading Inexplicably, he never succeeded in finding anyone to help him pay his debt to the people.

Completing the Work

Since the mid-1980s other students have made important contributions to understanding the equipment and observational techniques that Lewis and Clark used. Several more have written articles on the results and accuracy of some of the captains’ celestial observations. The following calculations—made especially for Discovering Lewis and Clark®—from the expedition’s celestial observations make use of all the valid data obtained at nine of the expedition’s geographically most significant campsites. These data then were converted into geographic data using procedures that were common at the time of the expedition.[5]I have recalculated all the latitudes and all the chronometer errors on Local Time, but longitudes have been calculated for only about 11 sites, and magnetic declination for about 15.

In the first essay that follows, I review the Astronomy Notebook, an instruction manual that Robert Patterson prepared for Meriwether Lewis‘s reference. In the remaining essays I examine the celestial observations taken at nine of those 111 “remarkeable points,” and solve the problems they pose. Those points are:

- Kansas River Observations

- Fort Mandan Observations

- Marias River Observations

- Missouri Headwaters Observations

- Fortunate Camp Observations

- Clearwater Canoe Camp Observations

- Snake-Columbia Confluence Observations

- The Station Camp Observations

- Long Camp Observations

How much work would it have been for Lewis to complete the entire process of converting his celestial observations into latitudes and longitudes for each one of the locations for which he had taken observations—if he had had the time and the mathematical skill, and if he had completed his observations accurately to begin with? I have provided one example of the entire process as it would have been done during Lewis’s generation,[6]Not included in that mass of calculations is Latitude from the Double Altitude of the Sun, because Lewis didn’t make that observation at the Three Forks of the Missouri. in “Calculations for the Celestial Observations that Meriwether Lewis made at the Three Forks of the Missouri” (PDF). In this instance, the process fills thirty-two consecutive pages with mathematical expressions. It is no wonder that Jefferson excused Lewis from this responsibility.

Obviously, I have not paid Jefferson’s debt in full, nor would there really have been a reason to do so, even back in his day. My choice of sites to complete was based mainly on 1) the quality of the chronometer data, and 2) the site’s location with respect to major changes in the direction of the expedition’s route. A few other sites have fair-to-middling chronometer data and could have been included, but that would have made little difference in a map the scale of the one published in 1814. If Jefferson had wanted a series of more detailed maps, calculations for longitude for other places such as White Catfish Camp and Council Bluff could have been included. But it would have been far more practical to calculate all the latitudes—a comparatively simple exercise—but only the longitudes where the better data existed. Having done that, the compass survey could have been made to fit between as few as these nine control points plus the Missouri’s confluence with the Mississippi. Such a map probably could not have been bettered, at least along the expedition’s route, until the era of the transcontinental railroad surveys.

While Meriwether Lewis was at Camp Island near the Three Forks of the Missouri he spent many hours preparing for and taking celestial observations. From all those observations, however, the only calculations he made were for latitude from the sun’s noon altitude, 28 and 29 July 1805. Lewis’s calculated latitudes, unfortunately, are nearly 30 miles farther south than the true latitude of his Camp Island location. This difference in latitude results from his using the wrong index error for the octant. The other observations were not calculated until nearly two hundred years after Lewis took them; those observations were:

- Two sets of a.m and p.m. Equal Altitudes of the sun to check the chronometer’s time

- Three sets of Lunar Distance observations for longitude (two with the sun, one with Antares)

- Three sets of observations (two with the sun, one with Polaris) to determine the variation of the compass needle or magnetic declination

Before the advent of electronic calculators and computers all the mathematical operations would have been done “long hand.” Multiplication, division, powers and roots would have been done by logarithms. All operations using trigonometric functions also would have been performed using logarithms. In addition, the procedures for making the calculations usually were set out in work-sheet forms in books that had been published by mathematicians trained in making the calculations. Thus, the person doing the calculations merely filled in the observational data in the proper places and followed the outlined procedure, step by step–often without understanding the why or wherefore of the mathematical operations.

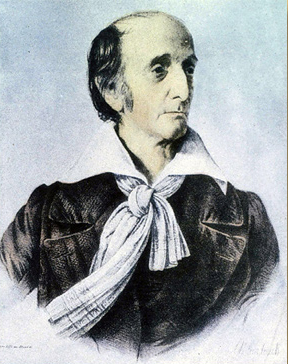

Hassler’s Assignment

Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler (1770-1843) was the person selected to complete the longitude calculations from the observational data that Lewis and Clark brought back. Upon him rested the ultimate materialization of Jefferson’s plan for a map of the Missouri and Columbia Rivers that would be as accurate as modern science could produce. Upon him also rested much of the blame for the plan’s failure.

Hassler was born in Switzerland where, as a youth in Bern, he studied mathematics, astronomy, and surveying. He emigrated to the U.S. in 1805, and soon became associated with Robert Patterson, and John Vaughan of the American Philosophical Society. When Congress established the United States Coast Survey in 1807, Hassler was hired as supervisor, on Patterson’s recommendation. Meanwhile, President Jefferson appointed him as Acting Professor of Mathematics at the new U. S. Military Academy. He was dismissed on 31 December 1809, after the new Secretary of War, John Calhoun, discovered that Congress had not authorized the hiring of civilians to staff the Academy. For the next three years he taught mathematics and Natural Philosophy at Union College in Schenectady, New York.

He was unpopular as a teacher, and was dismissed as the first superintendent of the U.S. Coast Survey after only two years in that very important position. From 1817 until 1830, however, he proved his worth as a theorist, publishing two influential books, Elements of Analytical Trigonometry, and Elements of Arithmetik, Theoretical and Practical. In 1830, President Andrew Jackson appointed him United States gauger, responsible for regulating the national standards of weights and measures. Meanwhile, he was reappointed as superintendent of the United States Coast Survey in 1832, and served successfully in that role also, until his death in 1843.

At Jefferson’s behest Lewis evidently delivered at least some of his and Clark’s records of celestial observations to Hassler early in the spring of 1807, for on 3 May he advanced the mathematician $100 to begin computing the longitudes. On 26 January 1810, three months after Lewis’s death, Clark wrote to Hassler: “The Calculations which you made of the Celistial Observations taken by the late Govr. Lewis (& myself) on the late expedition to the Pacific, are not found among his papers. . . . I flatter my self with a hope that those Calculations with the M[em]orandoms are in your possession.” He requested that Hassler send them to the publisher who was to issue the journals, John Conrad of Philadelphia. Nearly seven months later Hassler sent the following letter to his friend Robert Patterson, still uncertain as to what had been expected of him. (A copy of a map by Clark was immediately forwarded to him; Hassler returned it to Nicholas Biddle, but it has since been lost.) By the following December 20th, despite the free time the mathematician expected to have in late August, Clark had given up. “I am sorry that I could not get the Calculations from Mr. Hosler[sic] to Correct the Map,” he wrote to Biddle, “but, I hope [the final map] will doe without.” Biddle was exasperated with Hassler too, as the next letter suggests.

Hassler’s work with Lewis and Clark’s celestial observations was intermittent and perfunctory, which made it unproductive in the long run. It was unsatisfying to all concerned, for reasons which are implied in the two letters that follow. Hassler’s writing is sometimes difficult to understand, owing to his somewhat limited facility with the English language.

Hassler’s Dilemma

Schenectady [New York] 12th August 1810[7]Autograph letter signed, recipient’s copy; Library of Congress. Jackson, Letters, 2:556-59.

Dear Sir

Some few days ago I received a letter from Mr. Vaughan by which I am very sorry to be informed that he is considerably unwell, I hope it will not be of serious consequences and only transitory, I shall be happy to hear soon of his entire recovery.

This circumstance obliges me to disturb You with these lines, relating to the calculations of Capt. Lewis Voyage of which Mr. Vaughan[8]John Vaughan (1755-1841) was the secretary and librarian of the American Philosophical Society for more than 50 years. It was Vaughan who notified Lewis—via Thomas Jefferson—in late … Continue reading sent me lately the chart, which I compared now with the results before obtained and was now some time ingaged in scrutinising the whole as far as my means reached.I could not go at it before because of the severe sickness of my younger girl who is now recovered from death and in full restablishment, after more than 2 month’s severe sickness.

I had many preparatory Calculations to make to ascertain different points relating to the Elements of the calculation, in calculating backwards from the circumstances & times given what ought to have been observed, so the Err:s Ind:as were otherwise indicated than usually in Math: Obs: the needle was re[a]d once at the north, once at south point &c. &c. After this having made what I could without a chart, which had been promised in the begining, together with the other journals (having only one, in a fair copy, which I see has many faults in writing) I am now in the following difficulties relating to the positions of some interesting points.[9]Poor Hassler! All the mapping he had done in his life, and all the observations he had taken “followed the book.” It’s one thing to start your calculations from a reasonably well … Continue reading

1. The point of Departure, Mouth of River Dubois opposite Missouri Ct. Lewis determines Lat: 38° 55′ 20″ Longit: 89° 57′ 45″ and so I admitted it till I had the chart. But this gives long: about 93° 11′ to this place and sets it opposite Illinois west of the Mississippi. A large map of Hutchins 1778[,][10]Thomas Hutchins (1730-89) was a surveyor and geographer who had published a map titled A new map of the western parts of Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland and North Carolina; comprehending the River … Continue reading an other large map copy of Arrowsmith[11]Aaron Arrowsmith (1750-1823) was the most distinguished cartographer of his era. His maps of North America, especially the editions of 1795 and 1802, were considered the most accurate representations … Continue reading &c. what I could consult[,] gives this place about 2° more west Long: than the confluent of Ohio in MissisIpi, this point is determined by Mr. Ferrere[12]Not identified. 89°06′ which will not agree well together. I therefore tryed to conclude backwards from further points which gives me as follows

From No. 14 two means of results from  Distances give Distances give |

97° 11′ 15" |

| 98 14 15 | |

| The chronometrical determination would give | 95 53 55 |

| Calculating as the observations were intended for and taking the point of departure as he sets it down. | |

| The differences | 1 17 20 |

| 2 20 20 | |

from the results of the  Dist: would give Dist: would give |

91 15 05 |

| by the addition to the Departure, Longitude of this Dep: | 92 18 05 |

which would place this point nearer the determination of other maps and the chart itself. So does also the comparison taken from No. 3 by a similar operation; the Departure is = 91 07 05. These results fall all between Chart numerical Datas given and pretty near the commun maps. But C. L. sais that his Long. is the result of 7 Sets of  Dist: “and may be depended on with safety to 2 or 3 minutes of a degree.” He gives the chronometrical determination 90° 00′ 20″ wherefore the chronometers rate of going was determined at the mouth of the Ohio, with which I just compared it. Which result would you advise me to adopt? The latitude is in the Chart some minutes more south but upon that I think is not to see it (it agrees there about with Hutchins, & Arrowsmith copy).

Dist: “and may be depended on with safety to 2 or 3 minutes of a degree.” He gives the chronometrical determination 90° 00′ 20″ wherefore the chronometers rate of going was determined at the mouth of the Ohio, with which I just compared it. Which result would you advise me to adopt? The latitude is in the Chart some minutes more south but upon that I think is not to see it (it agrees there about with Hutchins, & Arrowsmith copy).

2. My journal in hands goes till Fort Mandan No. 51. The latit: of it Capt. L. gives by mean 47° 21′ 04″ but the Chart 46° 15′ about[,] where lais the error, I must think in the Chart because C. L. has different results which I calculated over and found only such differences as show me that he was not full equal to me in his prop. parts &c. The longitude he determines by the  Eclipse 14th Jany. 1805. The two ends only =

Eclipse 14th Jany. 1805. The two ends only =

6h 37m 31s = 99° 22' 45" |

6 37 47 = 99 26 45 |

But taking the time he indicates for the observation and supposing it corrected (therefore reduced, as he has made the calcul.) I find there a mistake of just 1h which gives reduced for these two results when compared with the nautical Almanac

| 114 22 30 | 13h 41m 30s | |||

| Long | as You will find from | which gives for the times of observation, | ||

| 114 27 30 | 14 39 10 |

without saying if true, mean or watch, time. The Chart places this point nearly 103°. The Lunar Distances give somewhat diverging results above 114°—but I will calculate them once more, having discovered the above error, with the new suppositions for the full accuracy of the prop: parts. What do You advise me to relay [rely] upon here? For the intermediate parts I have no mean[s] of comparison till I have some further Elements; when I come to the south Sea I have some again, by Cooks and Portlof & Dixons Voyages,[13]Captain Nathaniel Portlock (1748?-1817), a veteran of Cook’s third voyage, and himself captain of HMS King George, and George Dixon (d. 1800?), captain of HMS Queen Charlotte, were British … Continue reading for his Chart leads him just about 1° and 2° south of Nutka sound and between two determined points of C. Cook.

I have constructed a Chart Projection upon the principles which I mentioned You on occasion of that of Mr. Garnett,[14]John Garnett was a well-known publisher of tables requisite and nautical almanacs used in astronomical observations, including an American edition of The Nautical Almanac. for the Lat. 38°-48° upon the Elements from the last measurements compared &c. &c. in the scale [1/2,000,000] where I could therefore make all the constructions with accuracy & ease. In less than a fourthnight I shall have pillaged fully the journal I have in hand and to do more I want the subsequent journ: and if a chart is wished containing all the determinations and a sketch which Gen. Clark can then fill with more particulars if wished. I want also the journal of Courses and bearings over the whole, this might give me besides this the, allmost absolutely necessary, advantage of determining those intermediate points of this journal, for which I have not Elements enough; which are numerous, and correct others, or decide on the choice of the observations.

But I should wish to have the originals if possible, be they how they will, they will direct far better than fair copies, which are never faultless. The work is tedious in itself and much more [so] when the very elements must on all possible supposition be tried. I have made more than double the calculations for this purpose than for what will appear in the results.

We have now about 4 weeks more vacancies which would be the the most convenient time for me to give to this work. I should therefore wish to have it as soon as possible, with directions upon the way in which one wished the result, if map & astron: Result, or only the last. If I had had all means, above, I should have done with it about 3. years ago. I shall make as much haste as possible to compleat the whole, when I have the other Elements.

Pray to give our best compliments to Mrs. Patterson and family, and accept my best wishes for Your constant welfare. I remain allways with perfect esteem and sincere attachment Dear Sir Your devoted St.

F. R. Hassler

Biddle’s Opinions

The following paragraphs are from a transcript of a letter that John Vaughan (1756-1841), the librarian and treasurer of the American Philosophical Society, received from Nicholas Biddle, which Vaughan forwarded to Ferdinand Hassler on or about 13 October 1810.[15]Jackson, Letters, 2:560-61. Biddle’s 3rd point may be the unnumbered fourth paragraph, beginning “I presume. . . . “

1st. The river Dubois according to the manuscript of Captn. Clarke which forms the text of the narrative 38° 55′ 17″ the longitude 87° 57∙ 45∙ In my map which is larger and done with more care than that of Mr. Hassler the situation corresponds with those calculations & is I know, almost directly opposite to the mouth of the Missouri. In the same map the 87° degree of longitude crosses the mouth of the Ohio. I incline to think that the slight sketch sent to Mr. Hassler is not to be trusted as to longitude for I understood that its only object was to designate in a general way the places at which the observations were made and of which Mr. Hassler was to fix the longitude by calculation.

2nd. Fort Mandan is mentioned in the manuscript to be in longitude 99. 24. 45–the map has it in 101. There is error somewhere yet it seems difficult to correct it for all that relates to the eclipse in my papers is as follows:

“15 Jany. 1805. This morning between 12 and 3 OClock we had a total eclipse of the moon. A part of the observations necessary for our purpose in this eclipse we got—which is

at 12h total darkness of the moon at 1. 44. end of total darkness at 2. 39. 10 end of the eclipse”

I presume that the time here noted cannot be apparent time or time ascertained by an altitude; nor can it be mean time if by that phrase be meant as I understand time obtained from an altitude corrected by adding or subtracting the equation from the nautical Almanac, since in neither of these cases is it probable that a mistake so great as that of an hour could have occured. But it appears as if the time must be that given by the chronometer at the moment. For in the first place that was the most simple & the probability is that simplest plan was adopted. In the second place from the manner in which the note is made, the silence of the two other persons who kept Journals, and from the circumstance that the young man of the party[16]he young man would have been George Shannon (1785-1836), only 19 when the Corps left Camp Dubois, he was now 25. Clark wrote to Biddle from Louisville on 22 May 1810, to confirm, pursuant to their … Continue reading who is now here knowing nothing of it, it seems probable that the eclipse came on them rather unawares and that having made no preparation, they took the only way in their power of recording the precise time. If therefore they took the time by the chronometer which Mr. Hassler thinks might have been fixed for the Ohio or the mouth of the Missouri, the difference of the hour may perhaps assist the calculation of the longitude–for they had travelled 1600 estimated miles on a course somewhere about northwest.

4th. Judging from what I have heard Captn. Clarke mention I had supposed that he expected from Mr. Hassler the astronomical results only, on obtaining which he proposed making the map himself. But on this subject, as well as that last mentioned Mr. H. might perhaps receive every information by writing to him.

5th. I think it is of importance that Mr. Hassler should possess at least all the courses bearings, & distances during the whole route and I should wish him to see the map I have. But unfortunately the map itself as well as the original journals are so indispensably necessary for my own share of the work that I cannot part with them.

N. Biddle

Hassler’s Challenges

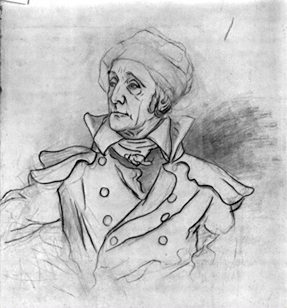

“Pencil sketch of Hassler”

Pencil sketch by Charles Fenderich[17]In addition to two portraits of Hassler, Fenderich is known to have produced only two other lithographs: one from a painting of President William Henry Harrison by a Mr. Franquinet (1841), and his … Continue reading, (Date unknown)

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Fenderich captured Hassler dressed in his favorite fashion, a high-collared ankle-length greatcoat, and a cap to hide his baldness.

It’s not surprising that Ferdinand Hassler had a negative attitude toward calculating the celestial observations Lewis and Clark made. Most of them actually present little or no problem and are merely very time-consuming to interpret. Others, however, might have been much more challenging. For one example, let’s look at the observations taken on 20 May 1805 at and near the mouth of the Musselshell River. Hassler never got anywhere close to having to decipher those data sets, but here’s what he would have had to contend with:

For the Lunar Distance observation, Lewis gives just the mean of the time and the distance for 12 data sets. Clark gives the actual values for the data sets, but lists only 11, not 12; and the 8th and 9th distance are the same (not likely!).

For the Equal Altitudes observation to check the chronometer neither Lewis nor Clark mentions that the AM observation was taken at Point of Observation 20, a few miles downriver from the Musselshell River, whereas the PM observation was taken at Point of Observation 21 at the mouth of the Musselshell. Fortunately the 1’27” latitude difference and the 1’39” longitude difference make only about a second of difference in the chronometer error, but they should have recorded the fact and provided Hassler with their courses and distances so he could determine approximately how far apart the two points were.

The Meridian Altitude observation presents no problem, provided Hassler had access to information on the octant’s index error in the back observation. Lewis, of course, uses an incorrect index error and derives a latitude about 27 minutes too far south without showing his work.

The observation for magnetic declination of the sun has some real problems. First of all, Lewis has the observation being taken in the AM, yet the bearing of the sun for those observations is SW! Clark gives no AM or PM with his values and has 4 data sets compared to Lewis’s 3. In addition, in Moulton’s edition of the journals (4:173) Clark’s 2nd value is S85W whereas in Thwaites (2:55) it is S83W. Obviously, Hassler too would have had to struggle with reading the manuscript numbers. From Lewis’s entry headed “Point of Observation No. 21” in Patterson’s notebook [See Astronomy Notebook]it appears the bearing should be S83W.

But there’s more. If the observation was taken in the afternoon, why is the bearing of the sun going from S85W to S80W? In other words, why is the sun’s bearing tending eastwardly as the day progresses? Apparently Lewis has the numbers 1st, 2nd and 3rd reversed in sequence, yet the times and altitudes appear to be in the proper order.

And, on top of that, Lewis merely gives the altitude of the sun at the time of observation without saying whether it is the upper limb, lower limb or center. In Patterson’s notebook it is given as lower limb and, using the corrected chronometer times, one can calculate that the altitudes Lewis gives are fairly close to what should have been observed for corrected PM times.

Poor Hassler! And to have to do all these calculations on top of his regular duties and family troubles! Maybe we’ve misjudged him.

Persistent Hope

Following his inauguration as the third president of the United States on 4 March 1801, Thomas Jefferson was at last in a position to play a material role in the Age of Exploration. (That era had been initiated about 1450 when Portugal’s Prince Henry the Navigator established the first institute for the teaching of navigation, astronomy, and cartography—the basic tools of discovery.) On 28 February 1803, Congress’s approval and initial funding set in motion his plan to explore a portion of western North America.

As Jefferson had explained to Spain’s Minister to the U.S. a year earlier, his aim was to “send travelers to explore the course of the Missouri River, and for them to penetrate as far as the Southern Ocean.” His overriding purpose, he emphasized, was “to observe the territories which are found between 40° and 60° [north latitude] from the mouth of the Missouri to the Pacific Ocean, and unite the discoveries that these men would make with those which the celebrated Makensie [Alexander Mackenzie] made in 1793″[18]The Spanish minister was Carlos Martínez de Yrujo; the recipient was Spain’s minister of foreign affairs, Pedro Cevallos. The letter, translated by A. P. Nasatir and John Francis McDermott, … Continue reading It was to be, as Jefferson often expressed more concisely, a “literary” undertaking, meaning that the principal immediate outcome would be a book, a travelers’ memoir that the American people could proudly add to the long shelf of published accounts by the likes of Mackenzie, Cook, Vancouver, and many others.

Swiftly the plan materialized. Six months after the secret legislation was passed, Captain Lewis set sail down the Ohio River from Pittsburgh. Nine months later, on 14 May 1804, the voyage was officially under way. Research for the book took two years, four months, and ten days, being completed on 23 September 1806. On the very next morning the explorers “commenced wrighting, &c.” Jefferson was inspired by great expectations. In preparing his Annual Message he was impelled to say that Lewis and Clark “are enabled to give with accuracy the geography of the line they pursued, fixing it in all it’s parts by observations of latitude & longitude.” For some reason, however, he tempered his first impulse with a more modest appraisal. They had, he told Congress on 2 December 1806, “ascertained with accuracy the geography of that interresting communication across our continent.”[19]Autograph document signed, sender’s copy; Library of Congress. Jackson, Letters, 2:352.

Lewis was to have been responsible for the publication of a two-part, three-volume report. Part two would be “confined exclusively to scientific research, and principally to the natural history of those hitherto unknown regions.”[20]Conrad’s Prospectus, printed copy, Missouri Historical Society Library, St. Louis. Jackson, Letters, 2:395. Unfortunately, his life soon began to unravel, coming to a tragic end in suicide on 11 October 1809, leaving unfulfilled ambitions and promises, plus some debts, but without a single word having been written.

Clark sprang into action. The following March he engaged the brilliant young Nicholas Biddle to compile a condensed version of his and Lewis’s journals. With Patrick Gass‘s comparatively superficial diary then in its seventh published edition, Biddle exerted himself—without pay, but with the counsel of General Clark and George Shannon—to complete his paraphrase, which was published in March of 1814. In large part it was old news. Seven and one-half years had elapsed since the close of the accomplishment it documented. Moreover, not only had Benjamin Smith Barton[21]Barton was the pioneer American botanist to whom Lewis consigned many of his plant specimens and who, after Lewis’s death in 1809, had agreed, but never begun, to write the volume on the … Continue reading failed, because of ill health, to produce the natural history volume he had agreed to write after Lewis died (he himself passed away in 1815), but mathematician Ferdinand Hassler had long since given up trying to puzzle out any of Lewis’s 110 sets of celestial observations.

In July 1816, 73-year-old Thomas Jefferson was still trying to assemble all the original documents from the expedition, and he still held out the hope that someone could be found to successfully decipher Lewis’s astronomical observations. He wrote to Clark, urging him to direct Biddle to send him—Jefferson—the data so he could forward them to the War Department for action. “I hope my anxieties . . . in this matter will be excused,” he wrote, “when my agency in the enterprise is considered, and that the most important justification of it . . . depends on these astronomical observations, as from them alone can be obtained the correct geography of the country, which was the main object of the expedition.”[22]Mr. Correa was José Corrèa del Serra (1750-1823), a Portuguese priest, diplomat, and botanist who lived in the U.S. from 1812 to 1820. He helped his friend Thomas Jefferson to gather … Continue reading

Throughout the ensuing year the situation remained at an impasse because the varied circumstances were not yet synchronized. On 28 June 1817 Jefferson wrote to John Vaughan, secretary of the American Philosophical Society:

You enquire for the Indian vocabularies of Messrs. Lewis and Clarke. All their papers are at present under a kind of embargo. They consist of 1. Lewis’s MS. pocket journals of the journey. 2. His Indian Vocabularies. 3. His astronomical observations, particularly for the longitudes. 4. His map, and drawings. A part of these papers were deposited with Dr. Barton; some with Mr. Biddle, others I know not where. Of the pocket journals Mr. Correa[23]John C. Calhoun was Secretary of War from 1817 to 1825. got 4. out of 11. or 12. from Mrs. Barton & sent them to me. He informed me that Mr. Biddle would not think himself authorised to deliver the portion of the papers he recieved from Genl. Clark without his order, whereon I wrote to Genl. Clarke, & recieved his order for the whole some time ago. But I have held it up until a secretary at War is appointed, that office having some rights to these papers. As soon as that appointment is made, I shall endeavor to collect the whole, to deposite the MS. journals & Vocabularies with the Philosphical society, adding a collection of some vocabularies made by myself, and to get the Secy. at War to employ some person to whom I may deliver the astronomical papers for calculation, and the geographical ones for the correct execution of a map; for in that published with his journal, altho’ the latitudes may be correct, the longitudes cannot be.[24]Autograph letter signed, recipient’s copy; American Philosophical Society. Jackson, Letters, 2:630-31.

Clark complied with Jefferson’s request, but negotiations and communications dragged out until, in April of 1818, John Vaughan received some materials, including 14 volumes of the “Pocket Journal of Messrs. Lewis & Clark,” plus “A volume of astronomical observations & other matter by Captain Lewis.”

Thereupon, after 16 years of anticipation, expectation, and frustration, the matter was dropped, apparently without further written comment from anyone. Clark’s map was never corrected. A new plan, in fact, was already under way. In 1819 Major Stephen H. Long, of the Corps of Engineers, was to lead a large, fully manned and equipped, two-year expedition to the rockies. His orders were issued by the Secretary of War, John C. Calhoun, who recommended to Long that he study Jefferson’s 1803 instructions to Meriwether Lewis, which had been included in the preface to Biddle’s edition of the journals.

A Contemporary Attempt

All the calculations that follow were made using an electronic calculator in a non-program mode, and the operations are set out in step-by-step fashion to help the reader follow the complex operations.

The mathematician of the Lewis-and-Clark era would have used the Nautical Almanac for the year of observation. I also used the Nautical Almanacs for 1803–1806 even though there are several excellent computer programs that can recalculate–with greater accuracy and precision than often exists in the almanacs of the time–the needed celestial information. The mathematician of the Lewis-and-Clark era also would have used standard tables such as Tables Requisite to determine the corrections for refraction and parallax and would have used numerous other tables in them to facilitate the tedious long-hand operations. I did not have access to Tables Requisite for the years of the expedition, but used modern formulae to obtain refraction and parallax and other needed parameters. In addition, because most of the navigation tables were designed for use at sea, they do not provide values for refraction at altitudes greater than about 2000 feet.

The calculations made from Lewis’s celestial observations are given below in the following sequence regardless of the date or time at which each was made made:

- Latitude from noon observation of the sun

- Chronometer error at noon from Equal Altitudes observations

- Chronometer time of an observation from any other observation for which the chronometer’s time and sun’s altitude is given

- Longitude from Lunar Distance observations

- Magnetic declination[25]For a complete explanation of calculating geographic location from Lewis’s observations at the Three Forks, see “Calculations for the Celestial Observations that Meriwether Lewis made at … Continue reading

Sources

Florian Cajori, The Chequered Career of Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler (Boston: Christopher Publishing House,1929).

V. Frederick Rickey, “Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler,” A Station Favorable to the Pursuits of Science: Primary Materials in the History of Mathematics at the U.S. Military Academy.

Notes

| ↑1 | The captains reported at least 36 observations attempted between 12 November 1803 and 14 May 1804. From 14 May 1804 until 25 August 1806, I count 278 distinct observations. Equal altitudes (AM and PM) count as only one observation, The same is true for observations for magnetic declination even if taken 10 or so minutes apart, although if AM and PM they are counted as separate observations. Lunar distances are counted by the object observed with the moon even if several sets of 6 to 12 measurements were taken. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Navigators themselves rarely use spherical trigonometry any more to find their location, but GPS still uses spherical trig in conjunction with time signals to determine a position. Although almost all the calculations navigators made before 1993 (except for Latitude from Meridian Altitude) were based on spherical trig, the methods they used were “cook book” applications like Robert Patterson‘s, where the navigator or mathematician followed the procedures outlined in the examples given for each type of observation. My efforts are based on the same procedures. The biggest problem I had was in interpreting them (that is, deciphering the mathematical logic in them) and restructuring them to be used to provide the geographic data needed. |

| ↑3 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition With Related Documents 1783-1854, 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 2:562-63. |

| ↑4 | Jefferson to José Corrèa da Serra, 10 July 1816. Ibid., 2:618. da Serra, the Minister from Portugal, who called Washington the “city of magnificent distances,” was a noted botanist, as well as a famous wit. Margaret Bayard Smith, The First Forty Years of Washington Society (1906, reprint, New York: F. Ungar, 1965), 135. |

| ↑5 | I have recalculated all the latitudes and all the chronometer errors on Local Time, but longitudes have been calculated for only about 11 sites, and magnetic declination for about 15. |

| ↑6 | Not included in that mass of calculations is Latitude from the Double Altitude of the Sun, because Lewis didn’t make that observation at the Three Forks of the Missouri. |

| ↑7 | Autograph letter signed, recipient’s copy; Library of Congress. Jackson, Letters, 2:556-59. |

| ↑8 | John Vaughan (1755-1841) was the secretary and librarian of the American Philosophical Society for more than 50 years. It was Vaughan who notified Lewis—via Thomas Jefferson—in late November of 1804, that he had been elected to the American Philosophical Society. The notification would not have reached Lewis, of course, until his return from the Expedition. Jackson, Letters 1:166n. |

| ↑9 | Poor Hassler! All the mapping he had done in his life, and all the observations he had taken “followed the book.” It’s one thing to start your calculations from a reasonably well known latitude and longitude, and with a chronometer that remains at a single spot for days, where one can be absolutely certain of its rate of going. But it could not be so on a voyage such as that of Lewis and Clark. Not only that, but Lewis obviously was instructed in the simplest methods to make and calculate the observations, involving procedures that worked just by following them through step-by-step without really knowing why they were done. What Hassler is referring to with “Err:as Ind:as” and “Math:Obs” is that Lewis’s Index Errors (Erratas Indicas) had the wrong sign from that generally accepted in mathematical or celestial observational practices. For example, on 22 July 1804, when Lewis describes his scientific instruments he gives the sextant‘s error as 8’45″—; actually, the sextant’s error was +8’45” because it read high by that amount. Thus to correct an observation made with the sextant one had to subtract 8’45” from the observed angle. It all comes out the same if you know what the situation is, but that wasn’t made clear to Hassler. Another example: On 22 July 1804 Lewis gives the error of the octant in the back observation as 2 11′ 40.3+. The octant error in the back observation actually was twice that (4 23’20.6″), and the error was minus because it read low by that amount. But since Lewis always divided the observed angle by two before anything else, he merely added the 2 11′ 40.3 to the observed half angle and everything worked out okay (except during 1805 when he made his calculations using the wrong index error, and didn’t discover it until he was at Fort Clatsop). |

| ↑10 | Thomas Hutchins (1730-89) was a surveyor and geographer who had published a map titled A new map of the western parts of Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland and North Carolina; comprehending the River Ohio, and all the rivers, which fall into it; part of the River Mississippi, the whole of the Illinois River, Lake Erie, part of the Lakes Huron, Michigan, &c., and all the country bordering on these lakes and rivers (London, 1778). It is considered one of the most important maps of 18th-century America. Hutchins later became the first Geographer of the United States. www.davidrumsey.com/maps6355.html, accessed 8 October 2005. |

| ↑11 | Aaron Arrowsmith (1750-1823) was the most distinguished cartographer of his era. His maps of North America, especially the editions of 1795 and 1802, were considered the most accurate representations of the parts of the continent which had yet been explored. John Logan Allen, Lewis and Clark and the Image of the American Northwest (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1975), 78-83. |

| ↑12 | Not identified. |

| ↑13 | Captain Nathaniel Portlock (1748?-1817), a veteran of Cook’s third voyage, and himself captain of HMS King George, and George Dixon (d. 1800?), captain of HMS Queen Charlotte, were British explorer-traders who visited the northwest coast of North America several times between 1785 and 1788 in search of a Northwest Passage. Portlock’s account was published in 1798 as Voyage Around the World; But More Particularly to the Northwest Coast of America. www.americanjourneys.org/aj-089, accessed 8 October 2005. |

| ↑14 | John Garnett was a well-known publisher of tables requisite and nautical almanacs used in astronomical observations, including an American edition of The Nautical Almanac. |

| ↑15 | Jackson, Letters, 2:560-61. Biddle’s 3rd point may be the unnumbered fourth paragraph, beginning “I presume. . . . “ |

| ↑16 | he young man would have been George Shannon (1785-1836), only 19 when the Corps left Camp Dubois, he was now 25. Clark wrote to Biddle from Louisville on 22 May 1810, to confirm, pursuant to their previous conversation, that the “Young Gentleman” would soon arrive in Philadelphia to answer whatever questions might arise relative to the manuscript journals Biddle was paraphrasing. Clark’s recommendation was unqualified: “This Young Gentleman possesses a sincere and undisguised heart, he is highly spoken of by all his acquaintance and much respected at the Lexington University where he has been [studying law] for the last two years.” Biddle was thoroughly satisfied. “I have derived much assistance from that gentleman who is very intelligent and sensible & whom it was worth your while to send here.” Among other things, Shannon helped him select the subjects for the engravings that were included in the book. Jackson, Letters, 2:549, 568. |

| ↑17 | In addition to two portraits of Hassler, Fenderich is known to have produced only two other lithographs: one from a painting of President William Henry Harrison by a Mr. Franquinet (1841), and his own original lithograph of President James K. Polk, “from life on stone” (ca. 1841). |

| ↑18 | The Spanish minister was Carlos Martínez de Yrujo; the recipient was Spain’s minister of foreign affairs, Pedro Cevallos. The letter, translated by A. P. Nasatir and John Francis McDermott, appeared in Nasatir’s Before Lewis and Clark, 2 vols. (1952; repr. Bison Book Edition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990), 712-14. It is reproduced in Jackson, Letters, 2:631. |

| ↑19 | Autograph document signed, sender’s copy; Library of Congress. Jackson, Letters, 2:352. |

| ↑20 | Conrad’s Prospectus, printed copy, Missouri Historical Society Library, St. Louis. Jackson, Letters, 2:395. |

| ↑21 | Barton was the pioneer American botanist to whom Lewis consigned many of his plant specimens and who, after Lewis’s death in 1809, had agreed, but never begun, to write the volume on the expedition’s discoveries in natural history that Lewis had intended to produce. Barton died in 1815 at age 49. |

| ↑22 | Mr. Correa was José Corrèa del Serra (1750-1823), a Portuguese priest, diplomat, and botanist who lived in the U.S. from 1812 to 1820. He helped his friend Thomas Jefferson to gather Lewis’s papers in order to preserve and publish them. See Jackson, Letters, 2:608-09, 615, 617. |

| ↑23 | John C. Calhoun was Secretary of War from 1817 to 1825. |

| ↑24 | Autograph letter signed, recipient’s copy; American Philosophical Society. Jackson, Letters, 2:630-31. |

| ↑25 | For a complete explanation of calculating geographic location from Lewis’s observations at the Three Forks, see “Calculations for the Celestial Observations that Meriwether Lewis made at the Three Forks of the Missouri” (PDF). |