Lost Trail Pass to Travelers’ Rest

In the evening of 9 September 1805, the Corps of Discovery arrived at the place where their guide Toby told them they had to turn west and begin a ten-sleep trek through the mountain range whose jagged peaks “covred thick with Snow” had towered above them for four days since they’d left Lemhi Shoshone country. The tribulations they suffered as recently as a week earlier would have been fresh in their minds—the grueling hours they had spent hacking and bushwhacking their way up the abrupt slopes among the headwaters of the North Fork of the Salmon River—”So Steep that the horses Could Screcly [scarcely] keep from Slipping down.” They would never forget the shivering they shared in snow and sleet that night, somewhere on the Bitterroot Divide.

It has been said, off the record, that well-meaning Toby had made things worse by losing his way, but it was more likely the captains’ fault. Toby would have led them along the Shoshones’ mainline trail, which would have taken them precisely where they needed to go—to the headwaters of the Bitterroot River. But, fearful of being led back into buffalo country instead of westward to the headwaters of the Columbia River, they insisted on scrambling “cross-country” up the canyon headwall.

The next day dawned brightly, and in moccasins frozen stiff they lurched down the north side of the ridge. At the broad mountain meadow that was soon to gain the name “Ross Hole”, they met a large party of well-dressed and congenial Salish, who were “light completed more So than Common for Indians” and spoke . and acquired a few good horses. The next day they proceeded down the river Lewis named for Captain Clark, and as the canyon floor broadened they rode for three more days past one of the most spectacular sections of the Bitterroot Mountain range—the jagged ridge-lines and peaks that lofted the western horizon high in the sky. It must have been a disquieting scene for them all, for they knew they would soon have to penetrate that rocky barrier. Could the challenge ahead be any worse than what they had just been through? It could be. And it would be. They had been warned. So, “the weather appearing settled and fair,” Lewis wrote, he and Clark “determined to halt the next day rest our horses and take some scelestial Observations. we called this Creek Travellers rest.”[1]In the 18th and 19th centuries, when travel was far more tedious and tiresome than we can now imagine, “Traveler’s Rest” was a welcoming, comforting name for inns and taverns. A few … Continue reading

Travelers’ Rest, Montana

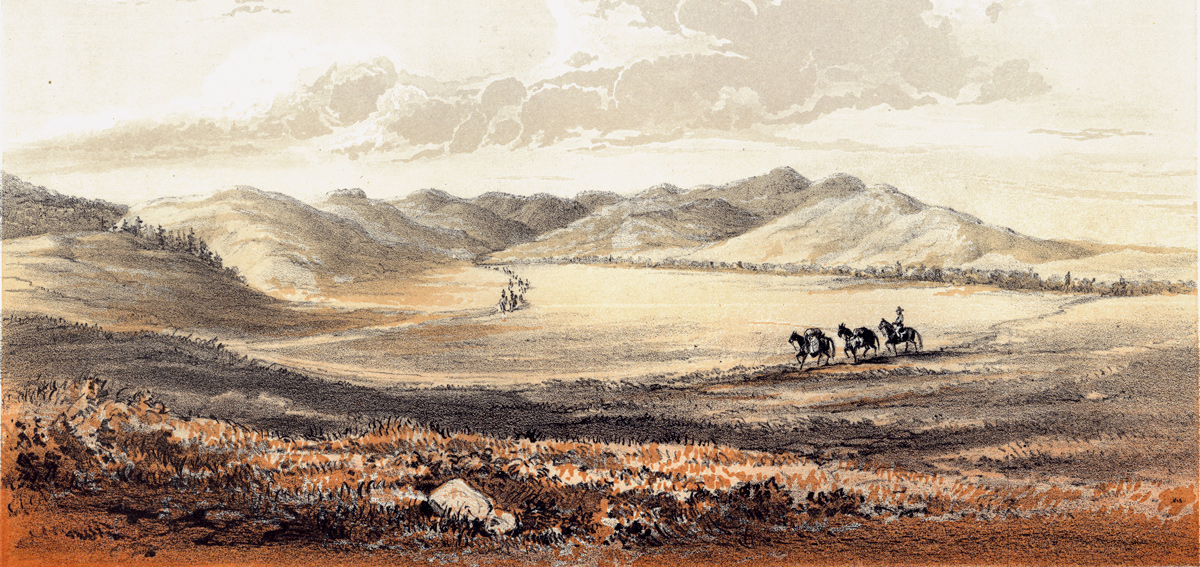

Entrance to the Bitter Root Mountains,

by the Lou Lou Fork

Chromolithograph by Gustavus Sohon (1825–1903), Reports of Expeditions and Surveys, Vol. 5, Plate 57.

The Campsite

To see labels, point to the map.

Library of Congress Geography and Map Division

Excerpt from Clark’s map, that accompanied the Nicholas Biddle-Paul Allen edition (1814) of the History of the Expedition.

Gustavus Sohon, one of two artists with Isaac Stevens’s railroad survey of 1853–55, was attached to Lieutenant John Mullan‘s detail, which Stevens directed to explore the Northern Nez Perce Trail across the Bitterroot Mountains, and estimate its viability as a possible route for this leg of the proposed railroad. In his report to Governor Stevens, Mullan noted that before proceeding up the trail they halted a few minutes at the mouth of the creek to allow Sohon to make a sketch of the “entrance to Lo-Lo’s Pass.” An Indian road corresponding roughly to the present U.S. Highway 93 is indicated in the foreground by two pack horses driven by a packer. The ancient trail westward up “Travelers-rest Creek” is represented by the long, orderly pack string heading west into the mountains. The camping place they called “Travelers-rest” would have been about where the string is entering the defile.

On his final map (1814) of the Expedition’s journey, Clark appears to have named only the creek “Travellers rest,” although it is slightly ambiguous. Probably he omitted his usual descriptive abbreviation “Cr.” due to lack of space, but there is no location symbol (a small dot, as with “Hot Springs” and “Canoe Camp”). Nor did anyone yet apply the name to the prominent peak that towered above their camp of 11 September 1805, nor to the hot springs, nor the pass on the Bitterroot Divide at the marshy, camas-rich meadow today called Packer Meadows.

Travelers’ Rest, South Carolina

To be sure, everyone needed a rest stop there—before going over and after coming back. However, aside from the name’s descriptive, utilitarian implications, there may have been a personal association behind Lewis’s choice of a name for this place. The looks of it, and the feelings it revived in him, may well have reminded him of the time when he, as an eight- or nine-year-old boy, along with his mother and stepfather, had to whip their draft animals up over the Blue Ridge Escarpment to get to their new home on the Broad River in Georgia. There would have been several ways to get there from the Lewis plantation up north in Albemarle, Virginia, but perhaps the most direct one would have taken them through the Piedmont Uplands to Greenville (at that time called Pleasantville), South Carolina, where ancient Indian roads converged at the foot of the defile leading westward across the mountains.

Like the place where the Corps of Discovery was to take a break before crossing the Bitterroots on 9–10 September 1805 and on 1-2 July 1806 after crossing back, that convergence in South Carolina was a long-established geopolitical node in the transportation and communication network of the region. It was a rendezvous, a gathering place, nine miles northwest of Greenville on the Reedy River. It was sometimes called Travelers’ Rest—a place to feed and water livestock, adjust packs and lace boots tighter, a place to let mind and body go limp for a day or so before starting a climb and a descent that offered no place to “recruit.”

The correspondences between that place and this may have inspired Lewis to invoke the name. If so, it was the only “transfer name” the captains ever used.

Nicholas Biddle’s paraphrase of the original journal entries covering the Bitterroot Mountains trek, laden as they were with blunt accounts of relentless labor, risk, hunger, cold, and bone-deep fatigue, were sufficiently ominous to make the most seasoned EuroAmerican traveler think twice about subjecting himself to it. All of those hardships and hazards were worsened by the remains of the winter’s snows on the return trip the following June. The Northern Nez Perce Trail was simply a bad road for anyone unaccustomed to it. There was little or no rest anywhere on it, for any traveler, man or beast.

There was bound to be a better mountain crossing. Or at least a better name.

Notes

| ↑1 | In the 18th and 19th centuries, when travel was far more tedious and tiresome than we can now imagine, “Traveler’s Rest” was a welcoming, comforting name for inns and taverns. A few of them are still in business in the British Isles. In the U.S. the name held broader connotations. There are 63 places listed in the Geographical Names Information System under the title “Travelers Rest,” most of them churches and cemeteries, with three historic post offices in Kentucky. (Genitive or possessive apostrophes are rarely included in GNIS entries because, according to the Board’s policy, “ownership of a feature is not in and of itself a reason to name a feature or change its name.”) Nearly all of the places in the GNIS named Travelers Rest are located in 9 southeastern states. Incidentally, there is a place called—either for locative clarity or whimsical irony—a Travelers Rest Correctional Center in Greenville, South Carolina, dating from 1993. The coincidence drawn here between the Travelers Rest at the foot of the Bitterroot Mountains in Montana and the ancient Indian resting-place at the foot of the Blue Ridge in South Carolina remains to be investigated more thoroughly. The site of the Marks’s home on the Broad River in Oglethorpe County was located in 1987 by Russell Slaton of Washington, Georgia. “Hidden history: On explorer’s trail in Oglethorpe.” The Athens, Georgia, Banner-Herald, 6 July 2003. |

|---|