Note: What follows is a transcript of a lecture by the author, which he delivered in October 2006 at a symposium on The Legacy of Lewis and Clark at Lewis and Clark College in Portland, Oregon. The author had served as a scholar-in-residence at Lewis & Clark College for that institution’s observance of the bicentennial, and was the principal scholar in the college’s collaboration with Oregon Public Broadcasting that produced the 13-part radio documentary The Unfinished Journey.—J.M., Ed.

Legacy is a very slippery sort of term. How do you define the legacy of any historical event? How do you measure it? It’s easier to opinionate about legacy than to think about it, and the more you think about it the more difficult it becomes to pin down the legacy of a transient event like the 28-month Lewis and Clark Expedition. Lewis and Clark on average spent fewer than two days with each Indian culture that they met. There were some notable exceptions—the Mandan and Hidatsa in today’s North Dakota, the Clatsops and the Chinooks on the lower Columbia, the long camp with the Nez Perce on the return journey. But for the most part, Lewis and Clark would meet a tribe, have a day or two or three with it, and move on.

There’s a paradox in the way that we think about Lewis and Clark because we examine it two hundred years after the fact when the Expedition has taken on monumental importance as an American saga, as a national origin story, as mythology, and as a part of the American narrative. We know how the story comes out, which is more than Meriwether Lewis or Thomas Jefferson knew at any given moment between May 14, 1804 and September 23, 1806. We know what followed, and we know that we live on lands that Lewis and Clark in some sense helped to open for Anglo-American settlement. That means that we detect a heavy burden of consequence that may not actually constitute historical legacy. Our awareness of consequence encourages us to overload Lewis and Clark with a moral burden that they may not deserve to bear.

Let me just give you one very fascinating example. When I was working on a book on Lewis and Clark in North Dakota, I saw a Mandan winter count. Now, Lewis and Clark spent more time with the Mandan and the Hidatsa than with any other people, and they had their most successful relations with Indians amongst the Mandan and the Hidatsa. According to James Ronda, their best ethnographic work was done in what’s now North Dakota. There’s a Mandan winter count on a buffalo skin. It’s a calendar, it’s an ideogrammatic chronology of the Mandan year when Lewis and Clark came through.

There are fifty or sixty icons on this robe: the grass fire, the big buffalo hunt, the skirmish with the Shoshone. And then there’s this little tiny icon of bearded white men. That’s not how we see it. We want that robe to exhibit a few little perimeter icons of traditional Mandan-Hidatsa activities and then a huge and dramatic depiction of the advent of Lewis and Clark in the center, with the caption, “We’re here! And everything is going to change forever now. History has arrived at the Mandan villages.” From a native point of view, Lewis and Clark were travelers who came through, spoke somewhat aggressively and pompously in a language that probably didn’t get translated very well, and then moved on leaving some material behind—some beads, some sovereignty tokens, some genetic material. But, from a native point of view, in the short term Lewis and Clark were transitory figures—a surprising group of surprising large size that came through and took itself very seriously, and then left, and did not return in the years following the Expedition.

On the return journey Lewis and Clark didn’t meet all of the same peoples that they had met on the outward-bound journey. So if you look at the expedition, say, from an Arikara point of view, they spent a couple of days with the Arikara in early October 1804, and then they moved on. And then on the return journey, in August 1806, they stopped for one day with the Arikara. Now the Arikara had good reason to remember Lewis and Clark because Lewis and Clark sent an Arikara chief off to Washington D.C. with the interpreter Joseph Gravelines as one of the delegations Jefferson had requested in his June 20, 1803, instructions. That Arikara chief, Arketarnarshar, or Too Né (Eagle Feather), didn’t come back—he died of natural causes in Washington D.C. So that got the attention of the Arikara in a way that Lewis and Clark wouldn’t have under other circumstances. Just how much Eagle Feather’s death in D.C. had to do with the hostility of the Arikara to white American visitors in the next generation is hard to assess. We know that as late as the expedition of Prince Maximilian in 18333, the Arikara were still regarded as unswervingly hostile toward Americans and, for that matter, most other white visitors. I’m just trying to ask you to do what James Ronda does so brilliantly, which is to reverse the lens for a moment and think about legacies from a native point of view and to try to dispossess ourselves of the heavy retrospective significance we attach to Lewis and Clark because we’re here, and we’re commemorating, and we know all that followed.

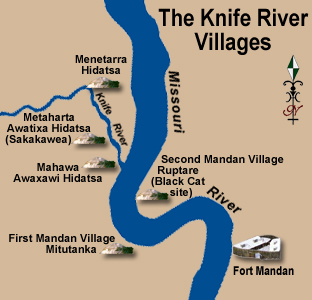

Lewis and Clark arrived in the Mandan-Hidatsa world on October 26, 1804 (Figure 1). They stayed until April 7, 1805. On November 2 they started to build what they would call Fort Mandan. At this point they were just making preliminary contact with the Mandan people. They hadn’t yet really met the Hidatsa people. The whole population of these five villages was about 4,000 people. It was the largest urban center on the Northern Great Plains. It was a North American trade mart located near the geographic center of the continent.

Lewis and Clark were aware of the Mandan and Hidatsa villages from previous travelers’ reports. They hadn’t planned to winter with the Mandan. They were behind schedule. In fact, they had planned to get all the way to what Clark called the Rock Mountains, but they had fallen behind schedule for lots of interesting reasons. Now they stopped for really one reason only—the river froze. The highway was closed. If you travel on the interstate highways, say, in Wyoming today, you see those gates that go down in a blizzard, and that’s it, they close the road. It didn’t used to be that way. It used to be that you could go out and perish if you wanted to. But in early November 1804, the Missouri river closed, the river froze, and one week later Lewis and Clark built Fort Mandan. When the river thawed, when ice broke up in the last days of March 1805, Lewis and Clark left immediately. The highway was open again.

Corn Mills and Canadians

A Gift from the President

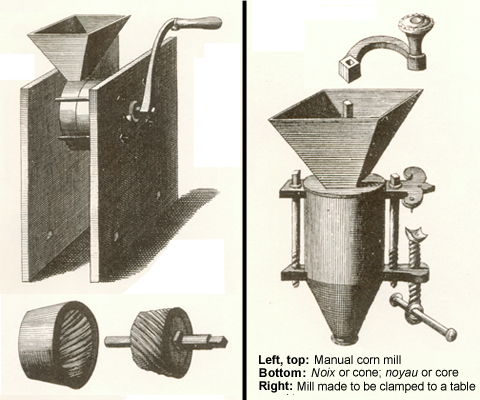

In addition to the portable hand-operated corn mill Lewis took along for the company’s use, at President Jefferson’s suggestion he bought two more to give away to Indians. The captains presented one of them to the Mandans (see Figure 2). What became of the other two is still unknown.

Aside from what they were made of (steel and cast iron), their weights (the company’s mill weighed 20 pounds, the gift mills about 25 pounds each), and their costs ($9 to $10 each), there appears to be no hope of determining exactly what the three mills looked like. The two examples pictured above are from the great Encyclopédie edited between 1751 and 1780 by two Frenchmen, Denis Diderot and Jean d’Alembert.]

One of the “gifts” Lewis and Clark carried in their boats was a type of corn mill. President Jefferson was a great agrarian. You can imagine him before the expedition thinking about the symbolic possibility of bestowing corn mills on appropriate Indians. When you meet a promising Indian tribe—Indians who might come around to our way of seeing the world and our way of doing things—give them this corn mill because this is a symbol of sedentary agriculture. There’s a little irony in this because of course the Mandan and the Hidatsa were agriculturalists long before Jefferson was born, long before the United States was born. They were North Dakota’s first farmers. They had constructed North Dakota’s first grain storage facilities underground, and they were so rich that tribes from all over North America came there to trade. Mandan and Hidatsa corn became the basis of their success as economic entrepreneurs on the Northern Great Plains. For Lewis and Clark to give the native world’s premier farmers a corn mill is not perhaps the most geopolitically intelligent gesture that they might have made. And you’ll see what happens—it’s a very interesting story. Clark writes, “a Iron or Steel Corn Mill which we gave to the Mandins, was verry Thankfully recived.” That’s all we ever learn from Lewis and Clark about the corn mill.

Fortunately, while Lewis and Clark were in North Dakota that year, Canadians were there too, from the Northwest Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company. They were moving back and forth between the Canadian trade forts on the Assiniboine River and the Mandan and Hidatsa villages. Unlike Lewis and Clark, who built a fortified compound outside of the Mandan and Hidatsa world, the Canadians embedded themselves individually in the villages. They would go stay with families.

The Mandan and the Hidatsa had a very interesting economic adoption system in which they would temporarily adopt a visitor, even one from an enemy tribe, as a family relative. That would give the stranger a kind of passport to trade safely within the Mandan and the Hidatsa world. The Canadians would embed themselves in the village, while Lewis and Clark held themselves apart, even aloof. They wanted to keep a distance from village life. It was a very different experience for the Canadians than for Lewis and Clark. The two white groups did not like each other very much. The Canadians were upset that the Americans were shoving their weight around, because Lewis and Clark immediately called the Canadians in and said, in effect, “You can trade here, even though it’s now our territory, but you cannot proselytize. You cannot give Indians sovereignty tokens. You cannot bad mouth the United States. No flags. No peace medals. No coins with George III on them. You can trade kettles and beads but don’t issue sovereignty tokens of any sort.” And the Canadians said,”Okay, we’ll abide by your rules. We weren’t issuing sovereignty tokens anyway.” The historical evidence proves that the Canadian traders were undermining American sovereignty among the Mandans and Hisatsas, partly because the issues that were implicit in the Treaty of 1783 had not been fully cleared up either by the Jay Treaty (1794) or the Louisiana Purchase; and partly because the Canadians were not willing to abandon their lucrative trade relations with the earth-lodge peoples. Those trade relations were inextricably linked to sovereignty tokens and other “gifts” that bore nationalistic significance.

There’s another legacy consideration. The Canadians knew all they had to do was wait—the pushy representatives of the United States would soon leave. The Canadians knew that the Americans were making big claims about the St. Louis trade corridor, but they would soon be heading west towards the Pacific, and it was unlikely that American traders from St. Louis would be visiting the villages anytime soon. The Canadians were pretty sure they could maintain their trade monopoly on the Upper Missouri, at least for the next few years. So the Canadians made a show of complying with the expedition’s firm sovereignty demands because they knew it was in their interest to avoid an international incident, and they rightly calculated that Lewis and Clark were transients. Basically, all of the peoples that Lewis and Clark met banked on the fact that they were transients and therefore they didn’t have to take them too seriously.

Here’s the journal of Alexander Henry, a Canadian, and kind of a grumpy one, who was a frequent visitor to the Mandan-Hidatsa villages. In 1806, two years after the captains bestowed the corn mill on the Mandan people, Henry wrote, “I saw the remains of an excellent large corn mill, which the foolish fellows had demolished on purpose to barb their arrows and other similar uses. The largest piece of it which they could not break nor work up into any weapon they have now fixed to a wooden handle and make use of it to pound marrow bones to make grease.” This is a great moment in the Lewis and Clark story. It’s a great legacy moment because of course Lewis and Clark had handed over this symbolic agrarian corn mill with a Jeffersonian legacy in mind. They didn’t know how the story would come out, and they would not have appreciated how the Mandan responded to their generosity. Alexander Henry provided a thoroughly Eurocentric analysis, and he probably spoke for Lewis and Clark: These Mandans are fools. They’ve broken this wonderful device—this civilizational device—to make arrow points.

Well, what if we reverse the lens on this story as James Rhonda wants us to do. Do you think the Mandan knew how to grind corn? Well of course! They had been grinding corn on the Great Plains for hundreds of years. They had mortars and pestles that were perfectly crafted for the milling they engaged in on a nearly daily basis. Corn grinding they have native technology to accomplish. At the same time, they’re metal-starved. They were a people without metallurgy who craved any piece of metal they could get their hands on. They wanted axes and grinders with which to process buffalo robes, and of course they wanted knives and arrow points. They didn’t need an agricultural instrument; they wanted that metal for more important strategic uses. And so they quite intelligently broke it up, and the only piece they couldn’t break up they found another use for—to pound grease. So they actually provided what might be called “value added” to the corn mill. Poor Henry couldn’t see it, but it was a perfectly appropriate thing for the Mandan to have done.

A Gift from the President

This object was recovered by archaeologists in 1950 from the site of one of the Mandan villages (see Figure 1). It is thought to have been the revolving core or “runner” with its teeth either filed or rusted off. The head end, at left, shows evidence of having been worked on with a hammer, perhaps in a Mandan’s effort to make it into a more practical object.

The physical legacy of this little parable, the handle of the corn mill, the thing the Mandan couldn’t break up, almost certainly now rests in the vaults of the Fort Mandan Interpretive Center north of Bismarck, North Dakota. The curators at Fort Mandan have what they are quite certain is that piece. That lasted; the rest of the metal is gone.

Another way to look at this whole question of legacy is to ask: What did Lewis and Clark think their legacy would be? When they got back to St. Louis on September 23, 1806, what did they see as their legacy? They wrote letters, each of them. Lewis wrote a letter to Thomas Jefferson, an official letter from an army captain to his boss, to the commander in chief, a protégé to his mentor; and Clark wrote a letter to his brother Jonathan. Both of those letters are fascinating documents. Most of what they wrote in these letters has nothing to do with Indians whatsoever. What they wrote about is the river infrastructure of the American Northwest. Both of them spent the majority of their time saying, “We’ve essentially done what you asked us to do. We’ve found the best water connection between St. Louis and the Pacific.” They both admit that the route they established is not perfect, there is that 340-mile portage, 120 nearly impenetrable, with 60 miles of mountain terrain covered with eternal snow. “And by the way, the Rockies are not as low as the Appalachians, Mr. Jefferson.” But they make the best of it; especially Lewis who is just desperate to say, “It doesn’t really look the way you might’ve hoped, there’s no Cumberland Gap, but we can make it work. We can buy horses from the Indians. Cheap!”

In those first letters, Lewis and Clark spend a lot of time on trail issues and they spend a lot of time on the commercial possibilities of Upper Louisiana. Lewis particularly says, “Alright, now that we’ve opened it, I’m here to tell you that there’s an infinite number of beaver out there, and those beaver are going to be harvested by the British Empire and its commercial subsidiaries, unless we take charge of this and engage in fundamental economic competition with the British. This will require government grants.” So he’s telling Jefferson, the strict constructionist, the penny-pinching Jefferson, that if we’re going to get into the fur trade—which we should—our government is going to have to subsidize it. We’re going to have to return to a mercantilist economy if we’re going to compete with the British. That’s the main business of these initial letters to the white community back home. At no point, in these preliminary reports, did they say, let me describe the complexity of Native American culture, or the potential sovereignty questions that we are going to face, or the potential resistance that we are going to meet as we develop the wilderness. They do acknowledge that to get started in the fur trade, the United States is going to have to pacify the lower Missouri tribes, particularly the Sioux.

Unfortunately, the captains do not go into detail about the legacies that we would find most interesting. They thought their legacy was that they had opened the road to the commercial extraction of the American Northwest and the American competitiveness against particularly Great Britain. They had mapped the landscape where all this would take place. They had made significant scientific discoveries. They had filled in the blank spaces on the map. They were bringing back specimens.

But of the legacy that we of the bicentennial might hope that they would consider for themselves, there’s almost no word whatsoever in this set of letters. In fact, the sense you get from Lewis and Clark is that Indians are not much more than a challenging, an intriguing impediment to the commercial future of the Northwest. In other words, they were not thinking what we would think—what’s going to be the relationship between these two very different peoples? How are white-Indian relations in the American West going to get worked out? For Lewis and Clark it was simple: We’ll need them in the fur trade and we’re going to have to chasten a few of them if we expect this to work.

Markets and Mandans

Figure 3

“Mandan Village”

Karl Bodmer (1809–1893)

Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

Plate 49 from Prince Maximilian of Wied, Travels to the Interior of North America, 1843-44

There’s another legacy document that I want to point to which comes in the so-called Mandan Miscellany. During the winter at Fort Mandan, Lewis and Clark wrote the only true government report that they would ever write. It’s really a fascinating document. Unfortunately, it has been almost completely ignored in the Lewis and Clark literature. It deserves intense study because it is a quintessential Jeffersonian document. It consists of charts of rivers; an Estimate of Eastern Indians in which they name the tribe, then the names the tribe is known by among other tribes and by white people nearby; they talk about where the best possible trade mart or fort sites would be located; what that tribe can produce by way of pelts or other commodities that white people might want; what their exchange rate is. It’s a fascinating chart that Lewis and Clark put together over the course of the winter at Fort Mandan. Basically it’s a perfect Jeffersonian document—Jefferson loved nothing so much as a big chart. If Jefferson could’ve lived to see Excel, he would’ve been in heaven because he just loved to gather and enter data and sort it out and see how it all fits. Jefferson was an admirer of FranAcis Bacon, who advocated the patient gathering of data, then careful sorting, before any attempt at synthesis was made. Jefferson’s chosen agents of discovery, Lewis and Clark, made this immense chart. It’s really one of the great documents of Lewis and Clark.

They’re basically saying, here is a list of the Indians and here’s how we’re going to build our economy by knowing what they have (in surplus) and what they want and where they want to trade and how they name themselves and who their enemies are and what rivers they’re on and so on. Unfortunately that document can never be reproduced properly. It always appears in a corrupt form in Lewis and Clark books because when it is turned to print it becomes too unwieldy to be displayed as a chart; and when it’s not a chart, when the information is spread across more than sixty pages in a text, it makes much less sense. One of the things in this very important interim report, the Mandan Miscellany, is a small chart produced by William Clark, which lists the places where military fortifications are going to have to be built on the upper Missouri in order to fulfill America’s geopolitical plans. Clark is creating a display of “The Number of Officers & Men for to protect the Indian trade and Keep the Savages in peace with the U.S. and each other . . . if Soldiers act as Boatmen & Soldiers.” Clark’s view is not that the United States can simply send out entrepreneurial fur traders, to fan out across the country, and that they will thereby achieve economic success. Clark’s view is if the United States wants to compete successfully in the fur trade, it will have to engage in an occupation of the Upper Missouri. He says the number of officers and men required for this occupation will be at least 700 at 12 locations. There’s a Lewis and Clark legacy that we don’t hear much about, and yet the pragmatic Clark would have regarded this as absolutely essential to any realistic plan for safe trade in the region. You can read the late Stephen Ambrose’s magisterial Undaunted Courage, you don’t hear about the post-expeditionary occupation plan that Clark has in mind for this. I find that it to be a really interesting and really chilling document.

Here’s another one. This is from November 18th, 1804. They’ve now built Fort Mandan; it’s not quite done yet, but it’s substantially built and they’re trying to make contact with the leaders—at least as they understand the concept of leader—of the five villages. There are two Mandan and three Hidatsa villages in the vicinity of the mouth of the Knife River. That’s something of an oversimplification, but it’s an oversimplification we can live with. Three Hidatsa, two Mandan. The Hidatsa are farther away, the Mandan are closer to the Fort. The Hidatsa are more skeptical of Lewis and Clark; the Mandan are more friendly. In fact, from a kind of modern anachronistic point of view, the Mandan engaged in a marketing campaign to get the outfitting contract with Lewis and Clark that winter. The Mandan said “why don’t you put your fort here where we can supply you easily?” Sheheke-shote‘s famous, “if we eat you Shall eat, if we Starve you must Starve also,” is as much an economic pronouncement as a gesture of Mandan hospitality. The Hidatsa were somewhat resentful that the Mandan had trumped them in their economic negotiations with the newcomers. It is clear that the Mandan were determined to win the trade contract to supply corn and other produce in exchange for whatever was in those boats. Lewis and Clark then called their compound Fort Mandan because of its proximity to the two Mandan, not the three Hidatsa, villages. If they had found a better fort site—and they were looking for one, they swept the river for twenty miles—they might have built Fort Hidatsa not Fort Mandan. That small geographic decision might have changed the future of the Northern Plains, because the Hidatsa remained skeptical about Lewis and Clark, thwarted their diplomatic initiatives, and continued to wage war on their western enemies, principally the Shoshone. The Hidatsa were much more powerful than the Mandan, and they mattered more on the contested plains west of the five villages. The Hidatsa never really came around; the Mandan did.

From a strategic point of view, Lewis and Clark ought to have spent more time working on the Hidatsa who were actually a more aggressive tribe who traveled more, who had more power, and who were the link with the Canadians. When the Canadians came down to the Knife River villages from the Winnipeg area they had to go through the Hidatsa world to get to the Mandan. And the Hidatsa made sure that they didn’t go around, that whatever trade occurred was mediated by way of the Hidatsa world.

Here’s what happened on November 18th. The leader of the larger of the two Mandan villages was a man named Black Cat, Posecopsahe. We don’t really know whether he was the grand chief of the Mandan or not. Such terms don’t really apply well to native cultures, but Lewis and Clark regarded him as the principal chief of the Mandan world. Posecopsahe visited Fort Mandan, which was still under construction. Lewis was not keeping a journal during this period. Here’s what Clark wrote. It’s just fascinating. “Cold morning. Some wind. The Black Cat chief of the Mandans came to see us. He made great inquiries respecting our fashions.” Now fashion doesn’t mean clothing necessarily, it means culture style or customs. “He also stated the situation of their nation. He mentioned that a council had been held the day before, and it was thought advisable to put up with the recent insults of the Assiniboines and the Cristanos, until they were convinced that what had been told them by us was true.”

Lewis and Clark were essentially saying, “You don’t have to put up with the insults of the Cree or the Assiniboine any longer because America’s here and we’re going to make things safe for you. Break your ties with them.” At the time of the expedition’s visit, the Mandan had trade ties with the Assiniboine and the Cree, tribes that were physically located between the earthlodge villages and the trade forts on the Assiniboine River, but they were bullied by these nations. The Mandan put up with the abuse because the existing trade network, however unpleasant, nevertheless delivered kettles, and blankets, and knives. Lewis and Clark were saying, “Why should you put up with these insults now that we can supply you, not from Winnipeg, but from St. Louis? So just cut your ties with these bad Indians, and throw your lot with us.” Black Cat replies, “Well, we had a council, and we’ve decided it’s advisable to put up with the recent insults of the Assiniboines and the Cristanos until we are convinced that what has promised us by you true.” Well, just what had Lewis and Clark promised?

They said if you break those ties and agree to an exclusive trade contract with us, we’ll supply you all the things you need. Black Cat continues: “Well, Mr. Evans deceived us, and you might also.” In other words, the last guy who came from St Louis and talked this way—Welshman John Evans traveling under a Spanish passport in 1794—had said much the same thing. He said, “We’ll be back. The Spanish trade network from St. Louis will supply the Mandan, not the British” yet he had left and never come back. And that, said Black Cat to William Clark, was ten years ago. In other words, “How do we know you’re ever coming back? We’d better keep this imperfect trade situation going with the Canadians through the intermediary tribes because the last guy who made big promises disappeared and nobody came in his wake.” He promised to return, Evans did, and to furnish the village tribes with guns and ammunition, and he didn’t. Here’s Clark’s response to Black Cat’s challenge: “We advise them to remain at peace. And that they may depend on getting supplies through the channel of the Missouri from St Louis,” but it required time to put the trade in operation. I wonder how much time Clark thought that was going to take. It didn’t really happen until 1820. So from 1804 until 1820, at a time when lifetime expectancy in the Hidatsa-Mandan world was about thirty years, the Americans disappeared, just as Black Cat predicted, and didn’t come back.

So who’s right here? Black Cat was a very shrewd leader. He was thinking, “I have to protect our access to industrial goods, and all this talk . . . I want to see the legacy of this talk, ’cause talk is cheap’.” This episode is just really fascinating, I think.

Two Views of Warfare

Well here’s one more, and then I’ll turn to those metaphors. This is on the return journey in 1806. They left Fort Mandan on April 7th, 1805; they’ve been gone now for more than a year. They returned on August 14th 1806. Lewis is not writing now because he has been recently shot in the buttocks, and he actually says in his journal “that’s it for me—I’m not writing any more. I’m done now.” So here’s Clark:

“Set out at Sunrise and proceeded on. When we were opposite the Minitares Grand Village we Saw a number of the Nativs viewing [us]. We directed the Blunderbuses fired Several times, Soon after we Came too at a Croud of the nativs on the bank opposite the Village of the Shoe Indians . . . at which place I saw the principal Chief of the Little Village of the Menitarre & the principal Chief of the Mah-har-has. those people were extreamly pleased to See us. the Chief of the little Village of the Menetarias cried most imoderately, I enquired the Cause and was informed it was for the loss of his Son who had been killed latterly by the Blackfoot Indians. after a delay of a fiew minits I proceeded on.”

Well here’s what’s interesting about this. First of all, Clark perceives that the Hidatsa are delighted to see them—which may actually be true. Perhaps the Hidatsa were just surprised that the uncouth strangers had been able to survive the immense journey to the Pacific coast and back. But Clark goes on to say that this chief cried because his son had been killed. The back-story of this episode is that the Hidatsa leadership came to Lewis and Clark in the spring of 1805 at Fort Mandan and said, “every year we go out and raid the Blackfeet and the Shoshone—can we conduct our annual raid, according to your diplomatic instructions? Do you think it’s alright?” And Lewis and Clark said, “No, you mustn’t ever do that. You must live in peace from now on. No more raids. We’re insisting, no more raids.” At the time of this exchange, the captains claimed that the Hidatsa reluctantly agreed to abide by their prohibition. Well, as soon as Lewis and Clark left, the usual annual Hidatsa raid took off for western Montana. Lewis and Clark like to think that they’re great, powerful, paternalistic representatives of the Great Father, whose every word will help to guide Indians into a more civilized and peaceful way of life. But the evidence suggests that the Indians they met tended to listen to them with a kind of Seinfeld irreverence: yadda, yadda, yadda. Or, to put it less cynically, what Lewis and Clark were actually saying was, “No more war. You must live in peace, and if you live in peace we’ll guarantee the peace under the security umbrella of the United States government.” But what the native peoples tended to actually hear was, “Whatever the immediate raid you were planning for, say, next Tuesday, don’t do that.” The Indians heard a kind of very localized prohibition. Apparently they thought, “Well, okay, we’ll cancel the next raid.” But they didn’t think, “We’ll cancel raids in perpetuity.” And yet as soon as Lewis and Clark were gone they sort of say, “Well, should we really cancel the next raid? No. The next raid is on!” So, there’s this wonderful kind of mismatch between Lewis and Clark’s pompous certainty that they’re reshuffling the West, and the native view that, “well, you don’t want to be impolite to them. Maybe we comply a little, for right now . . . but why should we change our lifeway?”

There’s a famous moment in North Dakota when a young Hidatsa comes to Lewis and Clark and says, “if we did what you say, how would we get women? Because women only want us if we distinguish ourselves in raids.” So okay, if you remove the way that men impress women in this culture, now what? And then they say, “If we did what you demand, how would we get chiefs, because that’s also how we determine who belongs to the leadership class.” Essentially the Indians are saying, “You know, you’re not just talking about war here, you’re talking about deconstructing the very social dynamics of our culture. What do you have in mind as a substitute social structure and merit system if we follow your advice?” And Lewis and Clark are—we don’t have to blame them—absolutely clueless about what that social revolution would actually mean.

Lewis and Clark see war as Napoleon did, and the native peoples they meet tend to see war as a very, very violent rugby match. For native peoples it’s not fixed battle between big armies of massed troops, it’s skirmishing of small clusters of people. You can never talk about war as a kind of recreation, but there’s a certain element of Indian war on the Northern Plains of this period that the word “war” essentially distorts. Indian war is really something a little bit different. Lewis and Clark can’t really understand that. And in fact, they make a famous mistake when there’s a skirmish between the Sioux and the Mandan in the winter, and there’s a horrible snowstorm, and the Mandan shout across the river that they have this important news, and tell Lewis and Clark that the dastardly Sioux have attacked them. As soon as he hears the news, Clark puts together a large contingent of soldiers and they cross the frozen river over to the Mandan village and say, “alright, let’s go chastise those Sioux,” and the Mandan say, “well, aren’t you blowing this a little out of proportion? It’s a snowstorm, and there’s no bringing back the dead. We’ll wait until spring, and we’ll go down and kill a few of them in retaliation. If you want to come with us then you can help us kill a few of them, but we don’t want to fight a war in a blizzard.” Clark is kind of upset. He’s upset because he’s embarrassed. He’s done this bold thing; he made the big show on behalf of the Great Father, and now the Mandan are rejecting the very security umbrella he has been touting for the last few weeks. So to save face he marches his men around for awhile, just to give them something to justify all of that huff and puff. But the snow is deep and the wind is raw and even Clark soon decides that retaliation can wait until better weather on the northern plains.

Six Metaphors for the Legacy

When I was thinking about this symposium, I was thinking about an essay that I’ve been wanting to write called “Six Similes in Search of an Epic.” In the Homeric world there are all these great similes which are the heart of Homer’s achievement. Virgil dutifully tried to recapitulate that, and Milton, and every other epic writer. The American West doesn’t really have an epic, but there are some great moments and incidents that would lend themselves to an American epic. My favorite of all of them is from the Custer debacle at the Little Big Horn. There’s an account of the battle from an Indian point of view by Wooden Leg. He was asked how long did it take to wipe out Custer and all of his troops? He was silent for a minute, and then he said, “Well, about as long as it takes to eat a snack.” That’s just such a marvelous moment, because it deflates the heroism of Custer and the Indian wars. We think Custer! the boy general, hero of the Civil War, the daring dawn raider of Indian villages, with his Homerically long hair flying behind him as he leads his troops into battle. And yet Wooden Leg’s view was, “well, you know, it required about as long as it takes to eat lunch to go kill them all.” The simile creates a massive imbalance between the cultural attachment we have created for this story and the nonchalance of Wooden Leg. It is even more powerful because it belongs to what is known as primary rather than secondary (literary, self- conscious) epic. In other words, we are dealing with the oral traditions that come straight out of the episode, not a carefully crafted re-creation benefiting from reflection and historical synthesis.

I would like to propose a few metaphors for the Lewis and Clark story, not in any definitive way, but merely to help us all think about the legacy of the expedition.

One—A Pebble in a Pond

When a pebble falls in a pond, if it’s a calm pond, it creates dramatic concentric circles that begin to dissipate as they move farther and farther from the point of origin. If the water is unruffled, those concentric circles will find their way miles to the end of the lake. You’ve all seen Hallmark Card photographs of this. According to this metaphor, Lewis and Clark arrive, it’s a dramatic moment in the history of the Shoshone or Walla Walla or Oto, and then they depart as quickly as they came. The concentric circles of the expedition’s influence and legacy play themselves out for a period of time, more if the tribe’s world is unruffled when the newcomers arrive, less so if it is ruffled by more pressing concerns, but the influence does not continue forever. There was calm. Then an event occurred in the center of the tribe’s pond, as if dropped from the sky, and then the impact played itself out in an entirely natural way over a limited period of time. That’s one possible metaphor for Lewis and Clark.

Two—The Fatal Moment

It comes from Alan Morehead, who has written extensively about “first encounters” between more industrial and less industrial peoples, or more advanced and less advanced peoples, depending on one’s perspective. It’s a marvelous metaphor. His metaphor is not from the Great Plains, it’s actually from the South Pacific. Morehead spoke of, “that fatal moment when a social capsule was broken open.” First contact with the Shoshone, first contact with Tahitians, first contact with people of the Solomon Islands. Moorhead is describing the moment when representatives of a very different culture suddenly appear, and their appearance cracks the indigenous culture, and that culture is cracked forever. Something innocent, or at least intact, is lost forever. The indigenous culture is now “dis-covered,” and the fissure has the same effect that a crack in an egg creates. The crack can be sealed, imperfectly, but the crack is now a fact of life and nothing is ever quite the same after that crack.

Three—Paradise Lost

The third one has had a lot of play during the Bicentennial and I think it’s pretty unfair, actually. The third metaphor is the metaphor of a tsunami. You heard a lot of this early on in the Bicentennial, that before Lewis and Clark, the West was the Garden of Eden, environmentally and culturally, and then Lewis and Clark came. The expedition represents a kind of disastrous wave that shattered and engulfed the American West. The Indian cultures of the West were thriving when Lewis and Clark arrived, and they were perfectly adapted to their environment. They had their own science, advanced social structures, technologies that not only resonated with their cultural norms, but that embodied cultural restraining energies that made Indian cultures sustainable. At the first national signature event, at Monticello, there were a number of panels that came back to this theme again and again. Everything was fine until Jefferson sent Lewis and Clark up the Missouri.

Needless to say, I don’t think that can be true given what we’ve already talked about in terms of native attitudes towards Lewis and Clark, native sophistication about trade and sovereignty issues, native capacities for cultural adaptation and the usual give and take of human nature, and native good sense about the transience of Lewis and Clark. It seems clear that the tsunami metaphor satisfies a national cultural need for both Indians and non-Indians. We all tend to aggrandize the pre-contact world and we degrade the post-contact reality. The Eden myth—though it clearly has some basis in fact, at least in terms of relative impacts on the surrounding environment—serves in a double capacity for non-Indians. Primarily it allows us to process or imperial guilt for the forceful Europeanization of North America, but it also in a sly way makes us feel good about the potency of the culture we currently choose to decry. In other words, tsunami has a clandestine capacity to make white people feel triumphant, even if we like to distance ourselves from that very spirit. And for Indians, the tsunami metaphor not only does the crucial work of envisioning a prelapsarian world of innocence, a Native American golden age, but it provides a neat apologia for whatever is wrong in Indian country today. It’s not Indians who have created the intractable problems of Indian America; they are resolutely doing what they can to survive the legacy of conquest.

For compelling enough reasons, however suspect they are historically, the tsunami metaphor serves both cultures pretty well at the present time. We posit a virgin land and an innocent people, and then we reckon with the power-hungry, aggressive new guys on the block who shattered that paradigm. It turns out that the lost innocence of Indians is our lost innocence too. “In the beginning,” wrote John Locke, “all the world was America.” It’s a form of the old noble savage myth, and it’s a highly unfair one, but it has a lot of potency. In the Lewis and Clark world, there’s a lot of nostalgia. And if you’ve watched the Bicentennial unfold, Indians—sometimes by themselves but more often by invitation—have frequently enough “suited up” as creatures locked in time. It’s an odd and somewhat troubling phenomenon. One of the people I most respect is Amy Mossett who is a Mandan woman. We go to Rotary Clubs together and we have coffee together and we’re on planes together, both dressed in 21st century American clothing. Yet when there’s a Lewis and Clark event she often suits up in a buckskin dress and she looks perfectly gorgeous and everyone wants to get close to her. They would be sorry if she showed up in a business suit. Well, that’s so uncanny if you think about it, that Indians in the Bicentennial are encouraged to suit up as creatures out of another time. She doesn’t go to the grocery store in her buckskins. We all get why it happens, and why it represents a continuing linkage to the authentic pre-industrial culture, and we know why it’s important, but it’s also troubling in a way that is difficult to articulate. It teases out a really deep problem in white-Indian relations. Amy Mossett talks about this and she increasingly chooses not to make appearances in her buckskins, but in what might be called “western wear,” what, if a non-Indian wore it, would be called an “Indianized” form of western dress.

Four—Seeds of Change

According to this trope, Lewis and Clark planted a seed—let’s call it a seed of change—and it didn’t sprout immediately. Without always knowing what they were doing, the explorers planted a few seeds that sprouted over time. Some of them flourished and changed the world that the expedition traveled through and some of the seeds didn’t flourish. Lewis and Clark as cultural sowers seems a little better metaphor than a tsunami to me because if Lewis and Clark had never come at all—let’s just say there had never been Jefferson or a Lewis or a Clark—would Portland be the same or different? Would Bismarck be the same or different? It’s hard to think that there would be no Bismarck if there were no Meriwether Lewis. Or no strip mining, or no interstate highways or no Burger King restaurants.

It’s a little bit like the Homeric Question. In Homer studies there’s an endless debate about whether Homer is actually the author of the Homeric poems. We know we have the Iliad and the Odyssey and they’re said to be by an epic poet named Homer, but increasingly it’s pretty clear that the composition of the two great epics is more complicated than we used to think. The most famous statement about this was made by an English classicist. As he put it, “the Iliad and the Odyssey were written by Homer or by another chap by the same name.” In other words, if Lewis and Clark hadn’t come at all, it would have been Peter and Charles, or Hancock and Dickson, or Evans and Novak, but whoever it was—particularly if it was an Anglo-American party—would have planted much the same seed. To give the two actual individuals Lewis and Clark (or the men they led, or even represented) so much agency of legacy is a form of historical fallacy. Yes, of course, there’s a direct line of legacy, and they were quite clearly running Jeffersonian software. Jefferson is the genius behind the expedition. That matters. It’s not Madison, it’s not Adams, and it’s not James Wilkinson, and it’s not Zebulon Pike. It’s Jefferson’s brainchild.

What if they had never come? How would things have unfolded differently? What are other possibilities for the unfolding of the American West? How important are Lewis and Clark? It’s possible that they’re merely representative, rather than determinative, if that makes any sense. In other words, there was going to be a Europeanization of North America one way or the other, and Lewis and Clark are not much more than early harbingers of that Europeanization. Absent Lewis and Clark, that process would have unfolded more or less as it did. It’s an interesting question—if Jefferson had been John Marshall instead, or if John Marshall had been the third president of the United States, with his more generous view of native sovereignty, who knows?

Five—The Hand in the Basin

This one comes from my favorite writer, John Donne. According to this metaphor Lewis and Clark essentially had no impact. They came, they went, maybe they sullied things a little but the West sealed up the minute they walked out of the picture. It wasn’t cracked—it wasn’t planted with anything, it wasn’t devastated by their power, it just opened and then it closed. Here’s the gorgeous passage from a 1622 sermon that Donne preached at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. I’ll just pick it up in midstream. He says, What if God had left thee a Papist, a Catholic:

as though that God hath done so much more, in breeding thee in his true Church, had done all this for nothing, thou passest thorough this world, like a flash, like a lightning, whose beginning or end no body knows, like an Ignis Fatuus in the aire, which does not onely not give light for any use, but not so much as portend or signifie any thing; and thou passest out of this world, as thy hand passes out of a basin of water, which may be somewhat the fouler for thy washing in it, but retaines no other impression of thy having been there.

Isn’t that beautiful? You pass out of this world, “as thy hand passes out of a basin of water, which may be somewhat the fouler for thy washing in it, but retaines no other impression of thy having been there.” That’s gorgeous—and of course from a Christian point of view, terribly unsettling. John Donne was a great poetic genius and his 17th century sermon may help to illuminate the legacy of Lewis and Clark.

I don’t think Donne’s metaphor fully applies, either. I think Lewis and Clark’s impact was greater than that, but it’s worth putting the basin trope in the mix of possibilities. Certainly if Lewis and Clark had not been harbingers, if they had visited Indian Country in the same sense that a handful of American astronauts visited the Moon in the 1960s and 70s, a brief proud presence and then a complete withdrawal without the mass of humanity following in their wake, Donne’s view might be correct. But they were harbingers of a fur rush that made it impossible for the basin to shrug them off.

Six—The Bug in the Board

Finally, I want to modify the seed metaphor, as refashioned by Henry David Thoreau. Many of you know this famous late passage from Walden, about how our lives bear fruits in ways we can’t anticipate and that there may be long periods of dormancy before those fruits are borne. This is quintessential Thoreau:

Every one knows the story which has gone the rounds of New England, of a strong and beautiful bug which came out of the dry leaf of an old table of apple-tree wood, which had stood in a farmer’s kitchen for sixty years, first in Connecticut, and afterward in Massachusetts—from an egg deposited in the living tree many years earlier still, as appeared by counting the annual layers beyond it; which was heard gnawing out for several weeks, hatched perchance by the heat of an urn. Who does not feel his faith in a resurrection and immortality strengthened by hearing of this? Who knows what beautiful and winged life, whose egg has been buried for ages under many concentric layers of woodenness in the dead dry life of society, deposited at first in the alburnum of the green and living tree, which has been gradually converted into the semblance of its well-seasoned tomb—heard perchance gnawing out now for years by the astonished family of man, as they sat round the festive board—may unexpectedly come forth from amidst society’s most trivial and handselled furniture, to enjoy its perfect summer life at last!

So maybe the Lewis and Clark story embodies that metaphor; there’s a hidden bug at the center of it. Wouldn’t it be ironic if a bug metaphor governs this story and all this time we’ve been imprecisely talking about buffalo and grizzly bears, the barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) and bull boats, Dr. Rush’s thunderclappers and guns, how many elk they killed and how many pounds of meat they ate per day, and where they camped on such and such a night, and whether the lead they used for bullets was from a mine in Missouri or Kentucky? All these are interesting questions. Unfortunately, they have tended to dominate the Bicentennial much more than is sensible. I think the great Thoreau would say, maybe the bug, the true seed of this story has yet to surface. At times the Bicentennial has come close. I think there have been some sublime moments in the Bicentennial and some of them have been here at Lewis and Clark College and in the splendid public radio series we produced. Mostly, though, I am struck at the end of this five-year commemoration by the level of superficial discourse it has generated and by how little, on the whole, the American community, including the presenter community, has searched for the miraculous insights that have been fighting to get to the surface.

Concluding Thoughts

I think that Thoreau’s metaphor is a really very promising. I think that it embodies what Thomas Slaughter urged in his interesting, but imperfect, book on Lewis and Clark, Exploring Lewis and Clark, and what David Nicandri has been advocating in his fresh analysis of Lewis and Clark, and it’s what James Ronda and John Logan Allen have been insisting upon. In different ways, these humanities scholars have all be saying the same thing: now that we have a definitive thirteen volume national edition of Lewis and Clark, edited by Gary Moulton of the University of Nebraska, and the text has been established for our time, and we have before us all the journal voices, all the ones that are extant, and new letters have been found in Louisville, and we’re ready, for the first time, to listen respectfully to the wide range of oral memories that Native Americans have been rescuing from oblivion, we need to explore Lewis and Clark with fresh critical eyes. We’re not at the final dispensation of the text, as the Bicentennial ends, but we’re a lot closer than we’ve ever been before. At the very least, now we have a standard text that can be relied upon. Now we need that device from the Men in Black movies—we need to take that pen-like, laser-like device, and click it, and blank out the Lewis and Clark sectors of all of our brains so that we no longer have any notion of who Lewis and Clark were. And once we have become Jefferson’s and John Locke’s tabulae rasae, we need to explore the journals with fresh souls as if we were reading Hamlet for the first time, as if we were reading Great Expectations or Anna Karenina or Thoreau or John Donne for the first time.

If we could do that, if we could erase our myth concepts of Lewis and Clark and actually look at the text as if it had just been unearthed from a trunk in an attic in St. Paul or Louisville, and let it tell us what it needs to tell us, coupled with native oral traditions—which are increasingly central to the understanding of this story—and a deep broad environmental awareness, and a whole range of bio-regional understandings that were unthinkable in the time of Donald Jackson—if we could do that and dispossess ourselves of the things that trip us up, that Thoreauvian bug might be able to crawl out of the table of Lewis and Clark, and it might reawaken something really extraordinary in our national consciousness.