It’s a safe bet that among the very first words uttered by the earliest humans sometime between 50,000 and 200,000 years ago were angry imprecations directed at the fragile but highly adaptable miniature animals that had held dominion over most of the earth for millions of years before Homo sapiens came to be. It was the miniature creature that has for the past five hundred years, at least in the English-speaking regions of the Western Hemisphere, owned a Spanish name, the diminutive form of the noun musca, now usually spelled mosquito–”little fly”–except in England, where for centuries it has commonly been called a gnat.[1]Owen’s Dictionary, s.v. Culex.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, every traveler whose journey was challenging and extensive enough to justify a travel memoir could scarcely refrain from bringing up the world’s most vexatious, adaptable and–as yet unsuspected by the wisest poets and philosophers–deadly little fly.

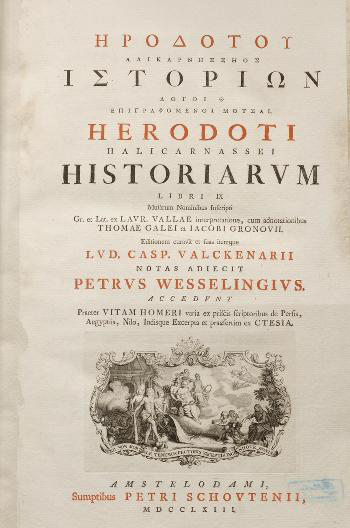

The Greek historian Herodotus (484-425 BC) claimed that there had been so many mosquitoes in the Old Kingdom of Egypt that people who lived near the Nile slept on towers to escape them at night. Experience would have taught them that the species that feed on human blood won’t fly more than 25 feet above their breeding grounds. But that would have been high enough in ancient times to make them capable of disrupting battles, routing armies, and driving both wild and domestic animals to madness. In ancient Mesopotamia it was said that lions, those reputed kings of beasts, sometimes drowned themselves or scratched out their own eyes in frantic efforts to end the torment inflicted on them by hordes of the little bloodsuckers.[2]Leland O. Howard, Harrison G. Dyar, and Frederick Knab, The Mosquitoes of North and Central America and the West Indies, 4 vols. in 3 (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1912), 1:8.

“Murmuring Small Trompets”

There can be hardly a person on earth who has not heard the simple little tune the mosquito croons, con espressivo. Poets and philosophers have meditated on it. The early Roman naturalist Pliny the Younger (ca. 30-ca. 112 AD) complained, “Who gave the mosquito so terrifying a voice, infinitely greater than it should be in comparison to the size of its body?” The English poet Edmund Spenser (1552-1599), in his allegorical ode to Queen Elizabeth I, The Faerie Queene (1596), compared the rascally neighbors who tried to drive two noble, well-intentioned knights away from the castle of “the mighty Queene of Faerie,” with a swarm of noxious mosquitoes:

As when a swarme of Gnats at euentide

Out of the fennes[3]Fennes (fens) are marshes. of Allan do arise,

Their murmuring small trompets sounden wide,

Whiles in the aire their clustring army flies,

That as a cloud doth seeme to dim the skies;

Ne man nor beast may rest, or take repast,

For their sharpe wounds, and noyous iniuries,

Till the fierce Northerne wind with blustring blast

Doth blow them quite away, and in the Ocean cast.[4]The Faerie Queene, from The Complete Works in Verse and Prose of Edmund Spenser, Prepared by Risa Bear (London: Grosart, 1882), Book II, Canto ix, 16. HTML EText, … Continue reading

Spenser also translated a rhymed stanzaic paraphrase of Culex (“The Mosquito”) a story once attributed to the Greek poet Virgil (70 BC–90 BC). It tells of a shepherd who, having fallen asleep, was about to be attacked by a snake when a gnat–that is, a mosquito–wakened him by biting him on an eyelid. The shepherd killed the gnat and then dispatched the snake. On the following night the shepherd dreamed that the gnat’s ghost scolded him for his ingratitude. For penance the shepherd erected a monument to his diminutive savior.[5]http://www.mysteriesofcanada.com/Manitoba/mosquito_capital_of_canada.htm. (accessed 14 July 2008).

Thoreau’s Tribute

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862), the American author, poet, naturalist and transcendentalist philosopher, conceived a kinder, nobler tribute to the mosquito.

Mornings bring back the heroic ages. I was as much affected by the faint hum of a mosquito making its invisible and unimaginable tour through my apartment at earliest dawn, when I was sitting with the door and windows open, as I could be by any trumpet that ever sang of fame. It was Homer’s requiem; itself an Iliad and Odyssey in the air, singing its own wrath and wanderings. There was something cosmical about it; a standing advertisement, till forbidden, of the everlasting vigor and fertility of the world.[6]Walden (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1912), 115.

Lewis’s climactic pronouncement on the species was as close as he came to fellowship in the leagues of philosophers and poets. He compared the mosquito to the worst of the plagues Jaweh used in his war of attrition against Egypt’s Pharoah.

Notes

| ↑1 | Owen’s Dictionary, s.v. Culex. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Leland O. Howard, Harrison G. Dyar, and Frederick Knab, The Mosquitoes of North and Central America and the West Indies, 4 vols. in 3 (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1912), 1:8. |

| ↑3 | Fennes (fens) are marshes. |

| ↑4 | The Faerie Queene, from The Complete Works in Verse and Prose of Edmund Spenser, Prepared by Risa Bear (London: Grosart, 1882), Book II, Canto ix, 16. HTML EText, http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~rbear/queene2.html (accessed 14 July 2008). |

| ↑5 | http://www.mysteriesofcanada.com/Manitoba/mosquito_capital_of_canada.htm. (accessed 14 July 2008). |

| ↑6 | Walden (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1912), 115. |