Long before the Lewis and Clark Expedition, life’s cycle at The Dalles followed a yearly sequence of fishing, hunting, harvesting wild foods, and socializing.

Wishham Indians and Canoe (1910)[1]“Wishram” is the currently accepted spelling of the name. At the Stevens Treaty of 1855, the accepted transliteration of the Indian word was “Wishham,” and Edward Curtis … Continue reading

Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952)

Special Collections, Mansfield Library, The University of Montana, Missoula.

Sepia-toned[2]Until the advent of four-color photography in 1935, most photographs were printed in continuous shades of black and white, called grayscale. Curtis developed his photographs using a paper treated … Continue reading photogravure[3]Photogravure is a photomechanical intaglio printing process in which the image to be printed, such as a photograph, is chemically etched into the surface of the printing plate through a screen … Continue reading print from The North American Indian, Vol. 8, Plate 288. Original size, 46 x 34 cm (18 x 13-1/4).

On the bow of the graceful dugout canoes is what some white observers have presumed to be a decorative carving of a dog’s head. On the contrary, it is a purely functional and indispensable feature of Columbia River and Northwest Coast canoe design–a notch and brace that a fisherman may use to steady his spear or harpoon.

Life’s Cycle

From the Columbia Plateau to the river’s mouth, Sahaptian and Chinookan-speaking Peoples followed a yearly cycle for fishing, hunting, and harvesting wild foods. Upper Chinookan people of the Columbia River, after fishing the autumn salmon run and picking the last wild fruits, moved away from the river’s strong winds. Through the winter, they lived on dried foods–fish, roots, and berries–in their villages of wood-frame lodges partially sunken into the earth for insulation, the floors carpeted with woven mats. Farther east, the Nez Perce moved down from the Rocky Mountains into protected river bottoms. During winter, Chinookans hunted both sea and land mammals, including sea lions, seals and whales killed during migrations. A few elk and deer might be harvested; shellfish were available all year (although never eaten during summer months).

In the spring, Columbia River people moved back to the river to fish and live in their ground-level rush-and-willow summer lodges.[4]In the fall of 1805, the Corps noted empty lodges along the river, which they then assumed to be abandoned permanent homes. Returning in the spring of 1806, they realized that these were only … Continue reading The eulachon, a type of smelt, was the first fish to run upstream, and its oily flesh was a treat enjoyed even before fresh greens began sprouting. Next, the salmon’s spring return occasioned First Salmon ceremonies (See Salmon Spirit and Sustenance), in which tribes honored Salmon’s bounty, each in its own manner, but all including thanksgiving. After fishing the spring runs on the Columbia and its tributaries, people gradually moved away to hunt, gather roots, and harvest nuts–especially acorns and hazel nuts–and ripe fruits. And, in the summer, people from many Sahaptian and Chinookan tribes visited The Dalles to trade and socialize.

Trading at The Dalles

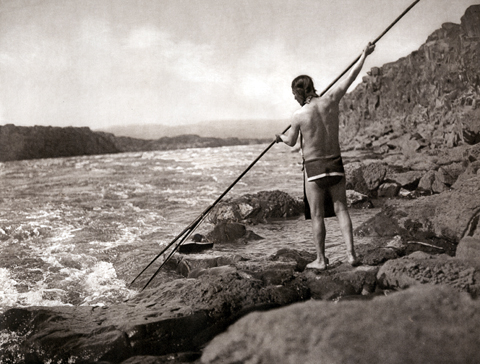

Wishram Indian Spearing Salmon

Special Collections, Mansfield Library, The University of Montana, Missoula

Edward S. Curtis (1909). Sepia-toned photogravure print from The North American Indian, Vol. 8, Plate 276. Original size, 34 x 46 cm. (c. 13-1/4 x 18 in).

Curtis’s caption reads:

The nature of the shore and the height of the water level sometimes combine to make dip-netting impossible. Recourse is then had to the double-pointed spear, the socketed barbs of which are connected to the shaft by strong cords, so that when a fish is struck and its struggles detach the barbs from the prongs it is held by a hook and line.”

Lower Chinookan tribes came up the Columbia to The Dalles, bringing elk hides, compacted cakes of dried salal[5]Salal” is Gaultheria shallon Pursh, also called shallon, an evergreen shrub in the heath family, which thrives on the shady floors of thick pine forests. Clark recorded the Chinookan name, … Continue reading berries, dried clams, and dried wapato roots (Sagittaria latifolia). The Watlalas introduced the Corps of Discovery to roasted wapato, which Lewis described as about the size of a chicken egg. He recognized this plant as the region’s most valuable root crop. Chinookans brought dentalia, or tooth-shaped shells–used in ornamentation–and offered some European trade goods–beads, metal products from knives to kettles to bracelets, and cloth garments–obtained from ships that traded for furs on the Pacific coast. They traded nephrite, a type of hard, light green or white jade that they obtained from Frazier River-area Indians, which was valued for ax heads. Their own tightly woven, waterproof hats and containers were other welcome items, and at The Dalles they in turn traded for new supplies of beargrass (Xerophyllum tenax) to use in weaving, its grass-like leaves gathered by the Upper Chinookan tribes of the Columbia Plateau.

The Nez Perce came to The Dalles offering dried camas roots (Camassia quamash), and some bison products such as jerked meat and hides. The latter came to them through trading with the Shoshones, their connection to the middle Missouri River trading network. Horses had recently become their most important stock in trade, the Nez Perce having acquired the animal around 1730 and become excellent horse breeders.

The trading season usually ended around mid-October, and so the Corps, traveling downstream from late October into November 1805–and returning the next spring just as the first salmon run began–never saw it in full swing. Alexander Ross, clerk of John Jacob Astor’s maritime Astorians who reached the area in 1810, centered the trade on the Long and Short Narrows, which he called “the great emporium or mart of the Columbia.” Ross also noted the gambling games that were part of summer socializing, and the general “roguery” being practiced.

Part of the latter may have been a custom that infuriated the captains: among these tribes, changing one’s mind after making a trade was culturally acceptable. Either buyer or seller could think about a recent deal, or discuss it with family and friends, and change his mind; if a deal was rescinded, the exchanged goods were restored to their original owners. When this happened time and again to Clark, trying desperately to buy horses in the spring of 1806, he perceived it as unethical. Another feature of local trading style was for the seller to set a value and stick to it, refusing to change it; this, too, frustrated Clark in 1806 when his trade-goods stock was small and rapidly dwindling–until then, the Corps had been able to negotiate prices with natives.

As Described by Curtis

Curtis wrote:

In the quiet pools along the rocky shore the salmon sometimes lie resting from their long journey up-stream. The experienced fisherman knows these spots, and by a deft movement of his net he takes toll from each one.

He continued:

These peoples’ position on the river being one of the very best for taking fish, they had an unlimited supply for their own use and ample stores for barter, which gave them everything they needed. From the western ocean were brought shells and sea foods, and through the medium of the Plateau tribes came the buffalo-robes and pemmican of the plains Indians. From the north were brought woven blankets of goat-hair, and the river itself furnished them, as nature’s gift, logs for fuel and for building houses.[6]Edward S. Curtis, The North American Indian, 20 vols. (Norwood, Massachusetts: Plimpton Press, 1911), 8:87.

After the late 1840s, with traders and immigrants arriving in steadily increasing numbers, the old ways were gradually eroded. When photographer Edward Curtis arrived at the turn of the 20th century to document the demise of age-old cultural traditions, he had to bring traditional costumes of the type that few of his subjects were accustomed to wearing any more. Inasmuch as their position as the key traders on the Columbia had always made them comparatively cosmopolitan, a mixture of fashions was still appropriate.

Notes

| ↑1 | “Wishram” is the currently accepted spelling of the name. At the Stevens Treaty of 1855, the accepted transliteration of the Indian word was “Wishham,” and Edward Curtis followed suit fifty years later. Of course, the second h only remotely approximated the conventional aspirate h in English. Differences in orthographic conventions based on varied aural impressions led to various other spellings, such as “Wishum,” “Wisham,” and “Wis-kam.” Curtis spelled the name of the most famous Wishram town as “Nihhluidih,” but it has also been written as “Niculuita.” It is now usually transcribed as “Nixluidix,” although both the h and the x actually stand for unique sounds that are uncharacteristic of English-American speech. Similarly, Lewis and Clark did the best they could to write phonetically accurate vocabularies of key words in the Indian languages they heard at the Great Falls and below, but the “clucking tone anexed which is predomonate” in all of them simply defied their pens. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Until the advent of four-color photography in 1935, most photographs were printed in continuous shades of black and white, called grayscale. Curtis developed his photographs using a paper treated with a sepia-toned emulsion. Sepia was a rich brown pigment made from the inky secretion of the cuttle-fish genus, sepia. In the printing of a negative on paper coated with sepia, a chemical reaction converted metallic silver to a sulphide, which resists fading that otherwise would occur with the passage of time. Optically, moreover, the sepia-toned image appears to have a more readily visible range of shadows and highlights than a grayscale image. Historically, it melded the principle of lithography with the spontaniety of photography. |

| ↑3 | Photogravure is a photomechanical intaglio printing process in which the image to be printed, such as a photograph, is chemically etched into the surface of the printing plate through a screen consisting of tiny square cells (corresponding, electronically, to pixels today). The varying amount of ink held in contiguous squares of different depths produced subtle degrees of density in the printed image. The photogravure process entered the popular press weekly during the first half of the 20th century with the rotogravure, a term which came to denote a section of a newspaper printed on special paper by the photogravure process with a cylindrical, or “rotary,” press, in sepia monochrome. With this step, the lithograph was replaced as a pleasing and economical print medium. (The rotogravure was immortalized by songwriter Irving Berlin in 1915 in “The Easter Parade”—”the photographer will snap us, and you’ll find that you’re in the rotogravure.”) Around 1910, however, photogravures were still printed from flat plates on a letterpress—a slow and expensive process reserved for the finest artistic efforts. Edward Curtis’s monumental collection of photographs was intended to be the ultimate documentation of the then-apparent end of traditional Indian life-ways. Published between 1907 and 1930, The North American Indian consisted of twenty volumes of illustrated narrative plus twenty portfolios containing over 700 large photogravures. The consummation of thirty years’ work, it was enabled by substantial patronage from the wealthy financier J. P. Morgan. |

| ↑4 | In the fall of 1805, the Corps noted empty lodges along the river, which they then assumed to be abandoned permanent homes. Returning in the spring of 1806, they realized that these were only temporary shelters for use during salmon runs, or to escape the other residence when it became infested with Fleas, which would die in a few weeks for lack of blood. By then the Corps had also had seen the more substantial, sunken winter lodges. |

| ↑5 | Salal” is Gaultheria shallon Pursh, also called shallon, an evergreen shrub in the heath family, which thrives on the shady floors of thick pine forests. Clark recorded the Chinookan name, which continues today as the popular name for a plant that supplied food, medicine, and smoking materials through its berries and leaves. The dried berries were cooked with meats and roots in soups. In 1792, Archibald Menzies had gathered specimens on the Strait of Juan de Fuca between Washington and Vancouver Island, Alberta, Canada. Frederick Pursh worked with specimens from both Menzies and Meriwether Lewis. See A. Scott Earle and James L. Reveal, Lewis and Clark’s Green World: The Expedition and Its Plants (Helena, MT: Farcountry Press, 2003), 89-90. |

| ↑6 | Edward S. Curtis, The North American Indian, 20 vols. (Norwood, Massachusetts: Plimpton Press, 1911), 8:87. |