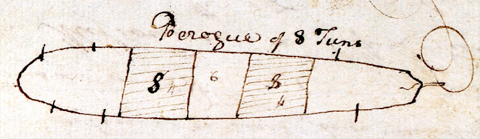

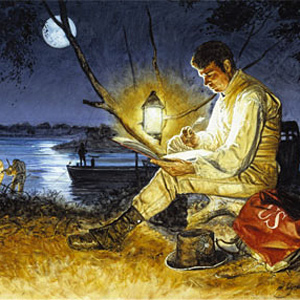

Clark’s Sketch of the White Pirogue

To see labels, point to the image.

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

The white pirogue was manned by a detachment of soldiers who were to haul provisions and escort the Expedition for 40 days. As it turned out, it went all the way to the Great Falls of the Missouri and back.

Under way on the Missouri, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark divided the crews of their three boats according to job status. The permanent party was segregated on the military barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’), probably to build its team spirit for the perilous future. Corporal Richard Warfington commanded the white pirogue‘s escort party of five other soldiers, while the eight (or nine) French watermen paddled the red pirogue. Here was the Expedition’s first stage booster at full thrust; both pirogues, then, were essentially cargo vessels, helping carry the initial burden of such store bought consumables as pork and flour until the party reached big game country on the plains.

Early Changes

The Expedition lost its first man within a month. On 12 June 1804, the party encountered some fur laden canoes headed for St. Louis. “Sent One of Our Men Belonging to the white pierouge back,” reported Joseph Whitehouse, a private on the barge, who gave neither the escort soldier’s name nor the reason for his departure.[2]Thwaites, 7:35. Whitehouse said only that the man dumped into a downriver fur canoe had belonged to Stoddard’s artillery company, so it might have been either Ebenezer Tuttle or Isaac White.[3]Another probable transfer from Capt. Stoddard’s company, Corporal John Robinson, was assigned to the escort squad in the 1 April 1804 roster posted at Camp Dubois. Thereafter his name vanishes … Continue reading The explorers actually made a swap with the canoeists, picking up Pierre Dorion, Sr., the first of a series of Indian trading oldtimers who acted as temporary interpreters.

By August the expedition had passed the mouth of the Platte River, and more men were lost. Moses Reed deserted his permanent party comrades on the barge, and a hired boatman named La Liberté left the red pirogue. La Liberté got away, but deserter Reed was punished by the gauntlet and fired from the permanent party. The captains later promoted Robert Frazer, one of the escort soldiers, to fill Reed’s vacancy on the barge. On 20 August 1804, the Expedition was saddened by the death of Sergeant Charles Floyd at present-day Council Bluffs, Iowa, probably of a burst appendix.

Jefferson’s Enlightenment

By now Jefferson probably had an inkling of how big the operation had become, if he didn’t before. In mid-July a delegation of Osage Indians arrived in Washington to see him, having left St. Louis just as Lewis and Clark started up the Missouri. The chiefs were escorted by Pierre Chouteau, a St. Louis merchant who knew the Expedition’s departing strength. Jefferson surely would have asked Chouteau for particulars. Also that summer somebody—perhaps a trader named Fairfong—went downriver to St. Louis to give an account of the Expedition’s progress. His much garbled report eventually reached Jefferson. here’s how the President relayed the information in a 6 November 1804 letter to Lewis’s younger brother, Reuben:

“Two of his men had deserted from him. he had with him 2. boats and about 48 men. He was then setting out up the river. One of his boats & half the men would return from his winter quarters. In the Spring he would leave about a fourth where he wintered to make corn for his return, & would proceed with the other fourth.”[4]Jackson, 1:216.

Dealing with Cargo

Wherever the old notion of a squad of Army corn planters originated, it allowed Jefferson to use some creative accounting to shrink the reported 48-man mob to a final party of just 12—the familiar number planned.

It’s unlikely that Lewis and Clark were trying to deceive Washington by floating such an untrue story. All along, they had planned to make a firsthand official accounting of this leg of the trip, by means of a pirogue sent back with the escort soldiers from Kaskaskia. After passing the Platte the captains started preparing a map and “despatches” about the journey thus far, work that continued until the boats reached modern South Dakota. But there, the plan changed again. The heavily loaded barge kept bumping its bottom on sandbars, slowing the whole fleet. On 16 September 1806, the captains decided both pirogues were needed to carry cargo transferred from the laboring barge, meaning that the escort soldiers would have to stay with the Expedition all winter. Curiously, Clark’s journal justified this switch solely in boat-handling terms, with no hint the captains anticipated the following week’s dangerous encounter with the Teton Sioux [Lakota Sioux Difficulties]—supposedly a major reason for taking the escort’s extra guns in the first place.

Fort Mandan Adjustments

It was beyond the Tetons that another permanent party explorer was lost. John Newman, a barge man, was “discarded” to the red pirogue for talking mutiny. When the Expedition stopped at the Knife River Villages for five months of North Dakota winter, the captains enrolled in the Army a resident Canadian, Jean-Baptiste Lepage, to fill Newman’s slot. Because Floyd hadn’t been replaced, the permanent party’s roster of enlisted men was still one shy of the 27 that had begun the trip. A replacement in fact was at hand. Hanging around Fort Mandan was François-Antoine Larocque, a clerk for Britain’s North West Company, who asked to join the Expedition. One big purpose of the trip was to lure Western Indians away from their trade connections with Larocque’s company, so the captains not surprisingly turned him down.[5]See also Larocque at Fort Mandan.

And yet the Expedition kept growing. Montreal-born Toussaint Charbonneau, hired as a temporary Hidatsa interpreter at Fort Mandan, agreed to go the whole way to the Pacific. With Drouillard, that gave the party two civilian interpreters. The captains also thought Charbonneau’s Lemhi Shoshone wife, Sacagawea, could do some useful interpreting once the explorers reached her tribe’s country in the Rockies. And if you took Sacagawea, you also had to take her newborn son Jean Baptiste Charbonneau.

Parting Ways

In April 1805, the Expedition’s two stage rocket separated. The Pacific bound payload party, numbering 33 souls, continued up the Missouri in the two pirogues and six newly hewn dugout canoes. The barge fell away to St. Louis with Corporal Warfington’s escort soldiers (now including deserter Reed and mutineer Newman) and the French watermen. The trustworthy Warfington carried a Lewis letter to Jefferson that, perhaps at long last, gave the government an official count of the party’s final size.[6]Jackson., 1:232. In numbering his total party at 33 for Jefferson, Lewis included a Mandan Indian who soon dropped off, but omitted Sacagawea’s infant, leaving no net change for the Pacific … Continue reading Lewis also sent Dearborn a now missing muster roll of his 26 soldiers. Jefferson received Lewis’s letter on 13 July 1805, but waited until the following February to include it in a report to Congress, three years after it had authorized a tour by one officer and 10 or 12 men.

In his letter Lewis also promised to send back three or four men in a canoe, with updated journals, once the party reached the Missouri’s head of navigation. But by early July, having completed the tough portage around the river’s falls in Montana, the officers once again decided not to risk a reduction in strength. Lewis believed the worst part of the trip was now beginning, with nobody knowing whether the Indians ahead would be friends or enemies. “We have conceived our party sufficiently small and therefore have concluded not to dispatch a canoe with a part of our men to St. Louis as we had intended early in the spring,” Lewis wrote on 4 July 1806.

Pacific Leavings

A conviction that every man was needed again kept the captains from reducing the group as it prepared to head home from the mouth of the Columbia in March 1806. Finding no ships there, the captains might have left two men behind anyway to wait for a vessel to take them and a copy of the records home by sea, as Jefferson contemplated. “Our party are too small to think of leaveing any of them,” said Clark on 18 March 1806. Less than a month later, with the explorers menaced by crowds of insolent Columbia River Indians, Clark thanked his stars for keeping a force big enough to deter real trouble: “Nothing but the strength of our party has prevented our being robed before this time.”

| *Meriwether Lewis *William Clark *York | ||

| Clarksville | Fort Massac | Kaskaskia |

|---|---|---|

|

*William Bratton *John Colter *Joseph Field *Reubin Field Charles Floyd *George Gibson *Nathaniel Pryor *George Shannon *John Shields |

*George Drouillard† John Newman *Joseph Whitehouse |

John Boley *John Collins John Dame *Patrick Gass *John Ordway *Ebenezer Tuttle *Peter Weiser Isaac White *Alexander Willard *Richard Windsor |

| Fort Southwest Point | St. Charles | Fort Mandan |

|

*Hugh Hall *Thomas Howard *John Potts Richard Warfington |

*Pierre Cruzatte *François Labiche |

*Toussaint Charbonneau† *Sacagawea† *Jean Baptiste Charbonneau† *Jean-Baptiste Lepage |

Previous Army units, if any, are unknown for *Robert Frazer, *Silas Goodrich, *Hugh McNeal, Moses Reed, *John Thompson, and *William Werner. Also, the departing group included eight or nine French boatmen who went as far as Fort Mandan.

*Permanent party who journeyed from Fort Mandan to the Pacific and back.

Conclusion

The documentary gaps in the story of the Expedition’s expansion may never be filled. Even if no messages were deliberately destroyed, some Army records were lost forever when British troops set fire to the War Department in 1814. The available evidence points to a mixture of reasons for abandoning the Alexander Mackenzie precedent. Lewis first underestimated the number of men needed to manage his barge; whether from Nashville or Pittsburgh. Everyone eventually realized it would be too risky for a small group to brazen its way past the Sioux.

Once the permanent party was fairly on the road from Fort Mandan, the leaders felt they had struck an equilibrium level of ideal strength for their mission, and resisted any idea of cutting it back. And it finally made little difference whether headquarters authorized a bigger party or merely acquiesced later; in the end the government honored its payroll obligations to all the men, and the officers apparently got into no trouble. What counted was the determination of the field commanders to take control of the Expedition’s size, showing at the very outset the kind of bold leadership that arched a continent.

Related Pages

William Clark (1784–1838)

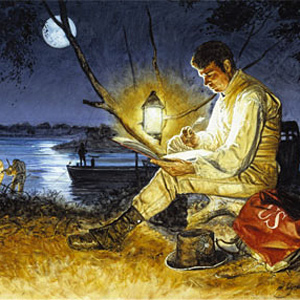

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Clark was a highly intelligent man, and in terms of the practical knowledge required to make his way in the wilderness, to lead men, and to succeed in the world of frontier politics, he was highly educated and consummately effective.

Meriwether Lewis

Explore the complex character and history of Meriwether Lewis before, during, and after the expedition.

Sacagawea

Articles and journal entries

Speaking Hidatsa and Shoshone, she was an interpreter beyond value yet never on the payroll. Still, Sacagawea remains the third most famous member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

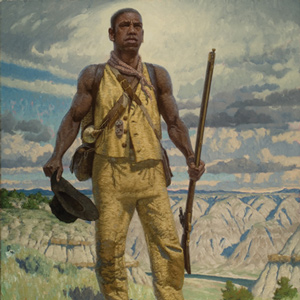

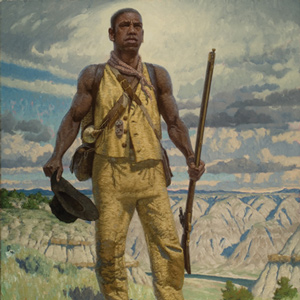

Two years after the conclusion of the historic Lewis and Clark expedition, York and his enslaver, the Virginia-born patrician William Clark, were at odds.

Seaman

Whether he was Lewis’s pet or the expedition’s working dog—or both—he was likely smaller than today’s Newfoundland dog. Did he get lost on the way home or was he present at Lewis’s death?

On 11 May 1805, Bratton appeared, running toward the river and yelling to be taken aboard quickly. He had shot a grizzly through the lungs, and the wounded bear had chased him for half a mile. The bear had lived at least two hours after first being shot.

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau

by Kristopher K. Townsend

This 9-page series examines the life of Jean Baptiste Charbonneau—the infant son of Sacagawea who traveled across the continent with the Lewis and Clark Expedition. He was educated in St. Louis and Europe, a mountain man, military guide, and California miner.

Toussaint Charbonneau

by Barbara Fifer

The fur trade had put Charbonneau in place to meet the captains and join their expedition. He was the oldest expedition member would outlive most of his fellows as he followed the rigorous life of a fur trader, guide, and interpreter.

He had gotten off to a bad start, but apparently, the captains, or at least Clark, saw something in him that was worth saving. They would name Idaho’s Lolo Creek, Collins Creek.

Colter left a legacy of western lore, not the least of which was his famous run from the Blackfeet Indians and his exploration of “Colter’s Hell.” Yet his contributions to the expedition were also many.

Cruzatte’s skills in piloting boats were called on frequently during the expedition. As the main fiddle player, his music brought life to many a celebration. In addition, he could speak Omaha.

Drouillard was one of the captains’ three most valuable hands. He was also the highest paid member after the captains, he shared the Charbonneaus’ tent with the family and the captains, and he was the only man Clark seemed to call by first name in the journals.

Joseph Field

by Barbara Fifer

Joseph yelled to his brother Reubin, who was instantly awake, and the two sprinted for fifty to sixty paces after the natives who were clutching their guns.

Reubin and his brother Joseph (about a year older) were among the best hunters, but Reubin was possibly the better shot. He was, at least, at Camp Dubois on 16 January 1804, when Clark’s men set up a shooting match with some local residents.

Charles Floyd

(1783–1804), Sergeant

Floyd began his journal on 14 May, the day of the expedition’s departure from Camp Dubois. On August 18th Floyd wrote his last entry. Shortly after noon on the 20th, Charles Floyd died “with a great deal of composure.”

At a place where “one false Step of a horse would be certain destruction,” Frazer’s pack horse took that fateful step, lost its footing and rolled with its load “near a hundred yards into the Creek,” over “large irregular and broken rocks.”

Starting out as a private with a specialty of carpentry, Gass was soon elected a sergeant after the death of Sergeant Charles Floyd. His was the first expedition journal to be published. He was also the last surviving member.

The captains sent four men to retrieve Gibson, “who is so much reduced that he cannot stand alone and…they are obliged to carry him in a litter.” They arrived on February 15, and Lewis went to work sweating the “veery languid” Gibson with saltpeter and dosing him with laudanum for sleep.

Silas Goodrich

(possibly 1778–unknown), Private

Silas Goodrich was the expedition’s principal fisherman. He also did well when trading for food with Indians from time to time.

Hugh Hall

(b. 1772 and d. between 1820 and 1831), Private

As if to confirm the captains’ poor evaluation of the new arrivals from Fort Southwest Point, a scant nine days after his arrival, Hall was among a group of six or seven men who got drunk on New Year’s Eve.

On 23 January 1806, Lewis dispatched Howard and Werner to the Salt Camp on the ocean beach, to bring back a supply of salt. When they had not returned by the 26th, Lewis feared they had gotten lost.

Labiche performed all the regular duties of an army private, but also performed well as a French and English interpreter. He would continue serving as an escort with Lewis for Chief Sheheke’s delegation to Washington City.

At the age of 43, Lepage was the oldest member of the expedition. He was a French-Canadian trapper and had lived among the Mandan prior to the expedition. His most embarrassing moment may have been losing the pack horse with Lewis’s winter clothing.

Lewis wrote that “McNeal had exultingly stood with a foot on each side of this little rivulet and thanked his god that he had lived to bestride the mighty & heretofore deemed endless Missouri.”

Ordway’s journal is the only one carries an entry for every one of the trek’s 863 days. Just after the expedition ended, Ordway had purchased the land warrants issued to Jean-Baptiste Lepage and William Werner.

John Potts

(ca. 1776–1808), Private

At Long Camp, Potts nearly drowned when the dugout canoe he was in was swamped in the Clearwater River. But Potts’s worst accident happened when the Corps retraced the Northern Nez Perce Trail through the Bitterroots.

Pryor was assigned several special missions from exploring the Sandy River to escorting Mandan Chiefs to Washington City. He would barely survive his adventures on the Yellowstone River.

Shannon had found the horses, then “Shot away what fiew Bullets he had,” failing to get any meat. Eventually, he carved a bullet from a stick and got a rabbit–his only food other than wild grapes during more than two weeks.

John Shields

(1769–1809), Private

During the damp winter at Fort Clatsop and throughout 1806, the journals speak more and more often about Shields’ life-sustaining work as gunsmith. Certainly the guns had seen hard use.

On 8 October 1805, the canoe split open and took on water. The Corps encamped for two days to dry out the goods, allowing Thompson to heal a bit.

Weiser was a member of Sgt. John Ordway’s detachment that paddled the canoes back to the Great Falls. During the 1806 portage around the Falls of the Missouri, he suffered a disabling accident.

William Werner

(unknown–ca. 1839), Private

He went with Clark to Ecola Creek on the January 1806 blubber-trading expedition, afterwards being dropped off to take a turn at Salt Camp. He returned to his home state to become a well-established Virginian farmer.

His journal begins, “about 3 Oclock P.M. Capt. Clark and the party consisting of three Sergeants and 38 men who manned the Batteaux and perogues. we fired our Swivel on the bow hoisted Sail and Set out in high Spirits for the western Expedition.”

Including a court martial, charging grizzlies, and a mile-long swim down the Missouri River, Willard’s adventures are well-documented in the journals. He survived them all, crossing the Missouri a final time on his way to California, at age 74.

Windsor helped recover three orphaned grizzly bear cubs of a sow they killed on a hunt in early April of 1806. According to Lewis, they traded the cubs to some coastal Indians, who, “fancyed these petts and gave us wappetoe in exchange for them.”

Notes

| ↑1 | Arlen J. Large, “‘Additions to the Party’: How an Expedition Grew and Grew,” We Proceeded On, February 1990, Volume 16, No. 1, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original full-length article is provided at https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol16no1.pdf#page=4. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Thwaites, 7:35. |

| ↑3 | Another probable transfer from Capt. Stoddard’s company, Corporal John Robinson, was assigned to the escort squad in the 1 April 1804 roster posted at Camp Dubois. Thereafter his name vanishes from the Expedition’s records, including a list of boat crews posted just beyond St. Charles on 26 May 1804 (Moulton, 2:254–256). He may have washed out before departure. |

| ↑4 | Jackson, 1:216. |

| ↑5 | See also Larocque at Fort Mandan. |

| ↑6 | Jackson., 1:232. In numbering his total party at 33 for Jefferson, Lewis included a Mandan Indian who soon dropped off, but omitted Sacagawea’s infant, leaving no net change for the Pacific bound group. |