Among the trees opposite the Lewis and Clark River‘s sharp bend at left center, they began building their log huts on 10 December 1805 and moved in–Fleas and all–on Christmas Eve. Today a reconstruction of Fort Clatsop stands at the original site–sans those historic fleas.

It was the end of the road. The Corps of Volunteers for North Western Discovery had fulfilled the principal objective that President Thomas Jefferson had laid before Captain Lewis: “to explore the Missouri river, & such principal stream of it, as, by it’s course and communication with the waters of the Pacific ocean . . . may offer the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent for the purposes of commerce.” On the surprisingly “Clear and butifull” morning of 16 November 1805, they stood on a summit at Cape Disappointment, absorbed by the awesome view of the Columbia River’s meeting with the not-always-pacific western ocean. By Clark’s estimate they had traveled in boats and on horseback 4132 miles from the mouth of the Missouri River.[1]The quotation from “Jefferson’s Instructions to Lewis” is in Jackson, Letters, 1:61. The total mileage figure is from the “Fort Clatsop Miscellany,” Moulton, Journals, … Continue reading But that wasn’t the end of the story. The two officers and their retinue had much to learn about living on the North Western edge of the continent.

Lewis Searches

The scene above was photographed from near the top of the rise where the original garrison is believed to have stood. It shows what is at least the third general forest regrowth after successive clearings for farming and commercial operations such as logging and brick making, which were established there and successively declined during the generations since Lewis and Clark wintered there. Those disturbances, combined with the processes of natural decay and rejuvenation that are accelerated by the perennially moist and temperate coastal climate, left little or no material evidence of the original structure’s existence. Furthermore, the anecdotal evidence gathered from personal recollections, often secondhand at best, and sometimes conflicting, have been of limited help in answering the question. All of this has made precise archaeological identification of the original fort’s location highly unlikely. Nevertheless, the placement of the garrison’s present replica is believed to be “on or near” the site of the original fort.[2]Julie K. Stein and others, “A Geo-archeological Analysis of Fort Clatsop, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park,” University of Washington Department of Anthropology, November 2006. … Continue reading

On 5 December 1805, Captain Lewis, pushing ahead with several enlisted men as aides, finally found a suitable site for the Corps of Discovery’s winter encampment. The main attraction of the place was that several of the Corps’ hunters had seen great numbers of elk thereabouts, an advantage that would too soon introduce them all to a major course of study: how to keep their fresh meat from spoiling. Also, the site was on the south side of the Columbia River estuary a short distance north of the mouth of the Netul River, from which they figured they would be able to see any traders’ ships that crossed the bar as spring approached. They were seriously in need of more trade goods with which to purchase necessities from natives to support their long journey home.[3]They missed by only a few days seeing the first trading vessel enter the estuary for the 1806 season of commerce with the native people. Finally, it was fifteen miles—a little less than a day’s brisk walk—from the ocean where they could boil seawater to make salt.

Later that day Lewis hurried back up the estuary to Point William (today’s Tongue Point) where Clark and the main party were anxiously awaiting him. “A 1000 conjectures has crouded into my mind,” muttered the Kentuckian, “respecting his probable Situation & Safety.” The next day, high winds and waves kept them all from moving downriver, but the 7th dawned under a fair sky, so they started early and breasted the incoming tide for the nine miles down to “Meriwethers Bay”[4]Clark called it “Meriwethers Bay” in the mistaken belief that Lewis was the first white man ever to see it. In fact, the first was Lieutenant William Robert Broughton, of Captain George … Continue reading as fast as they could paddle, and set up a temporary bivouac “in a thick groth of pine[5]Well into the early 19th century in England and the U.S., naturalists persisted in referring to all evergreen conifers informally as “pines.” about 200 yards from the river . . . on a rise about 30 feet higher than the high tides.” Clark approved. This, he agreed, was “certainly the most eligable Situation for our purposes of any in its neighbourhood.” Best of all, there was a freshwater spring near the place where the rear exit of the parade enclosure would be. That exit was called—what else?—the “water gate.”

Clearing the Space

Undoubtedly the captains had observed that in the moist climate west of the Cascades, woods and undergrowth often covered the land to the river’s edge, and had discussed the slim prospects of finding a suitable place for what they needed to build. They had sketched out a plan for their fort, but it seemed that finding a level spot at least fifty feet square would be next to impossible. But after days of deliberate searching, a potential site was located.

Then the real labor had to begin without delay. First, there was the felling and limbing of trees that could be used for the walls of the structure. The useable logs had to be cut to length and stacked into “decks” handy to the site’s boundaries. Trees that were too small or too large for building had to be bucked up and split into firewood, then stacked in orderly ranks and somehow sheltered from the daily and nightly showers until they were dry enough to burn. Finally, all of the litter from those initial steps, plus the non-woody undergrowth such as the superabundant ferns, had to be cut and carried away from the structure’s eventual site before construction could begin.

Floor Plans

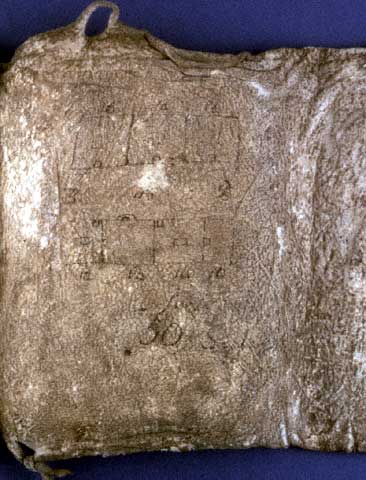

Floor Plan of Fort Clatsop

Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis.

Exactly how their winter cantonement of 1803-04, called Camp Dubois, was laid out, is unknown. The captains left no sketch of a floor plan, so replication had to be based on verbal clues in the journals and examples of earlier fortifications along the Mississippi.[6]See photographs of a logical solution at the Lewis & Clark State Historic Site near Hartford, Illinois (http://www.campdubois.com/html/winter_camp.html). We do know, however, that the 1804-05 winter camp, Fort Mandan, was built over a triangle, and that the floor plan of Fort Clatsop was a square. Clark and his men apparently cobbled together the huts comprising Camp Dubois in about 18 days, whereas they spent 54 days building Fort Mandan, partly because of the need to create the next best thing to a Mandan earth lodge, partly to shelter themselves against what has long since been politely referred to as a “North Dakota Winter,” and partly out of an apparent need for battle readiness to repel assaults by Sioux and Arikara warriors. But here, on the south side of the Columbia River estuary, seven overland miles from the Pacific Ocean, where they were to wait out the winter of 1805-06, they consumed 22 workdays just sheltering themselves from the persistent rain, and coping with a number of new and unforeseen challenges. Discoveries, if you will.

Notes

| ↑1 | The quotation from “Jefferson’s Instructions to Lewis” is in Jackson, Letters, 1:61. The total mileage figure is from the “Fort Clatsop Miscellany,” Moulton, Journals, 6:458. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Julie K. Stein and others, “A Geo-archeological Analysis of Fort Clatsop, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park,” University of Washington Department of Anthropology, November 2006. http://www.nps.gov/lewi/historyculture/upload/UW_Geoarch_Report_2006.pdf (retrieved 5 October 2013). |

| ↑3 | They missed by only a few days seeing the first trading vessel enter the estuary for the 1806 season of commerce with the native people. |

| ↑4 | Clark called it “Meriwethers Bay” in the mistaken belief that Lewis was the first white man ever to see it. In fact, the first was Lieutenant William Robert Broughton, of Captain George Vancouver’s expedition, who in May 1792 named the principal river that feeds it Young’s River, in honor of his uncle, Admiral Sir George Young of the Royal Navy. The other river that empties into the bay is the Netul–accent on the second syllable, /nit’ul/–which was renamed “Lewis and Clark River” in 1925. |

| ↑5 | Well into the early 19th century in England and the U.S., naturalists persisted in referring to all evergreen conifers informally as “pines.” |

| ↑6 | See photographs of a logical solution at the Lewis & Clark State Historic Site near Hartford, Illinois (http://www.campdubois.com/html/winter_camp.html). |