Army Quartermasters

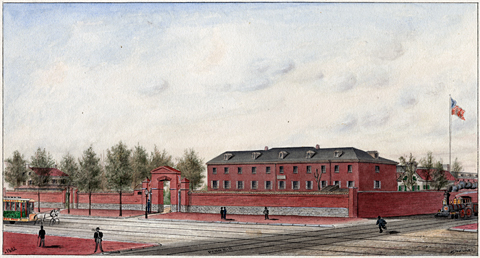

Figure 1

The Schuylkill Arsenal in 1882

Benjamin Ridgway (fl. 1857-1891). watercolor, 25 s 32 cm. (10 x 12-1/2 in.). Library Company of Philadelphia.

The office, warehouse, storage facilities, wood, metal and mechanical shops of the Schuylkill Arsenal were built of brick. The high wall surrounding it was made of brown stone, penetrated on the front by a wide gate to admit wagons, and elsewhere by smaller gates for pedestrians.

From the 15th through the 17th century a quarter master was a subordinate of a ship’s master, with responsibilities for steering the course, attending the binnacle, transmitting signals, and overseeing the stowing of the hold to keep his ship trimmed for efficient headway. By the mid-18th century a quartermaster was an officer “who goeth before hand to prepare quarters for souldiers.” He soon became specifically the officer whose duties were to arrange for quarters for the soldiers, lay out the camp, and see to the acquisition and storage of rations, ammunition, and other supplies. The Quartermaster Department of the American Revolutionary War was a small, underfunded, feeble organization established in 1775 to furnish camp equipment such as tents, lumber and other articles to built huts, and to provide transportation to the Army. Two years later Forage and Wagon departments were added. Meanwhile, a Commissary General and a Clothier General were separately responsible for food and clothing. The winter of 1777 at Valley Forge was a turning point for the Department, bringing reorganization that included the building of the Army’s first support depot (storage) system. The post-Revolutionary Quartermaster Department survived an uneven history until the onset of the War of 1812, when Congress ordered the Department to be reorganized once more, this time under a Quartermaster General assisted by quartermaster captains and quartermaster sergeants. Its function was defined as, “to conduct the procuring and providing of all arms, military stores, clothing and generally all articles of supply requisite for the military service of the United States.”

Assembly at Schuylkill Arsenal

The above quartermaster description pretty well matches the function of the supply depot called Schuylkill Arsenal,[1]Pronounced “school-kill,” often “skoo-kl.” especially in its 1803 role in the Lewis and Clark expedition. Furthermore, from his appointment as leader of the expedition in the winter of 1803 to the day the operation was set in motion from Camp Dubois on 14 May 1804, Meriwether Lewis was acting unofficially in the role of Quartermaster Captain for the volunteer unit that was soon to be unofficially designated as the Corps of Volunteers for North Western Discovery.

The Schuylkill Arsenal, founded in December 1799, was located between the north bank of the Schuylkill River and the road to Grays Ferry,[2]Grays Ferry, by then upgraded to a floating bridge, was one of three crossings of the Schuylkill River on Philadelphia‘s south side, and the one nearest the Delaware River. Meriwether Lewis … Continue reading facing toward the Delaware River a mile away, and the shipyard where the great frigate Philadelphia was under construction. That flagship of the American Navy was to play a sacrificial role in the young nation’s first encounter with the piratical powers of the Middle East, make an immortal hero of a young naval lieutenant named Stephen Decatur, and leave a resonant rhyme between the second and fourth lines of the Marines’ Hymn.

After the war of 1812, Schuylkill Arsenal no longer supplied guns and ammunition to the armed forces, but was committed solely to the manufacture and storage of uniforms and other textile products. During the Civil War, more than 10,000 seamstresses and tailors were hired to make clothing for Union troops. After World War I, operations were moved to new quarters elsewhere in South Philadelphia and renamed the Philadelphia Quartermaster Depot. Today the former grounds of the Schuylkill Arsenal are used for storage by the Philadelphia Electric Company. Only the wagon gate and part of the original wall remain as memorials to the arsenal’s lustrous history.

Quartermaster Captain Lewis

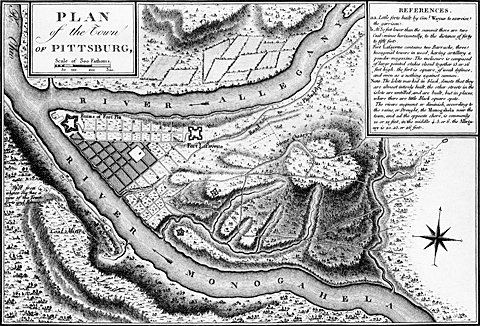

Figure 3

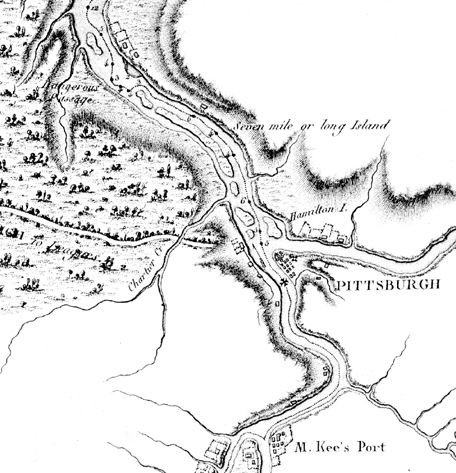

A Journey in North America . . .

Victor Collot’s map of Pittsburgh[3]Georges-Henri-Victor Collot (1750-1805), A Journey in North America, Containing a survey of the countries watered by the Missisippi, Ohio, Missouri, and other affluing rivers; with exact observations … Continue reading

To see labels, point to the map.

Courtesy East Tennessee State University.

“Collot’s References:*

a-a. Little forts built by Genl Wayne to exercise the garrison.

b. At 30 feet lower than the summit there are two Coal-mines horizontally, to the distance of forty to fifti feet.

Fort Lafayette contains two Barracks, three hexagonal towers in a wood, having artillery a powder magazine. the inclosure is composed of large pointed stakes closed together 15 or 16 feet high, the fort is square, of weak defence, and even as a nothing against cannon.

Note, the Islots marked in black, denote that they are almost intirely built, the other streets in the islots [small islands; pron. eye-lut] are untilled, and are built, but in places, where there are little black square spots.

The rivers augment or diminish, according to the rains, or Drought, the Monogahela near the town, and at the opposite shore, is commonly 10 or 12 feet, in the middle 4, 5, or 6, the Allegany is 20, 25, or 26 feet.”

*This map was prepared by Collot’s French cartographer, Joseph Warin, which may account for the errors in English spelling and grammar.

Considering all he had to do to prepare for the expedition, and his small window of time—from 19 April 1803 to 17 June 1803—Lewis was fortunate in that he could rely on a small cadre of Army personnel to help him assemble, pack, and ship his supplies, all of whose names appear throughout the existing records of official transactions. The superintendent of military stores at that time was General William Irvine, whom Lewis had first met in 1794 during the brief climax of the Whiskey Rebellion in Western Pennsylvania, when Meriwether was a 20-year-old Virginia militia volunteer. The official purveyor, or purchasing agent, of public supplies for the government in Philadelphia was Israel Whelan; it was he who placed orders with local civilian craftsmen and shopkeepers for commodities not available in Public Stores. The storekeeper at the Arsenal was George W. Ingels, who was directly in charge of the inventory of government supplies. The fourth key person was William Linnard, the military agent for the Middle Department, whose responsibility was to oversee the transport of all military and medical stores between the Arsenal the far-flung outposts of his district, which extended down the Atlantic Coast from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to Fort McHenry at Baltimore, Maryland, and westward as far as Chickasaw Bluffs, and Forts Massac and Kaskaskia in the Illinois country.

The Harpers Ferry Shipment

Lewis wrote a brief memo on packing, possibly for Linnard’s instruction:

Each article to be weighed separate, and the weight & price extended in the Invoice under the appropriate Head. In packing no regard need be had to the different divisions or classes as specified in the Invoice but pack’d indiscriminately as may be most advantageous, regard being paid to such articles as may be most likely to receive damage. The blankets may be used in the packing for the protection of the goods. Such articles as are taken from the Military stores are to be enter’d in the invoice under their proper heads with weight extend’d & without price.[4]Jackson, Letters, 1:92-93, Memorandum on Packing.

Agent Linnard’s first job for Lewis was to find a wagoner to haul everything Lewis had requisitioned at Harpers Ferry to Pittsburgh—rifles, tomahawks, knives, the frame for his “iron boat,” and other manufactured items. But transportation, whether of freight or persons, was chancy at best in those days, for all sorts of reasons. Lewis measured the extent of his frustration in a short letter to Jefferson. The man Linnard had hired arrived in Harpers Ferry on 28 June, but “determined that his team was not sufficiently strong to take the whole of the articles . . . and therefore took none of them.” It took a week to find a substitute—a man with “a light two horse-waggon” who promised to set out with them on the morning of 8 July 1803. “In this however he has disappointed me,” Lewis groaned, “and I have been obliged to engage a second person who will be here this evening in time to load and will go on early in the morning”[5]Ibid., 1:106-07, Lewis to Jefferson, 8 July 1803. Lewis also told Jefferson the route he would take from Harpers Ferry—to Charlestown (West Virginia), to Frankfort, Uniontown, and “Redstone … Continue reading

Except for the materiel that he shipped direct from Harpers Ferry to Pittsburgh, everything else was to be assembled at the Arsenal and shipped overland to Fort Fayette (originally Lafayette) at Pittsburgh, where it was to be deposited and subsequently loaded onto the waiting barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’). He arranged with William Linnard to provide “a strong and effective team” for the job of hauling 3,500 pounds of supplies and equipment. The single trans-Allegheny road between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh was, as Lewis wrote, “by no means good,” adding, “If a team could be provided with five horses perhaps it would be better.”[6]Ibid., 1:53-54, Lewis to William Linnard, 10 June 1803.

On 25 March 1804, Linnard submitted his invoice for $226.98. The military rate of 0.065 cents per pound was considerably lower than the commercial rate, which was then about 0.08 cents per pound. For the distance covered, 415 miles, the rate came to 55 cents per mile.

Fort Fayette to Wheeling

Unfortunately, the boat Lewis had ordered specially built was not ready until the end of August, by which time the Ohio River was at a record low—so low that Lieutenant Moses Hooke, the commander at Fort Fayette, mentioned in a letter to Linnard, “I am fearfull he will not be able to prossecute his voyge untill it rises, notwithstanding he took the precaution to send two Waggon loads of his goods by land to Wheelin.”[7]Jackson, Letters, 1:119, Moses Hooke to William Linnard, 2 September 1803. Lt. Hooke had recently succeeded Amos Stoddard, who was posted temporarily to Kaskaskia in the Illinois country, and was to … Continue reading Evidently those two wagons were smaller and lighter than Conestogas. Lt. Hooke forwarded to Linnard the bill for that 65-mile overland haul, as well as the cost of a pilot to assist Lewis down the Ohio as far as the Falls of the Ohio at Louisville.

Lewis left Pittsburgh aboard the barge on 31 August 1803, and reached Wheeling on 6 September 1803, where he found his shipment—which he had consigned to a merchant named Caldwell—in good order. From there on, despite the lateness of the season, he had expected the river would become easier to navigate. Instead, he was compelled to buy a pirogue to help carry the increased load, and to lighten the barge as much as possible, to avoid being permanently stalled by gravel bars—riffles, as they were called locally—that were sometimes covered by as little as six inches of water.

Notes

| ↑1 | Pronounced “school-kill,” often “skoo-kl.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Grays Ferry, by then upgraded to a floating bridge, was one of three crossings of the Schuylkill River on Philadelphia‘s south side, and the one nearest the Delaware River. Meriwether Lewis crossed when he set out for Pittsburgh in June 1803. |

| ↑3 | Georges-Henri-Victor Collot (1750-1805), A Journey in North America, Containing a survey of the countries watered by the Missisippi, Ohio, Missouri, and other affluing rivers; with exact observations on the course and soundings of these rivers; and in the towns, villages, hamlets and farms of that part of the new-world; followed by philosophical, political, military and commercial remarks and by a projected line of frontiers and general limits. Illustrated by 36 maps, plans, views and divers cuts. Paris, 1826. In 1796 Pierre Adet, the French minister to the U.S., being concerned that the U.S. might enter the war on Britain’s side, in which case France would need accurate understanding of the Mississippi and Missouri valleys. He asked Collot, who had distinguished himself fighting with the Americans during Revolution, to reconnoitre the Ohio, Mississippi and Missouri valleys. Collot, with French cartographer Joseph Warin, two Canadian voyageurs and three American boatmen, in a flatboat, descended the Ohio and Mississippi to New Orleans where the Spanish arrested and briefly imprisoned them. Upon his release Collot returned to France, where he died in 1805. His manuscripts, maps, and drawings were published in two volumes in 1826, 300 copies in French and 100 in English. American Journeys, http://www.americanjourneys.org/aj-088a/summary/index.asp. Accessed 12 September 2007. |

| ↑4 | Jackson, Letters, 1:92-93, Memorandum on Packing. |

| ↑5 | Ibid., 1:106-07, Lewis to Jefferson, 8 July 1803. Lewis also told Jefferson the route he would take from Harpers Ferry—to Charlestown (West Virginia), to Frankfort, Uniontown, and “Redstone old fort” to Pittsburgh. Lewis arrived at his destination on 15 July; the wagon from Harpers Ferry got there on the 22nd. Ibid., 1:112, Lewis to Jefferson, 22 July 1803. |

| ↑6 | Ibid., 1:53-54, Lewis to William Linnard, 10 June 1803. |

| ↑7 | Jackson, Letters, 1:119, Moses Hooke to William Linnard, 2 September 1803. Lt. Hooke had recently succeeded Amos Stoddard, who was posted temporarily to Kaskaskia in the Illinois country, and was to take charge of the first military headquarters at St. Louis following the transfer of Upper Louisiana to the U.S. Pending William Clark‘s reply to the offer of the co-captaincy he had extended, Lewis seriously considered Hooke, a 26-year-old lieutenant in his own 1st Infantry Regiment, as potentially a second-in-command. |