It was no coincidence that Lewis was the first to see the Great Falls or the Continental Divide; he wanted to be a solitary hero.

Foreword by Clay Jenkinson (excerpt)

River of Promise is in a sense several books at once, or perhaps one book with several interlocking argumentative strategies. It is, first and foremost, a nuanced and insightful examination of the least well known portion of the journey, the transit from Weippe Prairie (the western terminus of the Bitterroot Mountains) to the Pacific Ocean and back again. Nicandri rightly bewails the general falling off of Lewis and Clark historical narratives after the expedition reaches the source of the “mighty and heretofore deemed endless Missouri River,” certainly after the expedition began to float with rather than against the current. The usual historiographical strategy, to focus on the outbound journey at the expense of the return (mere denouement in most accounts), and to wrap things up pretty quickly after Lewis triumphs, 22 September 1805, over “those tremendous mountains,” has had two serious negative consequences, aside from the obvious shortcoming of ignoring a leg of the trail that deserves its fair share of attention.

First, given our multiculturalist interest in the expedition’s encounters with Native Americans, the usual narrative peters out just when things get really interesting, when the expedition reaches a region with dense Indian populations. Historians used to say, a little erroneously, that Lewis and Clark did not encounter a single Indian between Fort Mandan, in today’s North Dakota, and the Shoshone on the Montana-Idaho border (a distance of 700 miles, and a temporal span of 128 days). Now, suddenly, in the Columbia basin, Lewis and Clark encounter so many Indians of so many tribes and sub-tribes that it is virtually impossible to keep them sorted out in one’s mind, like the characters of Tolstoy’s novels. This crowding of the historical stage occurs just when most historians stop paying close attention. River of Promise fills the Columbia River void admirably and re-peoples the landscape.

Second, Nicandri argues, rightly I believe, that it is simply impossible to understand the decline and death of Meriwether Lewis in the expedition’s aftermath without examining his spiritual exhaustion and the effective collapse of his authority (not to mention authorship) somewhere west of the Continental Divide. Lewis’s flurry of journal entries at Fort Clatsop beginning on January 1, 1806, literally has the feel of a New Year’s Resolution. But Lewis proves unable to sustain the project. He writes rather dutifully along the return trail, but there is a palpable falling off of energy, insight, and–above all–good will. The muffling of Lewis’s muse on the return journey is deafening. It robs the expedition of its most interesting voice. Clark’s return journal makes clear, in a loyal friend’s understated way,that Lewis was coming undone on the return journey. His patience with the strange ways of Indians was effectively at an end. Lewis was now openly voicing his darkest fantasies about the savagery of Indians. His famous outburst on February 20, 1806, (“never place our selves at the mercy of any savages. We well know, that the treachery of the aborigines of America and the too great confidence of our countreymen in their sincerity and friendship has caused the destruction of many hundreds of us.”) was not out of character at all, but a revelation of a deep-seated attitude. Lewis’s deep devotion to the Enlightenment President’s philanthropic principles and progressive agenda had forced his shadow distrust of savagery and his fundamental racism (what might more generously be called his race distaste) under the radar for much of the outbound journey, but Jeffersonian good will and cheerfulness could not be sustained much beyond the moment when Lewis shed the last integuments of Euro-American civilization as he stood, “a perfect Indian in appearance,” face to face with Cameahwait, “completely metamorphosed” by his journey into the heart of American darkness (August 16, 1805).

Nicandri’s point is that if you want to understand Lewis’s post-expeditionary spiral into defiant silence, political squabbling, failure to process his territorial finances in a way that satisfied the War Department, drink, “fusty, musty rusty” lovelessness, and estrangement from even Jefferson, you cannot begin with the hostilities and ineptitude of territorial secretary Frederic Bates and President Madison’s Secretary of War William Eustis. If you wish to understand the unraveling of the character of Meriwether Lewis, you must study the journals with microscopic attentiveness to mood and revelation, particularly those written after he left the source of the Missouri River. It can be argued that the greatest days of Lewis’s life were passed between June 13, 1805, when he “discovered” the Great Falls of the Missouri, and August 16, when he exchanged his tricorn hat and his rifle for Cameahwait’s tippet. After that, whatever had once made Lewis preen like “those deservedly famed adventurers,” Columbus or Captain Cook, diminished rapidly. Nicandri’s underlying point is that the Lewis and Clark community’s failure to make sense of Lewis’s undoubted suicide has as much to do with neglect of the Columbia basin experience as it does with America’s distaste for dark endings to otherwise triumphant stories.

Some may think that Nicandri pushes a little to far in trying to pinpoint the experiences that deconstructed Lewis, but he is surely right in his larger assertion that to understand the sad death of Meriwether Lewis we must first learn to read the journals, particularly the Pacific watershed journals, with fresh scrutiny and fewer preconceived notions about how an American explorer completes his journey. It is easy enough to reject Thomas Slaughter’s melodramatic assertion that Lewis “was already dead; only his body was still alive,” by the time he got back to St. Louis. But it is much harder to deny Nicandri’s argument that it is irrational and counter-textual to claim, as many, including Stephen Ambrose, have, that Lewis was fully intact when he strode into St. Louis on September 23, 1806, and that his downward spiral during the three succeeding years, the last years of his life, was unrelated to his experiences in the wilderness.

Part 1

William Clark’s explanation of Meriwether Lewis’s decision to leave Dismal Nitch deserves expanded scrutiny. Doing so sheds considerable light upon the actual working relationship between the two men, in contrast to the bromides frequently offered about their harmonious co-captaincy. Consider first that Lewis’s “object” in this undertaking, according to Clark, was to “examine if any white men were below within our reach.” This explanation strains credulity. John Colter had just returned from the bay around “Point Distress” and said that no traders or explorers were to be found. Colter would hardly have missed sighting ships around Point Distress if there had been any. Pvt. Joseph Whitehouse says Lewis ventured off to visit the Indian village Colter saw at the mouth of the river—abandoned at the time—an even less credible scenario.[1]JLCE [The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition], 6:46; 11:393.

There is a more plausible explanation for Lewis’s evacuation from Dismal Nitch. The broad pattern of Lewis’s behavior over the course of the journey suggests his motivation was narrow and purely personal. Colter’s report upon his return to Dismal Nitch that Alexander Willard and George Shannon were proceeding west along that “sandy beech” makes plain the risk that someone other than Lewis might be credited with the ultimate moment of discovery—reaching the Pacific and that first dramatic and completely open view of the ocean. Lewis had nearly all the other epochal moments of discovery to himself. He’d been the first to see the Great Falls of the Missouri, and he had taken that legendary first glimpse into the Columbia country from the crest of the Continental Divide. Would he allow an enlisted man to beat him to the western edge of the continent? Lewis developed a case of what mountaineers call “summit fever.”

Several clues substantiate this thesis. First, there is the curious phrasing Clark used to describe Lewis leading an advance party out of Dismal Nitch. Contrary to the usual practice of characterizing all major decisions through the use of the semantically inclusive “we,” Clark states forthrightly that “Capt Lewis concluded” on this course of action. Then there is the note Lewis posted at Fort Clatsop just prior to its abandonment in March of 1806, hoping that some “civilized person” might stumble upon the fort with his note still attached to its walls. Thereby the “informed world” would learn of the expedition, “sent out by the government of the U’ States,” that had penetrated the continent by way of the Missouri and Columbia Rivers “to the discharge of the latter into the Pacific Ocean, where they arrived on the 14th November, 1805″ (emphasis added). This date was purposively misleading on two counts. The great preponderance of the party on 14 November was still marooned east of Point Distress. William Clark and the bulk of the detachment would not successfully depart Dismal Nitch for another day. Secondly, the Colter party, as previously described, rounded Point Distress, the last impediment to westward travel, on the 13th.[2]Ambrose, Undaunted Courage, p. 308; JLCE, 6:47, 429.

Lewis had made a habit of abandoning Clark, as he did again at Dismal Nitch, in quests for exploratory triumph. It was no coincidence that Lewis was the first to see the Great Falls or the Continental Divide; he engineered those moments. As Stephen Beckham phrases it, Lewis “was quick to ‘jump ship’ and dash for the prizes of discovery.” Clay Jenkinson was the first scholar to note this tendency observing that “Lewis took command at critical moments in the Expedition. He seems to have wanted to make the great discoveries of the Expedition alone.” Lewis, Jenkinson writes, was a man “who struck poses.” He had studied the role of explorer well, notably as enacted by Alexander Mackenzie, as detail at length elsewhere in River of Promise.”[3]Beckham, Rockies to the Pacific, p. 64; Jenkinson, Lewis, pp. 9, 50.

For most explorers this egotism would not have presented much of a problem. Lewis, however, had a co-commander. As noted in the earlier discussion about the expedition’s Rocky Mountain “geography lesson,” the lore of Lewis & Clark holds that the captains always saw eye to eye. There were, in truth, no overt disturbances in what Gary Moulton terms “their remarkably harmonious relationship,” and from this he concluded “Lewis apparently treated Clark as . . . a partner whose abilities were complementary to his own.” But appearances can be deceiving. A deconstruction of the journals proves that Clark was occasionally disappointed by Lewis’s behavior and possibly annoyed to the point of resentment.[4]JLCE, 2:6; Jenkinson, Lewis, p. 52.

From the beginning of the venture Clark was disadvantaged by his relationship to Lewis. Clark shared in the command of the expedition, Clay Jenkinson writes, “by virtue of Meriwether Lewis’s magnanimity rather than in actual rank.” Lewis had failed to deliver on Clark’s promised promotion from lieutenant to captain. This gaffe resulted in both men having to pretend Clark was equal to Lewis in actual rank. Consequently, it should not surprise us that Clark, co-commander only because of an invitation from the (younger) man holding the original commission from the president, had been, as James Holmberg states, “very conscious of titles, rank, and his pride.” Clark later reminded Nicholas Biddle that in rank and command he was “equal in every point of view” (emphasis in the original). When considered in conjunction with the larger body of Clark’s crafty edits, demurrals, and disavowals in his own record plus those he later edited into Lewis’s journals, his post-expeditionary comment to Biddle was tantamount to a protest. Clark was insistent that posterity not see his work in the field as that of a second in command or a junior officer even if in reality his rank was lower than Lewis’s, as those in power in the nation’s capital would have known too well.[5]Jenkinson, Lewis, p. 53; Holmberg, Letters of William Clark, p. 72; Jackson, Letters, 2:571.

As we saw in an earlier chapter and shall again later in this one, Clark was able to partially correct or otherwise recalibrate the record so as to more accurately reflect his contributions to the expedition. Clark never had access to certain documents (e.g., manuscripts other than the journals), and when Lewis went un-braked there is no doubt about whose expedition it was. Lewis’s letter to his friend James Findley, sent downstream when the expedition was halfway up the Missouri in 1804, refers to “my party . . . of twenty-six healthy, robust, active young men, accustomed to fatiegue and danger.” Presumably William Clark, not mentioned as being on the voyage let alone being co-commander, was to be considered among that number. Then, in a private letter to his mother written shortly before the expedition left Fort Mandan in the spring of 1805, Lewis described having “arrived at this place . . . with the party under my command” (emphasis added). Excluding Clark may have been understandable if not excusable while writing to a friend or a close family member. However, Lewis later published a prospectus for the forthcoming account of travels and took credit not only for the prospective narrative but also the master map, which work had always been Clark’s specialty. This map was to be compiled “from the collective information of the best informed travellers through the various portions of that region, and corrected by a series of several hundred celestial observations, made by Captain Lewis during his late tour” (emphasis added). This was double diminution of Clark’s role: Lewis deigned to correct Clark while at the same time minimizing his primary contribution. It was precisely this hauteur that David McKeehan skewered in defense of his right to publish Sgt. Patrick Gass‘s journal in the face of Lewis’s opposition to unauthorized accounts of the expedition.[6]Holmberg, “Fairly Launched,” p. 22; Jackson, Letters, 1:222; 2:396. See Ibid., pp. 399-407 for McKeehan’s critique of Lewis. Allen, Lewis and Clark, p. 373 n. 39. The monument at … Continue reading

Though the expedition’s journals have the surface appearance of being an empirical chronology of events, they are, often as not, autobiography. In her explication of the exploratory genre, Barbara Belyea distinguishes between the narrative form of “the ‘I’ who writes and the ‘me’ who is written about.” Inevitably, Belyea states, the explorer as writer becomes “the main textual subject.” Though this literary phenomenon was the norm for explorers, Lewis took it to extremes. Consider, for example, Lewis’s famous description of the scene when the expedition left Fort Mandan. First, Lewis explicitly refers to Columbus and Cook (and inadvertently or otherwise to Alexander Mackenzie as well via his expropriation of the term “darling project,” as described at length in the chapter after next). He then introduces the excitement associated with entering “a country at least two thousand miles in width, on which the foot of civillized man had never trodden.” Next, Lewis wrote, “I could but esteem this moment of my departure as among the most happy of my life” (emphasis added). Framing this sentence Lewis consciously struck over the word “our” before “departure,” so the solitary construction was no accident. As Clay Jenkinson says, here “Lewis’s self-absorption is nearly complete.” Lewis reduced a moment of common endeavor to what Thomas Slaughter calls a “singular and possessive accomplishment” that had the effect of reducing poor Clark “to the status of crew.” Slaughter maintains that the ethos of exploration required of Lewis that he pose as the “singular hero.” Indeed, departing from Fort Mandan, Lewis effectively edited Clark out of the narrative. This is the inversion of an episode occurring a year earlier when the expedition left the Wood River wintering-over campsite of 1803–1804 on the Mississippi. On that occasion Lewis wrote himself into a story when in fact he wasn’t with the party on the first leg up the Missouri, joining it by going overland from St. Louis.[7]Belyea, Columbia Journals, p. xvii; JLCE, 4:9-10; Jenkinson, Lewis, p. 55; Slaughter, Exploring Lewis and Clark, pp. 36, 53.

As Clay Jenkinson avers, “at the critical moments of the Expedition, Lewis pushes the rest of the company out of his consciousness.” Lewis’s jumping ahead of Clark and leaving him at Dismal Nitch was a calculated stratagem in keeping with a tendency visible from the very beginning of the “collaboration” with Clark, aimed at putting himself in the historical spotlight should circumstances lend themselves to that eventuality. Consider, then, Clark’s plight. During the course of the expedition, he had to regularly bear the indignity of reading how Lewis constructed this posed narrative when making a copy of Lewis’s reflective journal entries.[8]Jenkinson, Lewis, p. 99.

The first notable instance of Lewis’s questing for glory west of Fort Mandan occurred during the approach to the Yellowstone River’s confluence with the Missouri–what Lewis termed a “long wished for spot”–on the present border between North Dakota and Montana. Unfavorable winds had been retarding the progress of the watercraft for several days in late April 1805. Knowing from the reports of the hunters out ahead that the Yellowstone was not far away, Lewis determined to avoid any further “detention.” He proceeded ahead by land with a few men “to the entrance of that river” to make the astronomical observations that would fix its position, “which I hoped to effect by the time that Capt. Clark could arrive with the party.” When Clark finally caught up they quibbled a bit over the best location for the emplacement of a future trading post.[9]JLCE, 4:66, 70, 77.

Several weeks later, past the Milk River confluence in present-day eastern Montana, Lewis began to fret about reaching the source of the Missouri. He was “extreemly anxious to get in view of the rocky mountains.” Clark’s journal for this segment of the journey is largely a verbatim reiteration of Lewis’s reflective notes, which makes differentiating Clark’s activities and thoughts from those of his co-commander unusually difficult. Clark’s rare deviations from Lewis’s text, and a few clues left by Lewis, help to discern the sequence of events leading up to the first sighting of the Rockies and who was to claim credit for doing so.[10]JLCE, 4:132. Moulton suggests that Clark composed this copy of Lewis’s journal at Fort Clatsop or on the return trip in 1806. Ibid., 4:200 n. 10.

Clark’s copy does not reiterate Lewis’s anxiety about seeing the mountains, for reasons that will become clear in our explication of the journals’ narrative of the ensuing fortnight. As chance would have it, a little more than a week later, on 19 May 1805, Clark ventured off on a solo ramble to the top of “the highest hill I could See.” From that vantage he viewed a “high mountain” to the west. After Clark’s return to the main party, Lewis reported this sighting in his journal, but the object therein was now more elaborately described as a “range of Mountains” with added detail gleaned from Clark about their extent and direction. Clark had seen the so-called Little Rocky Mountains of north central Montana. Five days later, Clark was again walking “on the high countrey” off the north bank of the Missouri. From that elevated vantage Clark saw what he termed the “North Mountns” and another chain to the south, the Judith Range, or in Clark’s terminology, the “South Mountains.” Lewis absorbed this intelligence and offered some speculations about the western mountains in his journal, but he did not venture to the heights himself.[11]JLCE, 4:134, 167-168, 169 n. 2, 189, 191, 192 nn. 4, 6.

Part 2

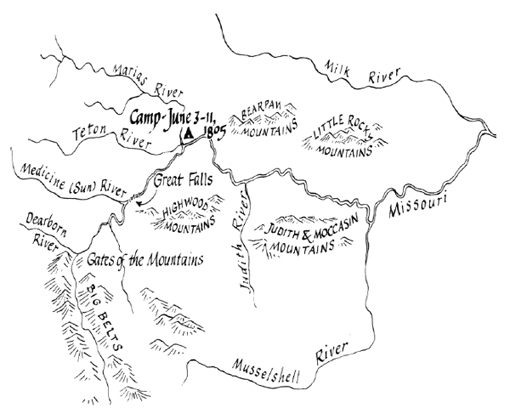

Rocky Mountains

Courtesy Dover Publications, Inc.

From Lewis and Clark and the Image of the American Northwest by John Logan Allen.

Contrary to geographical lore, the Rocky Mountains were many ranges deep in central and western Montana.

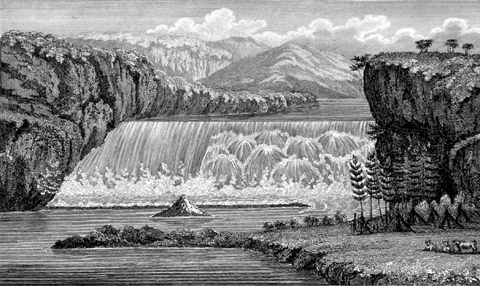

The Grand Fall

Courtesy of Watzek Library, Lewis & Clark College, Portland, Oregon

The strained sublimity of Meriwether Lewis’s description of the Great Falls of the Missouri inspired this engraving in a second generation edition of the expedition’s journals. The falls today are compromised by a dam and power plant.

Six days later, May 25th, during his “walk of this day,” Clark again viewed the mountains to the north and south but added, “I also think I saw a range of high mounts. at a great distance to the SSW. but am not certain as the horozon was not clear enough to view it with Certainty.” These were the Highwood Mountains near Great Falls, Montana. Lewis’s journal makes no mention of this sighting, which conveniently preserves the prospect of his discovering them, as we shall see. The next morning, 26 May 1805, Clark again “ascended the high countrey to view the mountains which I thought I Saw yesterday.” From his new perch “much higher than where I first viewed the above mountains [yesterday] . . . I beheld the Rocky Mountains for the first time with Certainty.” This line in Clark’s journal for that day marks the commencement of what is more generally his copy of Lewis’s remarks, deleting what would have been odd references back to himself in the third person, but of particular note here adding the phrase “with Certainty.” The point or value of this edit in Clark’s version is discernible when we see Lewis’s original record for the same day, a document that was recorded before Clark’s.[12]JLCE, 4:198, 200 n. 11, 203-204.

Lewis’s journal for May 26th first reports that “Capt. Clark walked on shore this morning” and in a rather pedestrian fashion recounts that his co-commander “had seen mountains,” a perspective vested with no particular significance for a reason soon made clear. Then, in “the after part of the day,” Lewis “also walked out and ascended the river hills,” following Clark’s lead and assuredly in response to his colleague’s findings. Once at the heights Lewis considered himself “well repaid” for his labors “as from this point I beheld the Rocky Mountains for the first time.” Again, Clark’s copy of this entry from Lewis’s transcript reads: “from this point I beheld the Rocky Mountains for the first time with Certainty” (emphasis added). What Clark had done here is to take Lewis’s narrative baseline and massage it to reinforce his own prior sighting on the day before. Lewis’s version proceeds to references of the “range of broken mountains seen this morning by Capt. C.” However this gesture is quickly followed by Lewis’s reversion to the form of the singular hero. Lewis recorded, “while I viewed these mountains I felt a secret pleasure in finding myself so near the head of the heretofore conceived boundless Missouri; but when I reflected on the difficulties which this snowey barrier would most probably throw my way to the Pacific, and the sufferings and hardships of myself and party in them, it in some measure counterballanced the joy I had felt in the first moments in which I gazed on them” (emphasis added). Clark dutifully copied all this Rocky Mountain Romance, but by subtly adding the words “with Certainty” at the outset of Lewis’s textual soliloquy, he quietly asserts his proper place in the story of the authoritative first sighting of the Rocky Mountains.[13]JLCE, 4:200, 201, 204.

Next, consider Lewis’s most famous discovery, the Great Falls of the Missouri. The Hidatsa told the captains that reaching this feature was the sure sign that they were on the correct route to the Columbia. This point was so axiomatic in the expedition’s understanding of western geography that it served as the solution to the quandary faced by the party at the surprising appearance of the Marias River. Then and there Pierre Cruzatte and the other men in the detachment forced the captains’ hands on the question of which branch of the river was the route to the headwaters of the river. Lewis complained that, contrary to his and Clark’s opinion, Cruzatte, “an old Missouri navigator . . . had acquired the confidence of every individual of the party . . . that the N. fork [the Marias] was the true genuine Missouri.” Indeed, the men were “so determined in this beleif, and wishing that if we were in error to be able to detect it and rectify it as soon as possible it was agreed between Capt. C. and myself that one of us should set out with a small party by land up the South fork [the Missouri] and continue our rout up it untill we found the falls.”[14]JLCE, 4:271.

Tensions now emerged within the joint command because of what Thomas Slaughter calls the conventions of exploration as a “solitary event.” As Lewis phrased it in his approximately 1,400-word account about the decision at the Marias, “this expedition [in search of the falls and thus the true Missouri] I prefered undertaking as Capt. C [is the] best waterman & c.” William Clark’s corresponding report numbers less than 200 words. Of Lewis’s decision to jump ahead, he writes tersely about effecting a cache of one pirogue, tools, powder and lead, and as soon as “accomplished to assend the South fork.” The absence of any nouns or pronouns in this last phrasing may be telling. His only mention of Lewis by name is to report that his co-commander was “a little unwell to day” and that he had to take “Salts & c.” This would be the start of another pattern—Lewis becoming ill on those occasions when the fate of the expedition seemed to hang in the balance, an equivalence in Lewis’s mind to his prospective reputation as a solitary and heroic explorer. Lewis described his illness as “disentary.”[15]Slaughter, Exploring Lewis and Clark, p. 29; JLCE, 4:271, 274, 275.

In Thomas Slaughter’s view, “companions create narrative problems for the explorer,” as we saw earlier with John Ordway‘s and Joseph Whitehouse’s candid expressions upon reaching the forks of the Columbia. In this case, when Lewis “jumped ship” on his quest for the Great Falls and exploratory glory, George Drouillard, Joseph Field, George Gibson, and Silas Goodrich accompanied him. However, a few days later, when Lewis encounters the “sublimely grand specticle” these men virtually disappear from the narrative. The experience with nature’s wonder is Lewis’s alone.[16]Slaughter, Exploring Lewis and Clark, p. 29; JLCE, 4:283.

Then later that summer, once the expedition reached the Three Forks of the Missouri, another great moment of discovery loomed–”seeing the head of the missouri yet unknown to the civilized world,” as Lewis phrased it, and the Continental Divide from which it sprang. During this segment of the trip Clark had been proceeding ahead of the flotilla on land with the hunters, and he relished being in the vanguard. We know this from Lewis himself who noted that “Capt C. was much fatiegued[,] his feet yet blistered and soar,” yet he “insisted on pursuing his rout in the morning nor weould he consent willingly to my releiving him at that time by taking a tour of the same kind” (emphasis added). This remarkably insightful entry becomes even more interesting when posed with Lewis’s next comment: “finding [Clark] anxious I readily consented to remain with the canoes.” Something more than Clark just toughing it out is clearly at play here. Even Nicholas Biddle sensed the tension and attempted to sanitize the account by substituting the more neutral “deturmined” for the vexatious “insisted” found in Lewis’s original text.[17]JLCE, 4:416-417.

Clark’s intention was “to proceed on in pursute of the Snake Indians,” the gatekeepers to the Rocky Mountain passage. An encounter with the Shoshone would have ensured Clark a central moment in the master narrative of the expedition’s glories. Lewis, two days behind Clark, knew that his co-commander had “pursued the Indian road,” had found an abandoned horse, and “saw much indian sign.” Meanwhile, Lewis and the balance of the expedition labored in poling and hauling the canoes over the riffles in the riverbed.[18]JLCE, 4:418, 423-424.

On July 25th Clark and his advance guard reached the Three Forks and then headed up what he termed the “main North fork” (later to be called the Jefferson River). This fork, Clark wrote expectantly, “affords a great Deel of water and appears to head in the Snow mountains.” Here was Clark’s main chance. Lewis himself observed that on the basis of a note left for him at the Three Forks, Clark was on a course “in the direction we were anxious to pursue.” Unfortunately for Clark, his continued exertions in defiance of blistered and bruised feet (the result of repeated exposure to prickly pears cactus) and a somewhat straitened diet (not so much from supply but opportunity to eat), combined with oppressive midsummer heat, made him sick. Suffering from a high fever and chills, constipated, and losing his appetite altogether because of the fatigue brought on by his vigorous march ahead of Lewis and the canoes, Clark turned back to the Three Forks, exhausted. There he met with Lewis and the flotilla heading up the Missouri.[19]JLCE, 4:427-428, 433 n. 9, 436.

For two days, 28–29 July 1805, Lewis doctored Clark at the Three Forks. Lewis had “a small bower or booth erected” for Clark’s comfort because the “leather lodge when exposed to the sun is excessively hot.” Clark’s fever dissipated slowly, and though the recovery had begun he complained “of a general soarness in all his limbs.” Lewis, however, was anxious to get going. On the 30th the detachment broke camp, but now it was Lewis on foot in that pivotal vanguard of hunters while Clark and the voyagers brought up the rear. After only one day with this arrangement, Lewis admitted having “waited at my camp very impatiently for the arrival of Capt. Clark and party.” Becoming by his own admission “uneasy” with this pattern, Lewis determined on the next day “to go in quest of the Snake Indians.” Packing away a sheaf of papers with which to record notes that might be adapted into a narrative worthy of posterity’s reading, Lewis took Drouillard, Charbonneau, and Sgt. Patrick Gass on this mission. Once again the excitement of becoming the exploratory hero brought on “a slight desentary,” as had happened to Lewis when he jumped ahead of Clark in pursuit of the Great Falls.[20]JLCE, 4:436; 5:8-9, 11, 17, 18, 25, 29 n. 1.

The day Lewis leapt ahead, August 1st, happened to be Clark’s birthday. Clark reported tersely and with a tinge of hurt, “Capt. Lewis left me at 8 oClock.” Left behind to slog up the gravelly bed of the Jefferson River with the canoes, Clark’s physical problems mounted when his ankle swelled. One day ahead of the main party, Lewis reached the forks of the Jefferson and determined that the affluent known today as the Beaverhead River, with its warmer water and gentler flow, was the more navigable route. Lewis deduced that the Beaverhead “had it’s source at a greater distance in the mountains and passed through an opener country than the other.” Lewis left a note for Clark on a pole at the Jefferson forks instructing him on the recommended route for the canoes in case he did not return to this spot before the main party got there.[21]JLCE, 5:29, 40.

Part 3

Once a few miles up the Beaverhead fork of the Jefferson, Lewis could now see that it headed in a “gap formed by it in the mountains.” With that promising prospect in front of him Lewis wrote, “I did not hesitate in beleiving the [Beaverhead] the most proper for us to ascend.” Better yet, “an old indian road very large and plain leads up this fork.” This was the path to the Shoshone, the Continental Divide, waters that drained to the Pacific, and to glory.[22]JLCE, 5:44-45, 51 n. 2.

Down below, Clark was barely able to walk. The “poleing men” and those hauling the canoes were “much fatigued from their excessive labours . . . verry weak being in the water all day.” After his initial reconnaissance of the Beaverhead, Lewis returned to the forks of the Jefferson River expecting to find “Capt. C. and the party . . . on their way up.” Lewis was dismayed because upon reaching the forks, he discerned that Clark had not taken the recommended route up the Beaverhead, but one to the northwest known today as the Big Hole River. Lewis sent Drouillard after him and later “learnt from Capt. Clark that he had not found the note which I had left for him at that place and the reasons which had induced him to ascend” the more rapid northwesterly branch. In a comic twist, a beaver had gnawed down the post holding Lewis’s directions with neardisastrous consequences for poor Clark, who had simply followed the stream with the greatest flow—a fundamental hydrological principle that had always guided the expedition.[23]JLCE, 5:43, 47, 52, 54.

Lewis reported that Clark pursued the “rapid fork” for nine miles, but after one of the canoes was “overset and all the baggage wet, the medecine box among other articles . . . lost,” including a shot pouch, powder horn, and a rifle, he decided to return to the forks of the Jefferson. By the time this retrograde movement was completed, two other canoes filled with water, dampening “a great part of our most valuable stores” including the all-valuable Indian presents. Pvt. Joseph Whitehouse had nearly been killed on this excursion when he was thrown out of one of the canoes which “pressed him to the bottom as she passed over him.” Had the water been two inches shallower, Lewis opined, the canoe “must inevitably have crushed him to death.” Fortunately, none of the lead canisters containing gun powder had been breached even “tho’ some of them had remained upwards of an hour under water.” (Any significant amount of moisture would have ruined this vital supply with potentially disastrous consequences for the sustainability or defense of the expedition.) After recounting this story, Lewis then credited himself for having conjured the system of storing powder in lead containers rather than wooden vessels.[24]JLCE, 5:52-53.

What Lewis referred to rather pointedly as Clark’s “mistake in the rivers” almost resulted in the loss of yet another man. Clark had sent George Shannon ahead to hunt before the decision to reverse course was made. Shannon, Lewis recounted, had the previous misfortune of being lost for fifteen days going up the Missouri the year before. Shannon found his way back to the party a few days later, and Whitehouse was alive if “in much pain,” but Clark’s spirits were as dampened as the baggage that had been under his care. Lewis, on the other hand, was reveling this day in his narrative on the naming of the affluents of the Jefferson River: the “Wisdom” and the “Philanthropy, in commemoration of two of those cardinal virtues” of the president who dispatched them. Clark recounts nary a word about this fanciful stuff in his journal’s reckoning of that dismal day. He rather sparingly reported instead about Drouillard catching up with him with the news that the route he was on “was impractiabl” and that “all the Indian roades” led up the fork that Lewis had scouted. Clark “accordingly Droped down to the forks where I met Capt Lewis & party,” he wrote with a hint of resignation. Clark’s sore ankle was “much wors than it has been,” the physical pain compounding the embarrassment of having taken the wrong turn.[25]JLCE, 5:53-55.

The captains traveled together for two days up the Beaverhead fork of the Jefferson, but by the end of the second day, 8 August 1805, Lewis had had enough. He decided to “leave the charge of the party, and the care of the lunar observations to Capt. Clark” while he would on the next day proceed ahead “with a small party to the source of the principal stream of this river and pass the mountains to the Columbia.” The boil or cyst on Clark’s ankle had “discharged a considerable quantity of matter,” but it was still swollen and left him in “considerable pain,” Lewis reported. The morning Lewis forged ahead “to examine the river above, find a portage if possible, also the Snake Indians,” Clark recorded a poignant observation tinged with resentment: “I Should have taken this trip had I have been able to march.”[26]JLCE, 5:59, 62-63.>

Clark’s expression is one of the most suggestive of any to be found in the millions of words in the journals of the expedition. It exudes chagrin about not being able to make contact with the Shoshone and more particularly the Columbia River. Furthermore, one can intuit from it that after Lewis’s previous forays in pursuit of the Yellowstone and the Great Falls, Clark for certain, and maybe both captains, had concluded it was his turn for glory. Elliott Coues was the first to observe that “Captain Clark was sadly disappointed at not being able to take the lead in the trip.” More recently Stephen Ambrose said, “Clark wanted to lead” this reconnaissance, but that in the end it would prove Lewis’s “most important mission.” This, of course, gets to the heart of what was bothering Clark.[27]Coues, History, 2:471 n.; Ambrose, Undaunted Courage, pp. 262, 264.

Part 4

These circumstances put the aforementioned corrections Clark made in Lewis’s continental “geography lesson” into very sharp relief (see chapter 2). Fate, in the form of an ulcerous sore, may have denied Clark the opportunity to be the first over the Continental Divide. But he was determined that Biddle should know that the true comprehension of the complex Rocky Mountain district was his work, not Lewis’s, demolishing the pretentious edifice Lewis had constructed in his journal. At the moment Lewis left Clark on the headwaters of the Missouri, Clark’s rendezvous with destiny dissipated. Everyone in the party saw the consequences. As John Ordway put it, Captain Lewis had gone on ahead “to make discoveries.”[28]JLCE, 9:199.

Three weeks later, when the expedition was about to leave the company of the Lemhi Shoshone, Lewis let slip his characteristic conceit when he referred, once again, to resuming what he called “my voyage.” Such egotism has been an easy target from as early as 1807 in the form of David McKeehan’s broadside defending the desire of his client, Patrick Gass, to publish an unofficial account of the voyage. Nevertheless, Lewis was not completely oblivious to his obligations to his friend and co-commander. Lewis later named the Clark Fork of the Columbia after him, in partial reciprocation for Clark having named the Lewis (Snake) River. But whereas Lewis had, in fact, been the first to the Columbia’s waters, Clark’s honor was a mere gratuity. As Elliott Coues observed, Clark had not been the proverbial “first white man” on the waters named for him, or at least, no more so than any other man in the expedition since the entire party crossed into the Bitterroot/Clark Fork watershed en masse.[29]JLCE, 5:173; Coues, History, 2:584, 585 n.

Throughout his joint venture with Lewis, William Clark’s modesty shone through, a virtue not easily credited to his partner. As we have seen, though, Clark was not averse to correcting the worst of Lewis’s self-indulgences by emphasizing his own contributions. In another telling instance, this one from the June 1806 return trip over the Lolo Trail, Clark’s “verbatim” copy of Lewis’s journal, in which Lewis had recounted the expedition’s first contact with the Nez Perce at Weippe Prairie, Clark corrected Lewis’s “we” (by which Lewis had included himself in Clark’s vanguard contact with the Nez Perce, though Lewis was in fact trailing well behind) to “I,” thus reinstating himself as the first to reach Weippe Prairie. (We can safely surmise that if the roles had been reversed and Lewis had been the first to Weippe, a singular “I” would have appeared in his original transcript.) However, Clark’s presence as a companion in exploration was merely the most obvious narrative problem for Lewis as the solitary discoverer. Also on the same return crossing of the Lolo Trail, Lewis wrote with his unlimited sense of self-importance, “I met with a plant the root of which the shoshones eat.” Clark the copyist balanced the record by noting that it was Sacagawea who “Collected a parcel of roots of which the Shoshones Eat,” in reference to the western spring beauty, a white flower.[30]JLCE, 8:7, 11, 50-51, 52 n. 1.

Years after the expedition Clark privately criticized Lewis for the predicament his co-captain had put him in, referencing the “trouble and expence” of getting the journals into print. Lewis, like a cowbird, truly had laid his eggs in Clark’s nest. But Clark, in the end, was up to this task, and possessing the advantage of having been the more diligent journal-keeper, he exercised the option of editing the expedition’s documentary record in several key instances to create a more accurate account of events. In this respect, Clark was both the expedition’s first historian and later the historian’s friend, for the benefit of posterity. We are left, then, to wonder: had Lewis lived to write the official account of the expedition, how would Clark have fared in that narrative? Evidence left in the proto-manuscript as reflected in Lewis’s notebook for the spring and summer of 1805 suggests he would have extolled Clark’s virtues and assistance, but he, Lewis, would have been the sole hero of the story.[31]Holmberg, Letters of William Clark, p. 236.

About River of Promise

A Bold Study of Lewis and Clark, the First Publication of the Dakota Institute Press

Lewis & Clark left Fort Mandan on April 7, 1805. Meriwether Lewis wrote, “We were now about to penetrate a country at least 2000 miles in width upon which the foot of civilized man had never trodden.” After a long winter on the northern Great Plains, the Expedition was about to enter upon what Lewis regarded as the discovery phase of the journey.

April 7, 2010 was chosen as the launch date for the first book published by The Dakota Institute Press, a division of the Fort Mandan Foundation. David Nicandri’s remarkable River of Promise: Lewis and Clark on the Columbia explores the experiences of the Expedition on the west side of the Continental Divide. Nicandri provides a superb—at times revisionist—analysis of the Expedition’s travels from Lemhi Pass to the mouth of the Columbia and back again.

Nicandri provides a narrative account and a fresh analysis of the least well understood segment of the journey. He challenges a number of what he regards as Lewis and Clark legends and myths, including the notion that Sacagawea was a “good will ambassador” for the Expedition, the view that Lewis and Clark maintained a friendship and co-captaincy of “perfect harmony,” and the notion that at Lemhi Pass Meriwether Lewis experienced a palpable disappointment when he saw ranges of mountains that he must still traverse before he reached navigable waters of the Columbia River system.

The author also attempts to make sense of Lewis’s mental decline in the Pacific Northwest, especially on the return journey up the Columbia in the spring of 1806. Nicandri, who unhesitatingly believes that Lewis committee suicide on October 11, 1809, carefully attempts to identify the seeds of that self-destruction at the far side of the North American continent.

“This is a book that every lover of the Lewis and Clark story will want to read,” says former Dakota Institute Press editor-in-chief Clay Jenkinson. “It’s an outstanding study of the least-written-about section of the trail. Nicandri is smart, clever, and thoughtful, and his writing is a pleasure to read. Not everyone will agree with all of his conclusions, but he has taken seriously the challenge of viewing what we all thought we knew with fresh eyes. He’s done all of us a great service. We are thrilled that this is our first book.”

What is the Dakota Institute Press?

The Fort Mandan Foundation created The Dakota Institute, a non-profit entity that makes documentary films, publishes books, creates exhibits, and conducts interviews with notable people.

The mission of the Dakota Institute Press is to publish three to five books per year on a range of subjects relating to Lewis and Clark, the history of the American West, the Missouri River basin, Great Plains history, the history of North Dakota, and the literature of the landscape included in the Louisiana Purchase.

The Dakota Institute Press is soliciting book ideas, treatments, and manuscripts from historians, biographers, geographers, anthropologists, archaeologists, students of Native American culture; and novelists, poets, essayists, and memoirists.

For more information, see http://www.fortmandan.com/dakota-institute/the-dakota-institute-press/.

© 2010 by the Dakota Institute Press

Notes

| ↑1 | JLCE [The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition], 6:46; 11:393. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ambrose, Undaunted Courage, p. 308; JLCE, 6:47, 429. |

| ↑3 | Beckham, Rockies to the Pacific, p. 64; Jenkinson, Lewis, pp. 9, 50. |

| ↑4 | JLCE, 2:6; Jenkinson, Lewis, p. 52. |

| ↑5 | Jenkinson, Lewis, p. 53; Holmberg, Letters of William Clark, p. 72; Jackson, Letters, 2:571. |

| ↑6 | Holmberg, “Fairly Launched,” p. 22; Jackson, Letters, 1:222; 2:396. See Ibid., pp. 399-407 for McKeehan’s critique of Lewis. Allen, Lewis and Clark, p. 373 n. 39. The monument at Lewis’s gravesite in Tennessee—erected in 1848—cites Lewis as “commander of the Expedition” to Oregon. Coues, History, 1:lx. Notes (Pages: 177–189) 325. |

| ↑7 | Belyea, Columbia Journals, p. xvii; JLCE, 4:9-10; Jenkinson, Lewis, p. 55; Slaughter, Exploring Lewis and Clark, pp. 36, 53. |

| ↑8 | Jenkinson, Lewis, p. 99. |

| ↑9 | JLCE, 4:66, 70, 77. |

| ↑10 | JLCE, 4:132. Moulton suggests that Clark composed this copy of Lewis’s journal at Fort Clatsop or on the return trip in 1806. Ibid., 4:200 n. 10. |

| ↑11 | JLCE, 4:134, 167-168, 169 n. 2, 189, 191, 192 nn. 4, 6. |

| ↑12 | JLCE, 4:198, 200 n. 11, 203-204. |

| ↑13 | JLCE, 4:200, 201, 204. |

| ↑14 | JLCE, 4:271. |

| ↑15 | Slaughter, Exploring Lewis and Clark, p. 29; JLCE, 4:271, 274, 275. |

| ↑16 | Slaughter, Exploring Lewis and Clark, p. 29; JLCE, 4:283. |

| ↑17 | JLCE, 4:416-417. |

| ↑18 | JLCE, 4:418, 423-424. |

| ↑19 | JLCE, 4:427-428, 433 n. 9, 436. |

| ↑20 | JLCE, 4:436; 5:8-9, 11, 17, 18, 25, 29 n. 1. |

| ↑21 | JLCE, 5:29, 40. |

| ↑22 | JLCE, 5:44-45, 51 n. 2. |

| ↑23 | JLCE, 5:43, 47, 52, 54. |

| ↑24 | JLCE, 5:52-53. |

| ↑25 | JLCE, 5:53-55. |

| ↑26 | JLCE, 5:59, 62-63. |

| ↑27 | Coues, History, 2:471 n.; Ambrose, Undaunted Courage, pp. 262, 264. |

| ↑28 | JLCE, 9:199. |

| ↑29 | JLCE, 5:173; Coues, History, 2:584, 585 n. |

| ↑30 | JLCE, 8:7, 11, 50-51, 52 n. 1. |

| ↑31 | Holmberg, Letters of William Clark, p. 236. |