Meriwether Lewis was on horseback both at the beginning and end of his appearance in the pages of history. Each time he was haunted by horse mishaps.

In early March 1801 Lewis had set off from Pittsburgh, headed for Washington, traveling with three horses, to accept the appointment as President Jefferson’s private secretary, which ultimately led to the Lewis and Clark Expedition.[2]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), vol. l, 4n. One horse went lame on the rugged, muddy roads. Delayed by this disability, Lewis did not reach Washington until three weeks later, April 1st–an inordinate delay for accepting an important presidential assignment.

And in the final days of his life, eight years later, he again headed for Washington on horseback, this time from St. Louis to defend his expeditionary expense accounts. On the Natchez Trace en route two of his horses were lost in the Wilderness, forcing his companion, Major James Neelly, to remain behind to search for them.[3]Ibid, vol. 2, 467–68. Lewis rode ahead alone, apparently in a distracted state, to lonely Grinder’s Stand where his tragic death occurred by gunshot wounds 9 October 1809. It was a death which might have been averted had Neelly not been absent searching for lost horses.

Lewis’s horses thus furnished both a preface in 1801, and a somber epilogue in 1809, of the difficulties he had with his mounts on the Expedition of 1804–1806. For it was on horseback that Lewis, his co-leader William Clark, and their men faced their most dangerous trails. Yet despite the critical importance of these animals in the Lewis and Clark drama, there appear to be no paintings or images of any kind in the pictorial record depicting the two captains astride horses. Typically, they are shown standing on a promontory overlooking rivers and mountains, pointing forward, or poised in the prow of a canoe, or grouped with native chieftains parlaying in the wilderness. Rarely, if ever, do horses (other than native mounts) show up in the graphic literature of the expedition.

A Subservient Domination

But without their horse luck Lewis and Clark may have been just two other minor figures in the opening of the West. It was only through their fortuitous purchase of horses from the Shoshone Indians on the edge of the Rocky Mountains, August 1805, that their mission was saved from probable defeat. Those purchases enabled them to stumble with their baggage across “those turrible mountains.” Staving off starvation by eating “killed colts,” they managed to reach the Pacific watershed before winter could shut them down. Thanks to their horses they would proceed on to fulfill a mission critical to the new nation’s future. The Expedition thus became unique testimony to the precept that “man on a horse’s back is history’s dominant figure.”[4]Glenn R. Vernam, Man on Horseback (New York: Harper & Row, Inc., 1964), ix.

As horsemen however, Lewis and Clark were not very “dominant.” Instead, at times on horseback they seemed pathetic and bedraggled, more like Quixote than heroic cavaliers worthy of statues in the court house square. Their men also, when dependent on horses, were often a disheveled, disoriented bunch, especially on the Lolo trail, bungling along in front of, or behind, or astride their equally pitiful nags. Lewis himself called this stretch with the horses the most “wretched portion of our journy, the Rocky Mountain, where hungar and cold in their most rigorous forms assail the waried traveller; not any of us have yet forgotten our sufferings in those mountains . . . and I think it probable we never shall.”[5]Gary E. Moulton, ed. The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991), vol. 7, 325. All quotations or references to journal entries in the ensuing text … Continue reading

The Horse Trail

What was the actual geographic extent of the Lewis and Clark horse trail? Captain Clark measured it out in his “Postexpeditionary Miscellany.”[6]Ibid, vol. 8, 388 et seq. After river mileage of 3096 miles westward up the Missouri, the party went by land, i.e. by horse, from the Shoshone encampments (near the present day southwestern Montana-Idaho border) “over to Clark’s river and down that to the enterance of travellers rest Creek . . . thence across the ruged part of the Rocky Mountains to the navagable branches of the Columbia 398 Miles.” Eastbound on the return trip, the party had the help of horses from present-day Dalles on the Columbia, overland at least 360 miles to the Nez Perces, thence back to Travelers’ Rest. From there, directly across the mountains to the plains and the Great Falls of the Missouri was a distance of 340 miles. Though the party was divided into different groups, all with horses, at Travelers’ Rest each of these groups on their different routes would have traversed at least a minimum of the 340 miles cited by Clark as the distance between Travelers’ Rest and the Great Falls. There were, of course, additional daily sorties of hunters and special rides (such as Lewis’s all night gallop of 120 miles from the fight with the Blackfeet at the Two Medicine River site).

In short, the Expedition left horse tracks of at least four to five hundred miles on a westward lineal course, plus at least a thousand miles easterly, widely scattered over strikingly varied terrain—with horses ranging in number from two or three at a time up to 65. The Corps of Discovery had become, in effect, a kind of cavalry unit for a cumulative period of six months during its approximate 28 months of absence from St. Louis. These men had then to manage a large squadron of unruly animals on which they were absolutely dependent for surmounting the most dangerous fifth of the total round trip.

One-side of a horse pack

Display at Fort Walla Walla Museum. Photo © 2015 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Small Pack Saddle

© 2017 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The Expedition did not bring saddles and pack saddles. Nor is it likely they had enough buckles and rope to make the well-rigged saddles and packs shown in these two figures. They would need to make, or purchase from the Indians, their own rigging. For examples of Indian rigging, see Horse Trading: The Prices Paid.

—Kristopher Townsend, ed.

A Lack of Preparedness?

How did the corps measure up in horsemanship? Tracking their hoofprints reveals a curious mixture of ingenuity and instinctive skill adapted to the circumstances—but also ineptitude, incompetence, and at times inexplicable negligence. It was not until the winter at Fort Mandan (1804–5) that the need for horses began to dawn on them. Previously, the two captains could hardly have realized the extent to which they would become horse traders, horse managers, horse doctors, horse breakers, horse trainers—horse factotums!

Once in possession of these animals, from the Shoshones onward, the men were constantly frustrated in managing them. Rarely did a day pass while moving on the trail when one or more of the horses had not been lost, strayed, stolen or injured. Untold hours were wasted searching for missing animals, or recovering from accidents. Could these troubles have been avoided? Did the horse problems result simply from the circumstances of the voyage, the weather, the geography? Was the corps properly prepared with the needed skills, know how, plans for dealing with the circumstances?

The Unforeseen Need

Consider first the pre-expeditionary planning for the journey: neither Lewis nor Jefferson appear to have foreseen any compelling need for horses or for training their men in horse management. Remember, however, that the Rocky Mountains weren’t there yet! The “height of land” notion still prevailed among geographers who looked to the unknown West. Conventional wisdom presumed a continental divide, comparable to the Alleghenies in the East, offering only a relatively narrow rise, not too formidable, separating the watersheds of the Missouri and the Columbia. Jefferson’s message to Congress of 18 January 1803 proposing the expedition contemplated continuing navigation on the Missouri River “possibly with a single portage from the western ocean . . .”[7]Jackson, vol. 1, p. 12. By implication, any need for horses would be merely incidental and transitory.

Jefferson’s Opinion of Horses

Besides, Jefferson seemingly had little use for horses. As early as 1785 he had expressed his disdain:

The Europeans value themselves on having subdued the horse to the uses of man; but I doubt whether we have not lost more than we have gained by the use of this animal. No one has occasioned so much the degeneracy of the human body. An Indian goes on foot nearly as far in a day, for a long journey as an enfeebled white does on his horse; and he will tire the best horses.[8]John P. Foley, ed., “Horses, Effect on Men” in The Jefferson Cyclopedia, A Comprehensive Collection of the Views of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1900), 398.

One wonders if Jefferson would want to eat those words 25 years later on reading the Lewis and Clark journals, learning how horses had saved the expedition from disaster, or imagining Lewis’s all night ride after the Thro Medicine fight.

As for Lewis, he most likely felt no need for horse competence beyond what he already possessed. He had lived and traveled as an army officer, a paymaster serving units in the Ohio Valley for years on horseback—a fitting career for a young man born and reared in Virginia, the land of renowned horseflesh. The same would have been true of his co-leader. Clark had had military experience with horses under General Anthony Wayne’s command in Ohio in the 1790s, leading pack trains of several hundred animals through the wilderness, and he certainly must have been at ease on horseback in his Kentucky environs. But could either captain have foreseen the unique problems for coping en masse with the restless, semi-wild animals of the natives on the prairies and in the mountains, so unamenable to the disciplined pack train requirement for expedition purposes?

Lewis’s brand on a keg of hulled corn

Taken in cooperation with the Fort Mandan Visitors Center. Photo © 2013 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Horses en Route

It comes then as no surprise that there is but one mention of horse-related items in the record of Lewis’s preparation before his embarkation from Pittsburgh on 31 August 1803: listed for shipment from the “U.States Military Dept.” 12 March–30 June 1803:

1 Packg Boxes for Horsemans Cloths-$1.[9]Jackson, vol. l, 92.

It is not clear from the journals how or when these “cloths” were used en route . . . Lewis had also arranged for shipment of a saddle from Monticello on leaving there for Pittsburgh. Jefferson wrote to him 11 July 1803: “your bridle left by the inattention of Joseph in packing your saddle is too bulky” to go by post.9 Did the bridle ever catch up with him, and did the saddle and bridle accompany him to Mandan and beyond? There seems to be no record to this effect. In any case, these minimal references in the otherwise voluminous documentation of items taken on the Expedition show scant attention to thoughts of horse travel in the Great West. Nor is there any mention in the cargo shipment references of Lewis’s branding iron, often assumed as intended for branding horses such as those left in the custody of the Nez Perces in the fall of 1805. It can be doubted, however, that Lewis’s iron, found in 1892 and now in possession of the Oregon Historical Society, was actually used to brand horses. [See especially, Note 14 at end of this article.] Lewis did use it at the Marias on 10 June 1805 “to put my brand on several trees” near the stashed red pirogue.

Pittsburgh to Fort Mandan

A few domestic horses did play a part in the voyage down the Ohio from Pittsburgh, thence to St. Louis, and later from St. Louis to Fort Mandan, most notably as follows:

- Lewis hired local farm horses on several occasions to pull the keel boat over sand bars in the Ohio River, then at record lows.

- At Camp Dubois near St. Louis in the winter of 1803–04, local animals were used for courier rides between the city and the camp.

- Two horses were acquired to accompany the party up the Missouri. These steeds helped tow the keel boat over difficult places and were occasionally used by the hunters roving on shore; one such episode figured in the near tragedy of 18-year-old George Shannon getting lost on the trail—”missing in action” for 12 days and having to abandon one of the two horses. The remaining horse was shortly after stolen by the Teton Sioux.

- While with the Mandan in winter’s grip the captains borrowed or hired local horses several times to pack buffalo meat in sleighs across snow fields; in another encounter with the Sioux two of these horses were stolen.

The Fort Mandan Plan

During the stay with the Mandan, numerous reports of Indian war parties stealing horses from each other dramatized to the captains how crucial horse trafficking had become amongst the natives. But as far as the corps itself was concerned, during these winter months the actual use of horses was occasional and incidental—not absolutely essential for the needs of the expedition.[10]See also on this site: Winter at Fort Mandan.

It was at Mandan that the captains first seriously faced up to their ultimate travel needs. Almost immediately on arrival there, they began to hear about the mountains to the west and the need for guides and land transportation beyond the river route. On 29 October 1804, before they had even located winter quarters, they learned that a chief of the Minnetaree (the Hidatsas) was then on a war party (to steal horses) “against the Snake Indian who inhabit the Rocky Mountains . . .” Just a few days later, 4 November 1804, Clark recorded that:

a french man by Name Chabonah who Speaks the Big Belly language visit us, he wishes to hire & informed us his 2 squars were Snake Indians, we engau him to go on with us and take one of his wives to interpret the Snake language.

During the long winter nights and days, as Lewis and Clark gained further information from their hosts about the westward route, those Snake Indians (i.e. the Shoshones) and their horses loomed ever larger in their plans. Lewis wrote to President Jefferson from Ft. Mandan, 7 April 1805, just as the Corps was to resume the journey upstream toward the mountains:

The circumstances of the Snake Indians possessing large quantities of horses, is much in our favour, as by means of horses, the transportation of our baggage will be rendered easy and expeditious overland, from the Missouri to the Columbia river.

Sacagawea = Horses

The horses would be not only “much in their favour,” they would be absolutely essential-explaining why the captains would dare to include Toussaint Charbonneau‘s wife, Sacagawea, a teenage girl with a new born babe, in a party entering upon such a hazardous journey. The theorem was self-evident:

- To reach the Pacific over the mountains requires horses

- The Snake Indians (the Shoshones) have horses

- We must talk their language to acquire their horses

- Sacagawea is a Shoshone and speaks the language

- Sacagawea is our key to horses, and THEREFORE our key to success

But the captains almost lost the key. On 6 June 1805, while Lewis was absent reconnoitering for the Great Falls, Clark recorded “our Indian woman verry sick I bleed her.” She became progressively worse over the next several days. By 16 June 1805, Clark thought she might die. The urgency of the situation struck Lewis forcefully as he rejoined the party after locating the Great Falls:

about 2 P.M. I reached the camp found the Indian woman extreemly ill and much reduced by her indisposition. This gave me some concern as well for this poor object herself, then with a young child in her arms, as from the consideration of her being our only dependence for a friendly negotiation with the Snake Indians on whom we depend for horses to assist us in our portage from the Missouri to the Columbia River.

Fortunately Lewis had also discovered Sulphur Springs nearby, “the virtues of which . . . [he] now resolved to try on the Indian woman.” His prescriptions were effective, and within a few days she had sufficiently recovered, able to proceed on—and later, to help in the horse talks with the Shoshones.

Appaloosa Horse

© 2010 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Mule

© 2011 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Where Are the Horses?

Once beyond the Great Falls of the Missouri, Lewis became increasingly aware that horses would be the only means of fighting against time and geography which were racing against him toward another winter. He voiced his worries on 27 July 1805:

we begin to feel considerable anxiety with rispect to the Snake Indians. if we do not find them or some other nation who have horses I fear the successful issue of our voyage will be very doubtful . . . now several hundred miles within the bosom of this wild and mountainous country . . .

Still no Indians in sight by 8 August 1805 as Lewis scouted ahead of the party with three of his men. His record of the day had a desperate note:

without horses we shall be obliged to leave a great part of our stores, of which it appears to me that we have a stock already sufficiently small for the length of the voyage before us.

Meeting the Shoshone

Finally, by 11 August 1805 near the Continental Divide, he made contact with the Shoshones. (For more on that, see Meeting the Shoshones.)

But Lewis was afraid the Shoshones could not be relied upon to make their animals available; many of the Indians were nervous, not yet ready to trust the strangers, suspecting a trap. Lewis feared they might bolt and disappear with their horses, which:

would vastly retard and increase the labour of our voyage and I feared might so discourage the men as to defeat the expedition altogether . . . I slept but little, my mind dwelling on the state of the expedition which I have ever held in equal estimation with my own existence . . .

There would indeed be further nightmares before the captains could determine “whether to prosecute . . . [the] journey from thence by land or water.” On 17 August 1805, Clark and the main party were reunited with Lewis, and the Shoshones became more trusting—”the sperits of the men were now much elated at the prospect of getting horses.” Still, the Captains remained uncertain whether to continue by horseback or canoe.

Horse Trading Begins

Clark set off with eleven men armed with axes for canoe building, to reconnoiter the Salmon River. Several days of stumbling over dangerous terrain and viewing impossible canyons convinced him that the Indians had been right all along in ruling out such a route. He sent a letter by messenger to Lewis, who remained with the Shoshones, advising that land travel by horse appeared the only feasible course.

In the interim, Toussaint Charbonneau had learned that the Shoshones were about to leave surreptitiously with their horses for the buffalo country; he had neglected to tell Lewis until almost too late. “I could not forbear speaking to him with som degree of asperity,” Lewis noted. He knew that his chance of obtaining additional horses could suddenly disappear, and he lost no time in cajoling the Shoshone chiefs to countermand their movement orders. After this new nightmare of vanishing horses, on receipt of Clark’s letter, Lewis promptly determined to commence the purchase of at least 20 additional animals, still fearful that “the caprice of the indians might suddenly induce them to withhold their horses . . .”

It was here that the horse trading careers of the two captains began in earnest. They offered uniform coats, shirts, leggings, knives, handkerchiefs, axes, and trinkets (in one case even Clark’s pistol with powder and balls) for animals which they considered generally in excellent condition, though later they would complain about sore backs and previous overuse of these animals. By 30 August 1805, they had purchased 29 or 30 (the number varies in their records) to begin their journey into the Bitterroot Mountains. Ten more were acquired further along the route when they encountered a band of Flathead Indians who had abundant herds. By 16 September 1805, 40 horses plus three colts were on hand; some of the men thus had to manage two horses each during this most difficult segment of the journey.

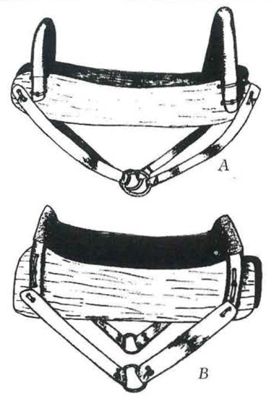

Rawhide Stirrup

Mandan Saddle (bottom)

Photo © 2013 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

When making their purchases, the captains generally recorded the prices paid for their animals. These prices varied considerably at different stages of the journey.

Prices Paid

From the Shoshones, the captains had acquired animals of varying quality for merchandise valued at around $6.00 per head on average. This was a remarkably good price when compared with what Lewis had earlier observed on the lower Missouri domestic frontier. Recall that on his way to St. Louis from the East Lewis had visited Louis Lorimier, the well-known horseman at Cape Girardeau. There, he wrote on 23 November 1803, that among the “uncivilized backwoodsmen” in that area “the circulating medium is principally Horses . . . for 50 to $200.” This contrast between the wilderness prices and the frontier prices was blithely exaggerated when Lewis wrote up his commentary on the horse market while at Fort Clatsop on the Pacific. On 15 February 1806, deflating the $6.00 prices paid to the Shoshones, he stated that “an eligant horse may be purchased of the natives for a few beads and other paltry trinkets which in the U.States would not cost more than two dollars.”

On the return journey, however, when the captains desperately needed horses to maneuver back up to Nez Perce country, they had to bargain with the unfriendly Eneshers and Skillutes. These groups either refused to sell or charged “extravagant prices”—double the prices paid to the Shoshones and the Flatheads; and this at a time when the corps ultimately needed twice the number of horses used while westbound, and was also nearly impoverished in the number of trade goods with which to bargain. “Two handkerchiefs would now contain all the articles of merchandize which we possess,” Lewis recorded 16 March 1806 at [Fort] Clatsop.

A Capital Investment

Thus practically destitute, the captains then seem pitiful in their bargaining—reduced to offering their personal, “last resort” property: Clark ponied up his own blanket, coat, sword, and plume; Lewis, his dirk. They were literally trading the shirts off their own backs, but to no avail. “I used every artifice decent & even false Statements to enduce those pore devils to sell me horses,” Clark said. “I could not precure a Single horse of those people . . . at any price.” The captains then had no more to deal with than their bare hands for trade purposes.

But their manual skills finally did prove more effective than merchandise. Clark had achieved a reputation as a physician among the natives as he dressed sores, relieved back pains, and gave small things to a chief’s children. In due course the medical practice produced horses when other stock in trade had been spurned or bargained away.

By May 1806 when the corps reunited with the Nez Perces, practically the entire capital of the expedition had been invested in horses, a seemingly risky commitment when the party was still thousands of miles from home and not yet over the mountains. Moreover, this investment would erode. Horses had become the “life blood” of the Expedition, and were subject to debilitating losses.

| Date | Seller | Price Paid |

|---|---|---|

| 18 August 1805 | Shoshone | 3 “very good horses . . . uniform coat, pair ofleggings, a few handkerchiefs, three knives, and some other small articles . . . about 20 $ in the U. States.” |

| 19 August 1805 | Shoshones | “A good mule cannot be obtained for less than three and sometimes four horses and the most indifferent are rated at two horses. their mules generally are the finest I ever saw without any comparison.” |

| 22 August 1805 | Shoshones | 5 “good horses” @ “six dollars a peice in merchandize” |

| 24 August 1805 | Shoshones | 3 horses; for each: “an ax, a knife, handkerchief and a little paint;” 1 mule; same as above plus “another knife, shirt, handkerchief & pair of legings” (price was double that for a horse) |

| 23 October 1805 | Chinooks | for “this butiful one” Lewis gave “our smallest canoe” plus “a Hatchet & few trinkets” |

| 18 April 1806 | Skillutes Eneshers |

4 horses @ double price paid to Shoshones and Flatheads. 2 horses, as payment for medical treatment (and massage) of Chief’s wife, trinkets to children; 1 horse for “a large kittle.” 4 horses for “two of our kettles.” |

| 20 April 1806 | Eneshers | Clark offered “a blue robe, callico shirt, a handkerchief, 5 parcels of paint, a Knife, a wampom moon, 4 braces of ribin, a piece of Brass and about 6 braces of yellow beeds, also my large blue blanket for one, my Coat Sword & Plume none of which seem to entice these people.” |

| 23 April 1806 | ? | Charbonneau bought one horse for a “Shirt & 2 lether Sutes of his wife.” |

| 28 April 1806 | Wahhowpuns | 1 white horse “very elegant” Chief Yellepit wanted a kettle. Instead Clark gave his “Swoard, & 100 balls & powder & Some Small articles.” |

| 29 April 1806 | Wahhowpuns | 2 horses, Lewis gave medals, sundry articles & “one of my case pistols and several hundred rounds of ammunition.” |

| 5 May 1806 | ? | 1 “eligant grey mare” for a phial of eye water and opening an abscess. |

A few of the many misfortunes, both westward and eastward, which drained the reserve of horses are recapped here below:

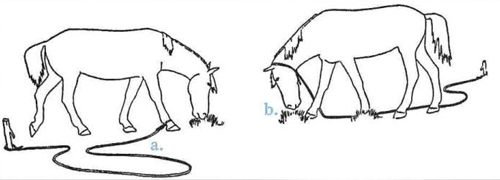

Picketed Horses

John C Ewers, “The Horse in Blackfoot Indian Culture,” Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin (1955), No. 159.

Methods of picketing: a. Picketing a gentle horse; b. Picketing a lively horse

2 September 1805: “Several horses fell, some turned over and other slipped down . . . . one horse crippeled & 2 gave out . . .”

9 September 1805: “Two of our horses gave out, pore and too much hurt to proceed;” one, carrying Clark’s desk and trunk “turned over & roled down a mountain for 40 yards.”

19 September 1806: “one of our horses fell backward and roled about 100 feet down . . . & dashed against the rock in the creek, with a load of ammunition . . . did not get damaged . . .” Lewis added “this was the most wonderful escape I ever witnessed.”

22 September 1805: Clark’s “young horse in fright threw himself & me 3 times on the side of a steep hill and hurt my hip much.”

30 June 1806: Lewis’s horse “on the steep side of a high hill . . . sliped with both his hinder feet out of the road and fell, I also fell off backwards and slid near 40 feet down the hill . . .”

Other horse mishaps in June and July 1806 resulted in serious injuries for John Colter, John Thompson, John Potts, Toussaint Charbonneau and George Gibson.

Stragglers and strays

The journals record at least 30 different dates when one or more of the men thrashed around in the wilderness, apart from the group for untold hours looking for missing mounts, lost, strayed or stolen—not infrequently separated for two or three nights at a time. Forward movement of the party was delayed while men and animals were unaccounted for, always a major concern for a military commander.

A maddening number of these delays resulted from carelessness and lack of discipline, and occurred when time was of the essence. Stuck in the mountains 18 September 1805 with little water and no food (except the last of a killed colt and the portable soup) the captains were intent on hurrying on “to the level country” where the hunters could find game. Lewis directed:

the horses to be gotten up early being determined to force my march as much as the abilities of our horses would permit.

But Private Alexander Willard had failed to attend to one of his mounts which could not be found. The early morning march had to be scratched while Willard was sent back in search of his loss. He did not rejoin the party until 4 p.m., still without the horse—hardly a morale boost for his weary companions, then encamped on the side of a steep mountain after a rugged 18-mile march, and one less horse to help.

Charbonneau caused a similar delay during the eastbound trip. In the bare plains of the upper Columbia, the captains were anxious to make a “timely stage” which was then all-important to get beyond the semi-desert. Lewis wrote on 23 April 1806:

at day light . . . we were informed that the two horses of our Interpreter Charbono were absent; on enquiry it apeared that he had neglected to confine them to picquts [i.e. tied by the leg(s) to stakes in the ground] as had been directed last evening . . . .

Searching for the missing animals, two men along with Charbonneau were diverted several hours; only one of the horses was found, and the party could not get moving until 11 a.m.—a misfire for Lewis’s “timely stage.”

Charbonneau caused a second such misfire four days later, 27 April 1806. “This morning we were detained until 9 A.M.” Lewis wrote, “in consequence of the absence of one of Charbono’ s horses.”

These derelictions in April 1806 were cruel punishment for the corps. “We had not a sufficiency of horses to transport our baggage,” Clark wrote on 19 April 1806—a biting comment on the same date when Willard became at least a two-time offender. He had “suffered . . . [his horse] to ramble off.” This inattention was a last straw for Lewis. “I reprimanded him more severely for this peice of negligence than had been usual with me.”

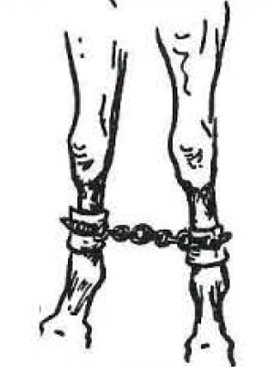

During spring time the horses were “extreemly wrestless.” Lewis recorded that they:

required the attention of the whole guard through the night to retain them, notwithstanding they were hubbled and picquted. they frequently throwed themselves by the ropes by which they were confined. All except one were stone horses [i.e. uncastrated] for the people in this neighborhood do not understand the art of gelding them, and this is a season at which they are most vicious.

The hobbling and picketing didn’t always work.[12]See the Oxford English Dictionary for distinction between these terms: picket: to tether (i.e., by rope, cord or other fastening) a horse, etc. to a picket or peg fixed in the ground; hobble: to tie … Continue reading On 2 May 1806, the party could not start moving until 1 :30 p.m.—courtesy of a steed which had been obtained from a Chopunnish man along the route. This animal had just been separated from the other Chopunnish horses the previous day. To prevent escape to rejoin its fellow creatures the captains had it “securely hubbled both before and at the side” [i.e. the front legs were tied together by rope, with further lines tying the front to the hind feet]. The horse “broke the strings in the course of the night and absconded.” Lewis sent out several men on a search party but had to resort to hiring a young Indian who found the animal 17 miles away headed for its former master.

To calm things down, the captains finally resolved to castrate these frenzied animals. George Drouillard was given the job on 14 May 1806, but botched it in part, at least when compared with Nez Perce methods. Lewis wrote on 23 May 1806 that the horses “cut by the indians will get well much soonest and they do not swell nor appear to suffer as much as those cut in the common way.”[13]1f the captains did indeed carry with them Ephraim Chambers’ Cyclopedia: or, An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Science . . . with the supplement and modern improvements incorporated in one … Continue reading Lewis’s own horse was a victim of this operation, “being much reduced and . . . in such an agoni of pain that there was not hope of recovery” and had to be shot on 1 June 1806.

Grazing Horses on Alice Creek

© 2015 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Lewis led a group on horseback through this valley before climbing present Lewis and Clark Pass, on the back to the Great Falls of the Missouri.

—Kristopher Townsend, ed.

Once east of the Continental Divide, the party was acutely vulnerable to native theft and piracy. But strangely enough, security measures (such as picketing, hobbling, night sentinels, etc.) became lax and indifferent. The captains proclaimed firm resolve for heightened security, but alongside their rhetoric disastrous thefts occurred. Three conspicuous examples follow.

Clark to the Yellowstone

Homeward bound for the Yellowstone route, Clark with 49 horses on 5 July 1806 observed “fresh sign of 2 horses and a fire burning on the side of the road” which he presumed was evidence of native spies nearby. The very next day he discovered that nine of “the most valuable horses we had” had been stolen during the night. Closing the barn door, so to speak, after this loss, he directed that “the rambling horses should be hobbled and the sentinel to examine the horses after the moon rose.” But again a few days later Clark noted further Crow smoke signals, on 18 July 1806 and 19 July 1806, which appeared again to be a possible hostile warning. He woke up two days later to news that “Half of our horses were absent.” Once more, ex post facto, he wrote “I deturmined to have the ballance of the horses guarded . . . .”

Sgt. Pryor’s Mission

Having lost at least 29 horses to thieves, just when ready to resume river travel, Clark placed the remaining horses in custody of Sgt. Nathaniel Pryor and three companions to take them overland to the Mandan, intending them to be traded there for the further needs of the Corps on the final homeward leg (see Pryor’s Mission). Despite the warning lessons with Clark, Pryor’s security was similarly deficient. On the second night after leaving Clark, all of his horses were stolen. Pryor reported having discovered tracks of the thieves within 100 paces of his camp! Clark’s contingent thus became utterly destitute: “we have now no article of Merchandize, nor horses to purchase with.”

Lewis to the Great Falls

Lewis also, on his separate mission toward the Great Falls and the upper Marias River, was aware of the presence of nearby raiding parties. He noted on 6 July 1806 that his party was “much on our guard both day and night.” But the guard was not good enough. On the morning of 12 July 1806, he learned that “ten of our best horses were absent,” three of which were recovered. Drouillard, perhaps the most versatile and valuable member of the party, was absent three days searching for the missing horses. Lewis became deeply anxious over his possible ill fate, thinking a grizzly bear had killed him. When Drouillard finally had safely rejoined the party, Lewis wrote: “I felt so perfectly satisfied that I thought but little of the horses although they were seven of the best I had . . . .”

This theft resulted in a reduction of the planned Marias scouting party—with extremely dangerous consequences erupting in the Blackfeet confrontation just two weeks later.[14]The author is indebted to Arlen Large for citing the serious operational consequences of this theft. In letter to the editor dated 7 June 1994, Large noted that Lewis “originally had planned to … Continue reading

During these few weeks of July practically the entire stock had been stolen away. How to account for this hemorrhaging? Was it failure of military discipline in maintaining security? Or lack of know-how in controlling restive animals? Or simply professional expertise of the thieves?[15]See Vernam, 210-11 for discussion of horse stealing as “the highlight of Indian existence” which “must not be judged by the precept of the white man’s Eighth Commandment . . . … Continue reading These losses, seemingly due to negligence, must have been devastating to the captains—finding their vital investment, so laboriously and expensively acquired, suddenly disappear in the night.

Some of the ways in which the Corps contrived to preserve the investment in horses are listed below:

| Threat | Response |

|---|---|

| Theft | Animals left with Nez Perces were branded;[16]Milo M. Quaife, ed., The Journals of Captain Meriwether Lewis and Sergeant John Ordway . . . (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Collections, 1916), vol. XXII , 293. John Ordway‘s … Continue reading the two expedition horses going up the Missouri were apparently taken on board the keel boat at night.[17]Paul Russell Cutright, A History of the Lewis and Clark Journals (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976) 234-35, quoting Private Whitehouse’s paraphrased journal entry of 10–11 June 1804. |

| Animal Restiveness | Castrating rambunctious males, picketing and hobbling; corraling; impoundments and posting of night sentries generally effective on westbound trip (but see above for failed measures eastbound). |

| Slipping on ice | Shields, the blacksmith, shoed horses at Fort Mandan. |

| Sore hooves | Clark on the Yellowstone put “mockersons” made of green buffalo skins on the horses’ feet. |

| Food, water, and fatigue | Pace of the journey and camp sites had to be adapted to availability of pasture and need to rest tired animals; the captains were surprised at Mandan that local horses spurned bran meals and would eat only cottonwood bark “usually given them by their Indian masters in the winter season.” |

| Sore backs | Often “in a horrid condition,” the horses’ backs had been wounded by “illy constructed” saddles and too hard riding by their native masters. Sgt. Gass obtained “goats hair to stuf the pads of our Saddles.” |

| Overuse | The captains “apportioned the horses to the several hunters in order that they should be equally rode,” thereby preventing any horse “being too constantly hunted.” |

| Mosquitoes | Clark’s party kindled large fires—their horses stood in the smoke to avoid the torture. |

Acquiring horses and adapting to threats against them was a constant challenge. High and low points in the morale of the expedition had been linked with horses—joy and revival on finding them at the Shoshones in August 1805, but pain and humiliation on losing them in the plains in the summer of 1806. The expedition’s experience echoes a saying attributed to the Omaha Indians: “A horse you may possess but never own.”[18]Vernam, 216.

It was a saying which Chief Blackbird of the Omaha must have known. And indeed it was the figure of Blackbird which had earlier dramatized to Lewis and Clark the intimate bond between man and horse in the West, a bond expressed in burial customs observed among numerous nations along the route. On Blackbird’s death in 1800, his followers had “buried him according to his wishes, sitting erect on a horse on top of a high hill overlooking the Missouri so that he might ‘watch’ the river traffic below.[19]Roy E. Appleman, Lewis & Clark, Historic Places Associated with Their Transcontinental Exploration (1804-06), (Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, … Continue reading Lewis and Clark had visited this site (near present day Macy, Nebraska) on 11 August 1804 and decorated it with flags.

Returning there on their homeward journey in 1806, as they swept downstream below that bluff, might they have recollected their own vivid ties with horses, back in the “turrible mountains”—how horses had made the difference between success and failure, life and death? . . . . A sobering reflection—which inevitably brings to mind once again the Tennessee wilderness of October 1809 when Meriwether Lewis rode alone on the Trace, while his companion stayed behind searching for two missing horses.

Notes

| ↑1 | Robert R. Hunt, “Hoofbeats & Nightmares: A Horse Chronicle of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Parts I and II,” We Proceeded On, Volume 20, No. 4 (November 1994) and Volume 21, No 1 (February 1995), the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. Editorial additions include page titles, side headings, and graphics to assist the web-based reader. The original printed format is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol20no4.pdf#page=4 and lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol21no1.pdf#page=4. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), vol. l, 4n. |

| ↑3 | Ibid, vol. 2, 467–68. |

| ↑4 | Glenn R. Vernam, Man on Horseback (New York: Harper & Row, Inc., 1964), ix. |

| ↑5 | Gary E. Moulton, ed. The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991), vol. 7, 325. All quotations or references to journal entries in the ensuing text are from Moulton, Volumes 1–8, by date unless otherwise indicated, without further citations in these notes. |

| ↑6 | Ibid, vol. 8, 388 et seq. |

| ↑7 | Jackson, vol. 1, p. 12. |

| ↑8 | John P. Foley, ed., “Horses, Effect on Men” in The Jefferson Cyclopedia, A Comprehensive Collection of the Views of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1900), 398. |

| ↑9 | Jackson, vol. l, 92. |

| ↑10 | See also on this site: Winter at Fort Mandan. |

| ↑11 | How many 1993 U.S. dollars would be required to equal one 1805 dollar in purchasing power? An “impressionistic” comparison can be calculated from tables published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), U.S. Department of Labor, Consumer Price Indexes (CPI). Applying the suggested formula for calculating Index changes, $861 .50 on average in 1993 would be required for the “equivalent” of one dollar in 1805, measuring “average change in prices over time in a fixed market basket of goods and services” for all urban consumers (obviously quite distinct from frontier exchanges). See Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970 (U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Sept. 1975) with BLS CPI dated 1/13/94 for All Urban Consumers 1913–1993. |

| ↑12 | See the Oxford English Dictionary for distinction between these terms: picket: to tether (i.e., by rope, cord or other fastening) a horse, etc. to a picket or peg fixed in the ground; hobble: to tie or fasten together the legs of (a horse or other beast) to prevent it from straying, kicking, etc. with cords or leathern straps. Cf. also Eijah Harry Criswell, “Lewis & Clark: Pioneering Linguistics,” University of Missouri Studies, vol. XV, No. 2, (April, 1940), 47–8, 64. |

| ↑13 | 1f the captains did indeed carry with them Ephraim Chambers’ Cyclopedia: or, An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Science . . . with the supplement and modern improvements incorporated in one alphabet by Abraham Rees . . . (London, 1778-86 and later)—as Donald Jackson thought possible (see Bulletin of the Missouri Historical Society, vol. 36, No. 2, Oct. 1959–Jul. 1960, 3–13)—they and Drouillard would have had available a very specific set of instructions for accomplishing the operation. This may or may not have been “the common way” referred to by Lewis. See Volume II of Chambers Article on “Gelding” which further counsels that “the wane of the moon is preferred as the fittest time.” |

| ↑14 | The author is indebted to Arlen Large for citing the serious operational consequences of this theft. In letter to the editor dated 7 June 1994, Large noted that Lewis “originally had planned to take six men with him on his reconnaissance of the Marias. With the loss of . . . horses from his herd he had to cut this escort back to three. Would the Blackfeet later have dared to mess with seven soldiers, including the leader, as they tried to do with just four?” |

| ↑15 | See Vernam, 210-11 for discussion of horse stealing as “the highlight of Indian existence” which “must not be judged by the precept of the white man’s Eighth Commandment . . . . success depended on skill, bravery, and physical prowess, being commonly rated a higher honor than killing an enemy.” |

| ↑16 | Milo M. Quaife, ed., The Journals of Captain Meriwether Lewis and Sergeant John Ordway . . . (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Collections, 1916), vol. XXII , 293. John Ordway‘s entry of 5 October 1805 states that “a stirrup Iron” [underlining added] was used to brand the 38 horses left with the Nez Perces. Wayne Williams, a longstanding member of our Trail Heritage Foundation and student of horse lore, believes that Lewis’s branding iron referred to herein could not have been used to brand horses. His opinion is in concert with that of Manfred R. Wolfenstine, in The Manual of Brands and Marks, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970), 103 who assumes that this iron (dimensions and design as illustrated) “was not used to brand animals but rather to mark bales of specimens which were sent back east wrapped in hides.” The brand may be too large for branding horses; it is also too intricate in design and manufacture to be considered as having been forged en route by Private Shields, the expedition blacksmith. Though not listed in the inventory, the iron must have been part of the freight accompanying the party on debarking from Camp Dubois in May 1804—that ‘stirrup irons’ (as designated by Sgt. Ordway) were used on the early frontier for horse branding is attested in Journal of an Exploration in Spring of the Year 1750 by Dr. Thomas Walker, preface by William Cabell Rives (Boston: Little Brown & Co., 1888), 51; entry for 30 April 1750 refers to a horse branded by “a swivel stirrup iron.” |

| ↑17 | Paul Russell Cutright, A History of the Lewis and Clark Journals (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976) 234-35, quoting Private Whitehouse’s paraphrased journal entry of 10–11 June 1804. |

| ↑18 | Vernam, 216. |

| ↑19 | Roy E. Appleman, Lewis & Clark, Historic Places Associated with Their Transcontinental Exploration (1804-06), (Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1975, Second Printing 1993), 93–4. |