Sacagawea Points to Home

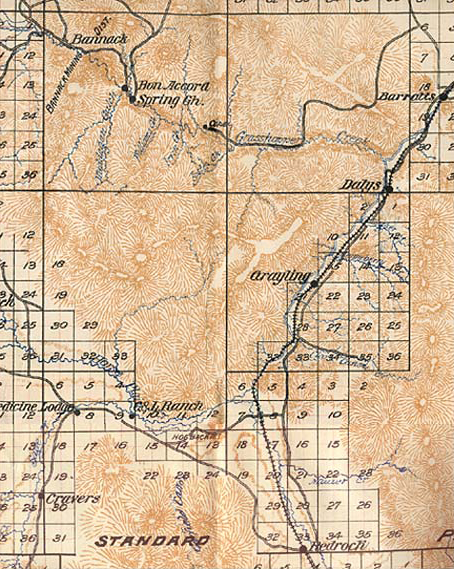

It is true that there were several times when Sacagawea told the captains they were in territory she was familiar with. On 6 July 1806, after following directions a Salish Indian informant had given them the previous September concerning the best road back to the forks of the river they called Jefferson’s, Clark led his party from the headwaters of the Bitterroot River across the divide now called Gibbons Pass. Descending the east slope of the Pass he found himself in “an extensive open Leavel plain in which the Indian trail Scattered in Such a manner that we Could not pursue it.” The Lemhi Shoshone woman promptly informed him that “she had been in this plain frequently and knew it well,” that the creek they were following was a branch of the Big Hole River, and that “when we assended the higher part of the plain we would discover a gap in the mountains[1]Big Hole Pass. in our direction to the canoes.” Moreover, she told Clark, ” when we arrived at that gap we would See a high point of a mountain covered with snow in our direction to the canoes.” That would be Big Hole Pass, at the upper end of the Big Hole Valley, which, Clark later told Nicholas Biddle, was “the great plain where Shoshones gather quawmash [camas] & cows [cous] &c. our woman had done so.”

Sure enough, they “assended a Small rise and beheld an open boutifull Leavel Valley or plain of about 20 Miles wide and near 60 long extending N & S. in every direction” around which Clark could see “high points of Mountains Covered with Snow.” He saw one peak in the distance, “very high covered with Snow which bore S. 80° E.” Sacagawea “pointed to the gap through which she said we must pass which was S. 56° E.”

The next morning Clark dispatched a six-man search team to look for the nine horses—the best mounts they had—that had gone missing. He suspected they might have been stolen by “Some Skulking Shoshones.” Meanwhile, the rest of his contingent pushed on, stopping for lunch at the “Boiling Spring” where the water, he said, “actually blubbers with heat for 20 paces below where it rises.” At day’s end his journal entry was tinged with regret: “I now take my leave of this butifull extensive vally which I call the hot spring Vally.” He was gathering memories—of the hot spring, “a little sulferish”; of pungent “hysoop,” or big sagebrush; of the carrot-like lomatium root. That “remarkable Cold night” they camped near Willard’s Creek.

Back to the Three Forks

On the eighth they proceeded another 11 or 12 miles down Willard’s valley, turned east for nine miles down Horse Prairie Creek, and sometime after noon arrived at Fortunate Camp, the very spot where the young Shoshone-Hidatsa woman had been reunited with her family and friends nearly a year before. Most of the men rushed straight to the cache to satisfy their craving for tobacco. At mid-morning on the tenth “Sergt. Ordway and party arrived with the horses we had lost.” Since departing Travelers’ Rest they had enjoyed an easy six-day trip on a good road that for the most part, “with only a few trees being cut out of the way would be an excellent waggon road.” The fragrant air, mixed with other aromas unintelligible to the white men, must have made Janey nostalgic. The human olfactory sense has a long memory. After breakfast the next morning they loaded up and set out for the Three Forks of the Missouri. They were all going home, including Toussaint Charbonneau and his little family, who would be “discharged and paid up” five weeks later at their village near the Knife River.

Spelling Sacagawea

He wrote it just once—on 24 November 1805, in his tally of the ballots on where they wanted to spend their last winter together. He called her “Janey.” Had Captain Clark been using that congenial, almost affectionate nickname for some time, or did it just spring to mind at that moment? Confinement to their miserable camp on “Point Distress” for two solid weeks must have worn them all down, and drawn them together at a simple human level. The spontaneity of that otherwise pointless opinion poll signified as much. Neighborliness. Protracted crises tend to do that. Polysyllabic jawbreaker names like “Sacagawea” get in the way. For that moment, at least, she was no longer impersonally “the Indian woman,” or “our Interpreter‘s wife,” nor even “the Squaw.” She was just “Janey.” Did he use it before, or afterwards? No one can say.

And for all we know, Janey never saw her old neighborhood again.

Memorial Monument

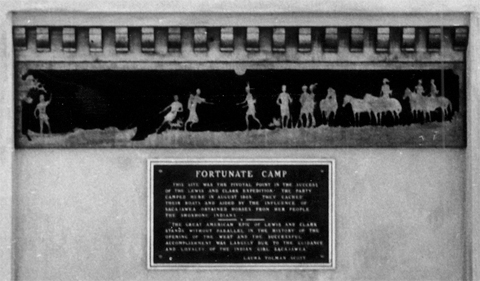

The plaque reads:

This site was the pivotal point in the success of the journey of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The party camped here in August 1805. They cached their boats and aided by influences of Sacajawea obtained horses from her people the Shoshone Indians.

The Great American Epic of Lewis and Clark stands without parallel in the history of the opening of the west and the successful accomplishment was largely due to the guidance and loyalty of the Indian girl Sacajawea.

After the centennial observances in St. Louis and Portland in 1904 and 1905, the next formal commemoration of Sacagawea’s role in the Lewis and Clark expedition was a historical pageant presented in 1915 at the place where it was believed the explorers stepped out of their canoes, the place they dubbed “Fortunate Camp.” The pageant was written by Mrs. Laura Tolman Scott and sponsored by Montana Daughters of the American Revolution.[2]Grace Raymond Hebard, Sacajawea, A guide and interpreter of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with an account of the travels of Toussaint Charbonneau, and of Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, the expedition … Continue reading

The monument shown here was erected in 1937 near the presumed site of Camp Fortunate. It was moved to higher ground in 1962 when construction of Clark Canyon Dam began. The text on the bronze plaque recalls the legend, which had emerged at the turn of the century, that Sacagawea’s principal role was to guide the Lewis and Clark expedition through the West.

Notes

| ↑1 | Big Hole Pass. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Grace Raymond Hebard, Sacajawea, A guide and interpreter of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with an account of the travels of Toussaint Charbonneau, and of Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, the expedition papoose (1932, Mansfield Centre, Connecticut: Overland Trails Press, 1999), 301. |