Lewis’s “second grand chain”

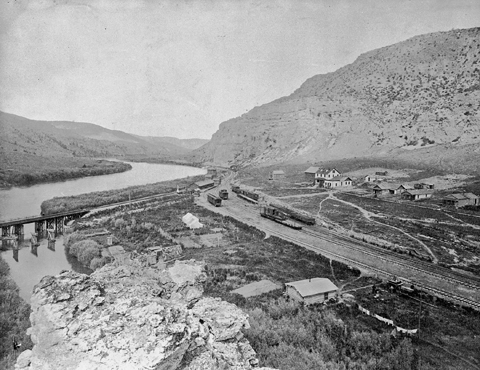

Missouri River Below Toston Dam

© 23 July 2013 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

This is not a panorama photograph. The river actually bends as shown.

Five days and about 55 miles up the fast-flowing river from the entrance to the “gates of the Rocky mountains,” and a day and a half before they reached the headwaters of the Missouri at the Three Forks, Lewis came upon “a bluff point[1]This is the second-to-last of nearly two dozen times the journalists used the term “bluff point” since leaving Fort Mandan on 7 April 1805. It was a common term used by river travelers in … Continue reading where the river again enters the mountains.” Thoughtfully, he added, “I beleive it to be a second grand chain of the rocky Mots.” According to Private Whitehouse, Sacagawea had something to do with that notion. In the afternoon, he explained, they “passed some rough rockey hills, which we expect from the account we have from the Indian Woman that is with us, to be the commencement of the Second chain of the Rockey Mountains; but they do not appear, to be so high, as the first chain of Mountains which we have passed, nor so solid a rock at the entrance of them.”[2]On 22 July 1805, they had passed today’s Beaver Creek, which they called “white Earth Creek . . . from the circumstance of the natives procuring a white paint on this crek.” They … Continue reading There must have been some serious discussion about the importance of that canyon, considering what they could see in the distance, for Whitehouse wrote: “we find that we have not entered the 2nd chain of Mountains but can discover verry high white toped mountains Some distance up the River”—most likely the lofty Tobacco Root Mountains and the Madison Range.

Lewis’s “second grand chain” never became a tourist attraction of the magnitude of the “Great gate of the rock Mounts.” For a few years, however, it was one of the main scenic attractions along the Northern Pacific Railroad mainline that paralleled the Missouri River from the vicinity of the Three Forks to Helena. The tourist’s guidebook informed passengers that there the railroad entered “a savage gorge of weather-worn rocks showing stains of iron and copper, and rising to the height of several hundred feet above the track. On one side of the road runs the swift, clear current of the Missouri, and on the other, tower enormous precipices.” The scenery, the description concluded, was “among the finest on the whole line of the road.”[3]The Great Northwest: a Guide-book and Itinerary for the Use of Tourists and Travelers Over the Lines of the Northern Pacific Railroad (St. Paul: Riley Bros., 1886), 251. Meriwether Lewis’s trip … Continue reading The NP didn’t enter Lewis and Clark’s “Great Gates of the Mountains,” but turned west at Helena to cross the Continental Divide.

Sixteenmile (Howard’s) Creek

Between the “clift” and the creek, six winding river-miles upstream from the “gate” of the supposed “second chain of the Rocky Mountains,” is a spot Lewis typically would have called a “handsome little plain,” though he didn’t this time. Here, in 1882-83 the Northern Pacific Railroad—the first rails to cross the Northwest—built a sidetrack and a water tower to service its steam locomotives on the section that paralleled the Missouri River between the headwaters and Helena, Montana. In 1895 a Helena attorney named Richard Harlow set out to build a railroad up Sixteenmile Creek (so-named because it was 16 miles from the headwaters of the Missouri) to haul ore from the promising silver mines in the Big Belts and the Crazy Mountains. Its western terminus, here where it intersected with the NPRR, was named for A.G. Lombard, its chief construction engineer.

All too soon the mining prospects dimmed, prompting the nickname “Jawbone” line in reference to the persistent persuasion it took to maintain the financing. In 1906 the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railroad—the Milwaukee Road—entered the scene, purchased the 157-mile Montana Railroad as part of its electrified main line, and bridged the Missouri River here, then continued south on the west bank of the river to cross the Divide at Pipestone Pass near Butte.

Lombard thrived for several decades, accessible only by rail. After the U.S. entered the First World War (1917-18) troops were briefly stationed here to guard it against the imagined threat of German saboteurs. In 1930 it was the anonymous setting for a feature film, Danger Lights, billed as “The World’s Greatest Railroad Talk Thriller,” in which “the tough boss of a railroad yard befriends a young hobo and unwittingly places in jeopardy his relationship with the woman he loves.” The cast included future superstars Jean Arthur and Hugh Herbert.

Over the next fifty years, technological improvements and new patterns of travel and commerce rendered the Lombard way-station superfluous. By the 1970s the community was vacant, and the NPRR demolished all remaining structures. Subsequently, the Rocky Mountain Division of the Northern Pacific was purchased by Montana Rail Link, which, as of 2003 was operating twenty freight trains daily past the ghosts of Lombard.[4]William Taylor, “Train Your Lens on That! Three Hot Spots for Railfans,” Montana Magazine, September-October 2003, 8-9. Mr. Taylor has also contributed some details via personal … Continue reading

This part of Lewis and Clark’s “little gates” of the Rockies is still comparatively isolated. A seasonally impassable one-lane road still begins as “improved gravel” at Toston[5]The land on which the town of Toston sprang up about 1882 was given by the U.S. Government to John Karns as “bounty land” for his “meritorious service” in the War of 1812, and … Continue reading but soon deteriorates into a rough, steep and dangerous rock-and-dirt trail. Through traffic by water is also somewhat inconvenient; Tosten Dam, completed in 1940 for irrigation impoundment and flood control, requires a short portage.

“Freestone” Water

At about 11 o’clock on the morning of the 26th the main party passed out of the canyon of this supposed “second chain” of the Rocky Mountains, and proceeded toward the forks. The current was still so rapid, Lewis wrote on the 26th, “that the men are in a continual state of their utmost exertion to get on, and they begin to weaken fast from this continual state of violent exertion.”

The “large spring of freestone” or, as Lewis put it, “very cold and freestone water,” later gained the names “Big,” and the super-sized superlative, “Mammoth.” In 1986 it officially became “Big Spring” (one of ten by that name in Montana alone), by authority of the U.S. Board on Geographic Names.

For several hundred years the term freestone had denoted a fine-grained sandstone or limestone that could be sawn or chiseled easily, and thus served well for construction purposes, including ornaments, monuments and the like. Early in the 19th century it still denoted any layered stone, usually sandstone or, in this region, Madison Group limestone, that easily spalled off in slabs. Groundwater and spring water that flowed through beds of freestone was untainted by ill-tasting minerals such as sulfur, copper, iron or salt, and was preferred for drinking and cooking. As settlers moved westward across the continent, one of the assets in a desirable homestead site was the availability of pure “freestone water.”

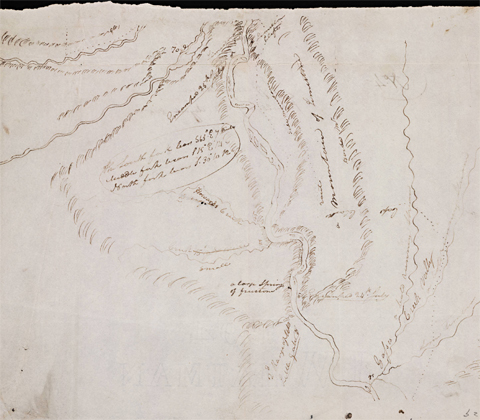

Canyon through the “second chain” of the Rockies

To see labels, point to the map.

Moulton, Atlas map 64. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

As this map indicates, Clark’s overland route caused him to miss this “gate” also. On the 24th he only observed that “the mountains on either Side [of the river] appear like the hills had fallen half down & turned Side upwards.”[6]The low mountains on either side of the Missouri here constitute the western tip of another spur of the Big Belt Mountains. The tilting of the limestone strata is the result of movement along the … Continue reading On the morning of the 25th he arrived at the Three Forks of the Missouri, more than a full day in advance of Meriwether Lewis and his weary crew. For that reason, communication between the two may have broken down temporarily, judging from Clark’s misplacement of Howard’s Creek as well as Lewis’s 25 July campsite.

Highlights

Bluff Point

The face of the country & anamal and vegatable productions,” wrote Lewis, “were the same as yesterday, untill late in the evening, when the valley appeared to termineate and the river was again hemned in on both sides with high caiggy and rocky clifts.’ In his note on the seventh of ten courses for the day, Lewis added: “here the river again enters the mountains I beleive it to be a second grand chain of the rocky Mots.”[7]Moulton, Journals, 4:426, 428. The pipe crossing the river here carries some of the water impounded by Toston Dam to another irrigation ditch on the east side of the river.

Big Spring

Soon after entering these hills or low mountains,” Lewis continued, “we passed a number of [Sgt. Gass said there were six] fine bold springs which burst out underneath the Lard clifts near the edge of the water, they wer very cold and freestone water . . . . two rapids near the large spring we passed this evening were the worst we have seen since that we passed on entering the rocky Mountain; they were obstructed with sharp pointed rocks, ranges of which extended quite across the river.” Private Whitehouse added that they had double-manned the canoes for towing, and that many of the men cut their feet on the sharp rocks.[8]Moulton, Journals, 4:426; 11:240-41. Big Spring has sometimes been termed “artesian,” like the much larger (220 cfs) Giant Springs above Rainbow Dam, 186 miles farther down the Missouri … Continue reading

Toston Dam

Tosten Dam, 6 miles southeast of Toston, Montana, was named for a local pioneer, Thomas Toston. A 705-foot-long concrete gravity dam, it rises 56 feet above the lowest point in the riverbed, producing hydropower, and providing irrigation water for roughly 23,600 acres of farmland downriver. It was completed in 1940 by the State Water Conservation Board, and rehabilitated in 1989 to meet current dam safety standards. The spillway bridge was replaced in 2005, providing public access to the east side of the river.

Lewis’s Campsite, 25 July 1805

Lewis’s flotilla of eight canoes covered 16½ miles on that day. The last course ended at “a Clift of rocks in a Lard. bend; opst. to which we encamped for the night under a high bluff.”[9]Moulton, Journals, 4:428. Many years later the small flood plain beneath that “high bluff” came to be called “Devil’s Bottom.” In 1940 Lewis’s riverside campsite was covered by the reservoir behind Toston Dam.

Howards Creek

The creek Lewis named (on 26 July 1805) for Corps of Discovery enlistee Thomas Howard has been called Sixteenmile Creek since the Northern Pacific Railroad came through here in 1883. The NP tracks are on the east side of the river from Logan, near the Headwaters of the Missouri, to Helena. The track on the west side of the river was the main line of the Milwaukee Railroad (CMSTPP), completed in 1906. The bridge over the river originally crossed the NP’s roadbed on an extension of the river bridge; that span was destroyed by an accident on the NP after the Milwaukee ceased operation in 1986.

Garden Gulch

Four and three-quarter miles from the previous night’s camp, Lewis and his contingent arrived at “the entrance of a small run in a Lard. bend the mouts. here recedes from the river.” This marked the upstream entrance (the south end) of the “Little Gates” of the Rocky Mountains. “This run,” Lewis added, “Capt. C. has laid down in mistake for Howard’s Creek.”[10]Ibid., 4:429-30; Atlas, Map 64.

Notes

| ↑1 | This is the second-to-last of nearly two dozen times the journalists used the term “bluff point” since leaving Fort Mandan on 7 April 1805. It was a common term used by river travelers in those days to denote a high, steep promontory visible from a considerable distance, that marked the end of a course. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | On 22 July 1805, they had passed today’s Beaver Creek, which they called “white Earth Creek . . . from the circumstance of the natives procuring a white paint on this crek.” They recorded a number of “White Earth” rivers and creeks, but this was the only one they so-named in the Rockies. It may be supposed that Sacagawea had helped collect paint there during childhood travels with her tribe, the Lemhi Shoshones, who journeyed to buffalo country annually. That same day Lewis noted that “the Indian woman recognizes the country.” |

| ↑3 | The Great Northwest: a Guide-book and Itinerary for the Use of Tourists and Travelers Over the Lines of the Northern Pacific Railroad (St. Paul: Riley Bros., 1886), 251. Meriwether Lewis’s trip through the canyon was not mentioned. |

| ↑4 | William Taylor, “Train Your Lens on That! Three Hot Spots for Railfans,” Montana Magazine, September-October 2003, 8-9. Mr. Taylor has also contributed some details via personal communication, 7 February 2007. |

| ↑5 | The land on which the town of Toston sprang up about 1882 was given by the U.S. Government to John Karns as “bounty land” for his “meritorious service” in the War of 1812, and later was sold to Thomas Toston, who operated a ferry there. A large smelting operation flourished in Toston for six years beginning in 1883, refining ore from the Big Belt Mountains with coal from the vicinity of Big Spring. |

| ↑6 | The low mountains on either side of the Missouri here constitute the western tip of another spur of the Big Belt Mountains. The tilting of the limestone strata is the result of movement along the Lombard fault, an overthrust that extends for about 14 miles south, toward the headwaters area, and is well exposed in the horseshoe canyon of the Missouri River near Lombard. H.W. Lorenz and R.G. McMurtrey, “Geology and occurrence of groundwater in the Townsend valley, Montana,” Water Supply Paper 1360-C (1956), p. 203. |

| ↑7 | Moulton, Journals, 4:426, 428. |

| ↑8 | Moulton, Journals, 4:426; 11:240-41. Big Spring has sometimes been termed “artesian,” like the much larger (220 cfs) Giant Springs above Rainbow Dam, 186 miles farther down the Missouri River, in which hydrostatic pressure forces the water upward from a source more than 100 feet beneath the surface. However, this smaller (only 56.7 cfs in 1956) Big Spring does not qualify as an artesian spring because it flows from a limestone reservoir that is thirty feet above its discharge point, and its recharge source is even higher, somewhere along upper Sixteenmile Creek. H. W. Lorenz and RG. McMurtrey, “Geology and occurrence of ground water in the Townsend Valley, Montana,” U.S. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 1360-C, 215-16. |

| ↑9 | Moulton, Journals, 4:428. |

| ↑10 | Ibid., 4:429-30; Atlas, Map 64. |