Runaway Growth

In January 1803, President Jefferson assured Congress that an overland expedition to the Pacific could be pulled off by “an intelligent officer with ten or twelve chosen men.”

Yet when that expedition left its North Dakota winter quarters in April 1805, it was led by two officers, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. Their whole party numbered 33 people, more than double the force originally planned. And that was the “permanent” corps of explorers that actually went to the Pacific: there had been 45 or more travelers on the journey’s first leg from St. Louis.

The story of the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s seemingly runaway growth is a hard one to piece together. The leading participants didn’t say much about it on the record that has survived. The main unanswered question is whether anyone in Washington authorized the expansion or, as seems quite likely, the leaders did it on their own without much fear of official censure if they returned in triumph.

An Improvised Plan

What clearly comes through any close examination of how, when and why the Expedition ballooned in size is a sense of improvisation: the numbers changed as the magnitude of the effort gradually became apparent. And that, in turn, required more improvisation, such as a scramble for extra supplies for the extra people.

Picking the right number of explorers was a matter of cut-and-dry, because there were no rules stating how big a North American wilderness expedition should be. Early ideas for exploring the West were colored by the colonial practice of sneaking small groups past hostile Indians in the Eastern woodlands. When Congressman Jefferson, in 1783, sounded out George Rogers Clark on leading a California expedition, the Revolutionary War hero cautioned against “large parties” that would “alarm the Indian Nations they pass through.” Three or four young men would be enough, the General thought.[2]Jackson, Donald, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. (University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 1978), 2:656.

Plan A: The Cumberland River

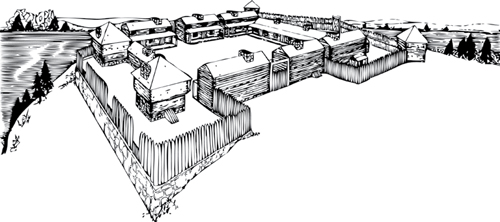

For more, see Fort Southwest Point.

What seems to have attracted later imitators was Alexander Mackenzie‘s brilliantly successful 1793 dash to the Pacific across Canada’s Rockies. Including Mackenzie, that party numbered 10 lightly armed civilians. Mackenzie’s 1801 account of this adventure did more than stir President Jefferson into launching his own Pacific expedition. Lewis and Jefferson also used Mackenzie’s detailed journal as a “handbook” for planning the size and equipage of the American exploring party, according to persuasive speculation by David Freeman Hawke in Those Tremendous Mountains, a nonfiction account of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.[3]Hawke, David Freeman, Those Tremendous Mountains. (W.W. Norton, N.Y., 1985 paperback ed.), 11.

An American force of an officer and 10 or 12 soldiers was the understanding on which Congress voted the expedition’s initial $2,500 appropriation on 22 February 1803. A week later Jefferson began informing his scientific friends in Philadelphia that Lewis, designated to lead “a party of about ten” to the West, would soon be calling on them for advice. As late as 20 June, Jefferson’s formal instructions to Lewis placed the number of “attendants” at 10 to 12.

In fact, however, the roster was already creeping higher. Lewis was authorized to recruit another office as his backup. Lewis spent all of April and May in Harpers Ferry and Philadelphia, acquiring enough supplies to equip a party of 15. He obtained 15 new Army rifles from the Harpers Ferry arsenal, 15 powder horns from the Army depot in Philadelphia, 15 blankets, 15 scalping knives, 15 knapsacks.

His original plan was to commandeer a core group of soldier explorers from the Army post at South West Point, near present Kingston in east Tennessee, and march them to Nashville. There, Lewis and the soldiers would pick up a previously ordered military barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) and large canoe and float them down the Cumberland River to its junction with the Ohio.

Plan B: The Ohio River

But toward the end of his stay in Philadelphia, Lewis had to junk this plan and improvise a new one. He learned there were too few good men at South West Point, and that no boat would be waiting in Nashville. So from Philadelphia he sent specifications to a boat builder in Pittsburgh for another custom-made vessel. No longer counting on an initial force of soldiers from Tennessee, Lewis asked the Army to send some substitutes to Pittsburgh just to help him take his new barge directly down the Ohio River later that summer.

For the first time Lewis was dividing his manpower needs into two categories: a “permanent” party of subordinates who would go with him all the way to the Pacific, and temporary groups of people who would do specific jobs and then peel away. The eight men sent by the Army to Pittsburgh were new recruits awaiting transfer to Fort Adams in Mississippi Territory; after taking Lewis’s boat nearly to the mouth of the Ohio, they would go on to their new post.

Setting the Stage

Lewis returned to Washington on 17 June 1803 and plunged into a final round of planning with Jefferson and Secretary of War Henry Dearborn. There was an exciting new development: word from Ambassador Robert Livingston in Paris that Napoleon wanted to sell the whole of Louisiana to the United States. If the deal materialized the explorers would be exploring their own territory, with less worry about European sensitivities. there would be no diplomatic need to skimp on manpower during the first season’s travel up the Missouri. Dearborn thus issued orders to the Army post at Kaskaskia, in Illinois, to pick out “one Sergeant & Eight good Men who understand rowing a boat.” The men were to accompany Lewis with “the best boat at the Post,” and plan on returning to Kaskaskia before winter ice locked up the Missouri.[4]Jackson, 1:103.

The Expedition’s planners in Washington possibly had in mind the powerful Sioux bands known to live high up the Missouri. Besides carrying expedition baggage, the boatload of Kaskaskia soldiers could act as an escort for the barge until an intimidating military force was no longer needed, and then come home. That idea kept changing, but Dearborn’s order helped shape Lewis’s eventual strategy for getting his expedition launched. Abandoned was the old notion of crossing the continent with a single contingent. Instead, the expedition would function in modern terms like a two stage rocket, with an initial booster that falls away when spent while the payload goes on alone.

Notes

| ↑1 | Arlen J. Large, “‘Additions to the Party’: How an Expedition Grew and Grew,” We Proceeded On, February 1990, Volume 16, No. 1, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original full-length is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol16no1.pdf#page=4. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Jackson, Donald, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. (University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 1978), 2:656. |

| ↑3 | Hawke, David Freeman, Those Tremendous Mountains. (W.W. Norton, N.Y., 1985 paperback ed.), 11. |

| ↑4 | Jackson, 1:103. |