Drifting at River Dubois

Clark took the barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) to the Mississippi-Missouri junction to set up a winter camp, while Lewis went to see the local authorities in St. Louis. Carlos Dehault Delassus, the Spanish commandant there, reported to his superiors that Lewis was accompanied by a “committee” of 25 men.[2]Jackson, 1:143. Delassus said he got this number from Lewis himself, but he didn’t explain how Lewis was counting. In fact, from this point until the following April it’s impossible to keep precise track of the expedition’s roster.

People kept drifting in. On 22 December 1803, George Drouillard arrived at Clark’s Camp Dubois with the eight lost soldiers from Southwest Point. They were a disappointing lot, except for Corporal Richard Warfington. At some point two local experts on Missouri River travel, Pierre Cruzatte and François Labiche, agreed to help manage the barge.

People kept drifting out. Four of the sadsacks from Southwest Point proved too sorry to keep. An individual name Leakens, recruited from somewhere, was discharged for theft. A local legend even had it that two men died and were buried in a nearby cemetery, but that tale is confirmed nowhere else.[3]Chuinard, Eldon G., Only One Man Died. (Arthur Clark Co., Glendale, 1979), 184–185.

Preparing for the Sioux

In the winter of 1803–1804, the officers began serious evaluation of the manpower that would be needed. As a freezing January wind blew outside his hut, Clark juggled options for an initial party of 25 men, or 30, or 37, or 50. “Those Numbers,” Clark noted in his journal, “will Depend on the probability of an opposition from roving Parties of Bad Indians which it is probable may be on the [river].”[4]Osgood, Ernest Staples, ed., The Field notes of Captain William Clark. (Yale University Press, New Haven, 1964), 21, 203. For some reason he later crossed that remark out, but the captains were indeed getting some alarming intelligence about the power of the upriver Sioux. One Missouri trader reported they had between 30,000 and 60,000 men, “and abound in fire-arms.”

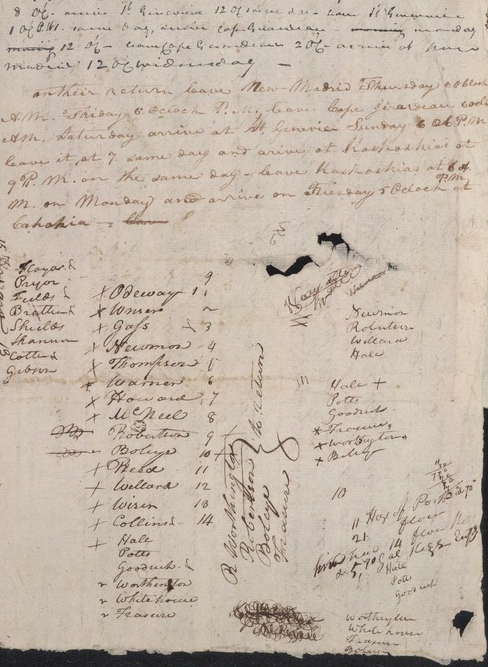

Not surprisingly, the captains opted for a big group. On 1 April 1804 they posted a list of 25 soldiers who would make up the “perminent Detachment.”[5]Moulton, Gary E., ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. (University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 1986), 2:187–189. (Cruzatte and Labiche would be formally added as permanent party soldiers later, at St. Charles.) Also, four soldiers (plus two later) were assigned to the escort boat, to return before winter. In St. Louis, Lewis hired eight civilian boatmen who consented to go only as far as the Knife River Villages (another may have joined later). The two officers, Drouillard and York would bring the total departing force to 45 men. “Those additions to the party,” Clark told interviewer Biddle in 1810, “were for carrying the stores as well as for protection in case of hostilities from the Indians who were most to be dreaded from Wood river to the Mandans.”[6]Jackson, 2:534.

To Lewis it must have seemed ages since he acquired enough equipment for just 15 people. After arriving in St. Louis, he started buying new supplies. When the barge and two open boats called pirogues left Camp Dubois on 14 May 1804, they carried 30 blankets instead of the original 15, and 63 pairs of socks instead of 36. More mouths to feed would require more hunting, so there was an augmented stock of flints and gunpowder. Added to the original 15 Harpers Ferry rifles were the regulation issue weapons that each of the transferred soldiers probably brought from their previous units.

Was Jefferson in the Dark?

Captain Stoddard, the new American military commander in St. Louis, gave Dearborn a report on the departure of the expedition’s three “well manned” vessels, but he didn’t say how well. it’s an open question whether anyone in Washington at that point knew that the exploring party had more than doubled in size. Surviving War Department records leave a clear paper trail governing the expedition’s strength until Lewis’s departure from Washington, but then the trail vanishes. There’s no evidence that Dearborn ever rescinded the order limiting the number of soldiers to 12, or that Lewis ever asked him to.

It’s certainly possible that Lewis cleared the expedition’s expansion directly with Jefferson in communications that have not survived. From Louisville, say, Lewis could have sent word that he needed a stronger force, conceivably in the “artichokes” cipher that the two had reserved for sensitive messages. Jefferson could have passed along a verbal okay to Dearborn, and then burned Lewis’s message.

Yet there’s a strong clue that all during the expedition’s big manpower buildup that fall and winter, Jefferson remained in the dark about any departure from the original plan. On 13 March 1804, the President wrote a long letter to William Dunbar in Natchez, saying in part:

I formerly acquainted you with the mission of Capt. Lewis up the Missouri and across from its head to the Pacific. he takes about a dozen men with him, is well provided with instruments, and qualified to give us the geography of the line he passes along with astronomical accuracy. he is now hutted opposite the mouth of the Missouri ready to enter it on the opening of the season. he will be at least two years on the expedition.[7]Jefferson to Dunbar, 13 March 1804. Jefferson Papers. Library of Congress.

There was no reason for Jefferson to mislead Dunbar, one of his closest scientific pen pals. Elsewhere in that letter, the President asked the Natchez surveyor and astronomer to draw up plans for a new U.S. expedition up the Arkansas River by—what else?—an officer and “10 or 12 picked soldiers.” (See Hunter and Dunbar Expedition) If Jefferson knew Lewis had already broken the old Alexander Mackenzie mold, he might have given Dunbar more flexibility.

Notes

| ↑1 | Arlen J. Large, “‘Additions to the Party’: How an Expedition Grew and Grew,” We Proceeded On, February 1990, Volume 16, No. 1, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. Editorial additions include page titles, side headings, and graphics to assist the web-based reader. The original full-length is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol16no1.pdf#page=4. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Jackson, 1:143. |

| ↑3 | Chuinard, Eldon G., Only One Man Died. (Arthur Clark Co., Glendale, 1979), 184–185. |

| ↑4 | Osgood, Ernest Staples, ed., The Field notes of Captain William Clark. (Yale University Press, New Haven, 1964), 21, 203. |

| ↑5 | Moulton, Gary E., ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. (University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 1986), 2:187–189. |

| ↑6 | Jackson, 2:534. |

| ↑7 | Jefferson to Dunbar, 13 March 1804. Jefferson Papers. Library of Congress. |