A bald eagle gains airspeed and altitude as it takes off from the ice on the Clark Fork (Clark’s) River in downtown Missoula, Montana, lugging a freshly-killed goldeneye, a species of duck known for its ability to dive deep and stay under water for as long as two minutes.[1]The common goldeneye duck (Bucephala clangula) is native to coniferous forests in North America and Eurasia. Its generic name (bu-SEFF-ah-lah) comes from a Greek word meaning ox- or buffalo-headed, … Continue reading Bald eagles often hunt in pairs, and this one’s mate had just taken off with a similar meal of its own. Apparently no one witnessed these two kills except the photographer, but the 19th-century naturalist and illustrator John James Audubon (1785-1851) once observed a pair take turns swooping down on their prey to force it under water again and again until it was exhausted, and to catch its breath was forced into shallow water where the eagles could finally capture it.[2]Quoted in Alexander Wilson and Charles Lucian Bonaparte, American Ornithology; or the Natural History of the Birds of the United States, ed. Robert Jameson, 4 Vols, (Edinburgh: Constable and Co., … Continue reading

Figure 2

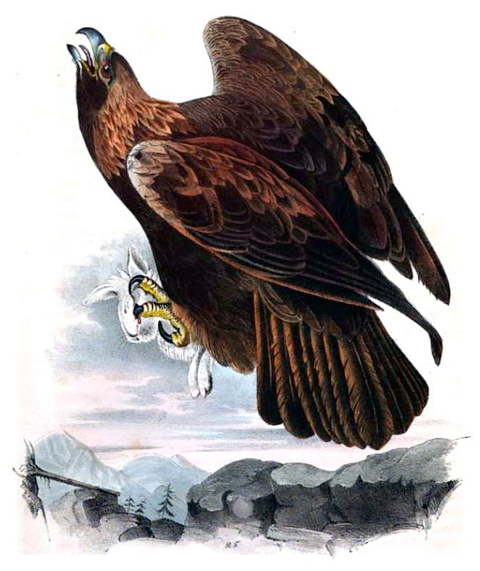

Catesby’s “Bald Eagle”

Aquila Capite Albo

Courtesy University of Wisconsin Digital Collections Center.

The English naturalist Mark Catesby (1683-1745) spent seven years in Virginia beginning in 1712. Catesby’s own hand-tinted engraving of the bird he preferred to call Aquila Capite Albo, or “eagle with white head” (although he grudgingly labeled it with the common name it had already acquired) appeared in his Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, which was published privately in London between 1741 and 1743. Catesby confirmed that this species “always make their Nests near the sea, or great rivers, and usually on old, dead Pine or Cypress-trees, continuing to build annually on the same tree.” The awkward pose, simultaneously presenting a side view of the body and a top view of the outspread wings, was characteristic of the style of many drawings of birds prior to Audubon’s work (Figure 4), because with a dead bird as a model, it was easier to draw than a more realistic view.

The sharp eyes set deep beneath beetled brows, combined with the hooked beak and the menacingly lowered head at the wings’ upstroke, lend this Haliaeetus leucocephalus a distinctly pugnacious appearance. The bald eagle steals much of its nourishment from turkey vultures and other scavengers, and especially from ospreys, which Meriwether Lewis and William Clark knew as “fishing hawks.”[3]The osprey (Pandion haliaetus) is somewhat smaller than either of these eagles.The generic name comes from Pandion, the mythical King of Athens, whose daughters Philomena and Procne who were turned … Continue reading The specimen pictured above, true to its long-established reputation, carries in its left talon part of a fish, which photographer Steve Sherman had just watched it snatch from an osprey.

Two Species

En route to the Pacific Ocean, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark saw both species of eagles that are native to North America: the black-and-white one called the bald eagle, and the brown-and-gold one commonly known as the golden eagle, but which the explorers knew as the grey eagle. The bald eagle, which is among the largest raptors[4]Neither Lewis nor Clark would have known the term raptor, which is derived from a Latin verb rapio, meaning “to snatch, grab, carry off.” Early in the second quarter of the nineteenth … Continue reading found worldwide in the northern hemisphere, was already well known to naturalists in Europe and America. Moreover, it was so conspicuous and numerous along the eastern seacoast, as well as on inland rivers, that it seemed to a majority of members of the Continental Congress in 1782 to be a logical choice for a central image in the Great Seal of the United States.

Carl Linnæus had listed the bald eagle in a 1766 revision of the tenth edition (1758) of his Systema Naturae, basing his description on an engraving in Catesby’s Natural History (Figure 1). He placed it in the same genus as the falcon, renaming it Falco leucocephalus, or white-headed falcon, his color description being more literal than “bald.” He also named the other North American species Falco fulvus, or golden falcon.[5]Falco is another Latin word for hawk. His taxonomies were revised a number of times during the next three-quarters of a century, as more observations were made and more details recorded.

“Calumet” Eagle

At Fort Clatsop on 14 and 15 March 1806, however, Lewis and Clark summarized their knowledge of an eagle that appeared to them to belong to a third species, which they had learned from their French-Canadian engagés, and concluded from Indian information, to call the “calumet” eagle. Nicholas Biddle repeated their account of it almost verbatim in his paraphrase of their journals.[6]History of the Expedition under the command of Captains Lewis and Clarke to the sources of the Missouri, thence across the Rcky Mountains and down the river Columbia to the Pacific Ocean, performed … Continue reading

The calamut [calumet] eagle sometimes inhabits this [the west] side of the Rocky mountains. This information Captain Lewis derived from the natives, in whose possession he had seen the plumage. These are of the same species of those of the Missouri, and are the most beautiful of all the family of eagles in America. The colors are black and white, and beautifully variegated.

The tail-feathers, so highly prized by the natives, are composed of twelve broad feathers of unequal lengths, which are white, except within two inches of their extremities, where they immediately change to a jetty black; the wings have each a large circular white spot in the middle, which is only visible when they are extended; the body is variously marked with black and white. In form they resemble the bald eagle, but they are rather smaller, and fly with much more rapidity.

This bird is feared by all his carnivorous competitors, which, on his approach, leave the carcass instantly, on which they had been feeding. The female breeds in the most inaccessible parts of the mountains, where she makes her summer residence, and descends to the plains only in the fall and winter seasons. The natives are at this season on the watch; and so highly is this plumage prized by the Mandans, Minnetarees, and Ricaras, that the tail-feathers of two of these eagles will be purchased by the exchange of a good horse or gun, and such accouterments.

Among the Great and Little Osages, and those nations inhabiting the countries where the bird is more rarely seen, the price is even double that above mentioned. With these feathers the natives decorate the stems of their sacred pipes of calumets, whence the name of the calumet eagle is derived.[7]Calumet, from a French word for reed, was applied by French explorers and traders to the sacred Indian pipe of peace and friendship, which consisted of a clay or stone bowl and a long hollow stem … Continue reading The Ricaras have domesticated this bird in many instances, for the purpose of obtaining its plumage. The natives on every part of the continent who can procure the feathers, attach them to their own hair and the manes and tails of their favorite horses, by way of ornament. They also decorate their war-caps or bonnets with those feathers.[8]For an example, see the photographic portrait of the Mandan chief, Struck by the Ree, in The Expedition’s Flags.

The captains’ mistake is excusable. It was an inevitable consequence of the fact that on this subject early ornithologists were still sorting out fact from fancy and fable, and learning by consensus when to believe their eyes, and when to look again. The confusion prevailed until 1828, when Alexander Wilson declared that most ornithologists were finally of the opinion that the “calumet” or “ring-tailed” eagle was really the golden eagle at a certain stage of growth.[9]American Ornithology; or The Natural History of the Birds of the United States (New York: Collins & Co., 1828), 65.

Hawk Family

Both the bald and golden eagle are now classed among the hawk family, or Accipitridae (ak-si-PIT-rid-eye; Latin for hawk or bird of prey), rather than the family Falconidae (fal-KON-id-eye). Furthermore, it is now understood that they belong to two separate genera that are only remotely related. The bald eagle represents the genus Haliæetus (hal-ih-eye-EE-tus), from the Greek name for “sea eagle.” The specific epithet, leucocephalus (lew-koh-SEFF-ah-lus), is a blend of the Greek words leukos, white, and kephale, head. It is native to most of North America from eastern Canada to the Pacific Coast, including the tip of the Aleutians, and southward into northern Mexico. Primarily fish eaters, they nest high in riverside trees and on the shores of lakes and oceans. At the mouth of the Yellowstone in late April 1805, Meriwether Lewis wrote: “The bald Eagle are more abundant here than I ever observed them in any part of the country.” Evidently the habitat was ideal in terms of their favorite food.

The golden eagle belongs to the genus Aquila (AK-wih-la)—the Latin word for eagle. The specific epithet chrysaetos (kris-AY-ee-tos) is a combination of the Greek words chrysos, golden, and aetos, eagle. The name golden comes from the patch of brownish-yellow feathers on the nape of an adult’s neck (Figure 4). The species, is distributed globally throughout the northern hemisphere, principally in mountainous terrain. In North America it thrives west of the 100th parallel, from central Mexico to the northern tip of Alaska. It is rarely seen east of the Platte River, which largely accounts for the confusion over the “calumet” eagle in Lewis and Clark’s time.[10]Today’s replica of Fort Mandan, a mile west of Washburn, North Dakota, near the supposed site of the original, is at 101.05° West, 47° 17′ North. Lewis and Clark saw bald eagles above … Continue reading

Bald Eagle

Ornithologist Alexander Wilson, a friend of Lewis’s, was skeptical of the then-current folk wisdom that the white-headed eagle could live to “a great age, sixty, eighty, and as some assert, one hundred years.” Those estimates seemed remarkable, he wrote, “when we consider the seeming intemporate habits” of a bird that feeds on carrion.[11]Alexander Wilson, American Ornithology; or The Natural History of the Birds of the United States (New York: Collins & Co., 1828), 56. Twentieth-century techniques for tracking eagles, such as the band seen on the right leg of the specimen in Figure 3, have provided more reliable information. Captive bald eagles have been known to live as long as 36 years, but the maximum longevity among Alaskan wild eagles in a 1997 study was 28 years.[12]The Birds of North America Online, http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/, accessed 20 November 2008.

An adult bald eagle is between 34 and 43 inches long, with a wingspread of from 6 to 71/2 feet. Its head and tail are snow-white; its body is brownish black, and its bill, eyes, and feet area luminous yellow. A male may weigh 8 to 9 pounds, a female as much as 14 pounds. The bald eagle pictured above is easily recognizable as mature specimen (more than four years old), judging from its coloration alone. A juvenile (up to one year old) would have a dark brown head, tail and body, which can easily lead to a misidentification of a young baldy as a mature golden. That may have been the basis of some early taxonomists’ confusion, including that of Lewis and Clark.

The bald eagle has also been called the American eagle, black eagle (see Black Eagle Falls of the Missouri), fishing eagle, Washington eagle (Audubon’s honorific name for what he once thought was a new species), white-headed eagle, and white-headed sea eagle.

Golden Eagle

On 11 July 1805 Lewis wrote, “I saw several very large grey Eagles today,” in the vicinity of the portage camp above the Great Falls of the Missouri. “They are a half as large again as the common bald Eagle of this country. I do not think the bald Eagle here qu[i]te so large as those of the U’ States; the grey Eagle is infinitely larger and is no doubt a distinct species.” He was partly right. It is a distinct species from the bald eagle, but on average, it is slightly smaller, ranging between 33 and 38 inches in length, but with a wingspan about the same as the bald eagle’s. In mass, the female golden averages a little more than three pounds heavier than the male. The greatest longevity among wild goldens studied in 1997 was 23 years 10 months.[13]Ibid.

Subadult goldens (less than five years of age) are “ringtailed,” having white tailfeathers with black tips–the feathers that were deemed especially valuable by Indian men. On 21 August 1805, as he studied the character and culture of the Lemhi Shoshones, Lewis observed that their men were “fond of the feathers of the tail of the beautifull eagle or callumet bird [that is, the golden eagle] with which they ornament their own hair and the tails and mains [manes] of their horses.” Subadults also have a large white spot on the underside of each wing. Their legs, unlike the bare legs of the bald eagle, are “booted” or feathered all the way down to the toes. At various stages in their lives, goldens may range from light brown to dark grey-black, overall.

Flight Characteristics

One of the golden eagle’s most remarkable traits is its ability to soar to great heights and distances on rising thermals–which may be one source of Indians’ reverence toward it as the “sun bird.”[14]Thomas E. Mails, The Mystic Warriors of the Plains (New York: Doubleday, 1972), 302. William Swainson (1789-1855), as yet unfamliliar, no doubt, with the existence of thermal updrafts over land, nevertheless accurately observed that,

When looking for its prey, it sails in large circles, with its tail spread out, but with little motion of its wings; and it often soars aloft in a spiral manner, its gyrations becoming gradually less and less perceptible, until it dwindles to a mere speck, and is at length entirely lost to the view.[15]John Richardson, William Swainson, et al, Fauna Boreali-americana, Or, The Zoology of the Northern Parts of British America (London: J. Murray, 1829-37), 12.

Equally impressive is the speed of its flight. It can glide at up to 115 mph, and an unverified estimate claims it can “stoop” (i.e., swoop)[16]Coincidentally, the real name of Tobe, or “Toby,” the Shoshone man who guided the Corps of Discovery across the Bitterroot Mountains, was Pi-kee queen-ah, or “swooping eagle.” … Continue reading almost vertically at more than 150 mph. Numbers aside, with simple bold imagery the English poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892) captured these two attributes of both species of eagles in a mere six lines:

He clasps the crag with crooked hands;

Close to the sun in lonely lands,

Ring’d with the azure world, he stands.

The wrinkled sea beneath him crawls;

He watches from his mountain walls,

And like a thunderbolt he falls.[17]“The Eagle: A Fragment ” in The Poetical Works of Alfred Tennyson, 2 vols. (Boston: Ticknor, Reed, and Fields, 1861), 1:165. EBook (Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Library, … Continue reading

In olden times the golden eagle was often called the “bird of Jupiter,”[18]In the mythology of Roman civil and religious life it was the bird of Jupiter, the king of the gods, whose earthly emmisary was the Imperium or supreme ruler of the Roman Empire. Perforce it … Continue reading, brown eagle, more recently the jackrabbit eagle (from its discriminating appetite for Lepus townsendii (See Hares and Jackrabbits), mountain eagle, ringtailed eagle, and royal eagle. Lewis and Clark recognized it as the grey eagle. Indians knew a juvenile golden as the war eagle (from the use of its tailfeathers in battle dress), and spotted eagle (for its coloration when in its prime as a source of ceremonial tailfeathers.

Catlin’s Experience

Artist George Catlin recalled that during a trip through the Breaks of the Missouri River with Prince Maximilian of Wied on an April day in 1833:

We whiled away the greater part of this day amongst the wild and ragged cliffs, into which we had entered; and a part of our labours were vainly spent in the pursuit of a war-eagle. This noble bird is the one which the Indians in these regions, value so highly for their tail feathers, which are used as the most valued plumes for decorating the heads and dresses of their warriors. It is a beautiful bird, and, the Indians tell me, conquers all other varieties of eagles in the country; from which circumstance, the Indians respect the bird, and hold it in the highest esteem, and value its quills. . . . This bird has often been called the calumet eagle and war-eagle.[19]George Catlin, North American Indians, ed. Peter Matthiessen (New York: Penguin Books, 1989), 65.

The Indian method of capturing a “war-eagle” was for the hunter to dig a pit large enough to crouch in. He covered the pit with brush and logs, and tied atop it some part of a small animal’s carcass, such as a rabbit’s. When an eagle landed to seize the bait, the hunter deftly reached through the blind, grabbed it by its legs, and either wrung its neck or, if it was a very young specimen, tied it securely to keep it from injuring itself or him, and carried it home to raise until its tailfeathers grew into the right size and colors.[20]These procedures, including the solemn preparatory rituals that were obligatory, is described in detail by a Sioux hunter named Iron Shell, in Royal B. Hassrick, The Sioux (Norman: University of … Continue reading

Captured by Cutnose

Meriwether Lewis, while biding time with the Nez Perces in the spring of 1806, reported (9 June 1806), that Cutnose, one of the four principal chiefs of that Indian nation, had borrowed a horse from him and ridden down the Clearwater a few miles “in quest of some young eagles which he intends raising for the benefit of their feathers; he returned soon after with a pair of young Eagles of the grey kind; they were nearly grown and pretty well feathered.” Lewis left us no clue as to how Cutnose captured the two raptors so quickly.

Decline and Recovery

Before the middle of the nineteenth century the population of bald eagles had already begun to diminish as a result of human expansion westward and the resultant impact on eagle habitat.[21]Audubon noticed the adverse impact of steam navigation on bald eagle populations along the lower Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, and some tributaries, presumably because of the cutting of riverside … Continue reading The golden eagle suffered the same fate by the end of the same century. During the first half of the 20th century the erroneous conviction that eagles preyed on sheep and lambs made them the targets of bounty hunters paid from state subsidies. The shooting and trapping of eagles was finally outlawed in the lower 48 states by authority of the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act of 1940 (16 U.S.C. 668a-d), and the territory of Alaska followed suit in 1953. After World War II, as an unanticipated consequence of the increased use of DDT and Endrin to control agricultural pests, specifically insects, both eagles were again driven to the brink of extinction. In 1980, for example, only 13 successful bald eagle nests could be found in the entire state of Montana.[22]Harold D. Picton and Terry N. Lonner, Montana’s Wildlife Legacy: Decimation to Restoration (Bozeman, Montana: Media Works Publishing, 2008), 239-40. Meanwhile, the use of these insecticides had been prohibited, and in 1978 the bald eagle was added to the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants. By 2006 there were at least 280 successful bald eagle nests in Montana, and the species was delisted in 2007. In 1994, President William J. Clinton issued a Memorandum (59 F.R. 22953) establishing a policy concerning collection and distribution of eagle feathers for religious observances by Native Americans.

Principal Sources

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, The Birds of North America Online http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna.

John K. Terres, The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds. New York: Wings Books, 1991.

Notes

| ↑1 | The common goldeneye duck (Bucephala clangula) is native to coniferous forests in North America and Eurasia. Its generic name (bu-SEFF-ah-lah) comes from a Greek word meaning ox- or buffalo-headed, from its exceptionally large head; the specific epithet (KLANG-yoo-lah) is a Latin reference to the vibrant whistling chime of its wings in flight. A very swift and strong flier, a male goldeneye will weigh, on average, 2½ pounds, the female only a little less. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Quoted in Alexander Wilson and Charles Lucian Bonaparte, American Ornithology; or the Natural History of the Birds of the United States, ed. Robert Jameson, 4 Vols, (Edinburgh: Constable and Co., 1831), 4:270-72. |

| ↑3 | The osprey (Pandion haliaetus) is somewhat smaller than either of these eagles.The generic name comes from Pandion, the mythical King of Athens, whose daughters Philomena and Procne who were turned into a swallow and a nightingale, respectively, by Procne’s husband, Tereus. |

| ↑4 | Neither Lewis nor Clark would have known the term raptor, which is derived from a Latin verb rapio, meaning “to snatch, grab, carry off.” Early in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, ornithologists began using it as a catch-all term for avians otherwise known euphemistically as “birds of prey”—eagles, hawks, buzzards, owls, ospreys, falcons and kites. All are meat-eating birds equipped with talons and beaks that equip them to tear or pierce flesh. The English ornithologist William Swainson (1789-1855) was among the first to refer to them as raptorial. |

| ↑5 | Falco is another Latin word for hawk. |

| ↑6 | History of the Expedition under the command of Captains Lewis and Clarke to the sources of the Missouri, thence across the Rcky Mountains and down the river Columbia to the Pacific Ocean, performed during the years 1804-5-6, [edited by Nicholas Biddle and] prepared for the press by Paul Allen, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: 1814), 2:188. Paragraph breaks added for ease of reading. |

| ↑7 | Calumet, from a French word for reed, was applied by French explorers and traders to the sacred Indian pipe of peace and friendship, which consisted of a clay or stone bowl and a long hollow stem fashioned from the stalk of a common water plant. Historically, various kinds of suitable stone were available regionally, but the stone favored among Plains Indians was an exceptionally soft type of metamorphosed mudstone or argillite, which officially gained the name catlinite following artist George Catlin‘s 1835 visit to an ancient Indian quarry in Minnesota. The stem frequently was decorated with golden eagle feathers. |

| ↑8 | For an example, see the photographic portrait of the Mandan chief, Struck by the Ree, in The Expedition’s Flags. |

| ↑9 | American Ornithology; or The Natural History of the Birds of the United States (New York: Collins & Co., 1828), 65. |

| ↑10 | Today’s replica of Fort Mandan, a mile west of Washburn, North Dakota, near the supposed site of the original, is at 101.05° West, 47° 17′ North. Lewis and Clark saw bald eagles above the mouth of the Kansas River, which today is at 94° 36′ West and 39° North. A degree of longitude between those latitudes ranges between 54 and 47 statute miles. The confluence of the Platte and Missouri Rivers near Omaha, Nebraska, is at about 41° 03′ North Latitude, 95° 52′ West Longitude. |

| ↑11 | Alexander Wilson, American Ornithology; or The Natural History of the Birds of the United States (New York: Collins & Co., 1828), 56. |

| ↑12 | The Birds of North America Online, http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/, accessed 20 November 2008. |

| ↑13 | Ibid. |

| ↑14 | Thomas E. Mails, The Mystic Warriors of the Plains (New York: Doubleday, 1972), 302. |

| ↑15 | John Richardson, William Swainson, et al, Fauna Boreali-americana, Or, The Zoology of the Northern Parts of British America (London: J. Murray, 1829-37), 12. |

| ↑16 | Coincidentally, the real name of Tobe, or “Toby,” the Shoshone man who guided the Corps of Discovery across the Bitterroot Mountains, was Pi-kee queen-ah, or “swooping eagle.” John E. Rees, “The Shoshoni Contribution to Lewis and Clark,” Idaho Yesterdays, 2 (Summer 1958): 11. |

| ↑17 | “The Eagle: A Fragment ” in The Poetical Works of Alfred Tennyson, 2 vols. (Boston: Ticknor, Reed, and Fields, 1861), 1:165. EBook (Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Library, 2005) http://name.umdl.umich.edu/ADH8813.001.001 (accessed 15 January 2009). |

| ↑18 | In the mythology of Roman civil and religious life it was the bird of Jupiter, the king of the gods, whose earthly emmisary was the Imperium or supreme ruler of the Roman Empire. Perforce it symbolized the power of the god’s earthly namesake’s legions, and the Empire’s right to rule the Roman world and manifest that right with righteous wars. |

| ↑19 | George Catlin, North American Indians, ed. Peter Matthiessen (New York: Penguin Books, 1989), 65. |

| ↑20 | These procedures, including the solemn preparatory rituals that were obligatory, is described in detail by a Sioux hunter named Iron Shell, in Royal B. Hassrick, The Sioux (Norman: University of Oklahoma press, 1964) 195-96. |

| ↑21 | Audubon noticed the adverse impact of steam navigation on bald eagle populations along the lower Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, and some tributaries, presumably because of the cutting of riverside trees to fuel the steamboats’ boilers. Constable’s Miscellany of Original and Selected Publications in the Various Departments of Literature, Science, & the Arts, Vol. LXXI, Alexander Wilson and Charles Lucian Bonaparte, ed., The American Ornithology, Vol. IV (Edinburgh: Constable & Co., 1831). Appendix. John James Audubon, The Birds of America, 178. Google Books, American_Ornithology.pdf. |

| ↑22 | Harold D. Picton and Terry N. Lonner, Montana’s Wildlife Legacy: Decimation to Restoration (Bozeman, Montana: Media Works Publishing, 2008), 239-40. |