The Late Faithful Lolo

Father Joseph Joset, whose residence was at the Mission of the Sacred Heart beside the Coeur d’Alene River, was the Father Superior in charge of all four of the missions in the Rocky Mountains. In the autumn of 1850 he hurried to the Bitter Root valley to do what he could to help the priests and lay brothers in their crisis, and to supervise the closing of St. Mary’s. Upon arriving there at the end of October, Fr. Joset learned that nearly all of the Salish had lost faith in the church’s promises. All, that is, except one—”Lolo, the only Indian who still remained well disposed and really attached to religion.”

Lolo died after being horribly mangled by a grizzly bear a few days following Fr. Joset’s arrival.[1]Lucylle H. Evans, Good Samaritan of the Northwest: Anthony Ravalli, S.J., 1812-1884, Stevensville: Montana Creative Consultants, 1981), 102. Ralph Space recounted the tragedy as the venerable Nez Perce historian Harry Wheeler remembered being told of it:

Lolo and a Kootenai Indian companion . . . came upon a grizzly bear at close quarters. Lolo shot the bear but only wounded it. The bear charged. The Indian succeeded in getting up a tree, but the bear trapped Lolo under a windfall and dragged him out, almost tearing his left leg off. The Kootenai, who was armed with a bow, shot arrows into the bear until it left the area. Lolo was taken to his cabin, but he died and was buried beneath a beautiful grove of pine trees near the meadow.[2]Ralph Space, The Lolo Trail: A History and a Guide to the Trail of Lewis and Clark Second Edition (Missoula, Montana: Historic Montana Publishing, 2001), 8.

The probable site of Lolo’s demise was about 35 miles from St. Mary’s—more than a day’s travel each way—so the priests wouldn’t have had time to give the victim a Christian burial. But he might not have been entitled to one, after all. As a matter of course, the Jesuits would have referred to this ill-fated Lolo by his baptismal name if he had one, but Fr. Joset did not use it. Neither did Fr. Michael Accolti, S.J., who wrote to Fr. De Smet in 1852 concerning the fate of the Salish people: “The old generation of that once brave nation has passed away, even the good half-breed Lolo, who two years ago was attacked and devoured by some grizzly bears while hunting.” Consequently, it cannot be said with assurance that this Lolo was the one who 50 years later would be identified as “Lawrence.” In any case this steadfast Lolo deserved whatever measure of respect was accorded him. Having been struck down by a natural instrument of death may have been thought of as divine deliverance from the loneliness and rejection that might have been inflicted on him by his own people.

Deliverance

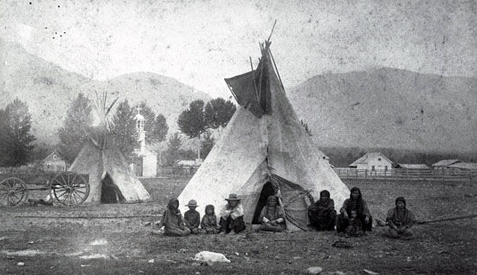

Salish camp at St. Mary’s Mission

Archives and Special Collections, Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library, University of Montana.

Above: Sometime between the late 1880s and the early 1900s, is a Salish family seated in front of their tepee. They are part of a “reduction,” a neighborhood of families encouraged to move their lodges to the immediate vicinity of the mission chapel. St. Mary’s chapel is at background left.

As if by divine intervention, Major John Owen appeared before the missionaries on November 5, 1850, and without hesitation leased their claims on the land, and purchased their improvements, including the cultivated fields and the mill, for a mere $250. It was understood that St. Mary’s might reopen at some propitious time in the future. Quickly the priests and lay brothers packed up and moved out, heading for the relative safety of the Kalispel Mission up in the Idaho panhandle. All of the portable effects from St. Mary’s—the instruments, mementos, anything that could be used again elsewhere—were loaded onto four wagons and three carts, with Father Joseph Joset and Brother Claessens in charge.

They spent the winter camped at the mouth of the Jocko River in the Flathead Valley where, with the help of some Indians, they built several flatboats and rafts to carry themselves and their goods down the Flathead and Clark Fork Rivers to their destination on Lake Coeur d’Alene. Unfortunately, the missionaries were ill-prepared for the risks involved in floating such large mountain rivers at the height of spring runoff. One craft was wrecked at Horse Prairie on the Clark Fork soon after they set out, and the rest were destroyed a few miles farther on, at Thompson Falls. Everything was lost, including the parish registers containing lists of all the sacramental acts the priests performed during the brief bloom of the first St. Mary’s Mission—baptisms, confirmations, weddings and burials.[3]Gilbert J. Garraghan, S.J., The Jesuits of the Middle United States, 3 vols. (New York: America Press, 1938), 2:386.

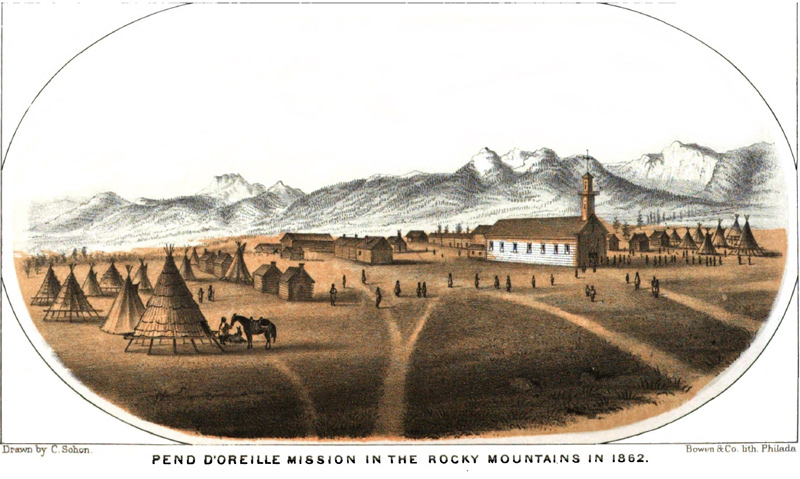

St. Ignatius Mission

by Gustavus Sohon (1825–1903)

Bowen & Co. lithograph. Originally titled “Pend d’Orielle Mission in the Rocky Mountains in 1862.” From Report and Maps of Captain John Mullan, Ex. Doc. No. 43. U.S. Senate. 37th Cong., 3d sess (Report). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, page 53.

Renascence

Within a year or two after the first St. Mary’s was closed, many of the Flatheads began to profess a change of heart, and pleaded for the blackrobes to return. That was impossible at the time, for the gold rush in California had imposed urgent new responsibilities on the Jesuits’ western missionaries. A few years later, however, like the Bitterroot plant, Lewisia rediviva), the native plant with the nutritious root and the delicate pink flower, that seems to die when the leaves and seed-heads have dried up and blown away, but which sprouts again each spring, the defunct St. Mary’s Mission sprang to life again in 1866.[4]Lucylle H. Evans, St. Mary’s in the Rocky Mountains: A History of the Cradle of Montana’s Culture (Stevensville, MT: Montana Creative Consultants. 1975), 123. The Father Superior for the Rocky Mountain region directed that St. Mary’s was to be rebuilt in the vicinity of its original location, with Father Anthony Ravalli as the rector. Father Jerome D’Aste took over from the ailing Ravalli in 1876, and faithfully kept records of parish events until 1891, when federal authorities forced the Salish people to abandon their valley homeland to make room for more white settlers, and walk 80 miles north to the vicinity of St. Ignatius Mission on the Flathead Reservation.

As the congregation of Indians and white settlers grew during the 1870s, further expansion of the chapel became necessary. The original section is the part now in the middle. Last to be built was the front section, which in 1879 doubled the interior dimensions to 18 feet, 10 inches in width and 46 feet in length. The facade was enhanced with whitewashed clapboards. The small but resonant 28-inch bell was shipped by freight wagon from a foundry in Cincinnati, and formally dedicated in the bell tower on 8 December 1879, by the congregation’s beloved physician, artist, architect, builder, sculptor and priest, Anthony Ravalli, SJ.

Father De Smet recorded his first impressions of the mountains that define the western horizon:

The mountains which terminate [the valley] on both sides appear to be inaccessible; they are piles of jagged rocks, the base of which presents nothing but fragments of the same description, while the Norwegian pine grows on those that are covered with earth, giving them a very sombre appearance, particularly in the autumn, in which season the snow begins to fall.[5]Pierre-Jean De Smet (1801-1873), “Letters and Sketches, 1841-1842”; reprint of original English edition; Philadelphia, 1843; in Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Early Western Travels, … Continue reading

The sheer face of the highest peak on western horizon, fringed with remnants of last winter’s snow, is the landmark Fr. De Smet named “Saint Mary’s.”

Sacramental Records

The sacramental records of the second St. Mary’s have survived, and although they were originally private, not public, documents, they have been translated and republished as historic resources.[6]Robert Bigart, Life and Death at St. Mary’s Mission, Montana: Births, Marriages, Deaths, and Survival among the Bitterroot Salish Indians, 1866-1891 (Pablo, Montana: Salish-Kootenai College … Continue reading They were written in Latin by a number of different priests in succession, each with his own style of handwriting, which means that it is often difficult, and in a few cases impossible, to make clear sense of details. Moreover, five of the consonants used in the English language—b, d, f, r, and v—are absent from almost the entire Salish family of dialects and are freely replaced by the sounds of p, t, l, and m, or were elided. (See Governor Stevens’s recommendation of the guide “Gab[r]iel” to John Mullan.) The nasal French n was also unpronounceable by the Salish.[7]Palladino, Indian and White, 154. George C. Shaw, The Chinook Jargon and How to Use It: A Complete and Exhaustive Lexicon of the Oldest Trade Language of the American Continent (Seattle: Rainer … Continue reading Those anomalies challenged the persons responsible for adding events to the records. Over the mission’s 25-year history, one baptismal name might appear in several different spellings, if uttered by two or more speakers and written down by different scribes, for each of whom both Latin and English were second languages.

Four occurrences of the name Lolo occur in the birth, baptism, confirmation, marriage and burial records of the second St. Mary’s mission. It is always paired with the name Lawrence, and is consistently written Lo Lo or Lolo, with or without an accent over one o or the other; it was never spelled “Lou Lou.”

The earliest reference, entered late in 1868, reads (the parentheses are in the original record): “Lawrence (Lo-Lo) child of Saplie [“son of a certain George”] and Mary; born Dec. 17, 1868; baptised Dec. 19, 1868 at St. Mary’s by Fr. Jos. Giorda.” On September 23 that same year Fr. Giorda entered into the marriage record: “Placid, son of Ben Kaiser and Ann and about 20 years of age, and Adeline, [a] daughter of Lo-Lò, [and] a widow of Maltin.” “Maltin” was perhaps Martin in English. If the bride was also about 20 years old, she could have been a daughter of the Lolo killed by a grizzly in 1850, but we can’t even be certain he had a wife, much less a daughter.[8]Allowing for the Selish need to substitute an l for an r, “Maltin” may have been Emanuel Martin, commonly referred to as “Old Manwell the Spaniard,” a Mexican trapper and … Continue reading

In June 1882, “Lawrence (Lo-Lò) son of Mary,” then 14 years of age, was a witness to the marriage of James de la Wair, widower, and Mary, widow of Michael.[9]James de la Wair was better known around Fort Owen as Delaware Jim, an Iroquois who, with his brother Ben, was among the many men of various tribes—Pend d’Orielles, Spokanes, Nez Perces, … Continue reading The last occurrence of the name Lolo was in a dolorous entry in the baptismal records: “Catherine whose parent was Lawrence (Lolo) was baptized privately by Fr. Joseph Bandini, and died on 13 March 1888.”

Thereafter, until the mission was closed in 1891, five Salish men named Lawrence and two named Laurence—sometimes a male English name; in French, usually a female name—are mentioned in the sacramental registers, but apparently none of them were otherwise known as Lolo.[10]In the Acadian French dialect (along the Mississippi from Louisiana to Missouri), Laurence was the feminine gender of the masculine proper noun Laurent. The English and Italian Lawrence does not … Continue reading

Notes

| ↑1 | Lucylle H. Evans, Good Samaritan of the Northwest: Anthony Ravalli, S.J., 1812-1884, Stevensville: Montana Creative Consultants, 1981), 102. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ralph Space, The Lolo Trail: A History and a Guide to the Trail of Lewis and Clark Second Edition (Missoula, Montana: Historic Montana Publishing, 2001), 8. |

| ↑3 | Gilbert J. Garraghan, S.J., The Jesuits of the Middle United States, 3 vols. (New York: America Press, 1938), 2:386. |

| ↑4 | Lucylle H. Evans, St. Mary’s in the Rocky Mountains: A History of the Cradle of Montana’s Culture (Stevensville, MT: Montana Creative Consultants. 1975), 123. |

| ↑5 | Pierre-Jean De Smet (1801-1873), “Letters and Sketches, 1841-1842”; reprint of original English edition; Philadelphia, 1843; in Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Early Western Travels, 1748-1846, 32 vols. (Cleveland: A. H. Clark Co., 1904), 27:333-34. |

| ↑6 | Robert Bigart, Life and Death at St. Mary’s Mission, Montana: Births, Marriages, Deaths, and Survival among the Bitterroot Salish Indians, 1866-1891 (Pablo, Montana: Salish-Kootenai College Press, 2005). |

| ↑7 | Palladino, Indian and White, 154. George C. Shaw, The Chinook Jargon and How to Use It: A Complete and Exhaustive Lexicon of the Oldest Trade Language of the American Continent (Seattle: Rainer Printing Company, Inc., 1909), p. 9. Internet Archive, 2008. |

| ↑8 | Allowing for the Selish need to substitute an l for an r, “Maltin” may have been Emanuel Martin, commonly referred to as “Old Manwell the Spaniard,” a Mexican trapper and guide who spent most of his life in the northern Rockies. Early in the 1850s he led the first ox-drawn wagons—perhaps Frank Woody’s in 1856—into the Bitterroot Valley from Fort Hall, Idaho, 280 miles to the south. Fort Hall was one of the principal transfer points on the Emigrant Road or Oregon Trail, and thus was a place where former “mountain men” could begin new lives, trading with emigrants. Manwell became a Bitterroot Valley farmer in 1858, and died there in 1873. Weisel, 38. |

| ↑9 | James de la Wair was better known around Fort Owen as Delaware Jim, an Iroquois who, with his brother Ben, was among the many men of various tribes—Pend d’Orielles, Spokanes, Nez Perces, Shawnees, Snakes, and a few from the southwest—who married Salish women that had been widowed by Blackfeet warriors. In 1877, Delaware Jim was an interpreter for the parley at Fort Fizzle between Captain Rawn of the U.S. Infantry and Chief Looking Glass of the non-treaty Nez Perces. Jim lived until 1951. Ibid., 117-19. The spelling of Lo-Lò, with an acute accent over the second o, is difficult to interpret. In George Gibbs’s Trade Jargon dictionary of 1863 (p. 16), the presence of grave accent over the second syllable either changed Lolo from a verb to an adjective meaning “round’ whole’ the entire of anything,” or it indicated emphasis on the accented syllable. |

| ↑10 | In the Acadian French dialect (along the Mississippi from Louisiana to Missouri), Laurence was the feminine gender of the masculine proper noun Laurent. The English and Italian Lawrence does not appear in Acadian. The urban French-Canadian synonym for Lawrence is Leander. American-French Genealogical Society, http://www.afgs.org/ (accessed May 26, 2011). Acadia Genealogical and Historical Society, Ind. and LaGenWeb Acadia Parish Genealogy. |