Enigmatic Engagés

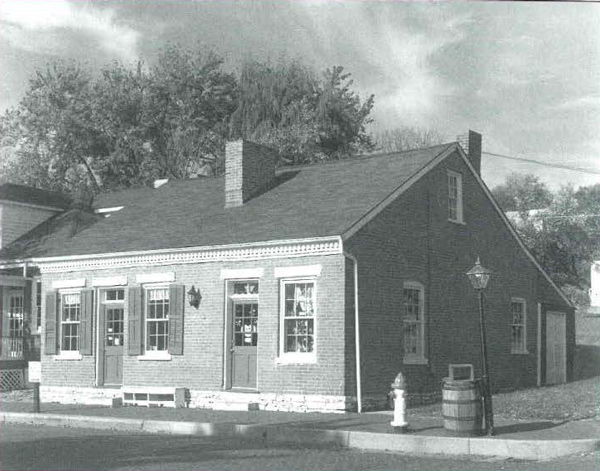

Behind this early 19th-century French-style house stood the original St. Charles Borromeo vertical log church.

On Sunday, 6 May 1804, just a few days remained before the departure of the Corps of Discovery. William Clark and the men at the Wood River campsite enjoyed the fine spring weather. Frequent target practice over the previous winter paid off that day when Corps members beat some visitors to their camp in a shooting match. Across the Mississippi River, Meriwether Lewis endeavored to tie up bureaucratic loose ends in St. Louis. And across the Missouri River, a young man named Charles Pineau, son of a Missouri Indian woman and a French-speaking man, knelt for baptism in the Catholic church of St. Charles.

Later that week, hunter and interpreter George Drouillard arrived at the Wood River camp with seven French-speaking boatmen Charles Pineau quite possibly among them. Soon the expedition got underway. For the rest of that summer and into the fall, these “Frenchmen” helped row, pole, and tow the boats up to the Mandan country. They also helped to hunt and perhaps to identify the geography of the Missouri River valley. Unfortunately, the journals of Lewis and Clark rarely mention these men by name, much less credit them individually.

The few journal entries concerning them are sketchy at best. Because these boatmen were not soldiers, a lower standard of record keeping applied to them. A barrier of language and culture, as well as their being assigned to the red pirogue, isolated these engagés from the rest of the party. Lewis and Clark wrote little more than their numbers (sometimes contradicting each other) and their names (with varying spelling) or simply referred to them as the “French.”

On 2 May 1804, Lewis wrote to Clark that “Mr. Choteau has procured seven engagés to go as far as the Mandanes—but they will not agree to go further . . . .”[2]Donald Jackson, ed. Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1962). Presumably these seven, plus a few more, accompanied the Corps upriver. The detachment order of 26 May 1804 assigns eight of them to a separate mess unit; around nine were discharged in early November of that year in the Mandan country and of these, two or three volunteered to winter with the Corps before returning to St. Louis. Lewis’s 5 August 1807 account shows that five received back wages in St. Louis in 1805. Some were probably paid in cash upon their discharge at the Mandan villages.

St. Charles Borromeo Parish Archives

Nowhere in their journals or letters do Lewis and Clark reveal where these boatmen hailed from, or the intricate ties many had with each other and with the native tribes along the Missouri River. Clues to these questions lay hidden until recently in the archives of the St. Charles Borromeo parish of St. Charles, Missouri.

Many younger parishes have deposited their early records with the St. Louis Archdiocese and its staff of archivists, but St. Charles Borromeo has always retained its original documents. This has kept these records somewhat isolated and has discouraged systematic research.T his author’s book is the first work based on the entire archival collection. Some of the information below echoes that of Mr. Anton J. Pregaldin, a St. Louis researcher who generously shared his engagé findings with Charles G. Clarke, author of The Men of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1970). At that time, however, Pregaldin and other researchers did not find the registers uniformly translated, indexed, and converted to a more legible form than that of cramped and smudged handwriting in gall ink on parchment sheets.

Now that 200 years of information is available in block print and standard English, material previously overlooked has come to light. The earliest baptism, marriage, and burial registers help explain the identities and family connections of the following engagés: Jean Baptiste Deschamps, Charles Pineau, Charles Hébert, Paul Primeau, Jean Baptiste Lajeunesse, Etienne Malboeuf, and Pierre Roy.[3]The spellings of Pineau and Roy differ slightly from those used by Gary E. Moulton, editor of The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The author has retained the spelling used by the … Continue reading

The parish archives have nothing to say about the following “Frenchmen” also associated with the expedition—Pierre Cruzatte, François Labiche, Jean-Baptiste Lepage, Charles Caugee, John Collins, or someone called La Liberté—which suggests that these men were not from St. Charles.

The archives also suggest a composite of the engagé selected. With a few exceptions, Chouteau (or whoever did the actual recruiting) seems to have looked for relatively young men with few family obligations binding them to the settled world and kinship by blood or marriage with one of the Indian tribes along the Missouri River. Although the registers show that various eastern tribes frequented the area, only men with ties to the tribes out west, especially the Missourias, Arikaras, and Mountain Crows, were hired. Most of these men had close ties with at least one other expedition engagé, and several came back to the area afterward.

Founding of the Parish

First, a little background about St. Charles and the parish of its patron saint. Reputedly founded in 1769 by a French Canadian hunter named Louis Blanchette, the settlement was known as Les Petites Cotes (“The Little Hills”), until 1791. In November of that year the Spanish government renamed the village to honor King Charles IV, and dedicated its new log church under the protection of his spiritual patron, St. Charles Borromeo. Parish record keeping began the following year. (See “The Founding of St. Charles and Blanchette, its Founder,” by Ben L. Emmons, Missouri Historical Review, 18, published in July 1924).

In 1798, Father Leander Lusson took over as pastor and remained in St. Charles until late in 1804. Though not named in the expedition journals, Lusson was the priest whose services some of the Corps members attended on 20 May 1804—there simply was no other priest in the area.

The original territory of St. Charles Borromeo parish stretched north and west into the unknown. Almost all residents of St. Charles (whom Clark estimated in 1804 at 450) were at least nominal Catholics. Most were of French Canadian and/or Native American stock with close ties to one or more of the tribes of the Missouri River valley. Few could read or write. Although the Spanish government had granted lands liberally in the hope of discouraging the itinerant life of trapping and trading, agriculture did not catch on until later. In 1804, most able-bodied St. Charlesemen still went upriver during the warm months to make their living among the tribes. Some stayed longer.

The first priests and laymen serving the parish frequently noted details about the people they married, baptized, and buried, particularly their age and place of origin or tribal affiliation. Unions with Indian women were common. Founder Louis Blanchette married a woman of either the Osage or Pawnee tribe, and one of his cousins—the father of engagé Etienne Malboeuf—had a marriage of sorts with a woman of the faraway Mountain Crow tribe. By the time Lewis and Clark arrived, St. Charles had a high percentage of families with some Native American blood.

Among the civic leaders of the day were François Duquette and his wife, Marie Louise Bauvais, who lived on a hill overlooking the Missouri River. On 16 May 1804, Clark joined the couple for dinner at this “eligent Situation.” Closer to the river stood the church of upright logs, and around it stretched the parish cemetery. Although the journals do not mention the condition of either in 1804, a decade later the church was ramshackle and the cemetery almost full. After François Duquette died in 1816, his widow donated the grounds that Clark had so admired to the parish. The site became the home of a new St. Charles Borromeo church in 1828. Within a few years, the old log structure where Charles Pineau and the other engagés had knelt was gone and the surrounding cemetery closed. No apparent trace of either remains.

Most of the engagés noted in the archives made a home in or around St. Charles. Although their names are sometimes spelled in various ways (a visiting missionary, for example, renders Hébert “Eber”). They are identifiable by other details, such as the names of their spouses or parents. All of these men were absent from the parish registers during the time of the expedition. Some returned afterward and made their cross-shaped marks in the parish books.

Jean Baptiste Deschamps

Called “patroon”—foreman—this engagé was placed in charge of one of the pirogues and its cargo, a full-time responsibility which exempted him from guard duty. Deschamps was also the nominal leader of the French-speaking boatmen.

Why? The archives suggest that Deschamps may have been related to the wife of St. Charles’s top man of the time—Commandant Joseph Tayon. The Deschamps family was also one of the original families in the area. The first baptism in St. Louis occurred in 1766, to the child of a Deschamps woman.

Jean Baptiste lived with a local woman named Marie Anne Baguette, whose family name was called (hereafter dit) Langevin. The couple had several children. At the 1792 baptism of their son Jean Baptiste, the officiating priest noted that the mother was present but the father was absent. As the baptism occurred in the summer, Deschamps was probably upriver.

Deschamps and Marie Anne had other children whose names do not appear in the archives until many years later. In 1821, their daughter Cecile had her civil marriage ratified in the church. The following year when her sister Louise got married, the priest noted in the records that the bride had been born in St. Charles. As the typical St. Charles bride of that period was in her late teens, Louise probably was born around the time of the expedition. Similarly, when Cecile died and was buried in 1831, her age was listed as “around 26,” indicating that she was born in or around 1805.

Although he does not seem to have spent long intervals in St. Charles, Jean Baptiste Deschamp’s, evidently made a home and raised his family there. No mention of his son occurs after the boy’s baptism, but Deschamps’s daughters married and remained in St. Charles. Like most French-speakng local people of that time, Deschamps did not write his name but instead made a cross-shaped mark.

Charles Pineau

Though referred to as Pierre once by Clark, Pineau was listed as Charles upon being paid in St. Louis in 1805. No other mention is made except the 26 May 1804 detachment order placing Pineau and most of the other engagés in their own mess unit.

One week before the expedition got underway, an eighteen year-old named Charles Pineau presented himself for baptism at the log church. Father Lusson, who performed the ceremony, wrote that Pineau was the natural son of a Missouri Indian woman and the deceased Joseph Pineau, who had acknowledged paternity of Charles before he died.

Seeking baptism would have been logical for a young man of some Catholic upbringing about to leave the settled world.

A parish layman buried a Joseph Pineau in 1795, but failed to record his age or place of origin. Afterward, various Pineaus sought baptism at the church for themselves or for their children by Indian women, but no one by the name of Charles or Pierre.

It seems that Charles Pineau may have had a close tie with Jean Baptiste Deschamps. St. Louis parish archives list a Jean Baptiste Deschamps as the son of a man of the same name and a woman named Marie Pinot. Given the lack of standardized spelling and the fact that most residents back them could not read or write, “Pinoc” may refer to the Pineau family. Lewis’s financial records of the expedition lump these two boatmen together—the 7 October 1805 entry refers to payment being drawn on 28 May 1805 in favor of Deschamps and Charles Pineau.

Charles Hébert

This engagé spent much of his life in St. Charles as well as in Portage des Sioux, a rural hamlet located on the tongue of land between the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers in St. Charles County. Founded by the Spanish government in 1799, Portage des Sioux attracted farmers because of its rich bottomland and fur traders because of its strategic access to both rivers. Around the time of the expedition, many St. Charles people owned farmland in or near Portage des Sioux.

Charles Hébert was probably in his early thirties when he left with the expedition. Married in 1792, by 1804, he and his wife, Julie Hubert dit La Croix had at least one son and two daughters. Every year or two from 1797 to 1802, the couple had their latest arrival baptized by one of the Borromeo priests, who noted in the baptism archives that the family resided in St. Charles.

After 1802, Charles Hébert and his family disappear from the records until June of 1808, when a missionary visited Portage des Sioux and baptized several children, including one of Charles and Julie. This Hébert child had been born in May of 1807. A baby sister followed later in 1808 and another in 1811 ; thereafter the Héberts make no further appearance in the archives. Around this time, residents of Portage des Sioux built their own church.

The long interval between otherwise frequent births coincides with the expedition. The May, 1807 birth suggests that Hébert had returned home by August of 1806, but from the parish archives it is impossible to tell whether he returned with the November, 1804 contingent or waited until the following April—his cross-shaped mark is simply absent from the books between 1802 and 1808.

Paul Primeau

Called “Primaut,” “Premer,” and “Preemau” by the captains, this French Canadian left the expedition along with Jean Baptiste Lajeunesse and several others on 6 November 1804 for the Arikara nation and below. He married Pelagie Bissonet in 1799 in St. Louis. Clarke asserts that the couple went on to have 10 children, but the family does nor appear in the parish archives until long after the expedition, which suggests that they may not, have lived in St. Charles.

By 1807 Primeau had fallen into debt to George Drouillard and St. Louis’s maverick fur baron, Manuel Lisa, in the amount of almost $300. Clarke states that this debt was apparently paid off in 1808.

Twenty-one years later, Paul and Pelagie appeared in St. Charles for the wedding of their son Joseph to a local girl. The nuptials took place in a large stone church which replaced the log church in 1828. Built on the tract granted by François and Marie Louise Duquette, the structure had a plastered interior and was considered the most elegant house of worship for miles around. A young Belgian Jesuit named John B. Smedts (a classmate of the famous Father Pierre DeSmet, who during his long career ministered to some of the same tribes encountered by the expedition) united the couple. Like most other newcomers, Smedts struggled with the hybrid French of the area, spelling the groom’s name “Primant.” And like the other engagés, Paul Primeau used a cross-shaped mark to sign his name.

Jean Baptiste Lajeunesse

Married in St. Louis in 1797 to Elisabeth Malboeuf, the daughter of a French Canadian and a Mandan woman, this boatman was the brother-in-law of engagé Etienne Malboeuf. Just as the 7 October 1805 entry in Lewis’s financial records pairs Jean Baptiste Deschamps and Charles Pineau, the 4 October 1805 entry pairs Lajeunesse and Malboeuf.

The parish archives show that Lajeunesse and his wife lived in St. Charles and had at least two children by the time of the expedition. One was a boy named Jean Baptiste, for whom Etienne Malboeuf stood as godfather in 1802.

They also show that an unnamed child of Lajeunesse and his wife died at the age of six months and was buried in late November of 1805. Unless the writer erred as to the child’s age or parentage, this child would have been born in May or June of 1805, and therefore conceived in the fall of 1804. This is hard to square with the assumption that Lajeunesse spent the winter upriver.

Another child was born on 6 March 1807, but by the time she was baptized that November her father had died. One of the parish laymen buried Jean Baptiste Lajeunesse on 4 May 1807 and listed his age as “around 45.” His widow married another St. Charles man in September of that year.

Jean Baptiste Lajeunesse, Jr. evidently made his living upriver. He reappears in the archives for the 1834 wedding of a friend, and again the following spring for his own wedding. This entry, dated 9 February 1835, reveals that the trapping and trading way of life persisted in St. Charles among the old French Canadian families. The officiating priest wrote that “after one publication [of the customary three banns of matrimony], dispensation having been given from the others (the husband leaves on a trip in April), I have received the mutual consent of marriage from Mr. Baptiste La Jenesse and Madame Emilie . . . ” The inability to sign names persisted, too.

Etienne Malboeuf

Son of a French Canadian and a woman listed in his baptismal entry as “Josephe de Bel Homme of the Mountain Crow nation,” this engagé came from an astonishingly well-traveled family. The Mountain branch of the Crow tribe lived in south-central Montana—the very fringe of the world known to whites when Etienne was born.

The Malboeufs were also well-connected in St. Charles, being cousins of founder and commandant Louis Blanchette. A Pelagie Bissonet—perhaps the woman who later married Paul Primeau—served as godmother to one of Etienne’s younger brothers in 1792.

Etienne and five siblings were baptized in the log church between 1792 and 1795. Although François Malboeuf is noted as the father of each, the mother is noted variously as a Mountain Crow called “Josephe Beau Savage,” as well as “Josephine Crise, Savage of the Mountain Crow nation on the Missouri,” and “Josephine, a Savage.”

Etienne’s father died in January of 1804. His burial entry gives his age as about 72 years, and adds that the French Canadian had died in the home of his son-in-law, Jean Baptiste Lajeunesse. No mention is made of a surviving spouse, suggesting either than François survived the mother(s) of his children, or that he had not been canonically married.

Etienne Malboeuf received payment in 1805 for his services co the expedition, but whether he returned to St. Charles is not known. There simply is no further mention of him or his children in the parish archives after 1804, in contrast to the many entries of the previous decade.

Pierre Roy

Also called Roi, Roie, and Le Roy in the journals, this engagé has been one of the hardest to identify. Clarke suggests that he may have been the son of a Ste. Genevieve man named Pierre Roy, whose wife had a son by that name in 1786.

A different Pierre Roy was baptized and married in the log church and lost his wife a few months before the expedition departed. This Roy [the y in whose name may be explainable if Father Lusson used the spelling of the Provence region of France] received baptism in 1794 at the age of 14, although the officiating priest failed to note his parentage.

On 11 October 1803, Pierre Roy, “legitimate and majority age son of Pierre Roy and the deceased Josette La Pointe . . . native of the Beaumont Parish, diocese of Quebec in Canada and resident of this parish” married Marie Louise Vallé, “legitimate and minor daughter of Jean Baptiste Vallé and Therese, Indienne, her father and mother, residents of this parish.” The bride may very well have been the daughter of the trader Jean Vallé who had already been upriver for about a year when he encountered the Corps on 1 October 1804 and passed along valuable information about the Cheyenne country and the Arikaras.

If so, he came by such information honestly. Roy’s mother-in-law, Therese Vallé, was an Arikara. She and Jean Baptiste made their home in St. Charles, despite Vallé’s frequent absences, one of which kept him from his daughter’s wedding to Roy. The bride instead proceeded “under the authority and consent of [a local man] and her said mother . . . her father being absent.” Witnessing the wedding were engagés François Malboeuf and Jean Baptiste Lajeunesse. ln December of 1803, Marie Louise Vallé Roy was buried in the parish cemetery. Father Lusson listed her age as around nineteen.

Her mother, Therese the Arikara, joined her the following August. Therese’s burial entry states that she died in the home of a local fur trader, which suggests that her husband was not around to care for her during her last illness.

What happened to Roy after the expedition is not known. His cross-shaped mark does not appear in the records after 1804.

“Rokey”

There may have been a separate engagé to whom Clark referred as “Rokey” on 21 August 1806 when the expedition returned to the Arikara villages. This engagé seems to have stayed behind when the others, discharged in 1805, returned to St. Louis.

Moulton postulates that this “Rokey” was really Pierre Roi (Roy). Given the recent death of Roy’s wife, it seems reasonable that he would have stayed upriver; the couple had no children. Further-more, Roy was one of the engagés who did not collect his pay in St. Louis in 1 805.

But in case there was another French-speaking boatman referred to as “Rokey,” the composite established by the parish archives suggests a possible identity.

He could have been a St. Charlesan named Augustin Joseph Rhoc, the natural son of a French Canadian named Joseph Rhoc and a Sioux woman called “La Bleue.” This Augustin was baptized on 19 May 1798 in the presence of his father. He was then around 13 and would therefore have been of prime age to accompany the expedition six years later.

This Augustin may have lost his father in January of 1804. Father Lusson recorded the burial of an elderly French Canadian named Augustin Rhoc. There is no further mention of this family.

Conclusion

This sketch of Augustin Rhoc illustrates the characteristics of many, but not all, of the engagés discussed above: a Native American mother or wife, affiliation through her with a Missouri River tribe, and freedom from family obligation caused by the recent death of a loved one.

St. Charles was the logical place to seek qualified boatmen. The village had more fur trappers and traders per capita than most other settlements in the Mississippi Valley. Their way of life—going upriver for many months—persisted in St. Charles after it had died out elsewhere. In the 1820s and 1830s, Pierre Desmet and his fellow Jesuits despaired of the local men ever settling down to farming instead of abandoning their wives and children every spring co go upriver.

St. Charles was clearly the home in 1804 of Deschamps, Hébert, Malboeuf, Lajeunesse, and Roy. It may also have been the home, at least for a time, of the others discussed.

The St. Charles Borromeo archives prove that even before the expedition, many of the engagés had become tightly knit. They married into each other’s families, witnessed each other’s weddings and baptisms, and nursed each other’s sick. This tradition probably continued long after the expedition.

For Further Reading

Jo Ann Brown (Trogdon), St. Charles Borromeo, 200 Years of Faith Parish Records, vol. 1 and 2 (Patrice Press, 1991).

Jo Ann Trogdon, The Unknown Travels and Dubious Pursuits of William Clark (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2015)

Today, the St. Charles Historic District is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service.—ed.

Notes

| ↑1 | Jo Ann Brown-Trogdon, “New Light on Some of the Expedition Engagés”, We Proceeded On, August 1996, Volume 22, Nos. 3, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original article is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol22no3.pdf#page=14. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Donald Jackson, ed. Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1962). |

| ↑3 | The spellings of Pineau and Roy differ slightly from those used by Gary E. Moulton, editor of The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The author has retained the spelling used by the French-born priest who ministered to these men and their families.) |