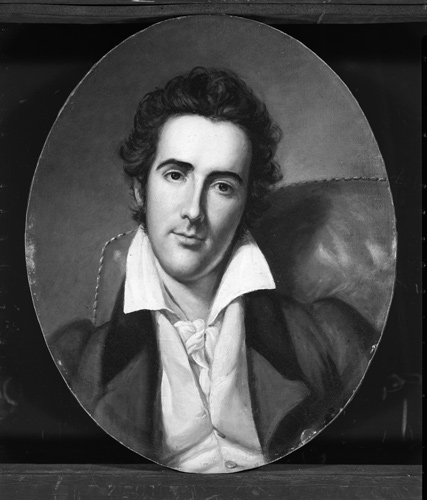

John Davidson Godman (1794-1830)

Figure 1

John Davidson Godman

by Rembrandt Peale (1778–1860)

Oil on canvas, 56.2 x 45.72 cm (22 1/8 x 18 in.). Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts Boston, bequest of Nellie G. Taylor, www.mfa.org/collections/object/dr-john-davidson-godman-32877.

The first naturalist to publish an honest admission of uncertainty over the respective identities of the wild sheep and goat of North America was John Davidson Godman (1794-1830), an anatomist, physiologist, physician, and naturalist whose three-volume American Natural History did much to answer Georges Buffon‘s theory that the United States was bereft of new native species.

Born in Annapolis, Maryland, in 1794, John Davidson Godman was orphaned by age six when first his mother, then his father, and finally his appointed guardian, died. Thereafter he was raised by an older sister in Baltimore. As a youth, soon after he took an apprenticeship with a printer, he began to show symptoms of tuberculosis, the disease that would claim his life in 1830, at the age of thirty-six. He served in the U.S. Navy for a short time in 1814, then began the study of medicine at the University of Maryland, and even lectured on anatomy before graduating in 1818. Failing to receive an appointment to the faculty at his alma mater, he settled in Philadelphia and quickly established a reputation as a specialist in anatomy and physiology, which led to an invitation to join the faculty at the Medical College of Ohio as a professor of surgery. On the very day he left Philadelphia for Cincinnati he married Angelica Kauffman Peale, a daughter of Rembrandt Peale.

In 1821 Godman was appointed to the staff of Charles Willson Peale‘s Museum as a physiologist, along with zoologist Thomas Say and comparative anatomist Richard Harlan. At about that time his youthful fascination with nature seized all his energies and led him quickly to produce what one critic hailed as “the first work by a citizen which has any just claim to the title of an American Natural History.” Godman, the critic continued, “must be admitted as the first who united the ‘System’ of Linnaeus, the charming anecdotal Biographies of Buffon, with the precise anatomical definitions of [Georges] Cuvier.” His illustrations, however, were considered of comparatively little value, the majority having been “copied from every direction, though Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, a French Artist of some cleverness, did many for him.”

During most of his short life Godman professed to be “an established infidel,” which earned him the disdain of many orthodox Christians because, as one of his eulogists pointed out, he had succumbed to the aetheism of the leading eighteenth-century French naturalists, and thus was “guided alone in his investigations by perverted reason.” In the winter of 1827 he experienced an epiphany at the deathbed of a friend, and embraced Christianity. Nevertheless, in his last scientific essays—in which he introduced the concept that would much later become known as “urban wilderness”—he hewed strictly to the objective scientific methods he had practiced all his life.[1]Dictionary of American Biography; John D. Godman, Rambles of A Naturalist; with a Memoir of the Author (Philadelphia: Association of Friends, 1859), 18-19; Charles Wilkins Webber (1819-56), review of … Continue reading

Regrets

Figure 2

Argali

Ovis ammon L.

Argali, Male & Female” Drawing by Alexander Rider (c. 1808-1850). Engraving by R. Kearny from John D. Godman’s American Natural History.

Although Alexander Rider was one of the best known illustrator-artists in Philadelphia at the time, the “figure” he drew to accompany Godman’s “diagnosis” is still, like Edward Savage’s drawing for Samuel Latham Mitchill and Frederick Nodder’s for George Shaw, just another “ram’s head on a deer’s body.” But what else could they do, deprived as they were of a flesh-and-blood model to work from?

In his American Natural History, Godman expresses a desire to learn more about the bighorn sheep:

It is much to be regretted that we are not better acquainted with the peculiar history of this animal drawn up by some one who has studied it in its native wilds . . . . More especially as this species is said to be the source whence all the varieties of our domestic sheep are descended, an opinion which the form and proportions of its body seem to confirm, but one which would scarcely be imagined, if we relied upon the condition of the hair or wool by which the wild animal is covered.

One imagines Godman would have been delighted and edified by Lewis’s original description, if only he could have seen it. Godman continued:

The Argali is found in Northern Asia, and Eastern Siberia, whence it appears gradually to have passed into North America by crossing the ice, where the continents are separated but by a narrow strait.

Two specimens of the argali, a male and female, were brought in by Lewis and Clarke, and may be seen in the Philadelphia [Peale’s] Museum, where they are preserved. The engraving will give a good idea of these animals, though the specimens just mentioned, from which the drawing was made, are much injured by time and exposure to the dust.[2]John D. Godman, American Natural History, 3 vols. (Philadelphia: H. C. Carey & I. Lea, 1826-38), 2:329-31. Godman married Charles Willson Peale’s granddaughter Angelica. Many of the … Continue reading

Godman cited four prior references to argali by contemporary European naturalists. One had named it Ovis fera Sibiricae (Wild Sheep from Siberia). Another called it Ovis montana (sheep of the mountains); a third, Monflor d’ Amerique. Shaw, according to Godman, called it Monflor argali in his fourteen-volume General Zoology (vol. 2, 1800-01); the obsolete generic name, Monflor, is of uncertain source and meaning, but it may once have referred to a Mediterranean subspecies.

Godman’s Description

Figure 3

The Mountain Goat

Capra montana Ord (1816)

Now Oreamnos americanus

Courtesy College of William & Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia

Drawing by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1778-1846). Engraving by G. B. Ellis.

Godman’s 515-word diagnosis contains brief but accurate descriptions of the species’ habitats, the horns of males and females, and their summer and winter pelages. It includes McGillivray’s measurements of the type specimen from which he wrote his notes in the field. Yet several questions remain that seemingly are unanswerable today. First, why didn’t Godman know of George Shaw’s 1804 binomial, and if he did know of it, why did he reject it? Second, on what grounds did he classify the bighorn sheep as an argali? Was he influenced by Thomas Jefferson‘s wild guess? Or was it his own shot in the dark?

This animal concerning which very little is known, is stated by Major Long,[3]Stephen Harriman Long (1784-1864), an officer in the U.S. Army Engineers, was sent west in 1819 in command of an ill-fated military expedition to find the sources of the Platte, Arkansas, and Red … Continue reading in his communication to the Philadelphia Agricultural Society, to inhabit the portion of the Rocky Mountains situated between the forty-eighth and sixty-eighth parallels of north latitude. By Lewis and Clarke it was observed as low as forty-five degrees north.[4]Among the Lemhi Shoshone, during late August 1805. They are in great numbers about the head waters of the north fork of Columbia river, where they furnish a principal part of the food of the natives. They also inhabit the country about the sources of Marias or Muddy River, the Saskatchawan and Athabasca. They are more numerous on the western than on the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains, but are very rarely seen at any distance from the mountains, where they appear to be better suited to live than elsewhere. They frequent the peaks and ridges during summer, and occupy the valleys in winter. They are easily obtained by the hunters but their flesh is not much valued, as it is musty and unpleasant; neither do the traders consider their fleece of much worth. The skin is very thick and spungy and is principally used for the purpose of making moccasins.

The Rocky Mountain goat is nearly the size of a common sheep, and has a shaggy appearance in consequence of the protrusion of the long hair beyond the wool, which is white and soft. Their horns are five inches long and one in diameter, conical, slightly curved backward, and projecting but little beyond the wool of the head. The horns and hoofs are black.

The first indication of this animal was given by Lewis and Clarke, and it is much to be regretted that so little is still known of the manners and habits of this species. The only specimen preserved entire, that we know of, is that figured by Smith in the Linnaean Transactions, from which the figure in our plate is taken. The fineness of the wool of this animal may possibly hereafter induce persons who have it in their power to make some exertions to introduce this species among our domestic animals. It is said that the fleece of this goat is as fine as that of the celebrated shawl goat of Cashmere.[5]Godman, 1:326-28.

Audubon’s Yellowstone Encounter

Figure 5

Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep

through Audubon’s eyes.

Ovis canadensis canadensis Shaw

The Academy of Natural Sciences, Ewell Sale Stewart Library

Drawn from Nature by John James Audubon (1785-1851). Lithographed and colored by J. T. Bowen, Philadelphia, 1845. Original size, 5-1/2 x 8 inches.

We have no truer mission here,” chanted a pious New York critic in 1846, as if echoing Carl Linnaeus‘s epigraph, “than that of Commentators upon, and Illustrators of, God’s first revelation to us–’the Bible of Nature!’ and it would be very difficult to find a Family whose deeds and history more entirely illustrate their recognition of such an Apostleship. They may be called the Levites of a new order of Priesthood in the Temple of Nature!”[6]Charles Wilkins Webber (1819-056), “Audubon’s Quadrupeds of North America,” The American Review, A Whig Journal of Politics, Literature, Art and Science, 4 (December 1846), 629. The patriarchs of the family were the unsaintly John James Audubon, internationally famous for his recent Birds of America (1840-44), and Dr. John Bachman, the Lutheran pastor and scholar who became Audubon’s partner and the author of the texts that accompanied the paintings. The Audubon-Bachman familial connections were intimate. Audubon’s two sons, John W. and Victor G., married Bachman’s two daughters, Mary and Maria,[7]Robert McCracken Peck, “Audubon, Bachman, and the Quadrupeds of North America—John James Audubon and the Reverend John Bachman, Environmentalists,” Magazine Antiques, (November 2000). … Continue reading and their Levitical destiny, as we shall soon see, was occasionally fulfilled by the narratives Bachman supplied to accompany the paintings.

I know no animal which encourages pursuit so much as this. In his flight he frequently turns back, and stares at the hunter with a kind of stupid curiosity, which is often fatal to him.

Audubon and his party encountered a flock of nearly two dozen bighorn sheep near the mouth of the Yellowstone River on 12 June 1843, and had the same experience as the Corps of Discovery’s Private Joe Field had in the same vicinity thirty-eight years earlier: “Notwithstanding all our anxious efforts to get within gun-shot, we were unable to do so.”[8]Alice Ford, ed., Audubon’s Animals: The Quadrupeds of North America (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1951), 300.

“The Rocky Mountain Sheep are gregarious,” Audubon observed,

. . . and the males fight fiercely with each other in the manner of common rams. Their horns are exceedingly heavy and strong, and some that we have seen have a battered appearance, showing that the animal . . . must have butted against rocks or trees, or probably had fallen from some elevation on to the stony surface below. We have heard it said that the Rocky Mountain Sheep descend the steepest hills head foremost, and they may thus come in contact with projecting rocks, or fall from a height on their enormous horns.

Bighorn rams are not sheepish in the colloquial sense of timid or weak. Indeed, they fight more than any other ruminants, says biologist Valerious Geist.

As usual, Audubon’s manneristic style emphasized the subcutaneous musculature of his subjects. He placed them in a realistic setting of the western landscape they inhabited, which was derived from pencil and watercolor sketches by a young assistant, Isaac Sprague. In this case Audubon placed the bighorns at the edge of a cliff high above a verdant mountain park, to suggest their alternate preferences. He enlivened the dead specimens that served as his models with physical beauty and bodily grace, and portrayed them in their typically alert, cautious reaction to the artist’s approach. The ram’s right front hoof is poised, perhaps to paw the ground in a characteristic expression of alarm; the ewe is braced for a leap toward refuge on some narrow rock shelf below.

The bighorns that Audubon and Bachman—and Private Joe Field nearly forty years earlier—saw at the mouth of the Yellowstone were identified as a subspecies of O. c. in 1901 by zoologist C. Hart Merriam (1855-1942), who named it Ovis canadensis auduboni in the artist’s honor. Audubon’s sheep was extirpated from its native range, chiefly by overhunting, sometime between 1910 and 1925. However, mitochondrial DNA studies at the turn of the twenty-first century suggested that Audubon’s bighorn was genetically identical to Ovis canadensis canadensis (Ovis canadensis Shaw).[9]J.J. Beecham, Jr., C.P. Collins, and T.D. Reynolds. (2007, February 12). “Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis): a technical conservation assessment.” [Online]. USDA Forest … Continue reading

Bachman’s Meditation

Standing ‘at gaze,’ on a table-rock projecting high above the valley beyond, and with a lofty ridge of stony and precipitous mountains in the background, we have placed one of our figures of the Rocky Mountain Goat; and lying down, a little removed from the edge of the cliff, we have represented another.

So wrote Audubon’s partner, The Reverend John Bachman (1790-1874), who provided much of the text for Quadrupeds of North America. He continued with a reverent meditation on the species:

In the vast ranges of wild and desolate heights, alternating with deep valleys and tremendous gorges, well named the Rocky mountains, over and through which the adventurous trapper makes his way in pursuit of the rich fur of the Beaver or the hide of the Bison, there are scenes which the soul must be dull indeed not to admire. In these majestic solitudes all is on a scale to awaken the sublimest emotions and fill the heart with a consciousness of the infinite Being “whose temple is all space, whose altar earth, sea, skies.”[10]Bachman has quoted two lines from “The Universal Prayer,” by Alexander Pope (1688-1744). The most popular English poet of the eighteenth century, Pope is still remembered for his Essay on … Continue reading

During the next 50 years the natural sciences were gradually dissociated from such doctrinaire pronouncements.

Osgood’s 1913 Summary

In 1895 a group of taxonomists from many parts of the world established the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature to bring order to what was then an incipient chaos among the taxonomies of animals, by publishing a Code of rules to standardize the procedures.[11]The fourth edition of the Code is available online at http://www.iczn.org/iczn/index.jsp. In 2006 the ICZN launched ZooBank, a world register of 1.5 million scientific names of animals, at … Continue reading However, the Code was slow in sorting out the taxonomic grab-bag relating to the correct name of the bighorn sheep. In 1913 Wilfred H. Osgood (1875-1947), one of the leading mammologists of his generation, lamented that “for nearly twenty years there has been an unfortunate lack of uniform usage respecting the [scientific] name of the Rocky Mountain Sheep. Owing to the size and importance of the animal, it is referred to in many works of sport and travel, and since it has been divided into numerous geographical races, its name is of frequent occurrence in various classes of zoological publications. Therefore agreement as to its scientific name is more than usually desirable.”

Osgood pointed out that, driven by “the habit of disagreement,” zoologists had created a chaos of conflicting taxonomies that could be traced back to a little nomenclatural scrimmage that took place within a three-month period early in 1804, and that it all hinged on uncertainty over the exact date of the issue of The Naturalist’s Miscellany in which George Kearsley Shaw’s disquisition appeared. The impact of that uncertainty was compounded by the fact that the French zoologist Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest (1725-1815) had published the name Ovis cervina (“sheep like a deer”) around the first of March 1804, and a German zoologist named Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber (1739-1810) tendered Ovis montana (“sheep of the mountains”) about April 1. Through exhaustive bibliographical research, however, Osgood found hard evidence that the actual date of Shaw’s publication of Ovis canadensis was 1 February 1804. Whereas Desmarest’s argument consisted of a description without a figure, and von Schreber’s a figure but no description, Shaw’s had all three elements. On the bases of priority and completeness, Ovis canadensis finally claimed its place.[12]Wilfred H. Osgood, “The Name of the Rocky Mountain Sheep,” Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, Vol. 26 (22 March 1913), 57-62. Ibid., “Dates for Ovis Canadensis, … Continue reading The hundred-year wrangle over the rubric was resolved.

Never-ending Story

Now, for the time being at least, we know what to call that noble wild creature with the graceful big horns. Six races of the species Ovis canadensis, totalling approximately 66,000 head, still populate the western United States.[13]Ovis c. canadensis, O. c. californiana, (listed as endangered in the Sierra Nevada in 1999), O. c. nelsoni (the most abundant of the desert bighorn), O. c. mexicana (listed as endangered in New … Continue reading About half of them are Ovis canadensis canadensis, the subspecies to which most of the sheep killed by the Corps of Discovery probably belonged, including the five complete specimens they carried back to the East.

So, is this the end of the story? Not likely, though no one can say what new truths genetic science might uncover, or when. And who knows how the genes of the bighorn sheep and the mountain goat will respond to the climatic changes that are now affecting our own lives. The only reassurance we have is the knowledge that the mammals we call Ovis canadensis Shaw, and Oreamnos americanus (Blainville) have been through similarly profound crises many more times during their Earthly sojourn than we can count.

Notes

| ↑1 | Dictionary of American Biography; John D. Godman, Rambles of A Naturalist; with a Memoir of the Author (Philadelphia: Association of Friends, 1859), 18-19; Charles Wilkins Webber (1819-56), review of “Audubon’s Quadrupeds of North America,” The American Review, A Whig Journal of Politics, Literature, Art and Science, Vol. IV (December 1846), 625-38. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | John D. Godman, American Natural History, 3 vols. (Philadelphia: H. C. Carey & I. Lea, 1826-38), 2:329-31. Godman married Charles Willson Peale’s granddaughter Angelica. Many of the illustrations in Godman’s American Natural History were based on mounted specimens to be seen in Peale’s Museum. Rider’s drawing was based on a sketch made by Titian Ramsay Peale during the Stephen Long expedition in 1819. Carolyn Gilman, Lewis and Clark Across the Divide (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 2003), 174. |

| ↑3 | Stephen Harriman Long (1784-1864), an officer in the U.S. Army Engineers, was sent west in 1819 in command of an ill-fated military expedition to find the sources of the Platte, Arkansas, and Red rivers. It was he who called the Plains from Nebraska to Oklahoma the “Great American Desert.” (Compare Clark’s journal for 26 May 1805.) |

| ↑4 | Among the Lemhi Shoshone, during late August 1805. |

| ↑5 | Godman, 1:326-28. |

| ↑6 | Charles Wilkins Webber (1819-056), “Audubon’s Quadrupeds of North America,” The American Review, A Whig Journal of Politics, Literature, Art and Science, 4 (December 1846), 629. |

| ↑7 | Robert McCracken Peck, “Audubon, Bachman, and the Quadrupeds of North America—John James Audubon and the Reverend John Bachman, Environmentalists,” Magazine Antiques, (November 2000). See also on this site The Audubon Family. |

| ↑8 | Alice Ford, ed., Audubon’s Animals: The Quadrupeds of North America (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1951), 300. |

| ↑9 | J.J. Beecham, Jr., C.P. Collins, and T.D. Reynolds. (2007, February 12). “Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis): a technical conservation assessment.” [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/rockymountainbighornsheep.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2007. |

| ↑10 | Bachman has quoted two lines from “The Universal Prayer,” by Alexander Pope (1688-1744). The most popular English poet of the eighteenth century, Pope is still remembered for his Essay on Criticism (1711), his mock-heroic epic The Rape of the Lock (1714), and his satiric The Dunciad (1728). |

| ↑11 | The fourth edition of the Code is available online at http://www.iczn.org/iczn/index.jsp. In 2006 the ICZN launched ZooBank, a world register of 1.5 million scientific names of animals, at http://www.zoobank.org/query.htm. |

| ↑12 | Wilfred H. Osgood, “The Name of the Rocky Mountain Sheep,” Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, Vol. 26 (22 March 1913), 57-62. Ibid., “Dates for Ovis Canadensis, Ovis Cervina, and Ovis Montana,” Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, Vol. 27 (3 February 1914), 1-4. |

| ↑13 | Ovis c. canadensis, O. c. californiana, (listed as endangered in the Sierra Nevada in 1999), O. c. nelsoni (the most abundant of the desert bighorn), O. c. mexicana (listed as endangered in New Mexico), O. c. cremnobates (chiefly in Baja California, Mexico; the population of this subspecies in southern California was listed as endangered in 1998), and O. c. weemsi (also in Baja California Sur). http://www.bighorninstitute.org/wildsheep.htm. Accessed 16 June 2007.] |