Starting at Celilo Falls and continuing to the Pacific, they passed through flea country. Even today, the insects can wreak havoc there, especially in the fall.

the Flea, though hee kill none,

hee does all the harme hee can.

Portaging the Falls of the Columbia

For a fuller analysis of this and Clark’s 1814 map of the same area, see on this site Clark’s Columbia River Maps. See also Celilo Falls.

The day, 23 October 1805, was a day to remember. To begin with, Captain Lewis walked to some nearby Indian lodges where he and his co-captain had seen a couple of Indian canoes that they had immediately taken a liking to. Those canoes were “neeter made” than any they had ever seen. Clearly they were “calculated to ride the waves,” and best of all, they were “dug thin.” Lewis successfully bargained for one of them, offering the Corps’ “Smallest Canoe” plus “a Hatchet & few trinkets” as payment. It was possibly the best deal of the whole trip to date. Regrettably, we will never know what the native dealer saw in their scout canoe that made it more valuable than his own “neeter” one. The man claimed to have bought it for the price of a horse from a white man somewhere downriver—presumably a seasonal European or American fur trader.

As to the rest of the Corps, every man had urgent work to do, and the curious spectators who crowded the narrow trail along the riverbank were about all the distractions they could tolerate. Captain Clark supervised the process of getting their dugout canoes across the river above the 37′ 8″ pitch of the “grand falls of the Columbia,” and dragging them down a steep and rocky ¾-mile trail (see Clark’s Columbia Maps), and then, having put them back in the raging torrent, easing them gingerly over an 8-foot pitch with the ropes they had braided from strips of elk skin. Shortly, two comparatively insignificant three-foot falls delivered another breath-sucking crisis. This time the belay rope broke, and the unmanned canoe it was tied to would have been permanently lost to them but for quick action by some Indian bystanders down below—to whom, naturally, the captains had to pay a gratuity.

One reason that fleas generally prefer rodent hosts over human hosts, is that the maximum vertical height reached by a Pulex irritans is 19.7 cm (7.75 in). They possess appropriate claws that enable them to run up a person’s leg or a rodent’s body.[2]Imms’ General Textbook of Entomology This photograph shows how the corpsmen’ legs may have looked before they stripped themselves down to enable them to brush the fleas from their legs—while carrying heavy weights on their shoulders.

Flea bites sometimes occur in groups of three, in more or less symmetrical arrangement. One such group in the above photo is the three equidistant wounds of a similar shade of red—facetiously referred to as ”breakfast, lunch, and dinner.” It has been said that it can take as much as one hour for a flea to engorge itself on a blood meal.

Meanwhile, all the baggage and equipment in their six canoes had to be portaged “over bad ground” before dark that same day. “So,” reported Private Whitehouse, “we went to carrying the baggage by land on our backs,” and also “hired a fiew horse loads by the natives.” To top off their day, one of the two Nez Perce chiefs who had accompanied them as guides and interpreters for more than two weeks since departing their Canoe Camp on the Clearwater River, told the captains they had overheard some Indians downstream boast that they were going to kill the approaching strangers. The explorers couldn’t have been seriously concerned, of course. After all, they were American soldiers whose fathers and older brothers had just fought and won a long war against forces of superior number, training, discipline and armament to gain political and cultural Independence for their new nation. They could take care of themselves. Still, the rumor was something to keep in mind, so the officers topped off their men’s personal supplies of ammunition at 100 balls each. Just in case. Fortunately, the threat didn’t materialize.

Their rigorous, sustained manual labor on a treacherous trail would have been enough of a challenge, but aside from the press of curious oglers, there was something else that they could not have foreseen, and weren’t prepared to deal with, even though it was by no means unfamiliar. One and all certainly recognized it, but they hadn’t encountered any since the beginning of the expedition, or if they had, not in sufficient numbers to make it worth mentioning. Clark recorded it in his daily journal, and Nicholas Biddle rephrased it in the captain’s behalf—in his own way:

About three o’clock we reached the lower camp, but our joy at having accomplished this object was somewhat diminished by the persecution of a new acquaintance. On reaching the upper point of the portage [3]On the south bank of the river at the head of the Great Falls of the Columbia (in today’s Wasco County, Oregon), was a Wasco Indian village. Opposite, on the north bank of the river (in … Continue reading we found that the Indians had camped there not long since, and had left behind them multitudes of fleas. These sagacious animals were so pleased to exchange the straw and fish-skins, in which they had been living, for some better residence, that we were soon covered with them, and during the portage the men were obliged to strip to the skin in order to brush them from their bodies.[4]History of the Expedition under the command of Captains Lewis and Clark, to the sources of the Missouri, thence across the Rocky Mountains and down the River Columbia to the Pacific Ocean: Performed … Continue reading

Clark himself didn’t minced words: “every man of the party was obliged to Strip naked during the time of takeing over the canoes [and their baggage], that they might have an oppertunity of brushing the flees”—he always spelled it phonetically, with a double-e—”of[f] their legs and bodies.” It must have been quite a sight.

And that was only the beginning of their encounter.

Lower Columbia Pests

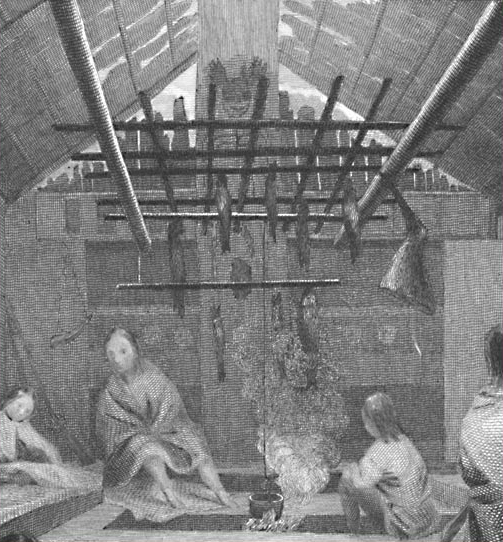

Detail from “Interior of a Chinook House”

by Alfred T. Agate (1812–1846)

Archives and Special Collections, Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library, University of Montana

Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition (6 vols, 1844-45), Vol. 4, p. 341

For a description of this illustration, artist, and his methods, see Chinookan Houses.

On the 26 October 1805 Clark complained that the fleas were “very troublesome,” and that “with every exertion the men Can’t get rid of them, perticilarly as they have no clothes to change [with] those which they wore.” Four days later and a mile below the beginning of the “great Shute” of the Cascades (also known as the Cascades of the Columbia), he observed a village of “verry large houses built in a different form from any I had Seen, and laterly abandoned, and the most of the boads” had been put into a nearby pond. He supposed it was “to drown the flees, which was emencely noumerous about the houses.”

November 6th dawned cold and wet for the second day in a row. About midday they came upon an “old Village” on the starboard side, and soon another in a “butifull open and extensive bottom” on the larboard side, but both were devoid of all inhabitants “except Two Small dogs nearly Starved, and an unreasonable portion of flees—.” Later that day they landed at a place where, by moving the larger stones, they “made a place Sufficently large for the party to lie leavil on the Smaller Stones Clear of the Tide,” and no doubt clear of fleas, except those traveling with them. The men were “all wet and disagreeable,” but at least there was fuel nearby for large fires over which they could dry their bedding and kill the fleas which had collected in their blankets at every “old village” they encamped near. On the 8th, still “all wet and disagreeable,” they stopped for “dinner” at midday on the west side of Gray’s Bay near another abandoned village, where they found great numbers of flees, which they “treated with the greatest caution and distance.”

The rain that had begun on November 5th continued around the clock for eleven consecutive days, with occasional let-ups of two hours, at most. For the last five of those days the Corps was pinned down on the upriver side of “the blustering Point,” or “Point Distress.”[5]In 1825 it was given the name by which it is still known, Point Ellice, after a Director of the Hudson’s Bay Company, Edward Ellice—pronounced as if spelled Ellis—(1783–1863). At last, in the midafternoon of the 15th “the wind luled, and the river became calm.” That allowed the entire company to double (i.e. navigate around) the point into Vancouver’s Baker Bay (Clark’s “Haley’s”) in their canoes—presumably minus the one that on the 14th had been “much broken by the waves dashing it against the rocks.” They “came to” on a “butifull Sand beech” near a small stream, and a “Small marshey bottom” that offered a suitable campsite on a high spot. Beyond the stream there stood a conspicuous example of a new version of an age-old story: “a large village of 36 houses deserted by the Inds. & in full possession of the flees.”

It’s worth taking time to renew our own acquaintance with the flea.

Fort Clatsop Fleas

At Fort Clatsop on 2 January 1806, Lewis wrote, “we are infested with swarms of flees already in our new habitations; the presumption is therefore strong that we shall not devest ourselves of this intolerably troublesome vermin during our residence here.” There were only three more journalists’ references to fleas until 2 April 1806. Except for Clark’s casual visit to a house in a little village south of Tillamook Head on 9 January 1806, where he observed the occupants were “pore Durty and their house Sworming with flees.” Then no more complaints until 2 April, when they discovered the mouth of the “Multnomah”—now Willamette—River that they had missed the previous October because they passed it on the north side of two overlapping islands which hid it from their mid-river view. Clark took a small party of six enlisted men plus York and an Indian guide, and made a reconnaissance trip ten miles upriver. Their bivouac that night was near a large vacant Indian house where, as Clark found, the fleas were so numerous that they dared not try to sleep in it. Two weeks later, on 15 April 1806, Sergeant Gass had the very last word in the whole episode. The captain and his party “passed a place where there was a village in good order last fall . . . but has been lately torn down, and again erected at a short distance from . . . where it formerly stood. The reason of this removal I cannot conjecture, unless to avoid the fleas which are more numerous in this country than any insects I ever saw” (emphasis added).

How is the sudden onset of the long period of relief from fleas to be explained? The cold wave that blew in on 25 January 1806 and lasted for two weeks may have been part of the answer. In warmer weather before and after that, the captains’ may have relied on the time-honored principle, cleanliness. In any case, until the expedition ended at St. Louis five months later, there was not another complaint about fleas or lice.

Notes

| ↑1 | John Donne, Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions, “Meditations upon our Humane Condition,” XII; (1623). Project Gutenberg, p. 79. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Imms’ General Textbook of Entomology |

| ↑3 | On the south bank of the river at the head of the Great Falls of the Columbia (in today’s Wasco County, Oregon), was a Wasco Indian village. Opposite, on the north bank of the river (in Klickitat County, Washington) was a village of Wishram Indians. Both spoke the same dialect of the Chinookan language family, the basic form of which the Corps would hear from the Chinook tribe on the north side of the estuary, and the Clatsop tribe on the south side near Fort Clatsop. Soon after the Corps reached the head of the falls their two Nez Perce guides left them because they couldn’t understand the Chinookan speakers. |

| ↑4 | History of the Expedition under the command of Captains Lewis and Clark, to the sources of the Missouri, thence across the Rocky Mountains and down the River Columbia to the Pacific Ocean: Performed during the years 1804–5–6. By order of the Government of the United States. Prepared for the press by Paul Allen, Esquire. Two volumes. (Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep, 1814), 2:34–35. |

| ↑5 | In 1825 it was given the name by which it is still known, Point Ellice, after a Director of the Hudson’s Bay Company, Edward Ellice—pronounced as if spelled Ellis—(1783–1863). |