David Douglas, now a skilled geographer, and surveyor George Barnston repeated observations taken by the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805 and by David Thompson in 1811.

Much as Meriwether Lewis did prior to his expedition, Douglas learned to calculate latitude and longitude by using a mariner’s sextant.

Sabine’s Tutelage

At the beginning of Douglas’s stint in London, he was received with remarkable acclaim for the relatively unschooled son of a village mason. Yet he soon chafed at the restrictions of what was at that time a very strict class society, and focused instead on expanding the scope his work. The writings of Alexander Mackenzie, George Vancouver, and Lewis and Clark, combined with the memories of cartographer David Thompson‘s crew, provided Douglas with a deep appreciation for the role that careful surveys had played in these explorer’s accomplishments. To match them would require that he learn some basic skills, and in London, quite by chance, he found a willing teacher.

Edward Sabine, the younger brother of Douglas’s boss at the Horticultural Society, had served as an officer in the Royal Navy during the War of 1812 before turning his attention to the study of physical geography and the properties of terrestrial magnetism. As astronomer on Captain John Ross’s first Arctic expedition in 1819, Sabine developed a particular interest in the problems of finding magnetic north.

David Douglas shared lodgings with Sabine during his stay in London, and in 1828 began assisting him in his geomagnetic measurements. When the naturalist secured approval for a second collecting trip to the Northwest, he reached out to Sabine for some practical advice. “While preparing for his departure in the summer of 1829, I heard [Douglas] frequently express his regret that his limited education prevented his being able to render those services to the geographical and physical sciences,” Sabine later wrote. “He spoke with particular regret of his inability to fix geographical positions.”[1]Edward Sabine, “Notes on the geographical observations made by David Douglas on the Pacific Coast of North America.” MS-0623 (1837), 2. Archives of British Columbia, Victoria.

Recognizing Douglas’s combination of boundless physical energy with “vigor of mind,”[2]Ibid., 6. Sabine offered to serve as his friend’s tutor during the three months that remained before his scheduled departure. At the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, the two fell into a regime that echoed Thomas Jefferson‘s concentrated training of Meriwether Lewis at Monticello. Based on his own practical experience, Sabine had a sense of how to feed his pupil “just so much knowledge of plane and spherical trigonometry, and of the nature and use of logarithms, as was essential for his practical purposes. . . . For eighteen hours a day he bent all the powers of his mind to overcome difficulties, for which his previous education and habits had so little prepared him.”[3]Sabine, “Notes,” 6.

Study in Earth’s Magnetism

“Apparatus for Dip and Intensity and variation of the Magnetic needle have been given to me in the most handsome manner from the Colonial Office.”[4]Douglas to William Jackson Hooker, 27 October 1829. Papers. Lindley Library, Royal Horticultural Society, London.

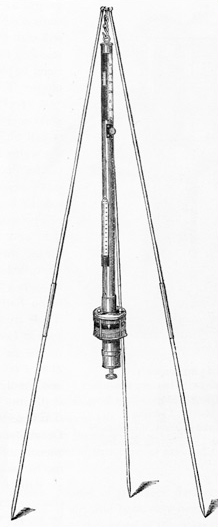

Because of Sabine’s deep interest in the earth’s magnetic properties, Douglas received a very individual mode of astronomical instruction. The captain demonstrated how iron bars suspended from a tripod allowed an observer to measure “the relative intensity of magnetic attraction in different parts of the earth’s surface.”[5]Ibid., 4. He acquainted Douglas with the use of the dip circle (fig. 3), a compass supported on gimbals that pivots on a plane to reveal the angle the magnetic field makes with the vertical. He also taught Douglas how to hang a magnetically charged needle from a tripod, then watch as Earth’s magnetism made that needle vibrate. In London, such a needle suspended from a tripod on asbestos thread twitched exactly one hundred times in three hundred seconds. By measuring slight differences in the frequency of those vibrations at other locations around the world, Sabine had begun to describe sweeping “isographic” curves that covered the earth in exactly the same way “that iron filings arrange themselves around a magnetized iron sphere.”[6]Edward Sabine, “Observations on the Magnetism of the Earth . . . ,” American Journal of Science and Art, vol. 17 (1830): 146.

Sabine combined these experiments in magnetism with a thorough knowledge of standard nautical measurements, including the use of accurate temperature and dew point readings to determine elevation, as well as the intricate trigonometry necessary to calculate latitude and longitude. In addition to the mariner’s sextant (fig. 1), Sabine taught Douglas to use a repeating reflecting circle—a larger, heavier instrument that contained two reflecting mirrors and a full circle rather than sixty degrees of arc. The teacher soon felt confident that with a few weeks of steady instruction, combined with the better part of a year to practice on the outbound ship, his pupil would be fully competent “to undertake a variety of determinations which might render his mission important to other branches of science besides those of natural history.”[7]Ibid., 147.

Shopping at Dollond and Sons

With a Pacific Northwest boundary settlement between British Canada and the United States pending, the Colonial Office in London took an interest in Douglas’s newly acquired skills, and supplied him with a stipend to acquire both surveying manuals and a full set of secondhand but serviceable equipment. Edward Sabine, with a more sophisticated set of tools in mind, took Douglas to the shop of Dollond and Sons, the family that had supplied instruments to both Thomas Jefferson and David Thompson. Douglas’s final list included not only both a quality sextant and repeating reflecting circle, but also a Dollond compass, dip needles, and dip circle; a tripod, magnetic bars, and the special asbestos thread to hang them on; two state-of-the-art chronometers; plus a thermometer, barometer, hydrometer, and hygrometer. The entire package weighed enough that in the field Douglas required an extra man to carry his equipment, and the competent use of such instruments would prove a daunting task for a novice. But then, his teacher had very lofty goals in mind.

Surveying the American West

Alexander von Humboldt had recorded anomalies in the earth’s magnetic fields during his South American expedition of 1799-1804. Soon after his return to Germany, he had published a paper that, drawing on the work of astronomer Edmond Halley, introduced the notion of a map that described these fluctuations with parallel “isolines.” Over the next few years, Humboldt developed a plan to employ scientists worldwide to collect the data necessary to chart them on a global map. By 1829, Edward Sabine was coordinating Humboldt’s project from the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. He assigned David Douglas to cover a significant portion of North America, and expected the naturalist to make a very real contribution to the undertaking.

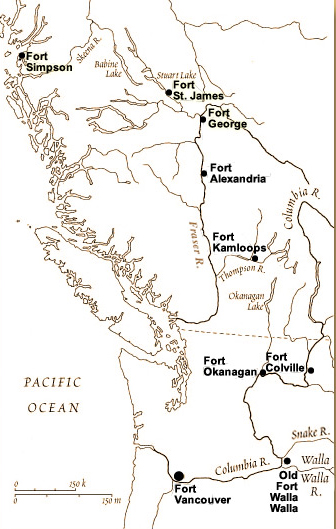

As David Douglas progressed around Cape Horn on his 1829-30 voyage to the Columbia River, he diligently practiced with the tools of his new trade. When he arrived at Fort Vancouver in June 1830, Hudson’s Bay Company clerk and trained surveyor George Barnston described with great delight the careful unpacking of his friend’s new tool kit. Barnston appreciated Douglas’s meticulous recalibration and trial of each device as the former plant collector demonstrated his mastery over the full range of his new discipline. “His astronomical work advanced surely and rapidly. The regularity of barometrical and magnetical figurings was conspicuous, and the diurnal variations of temperature remarkably equal, the humidity of the atmosphere generally a mere trifle,”[8]George Barnston, “Abridged Sketch of the Life of Mr. David Douglas, Botanist, with a Few Details of His Travels and Discoveries,” Canadian Naturalist and Geologist, 5 (1860), 268. Barnston wrote. The clerk was equally impressed with his friend’s diligence as he calculated shot after shot for longitude, using two different methods of the time, to determine the exact position of Fort Vancouver. These coordinates would serve as his benchmark for future observations.

Traveling upstream to Fort Walla Walla, Barnston assisted Douglas in surveys at the confluence of the Snake and Columbia Rivers, a place of great importance to any British claims for the proposed international boundary settlement. As they set up their instruments, the pair would have been well aware that they were repeating observations taken by the Corps of Discovery in 1805 and by David Thompson in 1811. While Thompson, the Hudson’s Bay Company, and stalwarts of the British Empire assumed that this shot would represent the boundary between American and British territory, the vision of Thomas Jefferson disagreed.

Edward Sabine had hoped that Douglas would be able to next move south from the Columbia River, taking magnetic observations along overland fur trade routes through Oregon and into California. When a malaria epidemic coupled with an erosion of tribal relationships made for dangerous traveling, Douglas decided to sail to Spanish territory instead. Based in Monterey, he spent the next two years working in California. There he often stayed at Franciscan missions on the Camino Real, and although his personal journal for that time is lost, the survey notebooks he sent back to Sabine display a list of coordinates stretching north to Santa Rosa and south to Santa Barbara.

New Caladonia Adventures

When he returned to Fort Vancouver from California in the spring of 1833, Douglas had his sights set on a northerly excursion that combined several of his stated goals in the realms of surveying, geography, and comparative botany. Russian naval officer Fyodor Litke, one of von Humboldt and Edward Sabine’s many associates, had encouraged Douglas to think about returning to London via the North Pacific and Siberia; Baron von Wrangel, chief officer of the Russia-America Fur Trade Company, offered the naturalist secure quarters in Alaska and free passage to the Russian mainland.

Traveling with a fur trade brigade north from Fort Okanogan to Fort Kamloops, then west to the Fraser River, Douglas arrived at Fort Alexandria in early May. This was the place where in 1793 another of his heroes, Sir Alexander Mackenzie, had broken off from that wild river to follow a tribal trail to the Pacific, and Douglas worked hard to determine an accurate latitude and longitude of the place. While at Fort Alexandria, he also spent an entire night observing how a particularly intense burst of aurora borealis affected his magnetic bars.

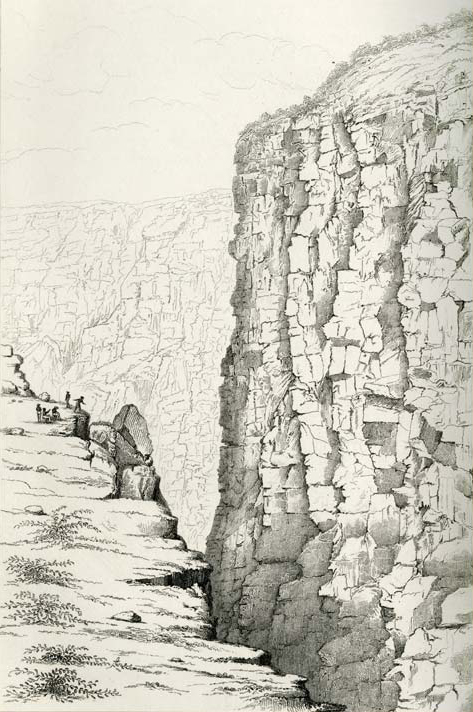

Douglas continued north as far as Fort Saint James, but rather than attempt an overland trek to a Russian fur outpost on the coast, he decided to return south via canoe. A canoe accident in Fort George Canyon on the Fraser River carried off his personal journal and plant specimens, but Douglas did manage to rescue his surveying instruments and astronomical calculations. One of those notebooks contained a set of sketch maps depicting his route from Fort Okanogan to the junction of the Fraser and Quesnel Rivers, as well as a series of coordinates attached to landmarks that extended further north. His latitudes and longitudes represented the most accurate positions taken up to that time for the region.

After canoeing back to Fort Vancouver, Douglas dropped his plans for a Siberean excursion and sailed instead for Hawaii, where he focused the entire range of his skills on the volcanic landscape of the Big Island. Guided by a Hawaiian named John Honorii, he ascended first Mauna Loa and then Mauna Kea. From their summits, he recorded a series of barometric readings and coordinates. Douglas was then able to calculate the first accurate altitudes for these peaks by comparing his data with coordinated measurements taken at sea level by an American missionary.

Hawaiian Conclusion

“One day there madam” [at Kilauea Crater], “is worth one year of common existence.”[9]Douglas, letter to Mrs. Richard Charlton. Hawaiian Spectator, April 1839, 100-101.

Douglas and his missionary friends had been greatly excited by the publication of Charles Lyell’s Elements of Geology, which provided a basis for understanding many of the elemental earth-building processes. Addressing the subject in a letter, Douglas echoed Alexander von Humboldt’s grand ideas when he described his studies at the active Kileuea Crater as a synthesis of his botanical, surveying, and geological pursuits: “All will be reconciled, and we shall see no longer as ‘through a glass, darkly,’ the infinitude, the beauty, the harmony of nature. I must return to the volcano, if it is only to look—to look, and admire.”[10]Ibid.

In his last report to Captain Sabine, in May 1834, Douglas wrote that although he intended to return to England at the first opportunity, he was far from being finished with his work. “I shall continue to labour at these islands,” he promised, “to the best of my ability.”[11]“Extract from a Private Letter addressed to Captain Sabine, R.A., F.R.S., by Mr. David Douglas, F.L.S. Dated Woahoo (Sandwich Islands), 3d of May, 1834. in Journal of the Royal Geographical … Continue reading In fact, he carried on his surveying and plant-hunting until he perished in a cattle pit trap on the Big Island that July, at age 35. The missionaries he worked with transferred Douglas’s survey books to the British envoy in Honolulu, who in turn shipped them back to England. There his data contributed to pioneering work on geomagnetism that Edward Sabine published over the next several years.

Notes

| ↑1 | Edward Sabine, “Notes on the geographical observations made by David Douglas on the Pacific Coast of North America.” MS-0623 (1837), 2. Archives of British Columbia, Victoria. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ibid., 6. |

| ↑3 | Sabine, “Notes,” 6. |

| ↑4 | Douglas to William Jackson Hooker, 27 October 1829. Papers. Lindley Library, Royal Horticultural Society, London. |

| ↑5 | Ibid., 4. |

| ↑6 | Edward Sabine, “Observations on the Magnetism of the Earth . . . ,” American Journal of Science and Art, vol. 17 (1830): 146. |

| ↑7 | Ibid., 147. |

| ↑8 | George Barnston, “Abridged Sketch of the Life of Mr. David Douglas, Botanist, with a Few Details of His Travels and Discoveries,” Canadian Naturalist and Geologist, 5 (1860), 268. |

| ↑9 | Douglas, letter to Mrs. Richard Charlton. Hawaiian Spectator, April 1839, 100-101. |

| ↑10 | Ibid. |

| ↑11 | “Extract from a Private Letter addressed to Captain Sabine, R.A., F.R.S., by Mr. David Douglas, F.L.S. Dated Woahoo (Sandwich Islands), 3d of May, 1834. in Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, vol. 4 (1834): 342. |