The First Missionaries

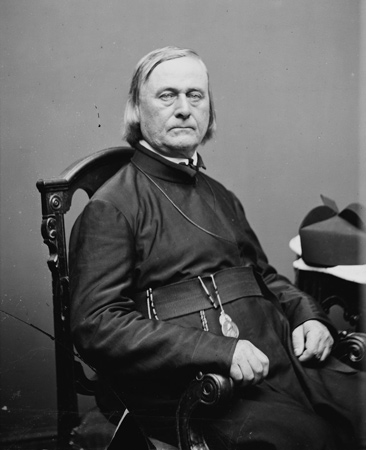

Father Pierre-Jean De Smet

by Mathew B. Brady (1822–1896)

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection. hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cwpbh.03561.

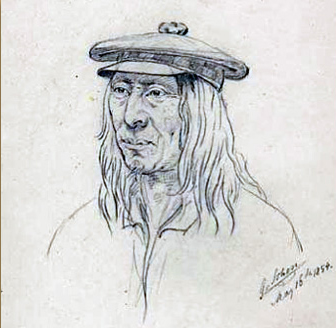

Aeneas, or Petit Ignace

The Black Robes’ Guide

Manuscript 130305C, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Aeneas appears to be a Greek name, although really it was a phonetic spelling of the Indians’ pronunciation of his baptismal name, Ignace, which in turn was the French version of the Italian Ignatius—after Saint Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Society of Jesus. We shall soon see that in one instance, at least, “Lolo” fell into the same category of Indian pronunciations of foreign names.

Gustavus Sohon (1825–1903), who drew this portrait in 1854 while he was with Lt. Mullan’s detachment, described his subject as a “poor, but an honest and reliable man.”

With the establishment of the North West Company in Montreal in 1784, the ensuing competition between the NWC and the Hudson’s Bay Company stimulated a rapid expansion of the fur trade in Canada and the contiguous British territories to the south, and increased the need for experienced trappers, as well as for strong canoe-men to ferry and portage supplies to far-western outposts and transport bales of hides back to headquarters. The first to respond were men of the Mohawk tribe of the Iroquois confederation, who had fled to Montreal after the American victory in the Revolutionary War. The first notable influx of Indian workers came in 1789, when some 250 Iroquois, Algonkins and Nipissings hired on with the NWC to work the upper Saskatchewan River out of Montreal as far west as today’s Edmonton, Alberta, and did so for lower wages than the French-Canadian voyageurs demanded.

The westward march of small brigades of independent-minded Iroquois continued. Sometime between 1812 and 1828 a band of about 24 of them, led by Ignace Lamoose, were invited to settle among the Flathead Indians in the Bitterroot Valley. Like all of the Iroquois, they had converted to Roman Catholicism before going west, and they openly practiced and preached their faith among their congenial hosts. Impressed and persuaded, the Flatheads soon gained an intense desire for the personal powers and blessings that the “Black Robes” could deliver. During the 1830s they sent four successive delegations to plead their cause at the diocese of Saint Louis. The fourth and last consisted of just two Iroquois, Pierre Gaucher and Aeneas, or Petit Ignace. The bishop approved their request, and Aeneas set out for the Bitterroot Valley with Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, of the Society of Jesus, with two other priests and three lay brothers, while Gaucher raced on ahead, by himself, to announce the Black Robes’ coming.[1]John Upton Terrell, The Arrow and the Cross: A History of the American Indian and the Missionaries (Santa Barbara: Capra Press, 1979, 205. At last, on 24 September 1841, Fr. De Smet jubilantly dedicated a tall cross to celebrate his party’s arrival and mark the site of the mission chapel they would build in the wilderness.

The Salish had waited so long to gain the guidance and ministrations of the Black Robes that they were virtually unanimous in the depth and energy of their dedication to the missionaries’ teachings. They were especially inspired by the exotic beauty of the first little chapel the Jesuits built.

The congregation grew rapidly. On December 3 of 1842, the feast day of St. Francis Xavier, the priests baptized 202 adults.[2]Lucylle H. Evans, St. Mary’s in the Rocky Mountains: A History of the Cradle of Montana’s Culture (Stevensville: Montana Creative Consultants, 1976), 5-31, 50. After a few years of radiant success, however, the ultimate futility of it all began to grow painfully clear. Harassments and threats by roving bands of Blackfeet Indians, some at the instigation of a few Flathead malcontents, made the future even darker. What many of the Salish really prayed for was guns, or at least for the miraculous failure of the Blackfeet guns. But the depredations continued, and the peace-loving Salish grew increasingly reluctant to permanently trade all of their traditional values for new and untried ones. Both their desires and the missionaries’ ambitions were culturally, politically, and spiritually premature. Late in the 1840s the deepening estrangement of the Indians from the Catholic church, accompanied by intermittent hostile acts by Blackfeet, Crow and Sioux warriors toward the priests and their followers, made immediate closure of the mission urgent.

Although both John Work and Father De Smet were–briefly, at least–very important figures in the early 19th-century history of the Indians’ northern trail across the Bitterroot Mountains, apparently neither of them encountered anyone named Lolo.

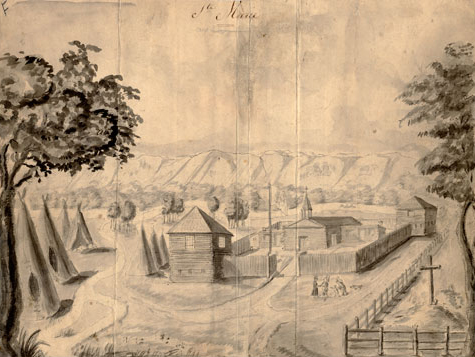

Father Point’s Illustrations

Father Nicolas Point (1799-1868) was chosen as the journalist and field artist for the Jesuits’ first mission in the Rocky Mountains. This drawing, made several weeks before the party of six priests and lay brothers, led by Fr. Jean-Pierre De Smet, arrived in the valley of the river (“Clark’s River”) that De Smet dedicated in honor of St. Mary. Fr. Point’s aim as an artist was not merely to create visual records of the west and its people, but to aid in teaching and encouraging the natives.

This drawing may have been used to show the prospective parishioners exactly what was to be built, and to encourage them to help. For the protection of the chapel and the residences of the missionaries from marauders, they were to be surrounded by a palisade, dominated by two bastions that would overlook the surrounding valley. Atop the pole at left of the main gate was to be the mission’s flag, which would the emblem that the Jesuit Order had adopted in 1541. At the center of the flag would be the monogram of Jesus, IHS, with a cross above it, all surrounded by a symbolic radiance of light.

In front of the compound, to the right of the gate, a “Blackrobe” shakes the hand of a Salish man. The Indian’s son is prepared to offer the priest a gift. Behind the boy, his mother carries a baby in a cradleboard. The family’s dog follows, carrying in his mouth some sort of a present, possibly a squash from the family garden. The party’s guide, Aeneas, could have coached Fr. Point in drawing the realistic outlines of the Bitterroot Mountains in the background.

To the left of the enclosure are seven tepees representing a mission colony called a “reduction,” where native converts to the new faith would be invited to live, apart from uncommitted natives as well from antagonistic non-Catholic white emigrants.

Precious Gifts

Unquestionably, Father Point was the most prolific of the early western artists. During the six years he spent in the Northwest he executed thousands of pen-and-ink and pencil drawings, and countless watercolors, although only 600 of the total are known to exist today.[3]Thomas M. Rochford, “Father Nicolas Point: Missionary and Artist,” Oregon Historical Quarterly, Vol. 97, No. 1 (Spring 1996), 46. He may have given some to his friends and associates in the northwest missions. A few may have gone to friends in St. Louis or back home in Europe. His illustrations of Rocky Mountain scenery, Indian life-ways and mission activities were documentaries for official records. Perhaps the images that were essentially didactic in purpose, such as his many drawings of saints’ lives and works, and his sketch of Saint Mary’s Mission, were simply used to pieces as teaching aids. The majority of portraits probably were given to their subjects. Imagine if you can how thrilling it would have been for an Indian man, woman or child to possess his or her own true-to-life image on a piece of paper. Just to sit for the portrait would have been to participate in the magic of it. The very paper that held it would have been precious.

Did Fr. Point draw our Lolo’s portrait? In view of the tremendous number of works he created, and the number that have been lost, the odds are that he did, but no copy of it exists today.

Among the most faithful of the missionaries’ converts to Catholicism was a half-breed trapper named Lolo who was killed by a grizzly bear in November 1850.

Notes

| ↑1 | John Upton Terrell, The Arrow and the Cross: A History of the American Indian and the Missionaries (Santa Barbara: Capra Press, 1979, 205. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Lucylle H. Evans, St. Mary’s in the Rocky Mountains: A History of the Cradle of Montana’s Culture (Stevensville: Montana Creative Consultants, 1976), 5-31, 50. |

| ↑3 | Thomas M. Rochford, “Father Nicolas Point: Missionary and Artist,” Oregon Historical Quarterly, Vol. 97, No. 1 (Spring 1996), 46. |