Newspapers

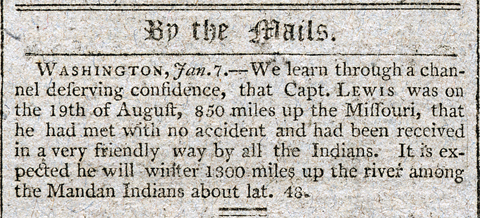

Publications that attempted to tell the story of Lewis and Clark were being printed before Lewis and Clark had even returned from their trans-Mississippi exploration. As Lewis and Clark made their way up the Missouri, they kept in constant contact with the Atlantic states through letters delivered by traders headed downriver. For example, on 20 November 1804, Auguste Chouteau delivered a letter to Thomas Jefferson describing the early progress of the expedition, sent to him by Lewis in August of the same year.[1]Doug Erickson, et al. “Matthew Carey: First Chronicler of Lewis and Clark,” We Proceeded On 29 (2003): 29. See also Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 2 vols. … Continue reading The contents of these letters were widely disseminated, and spread like wildfire in newspapers from Louisville to Boston.

John Carey’s Account

Occasionally the accounts were expanded and given considerable conspicuous prominence in published form. In 1806 Matthew Carey included a paragraph about Lewis and Clark in his thirteen-page addendum to the American edition of John Newbery’s venerable Compendious History of the World, which first appeared in London in 1763. Although brief, Carey’s account of the expedition glorified the promise of the expedition, and gave early hints of American entitlement to the far western territory of North America. This entitlement was so prevalent that it was eventually given the formal name, “Manifest Destiny,” in 1845 by a Democratic Party journalist, John L. O’Sullivan.

Carey’s account reads as follows:

The extensive region of Louisiana has excited a laudable attention in the President of the United States, as a field of investigation worthy of the politician and philosopher. To explore this wilderness, and to obtain some better knowledge than we yet possess, of its various productions and inhabitants, Major [sic] Lewis and his company are now travelling at the public expense. They have extended their researches many hundred miles up the great river Missouri, and are still pursuing their journey to the west and northwest. This enterprise cannot fail to produce some very important discoveries, useful in the highest degree to the interest of commerce; nor can it occasion any just offence to the governments of Great Britain or Spain, if conducted with that prudence which we have a right to expect from the temperate councils of Mr. Jefferson.[2][Mathew Carey], A Compendious History of the World: From the Creation to the Peace of Amiens 1802. (Philadelphia: Printed for Benjamin Johnson), 237.

Carey was an avid supporter of Jefferson, and he fully embraced the president’s strategic decision to purchase Louisiana. The final sentence makes clear his view that the Louisiana Purchase would be crucial to the economic future of the United States despite the conflicting interests of European powers. Without knowing the results of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Carey was limited in his ability to laud the explorers, but his short statement gave the Expedition a prominent place in world history, and in a sense laid out the parameters within which future writers would laud the explorers.

Jefferson’s 1806 Report to Congress

After wintering at the Knife River Villages in North Dakota, Lewis and Clark sent a cache of reports, letters, and specimens to President Jefferson. These materials formed the basis of Jefferson’s February 1806 report to Congress. Rarely has a government report received such widespread attention. Portions of the report were reprinted as broadsides and special newspaper editions. The whole report was reprinted for popular consumption by Hopkins & Seymour of New York, just months after its release by the government. It was also printed in editions for large society crowds in London and for frontier politicians and scientists in Natchez, Mississippi.

These various forms of the first official and incomplete account of Lewis & Clark supplemented the previous newspaper reports about the expedition as a second source of information for eager publishers like Zadok Cramer of Pittsburgh, and the numerous rogue publishers of Philadelphia and Baltimore, who surreptitiously compiled eight or nine fabricated accounts of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.[3]Doug Erickson et al., Literature of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Portland, Ore.: Lewis & Clark College, 2003), 119-143.

Patrick Gass’s Journal

Cramer assessed this popular body of literature and wisely predicted a rich market for the complete Lewis and Clark story. In conjunction with David M’Keehan, Cramer purchased the rights to Patrick Gass‘s journal, and quickly prepared the text for publication. Gass’s journal was the first complete account of the expedition, and as such, it was an immense success. Issued less than year after the return of the Corps of Discovery in 1807, Cramer and M’Keehan were able to capitalize on the sale of one-time publication rights to J. Budd of London, and Mathew Carey of Philadelphia, who published three illustrated editions of the text. Cramer also used portions of the text as an appendix to his Ohio River Navigator starting in 1814, ensuring that even readers looking for something as mundane as a navigation guide would have access to the story of Lewis and Clark.

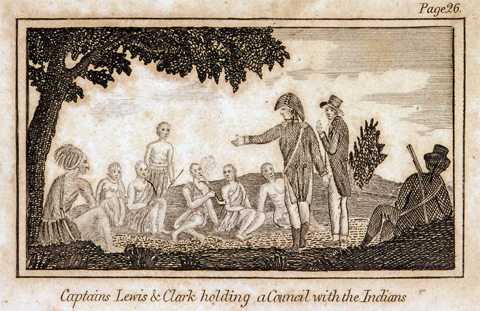

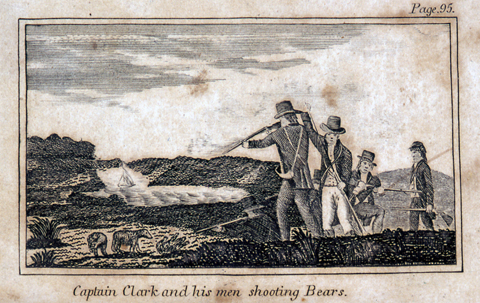

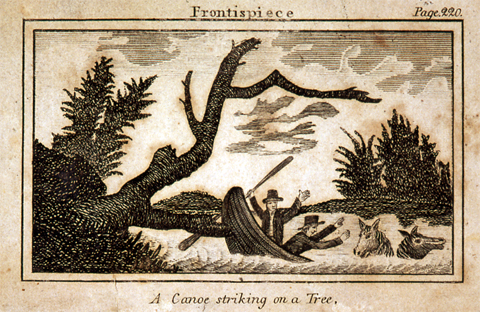

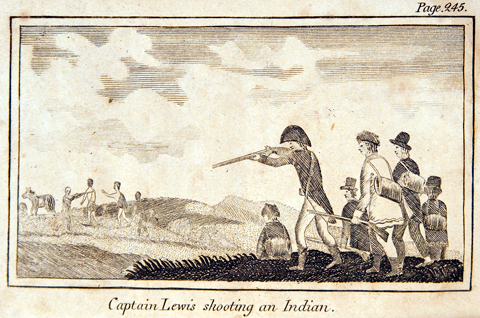

Copperplate engravings from Journal of the Voyages and Travels of a Corps of Discovery by Patrick Gass, 3rd edition, 1810

Fort Mandan

The following is the manner in which our huts and fort were built. The huts were in two rows, containing four rooms each, and joined at one end forming an angle. When raised about 7 feet high a floor of puncheons or split plank were laid, and covered with grass and clay, which made a warm loft. The upper part projected a foot over and the roofs were made shed-fashion, rising from the inner side, and making the outer wall about 18 feet high. The part not inclosed by the huts we intend to picket. In the angle formed by the two rows of huts we built two rooms for holding our provisions and stores.

Council Bluff

Captain Lewis and Captain Clarke held a council with the Indians, who appeared well pleased with the change of government, and what had been done for them. Six of them were made chiefs, three Otos and three Missouris.

Near the Marias River

In the evening we went towards the river to encamp, where one of the men having got down to a small point of woods on the bank, before the rest of the party, was attacked by a huge he-bear, and his gun missed fire. We were about 200 yards (ca. 183 m) from him, but the bank there was so steep we could not get down to his assistance: we, however, fired at the animal from the place where we stood and he went off without injuring the man.

Long Camp

Two of our men in a canoe attempt to swim their horses over the river, struck the canoe against a tree, and she immediately sunk; but they got on shore, with the loss of three blankets, a blanket-coat, and some articles of merchandize they had with them to exchange for roots. The loss of these blankets is the greatest which hath happened to any individuals since we began our voyage, as there are only three men in the party, who have more than a blanket a piece. The river is so high that the trees stand some distance in the water.

Willow Run, near the Falls of the Missouri

In the evening the man who had started to go to the other end of the portage, returned without being there. A white bear met him at Willow creek, that so frightened his horse, that he threw him off among the feet of the animal; but he fortunately (being too near to shoot) had sufficient presence of mind to hit the bear on the head with his gun; and the stroke so stunned it, that it gave him time to get up a tree close by before it could seize him. The blow, however, broke the gun and rendered it useless; and the bear watched him about three hours and went away; when he came down, caught his horse about two miles distant and returned to camp. These bears are very numerous in this part of the country and very dangerous, as they will attack a man every opportunity.

Two Medicine River

On the evening of the 26th Captain Lewis and his party [only three men, not five] met with eight of those Indians, who seemed very friendly and gave them two robes. In return Captain Lewis gave one of them, who was a chief, a medal; and they all continued together during the night; but after break of day the next morning, the Indians snatched up three of our men’s guns and ran off with them. One Indian had the guns of two men, who pursued and caught him; and one of them killed him with his knife; and they got back the guns. Another had Captain Lewis’s gun, but immediately gave it up. The party then went to catch their horses, and found the Indians driving them off; when Captain Lewis shot one of them, and gave him a mortal wound; who notwithstanding returned the fire, but without hurting the Captain. So our men got all their own horses but one, and a number of those belonging to the Indians, as they ran off in confusion and left every thing they had.

Fiction

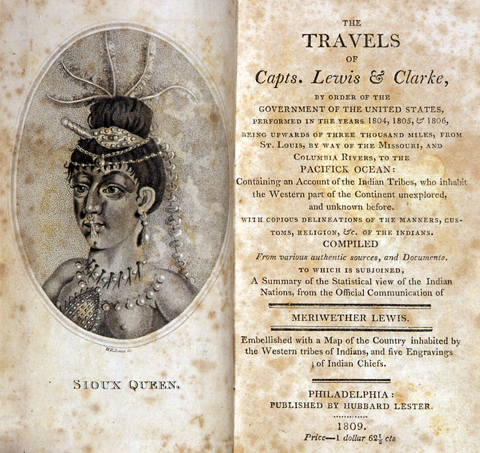

Figure 9

The Travels of Capts. Lewis & Clark

Special Collections and Archives, Watzek Library, Lewis and Clark College, Portland, Oregon.

Frontispiece and title page to the purported account of the Lewis and Clark expedition published by “Hubbard Lester” in 1809. Nicholas Biddle‘s two volume paraphrase of the two captains’ manuscript journals was still five years away.

Other publishers with less capital than Cramer chose to provide what amounted to a fictitious account of Lewis and Clark. The first publisher/one known to issue such a publication was the pseudonymous Hubbard Lester. In 1809 Lester borrowed newspaper accounts, the 1806 report to congress, and pieces of early exploration narratives by Alexander Mackenzie and Jonathan Carver to present a book that would appear at first glance to be the complete and official account of the expedition.

Actually, “Hubbard Lester” had no permission to use any of the texts included in his book, and it is little surprise that he published under a pseudonym.

Other publishers, including James Sharran, William Fisher, Anthony Miltenberger, Philip Mauro, and a pair of German-American printers, Mathias Bartgis and Jacob Stover, borrowed Lester’s text to cash in on the Lewis and Clark story. During nearly half a century there were in all at least eight or nine counterfeit editions, each of which, as Paul Russell Cutright expressed it, was “a dark and uncomely smudge on the well-favored countenance of the fourth estate, and another illustration of what Sophocles had on his mind earlier than 400 B.C. when he wrote in Antigone, ‘For money you would sell your soul.'”[4]Paul Russell Cutright, A History of the Lewis and Clark Journals (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976), 33.

What is most surprising about these publications is that they continued to find an audience, even in the wake of numerous editions of Gass’s journal and the official account of the expedition compiled in 1814 by Nicholas Biddle and Paul Allen. It is clear that the Lewis and Clark story had considerable popularity during the first fifteen years of the nineteenth century, and inexpensive publications like Lester’s, which was priced at $1.62 (the equivalent of $25-28 today); in contrast, the Biddle-Allen edition sold for $6.00 per set in 1814, helped promote the story to audiences beyond the American and European elite.[5]In contrast, the authentic Biddle-Allen edition sold for $6.00 per set in 1814, the equivalent of $71-74 today. Price comparisons derived from economic conversion formulas at … Continue reading Even more astonishing was the fact that the spurious accounts kept coming until the last one was reprinted in 1846, thirty-two years after the Biddle paraphrase appeared.

Misinformation

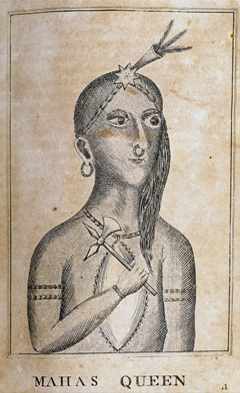

Two of the five caricatures of Indians in the 1810 edition of The Travels of Capts. Lewis & Clarke. The others were of a “Mahas [Omaha] Chief,” a “Sioux Warrior,” and a “Serpentine [Snake] Chief.” Apparently, all five were calculated to show that Indian people “looked different.”

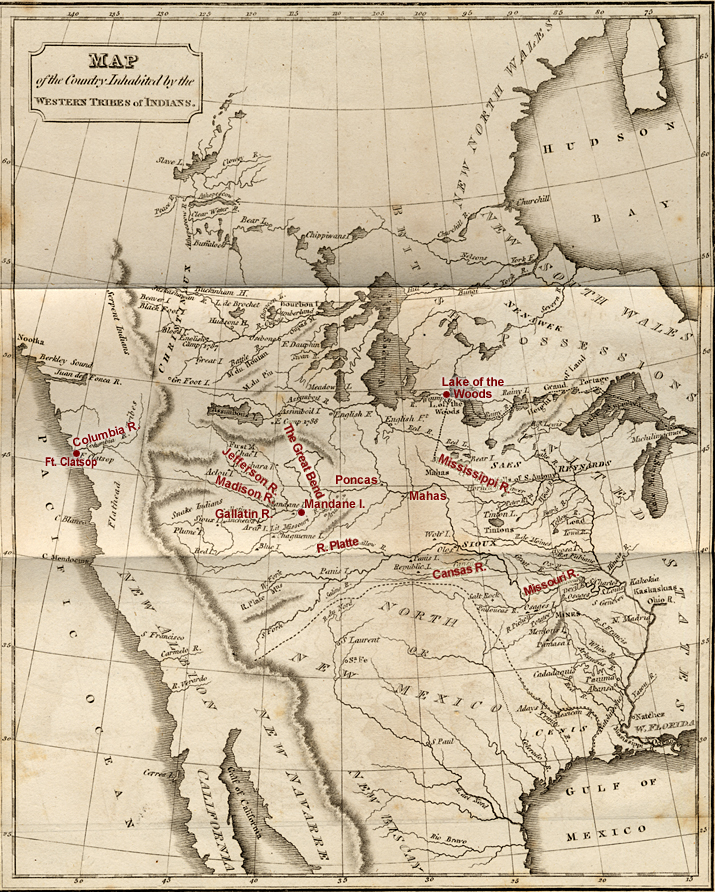

Pity the traveler relying on this map. Lake of the Woods is located hundreds of miles from its actual location and the Poncas live to the west of the Omaha (Mahas) instead of to the north. Fort Mandan and the Great Bend of the Missouri River appear near the Three Forks of the Missouri with the Madison and Gallatin rivers flowing west. Any traveler who tore this map out of Lester’s apocryphal book and then used it as a travel guide probably didn’t live to tell the tale.

—Kristopher Townsend, ed.

The Biddle Edition

The final piece in the early corpus of Lewis and Clark literature was the previously mentioned, official two-volume narrative of the expedition compiled by Nicholas Biddle and Paul Allen, and published in Philadelphia in 1814. Having originally made it the responsibility of Meriwether Lewis, now Thomas Jefferson solicited the help of Nicholas Biddle to usher the work into print. By all accounts Biddle worked diligently to provide an accurate narrative; he met and corresponded with Clark, interviewed expedition member George Shannon, and examined all of the known manuscript materials. The result was an accurate, concise, and at times artistic narrative that served as the standard authoritative Lewis and Clark text until 1904. Even today, the Biddle/Allen text is considered an authoritative check on the journals because of Biddle’s first-hand access to information provided by expedition members. In addition to Biddle’s text, the edition included Clark’s map of the American West, the standard for the northern portion of what is now the United States until the 1830s.

Despite the historical importance of this publication, American reader response was tepid. Major intellectual American journals like the Port Folio and the Analectic Magazine published reviews that were generally favorable, but they consistently lamented the lack of a volume dedicated to scientific discovery.[6]Erickson, ibid., 173. It would appear that the American public already knew the story, but was hungry for data. This is further supported by the fact that most surviving sets of the narrative lack Clark’s map. Anecdotal information suggests that these maps were torn out and used as a guides by subsequent trans-Mississippi travelers with little concern for the actual text of the book.[7]See Lester J. Cappon, History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark Philadelphia, Published by Bradford and Inskeep, 1814. A Census of Extant Copies in Original Boards with … Continue reading Although the Biddle/Allen text was reprinted numerous times in many languages, unlike the Gass publication, which was published in four American editions in five years, the Biddle/Allen narrative was not reprinted in the United States until 1842, when extensive migration to the Pacific Coast rendered the text useful as a guide. By 1814, American readers had moved on from Lewis and Clark.

Despite the apparent domestic failure of the Biddle/Allen edition, it was an important text for fiction writers and naturalists of the nineteenth century who repeatedly returned to the text for inspiration. The official account of the expedition was so compelling, it inspired painters, creative writers, and travelers, who together constructed a perception of the American West couched in sentiments, ideas, and terminology provided by Lewis and Clark.

Notes

| ↑1 | Doug Erickson, et al. “Matthew Carey: First Chronicler of Lewis and Clark,” We Proceeded On 29 (2003): 29. See also Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:218; Moulton, Journals, 1:495. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | [Mathew Carey], A Compendious History of the World: From the Creation to the Peace of Amiens 1802. (Philadelphia: Printed for Benjamin Johnson), 237. |

| ↑3 | Doug Erickson et al., Literature of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Portland, Ore.: Lewis & Clark College, 2003), 119-143. |

| ↑4 | Paul Russell Cutright, A History of the Lewis and Clark Journals (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976), 33. |

| ↑5 | In contrast, the authentic Biddle-Allen edition sold for $6.00 per set in 1814, the equivalent of $71-74 today. Price comparisons derived from economic conversion formulas at http://www.measuringworth.com/uscompare/ |

| ↑6 | Erickson, ibid., 173. |

| ↑7 | See Lester J. Cappon, History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark Philadelphia, Published by Bradford and Inskeep, 1814. A Census of Extant Copies in Original Boards with a Preface by Alfred C. Berol (New York: Columbia University Libraries, 1970) |