By displaying the stuffed birds and mammals, the skins and skeletons, and the Indian artifacts to the public, Peale was also preserving the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

The Specimens Arrive

The world was certainly changing in 1806, even as Peale’s American Museum itself was yet going strong. In 1804 Peale had received a first specimen from the Lewis and Clark expedition: a horned lizard. Many more specimens arrived in October 1805, including three live ones (two magpies and a prairie dog). Other specimens arrived later, the items listed in the accession books in 1809 and reported in Poulson’s Daily Advertiser on 1 March 1810.[1]Sellers, Museum, 187. Some items came to Peale’s Museum as late as 1828, the year following his death and when Jefferson’s Poplar Forest Plantation was sold.

As a man who shared Jefferson’s politics, a museum director who benefited from the expedition’s discoveries, and someone with a keen interest in natural history, Charles Willson Peale was as enthusiastic about the expedition as anyone. The future of America had ever-widening possibilities, and Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were two of the new nation’s heroes. The stuffed birds and mammals, the skins and skeletons, and especially the Indian artifacts, that Peale received—mainly from Lewis, through Jefferson—greatly benefited the museum and consequently the public’s appreciation of the expedition. Any number of connections between Peale, the expedition, and its specimens could be enumerated, but it is perhaps most illuminating to concentrate on two: mounting the pronghorn antelope and the relationship between Peale and Lewis.

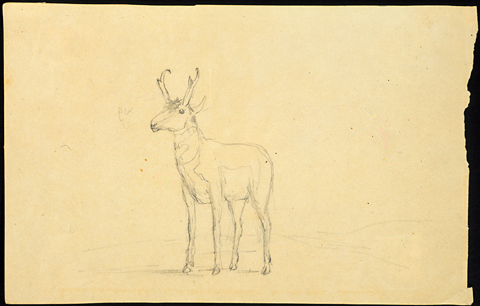

Pronghorn Antelope

Beginning in 1806, one of the most intriguing of all the mounted specimens in Peale’s Museum, not only to visitors but also to Charles himself, was the new species Lewis and Clark had referred to as a “goat,” “cabri,” or “antelope.” Peale proposed the name “Forked Horned Antelope,” but in 1818 the naturalist George Ord (1781-1866) officially bestowed on it the more euphonious “Prong-Horned Antelope.” This pencil sketch was drawn by Titian Ramsay Peale.

Peale expended great effort in preserving the specimens he received in 1805 but especially the pronghorn antelope. Two specimens of the exotic animal Lewis and Clark sometimes called a “goat” arrived via Jefferson in terrible condition. Even in poor condition it was a “fine animal,” the “branched horns perhaps make it a singular animal” that is “a valuable addition to the Museum.”[2]Peale Papers, vol. 2 (Charles Willson Peale: The Artist as Museum Keeper, 1791-1810), pt. 2, CWP to Thomas Jefferson, 3 and 4 November 1805, 908. Peale foresaw the difficulties ahead of him (though he was optimistic about conquering them), and the importance of proceeding. Moreover, he appreciated Lewis’s efforts in enlarging knowledge about nature:

The Skeletons are much broken and I fear some of the bones are lost at the places where they [the packages] have been opened. I can mend the broken bones but cannot make good the deficiency of lost bones, being mixed togather is of no great consequence, as every bone must find its fellow bone. whether I can get an intire Skeleton from all this mass of bones, I cannot yet determine, it will be a work of time and exercise of much patience, this I shall not reguard provided the object is accomplished & the loss of bones will be my only obstacle in the work. I wish the Skeletons had not been mixed with the skins, for the uncleaned bones bred the Insects which afterwards fed on the Skins and has entirely destroyed some of them. If I can mount one of the Antilopes to be decent, it will be a valuable addition to my Antelopes. I am very much obleged to Capt. Lewis for his endeavors to encrease our knowledge of the Animals of that new acquired Territory. . . . It is more important to have this Museum supplied with the American Animals than those of other Countries, yet for a comparative view it ought to possess those of every part of the Globe![3]Ibid., 908-09.

What prodigious feats Peale performed with the skeletons and skins can only be imagined. He was successful, however, and in April 1806 sent Jefferson a detailed description of the specimen.[4]Ibid., CWP to Jefferson, April 5, 1806, 950-52. The drawing is unlocated. In July Peale showed a drawing of the animal and presented a paper to the Philosophical Society, proposing to name it the “forked horned antelope.” Someone replied that that was not a scientific name—true enough, but even Peale’s common name did not remain in use.[5]Ibid., CWP to Jefferson, 4 July 1806,. 974.

The pronghorn illustrates in the most complete way one of a number of contributions Peale made to science by putting the Lewis and Clark specimens in his museum. He worked hard to make an acceptable mount, described the animal, made a drawing of it, and proudly kept it on view. As is noted in the Selected Papers, “the Lewis and Clark Expedition afforded the first scientific investigation of this unique animal,” made possible through the efforts of Charles Willson Peale.[6]Ibid., 954n.

Four Drawings for Lewis

Four Drawings for Lewis’s Book

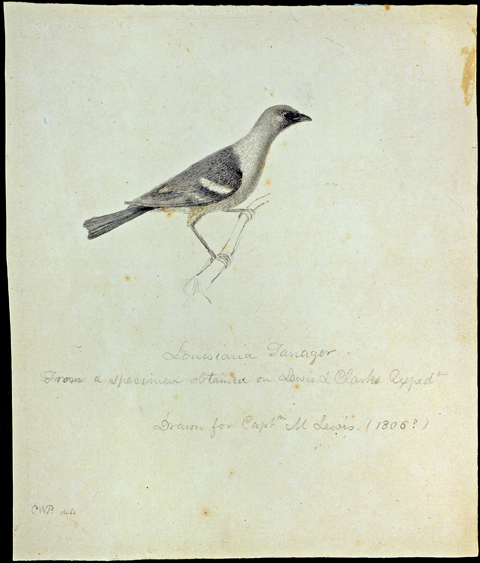

Meriwether Lewis issued two prospectuses in 1804 for a book about his and Clark’s scientific discoveries on the expedition, which was to include engravings of all specimens. He asked Charles Willson Peale to create the drawings, and Peale began with the three live specimens that Jefferson had forwarded to him for the Museum. Unfortunately, Lewis’s book never materialized. The pronghorn above and three drawings below constitute the four drawings discussed here.

“Horned Toad”

“Drawn by CW Peale from a specimen brought by Lewis & Clark”

American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia.

The drawing was made not by “CWPeale” but by Pietro Ancora, an Italian artist and drawing teacher who emigrated to America in 1800.[7]Jackson, Letters, 1:277n. Although it bears certain superficial similarities to both a toad and a frog, Lewis was correct when he named it “Horned Lizzard” (of the genus Phrynosoma) on 29 May 1806.[8]His French engagés told him they called it the “prarie buffaloe,” but Lewis couldn’t understand why they associated this diminutive lizard with the buffalo since, he added … Continue reading The specimen clearly was desiccated by the time it reached Philadelphia.

Somehow, writes Charles Coleman Sellers, “there was a closer relationship . . . between the Philadelphia artist and the moody, self-doubting Lewis than there ever would be between Peale and the loud-laughing, red-headed extrovert Clark.”[9]Sellers, Museum, 186-87. Did Peale recognize and empathize with a melancholic “artistic temperament” in Meriwether Lewis? Whatever the basis of their relationship, in the surviving record Peale has more to say about Lewis than he does about Clark.

In his letters Peale first mentioned Lewis in June 1802 in his capacity as Jefferson’s secretary. Writing to Jefferson, Peale referred to Lewis as “a Young Gentleman (whom I was informed is your secretary)” who cleared up a point about a skull which Jefferson was procuring for Peale.[10]Peale Papers, vol. 2, Charles Willson Peale: The Artist as Museum Keeper, 1791-1810, pt. 1, 6 June 1802, 432-33. Peale and Lewis first met when the latter was in Philadelphia while he was receiving instruction from the Philadelphia friends and mentors; later correspondence of Lewis indicates he must have visited the Museum.[11]Ibid., 582n, and Lewis to Jefferson, 3 October 1803, in Jackson, Letters, 1:126-32.

Lewis returned to Philadelphia in late March 1808 to begin the process of publishing the expedition’s discoveries. He attended three meetings of the Philosophical Society, also attended by Peale: 17 April, 19 June, and 17 July. (Lewis had been elected to membership in 1803.) Stephen Ambrose remarks that Lewis was probably the center of attention, “bombarded with questions from the leading scientific figures of the day” who especially wanted to know his publication plans—a reasonable assumption, but the APS minutes have little detail.[12]Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West (New York, Touchstone, 1997), 433. At the June 19th meeting, the minutes note that “Capt. Lewis requested that he might have the use of certain Specimens of Natural History (the Horned Lizaed excepted) forwarded by him to the President of the Society—for the Society. This request was acceded to.” Peale then “requested that he might be allowed to withdraw his Communication containing a Drawing and description of the forked horned Antelope sent to the Society by Capt. Lewis and assigning as a Reason that he believed Capt. Lewis would present a more perfect description in the Work he was about to publish.”

The Society “acceded to the same.”[13]APS Minutes. Later, Peale wrote John Isaac Hawkins that “I cannot make discriptions of [the birds] in any Public work as Governor Lewis is about publishing his journal, and for which I have made several Drawings of the animals.”[14]Peale Papers, vol. 2, Charles Willson Peale: The Artist as Museum Keeper, 1791-1810, pt. 2, 25 October 1807, 1037. Peale curbed his enthusiasm to help; only three bird drawings were made: mountain quail, Lewis’s woodpecker, and the western (that is, of Louisiana Territory) tanager.[15]Ibid., Charles Willson Peale to Raphaelle Peale, 6 and 7 June 1807, 1018-19. The drawings are in the collections of the APS.

The Captains’ Portraits

As American heroes, Lewis and Clark were worthy to appear in Peale’s portrait gallery. Clark was painted in 1810; Lewis in 1807. These iconic images capture some of the character of each man: Lewis, looking away from the artist, tight-lipped, determined, distant, sad-eyed; Clark, head slightly turned but looking at the artist, open-faced, approachable, no-nonsense, taking it all in, with a suggestion that he is in on the joke.

Cameahwait’s Ermine Tippet

Peale’s great tribute to Lewis—one that regrettably has not survived—was a wax figure. The figure’s face was based on a life mask Peale probably took when doing Lewis’s portrait. Dressed in the ermine tippet given to Lewis by Cameahwait, “its right hand on its breast & the left [holding] the Calumet,“[16]Ibid., Charles Willson Peale to Jefferson, 29 January 1808, 1055-56. the figure represented the optimism and hope of the time, the citizens of the new republic sending the first emissaries of peace and civilization to the many nations of the unexplored West. “My object in this work,” Peale wrote, “is to give a lesson to the Indians who may visit the Museum, and also to shew my sentiments respecting Wars.”[17]Ibid., 1055. In the exhibit was a tablet inscribed with a short speech Peale imagined Lewis might have addressed to Cameahwait:

Brother, I accept your dress—It is the object of my heart to promote amongst you, our Neighbours, Peace and good will—that you may bury the Hatchet deep in the ground never to be taken up again—and that henceforward you may smoke the Calumet of Peace & live in perpetual harmony, not only with each other, but with the white men, your Brothers, who will teach you many useful Arts. Possessed of every comfort in life, what cause ought to involve us in war? Men are not too numerous for the lands which are to [be] cultivate[d]; and Disease makes havock anough amongst them without deliberately destroying each other—If any differences arise about Lands or trade, let each party appoint judicious persons to meet togather & amicably settle the disputed point.[18]Ibid., 1056.

They are more Peale’s words than Lewis’s, but belief in their optimistic Enlightenment message was genuine (if naïve and ethnocentric), more 18th- than 19th-century, when Manifest Destiny was yet a passing thought that had not yet entered the popular imagination or become conscious national policy; when the great explorer, whose image symbolically embraces healing nature in the ermine tippet, offers the peace pipe to Native Americans, all the while at the vanguard of an irresistible flow of people who will bring the “useful arts” that will destroy the Indians’ way of life.

On Lewis’s Suicide

Peale’s final note on Lewis came after the governor’s suicide in October of 1809. Peale wrote his son Rembrandt in Europe that:

Govenor Lewis has distroyed himself—it is said that he had been some time past in bad health & shewed evident signs of derangement, and that having drawn bills for the payment of public services, which were protested because no specific funds had been provided. this mortification compleated his despair, he was on his way to Washington, when at a tavern he shot himself with 2 shots. This not being effectual he cut compleated the rash work with a Razor.[19]Ibid., Charles Willson Peale to Rembrandt Peale, 17 November 1809, 1238.

Peale did not dwell on his personal feelings about Lewis. In the next sentence, the museum director got back to business, noting that “I have received a number of Articles by the way of New Orleans which [Lewis] had sent to the Naval Officer of that Port & by Letter directed him to forward them to me.” Peale thought Lewis would have described the Indian artifacts, skins, and minerals once he returned to Philadelphia, for no letter accompanied the material.[20]Ibid.

Notes

| ↑1 | Sellers, Museum, 187. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Peale Papers, vol. 2 (Charles Willson Peale: The Artist as Museum Keeper, 1791-1810), pt. 2, CWP to Thomas Jefferson, 3 and 4 November 1805, 908. |

| ↑3 | Ibid., 908-09. |

| ↑4 | Ibid., CWP to Jefferson, April 5, 1806, 950-52. The drawing is unlocated. |

| ↑5 | Ibid., CWP to Jefferson, 4 July 1806,. 974. |

| ↑6 | Ibid., 954n. |

| ↑7 | Jackson, Letters, 1:277n. |

| ↑8 | His French engagés told him they called it the “prarie buffaloe,” but Lewis couldn’t understand why they associated this diminutive lizard with the buffalo since, he added whimsically, “there is not greater analogy than between the horse and the frog.” Moulton, Journals, 7:302-03. |

| ↑9 | Sellers, Museum, 186-87. |

| ↑10 | Peale Papers, vol. 2, Charles Willson Peale: The Artist as Museum Keeper, 1791-1810, pt. 1, 6 June 1802, 432-33. |

| ↑11 | Ibid., 582n, and Lewis to Jefferson, 3 October 1803, in Jackson, Letters, 1:126-32. |

| ↑12 | Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West (New York, Touchstone, 1997), 433. |

| ↑13 | APS Minutes. |

| ↑14 | Peale Papers, vol. 2, Charles Willson Peale: The Artist as Museum Keeper, 1791-1810, pt. 2, 25 October 1807, 1037. |

| ↑15 | Ibid., Charles Willson Peale to Raphaelle Peale, 6 and 7 June 1807, 1018-19. The drawings are in the collections of the APS. |

| ↑16 | Ibid., Charles Willson Peale to Jefferson, 29 January 1808, 1055-56. |

| ↑17 | Ibid., 1055. |

| ↑18 | Ibid., 1056. |

| ↑19 | Ibid., Charles Willson Peale to Rembrandt Peale, 17 November 1809, 1238. |

| ↑20 | Ibid. |