Something to Boot

A Knife to Boot

Photo © 2014 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

As Meriwether Lewis got ready to lead his men back over the Bitterroot Mountains toward home on 13 June 1806, he reported in his journal a small commercial transaction with a local Nez Perce Indian, who:

exchanged his horse for one of ours which had not perfectly recovered from the operation of castration and received a small ax and a knife to boot . . . .

Americans today still use that trading expression, “to boot,” meaning an addition, a bonus, something extra thrown in. It’s interesting to know the term was current in 1806, but in fact it then was already hundreds of years old. The medieval English word bote signified a tenant farmer’s right to help himself to the manor’s wood supply to repair his own hedges and fences (haybote) or his house (housebote). This perquisite, giving the farmer a benefit beyond his share of the manor’s crops, evolved into the idiomatic “something to boot” available to speakers of American English in the early 19th century to describe a generous swap.[2]Ciardi, John, A Browser’s Dictionary and Native’s Guide to the Unknown American Language (New York: Harper and Row, 1980), 36.

The Journals as Linguistic Archaeology

The journals of the Lewis and Clark expedition were written in the direct workaday language of the times, except when Lewis self-consciously shifted gears into fancy rhetoric to describe some spectacle like the Great Falls of the Missouri. Mostly it was we-did-this, and we-did-that, in the spare vocabulary of the busy traveler, spiced here and there with the clichés and colorful sayings of the time. That vocabulary itself is another valued legacy of the 1804–1806 expedition, because it amounts to a sort of linguistic archaeological record of some of the expressions then current in American English.[3]The expedition journals “are amazingly rich in terms actually used by the hardy backwoodsmen who carried the torch of civilization across the American continent and made of it the home of a … Continue reading

These terms could be quite old, like “to boot,” and “nag,” a slang descendent of the Middle English nagge, for a small horse or pony, used by Lewis to describe the next Indian horse he would ride.[4]Partridge, Eric, Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1966), 425. But it should be remembered that the expedition leaders were with-it young officers fully attuned to contemporary events. Fresh from his job at Thomas Jefferson‘s White House, Lewis for example was familiar with the word “parachute,” newly coined for a novel aerial device making headlines for daredevil balloonists in Paris and London. The captain borrowed that new word to help report a discovery in Great Plains botany.

The Hen-wives‘ Dommanicker

The great strength of the English language has been its easy incorporation of new expressions into its original Indo-European and Germanic framework. The hybrid result includes folk sayings that survive because English speakers over the centuries have found them particularly apt. In his book A Hog on Ice, and Other Curious Expressions, Charles Earle Funk noted that Americans still “are using phrases and sayings in our common speech which hark back to the days of the Wars of the Roses and the House of Tudor.”[5]Funk, Charles Earle, A Hog on Ice and Other Curious Expressions (New York: Harper and Row, 1985), 15.

Without worrying about the source, Lewis found it natural to use one such term to describe the heart stopping upset of the expedition’s white pirogue on the Missouri on 14 May 1805. The squall of wind that struck the vessel, wrote Lewis, “would have turned her completely topsaturva, had it not been from the resistance made by the oraning against the water.” The captain was using his own phonetic version of “topsy-turvy,” denoting something turned upside down. Charles Earle Funk said this term was “coined for this purpose over four hundred years ago, and has the literal meaning of “top turned over.”[6]Funk, Charles Earle, Horsefeathers and Other Curious Words (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1958), 216.

The Journals as Linguistic Archaeology

Although it normally outweighs a spruce grouse by as much as five or six pounds, one can see why Lewis thought of the Dominique chicken when he saw the spruce grouse.

Some hoary English words rooted in late medieval agriculture were still in use in Lewis and Clark’s day, but now are fossils in urban America. In Oregon Lewis described on 23 March 1806, a “pheasant’ (actually a grouse) which he said resembled “that kind of dung-hill fowl which the hen-wives of our country call dommanicker.” The massive 12-volume Oxford English Dictionary, a respected tracer of word origins, records the word “henwife” (a woman who has charge of fowls) was in print as early as the year 1500.[7]The Oxford English Dictionary, 12 Vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1933), 5:224.

Living in Clover at Fort Clatsop

Some of the captains’ expressions were not quite so old. At Fort Clatsop on 11 March 1806, the party experienced a rare abundance of good things to eat—fresh sturgeon, anchovies, potato-like wapato roots—and Lewis reached for the first cliche that came to mind: “we once more live in clover.”

The meaning was obvious to people much more familiar with the ways of livestock than we are today; clover is what’s eaten in cow heaven. Yet the Oxford English Dictionary could find no printed use of the smug living-in-clover expression until 1710—less than one hundred years before it reached Fort Clatsop.[8]OED, 2:531. “We nooned it”—a frequent journal expression for the party’s midday break for dinner—was another relatively recent hayfield transplant traced by one lexicologist to the farmers of upper New England.[9]Ciardi, 274.

Land of the Living

A culinary windfall also produced a well-worn expression from William Clark, hungry after the rigors of the Lolo Trail on the way home. When the expedition’s hunters lugged twelve deer back to camp at Travelers’ Rest on 1 July 1806, Clark reported: “this is like once more returning to the land of the liveing a plenty of meat and that very good.”

“Land of the living” is one of the many Biblical allusions woven through the English lexicon by people more familiar with the Scriptures than many are today. According to Eric Partridge in his Dictionary of Clichés, the expression comes from Jeremiah 11:19: “Let us cut him off from the land of the living, that his name be remembered no more.” In Partridge’s opinion, the expression didn’t achieve the grooved-speech status of a cliché until late in the 18th century.[10]Partridge, Eric, A Dictionary of Clichés (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1978), 116.

Driven into Coventry

Lexicologists aren’t always so sure about the origin of some expressions, even if the meaning is clear. Someone being shunned by society is “sent to Coventry,” and Lewis thought that was an apt description of the temporary confinement of Nez Perce women during menstruation. On 9 May 1806, he reported seeing a small hut used as “the retreat of the tawney damsels when nature causes them to be driven into coventry.” How did an ancient city in the English midlands become a symbol of social banishment? The slang dictionaries say “origin uncertain.” Even the Oxford English Dictionary is cautious, venturing that a “probable suggestion” of banishment is found in a 1647 reference to the confinement of Royalists in Coventry’s jail during the English Civil War.[11]OED, 2:1102.

A Germanic Waylay

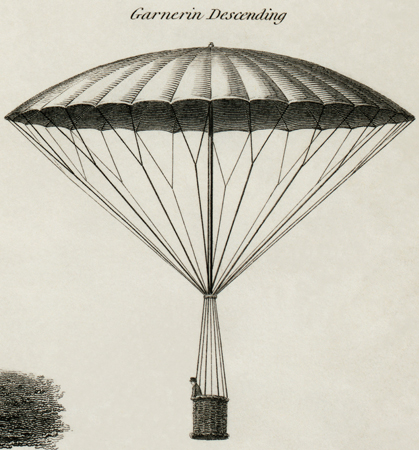

Garnerin Descending (Detail)

Drawn by Joseph Clement. Engraved by Ambrose William Warren (1781?–1856) & J. Davis. Digitally cropped, repaired, cleaned, and brightened.[12]Aeronautics (London: Rest Fenner, Paternoster Row, 1818). Available at the Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002722696/ accessed on 3 January 2018. This image is in the public … Continue reading

As early as 1802, a parachute jump was made in London by a French balloonist, Andre-Jacques Garnerin.

Like ours, the language of Lewis and Clark was rich in expressions not native to Mother England. English is a Germanic tongue, as seen in Lewis’s story of Private John Collins and the bear. Moving back up the Columbia River on the way home, the exploring party’s hunters had killed a bear, and Collins found three deserted cubs in the den of another. The private, wrote Lewis on 4 April 1806, “requested to be permitted to return in order to waylay the bed and kill the female bear; we permitted him to do so.” “Waylay” may sound like common English, but it’s derived from the Middle German wegelagen, to lie waiting for someone on the road.[13]Partridge, Origins, 733.

A French Cap-a-pie

The previous summer, Lewis had occasion to use a term imported from medieval France. At first the captain thought he might have been too successful in his long search for the Shoshones at Lemhi Pass; galloping toward him came the warriors of Cameahwait’s whole band “armed cap a pie for action.” The expression “cap-a-pie” isn’t often heard in English these days, but it means someone decked out from head to foot, as tipped off by the Latin roots caput and pedem.[14]Partridge, Origins, 226.

Cottonwood Parachutes

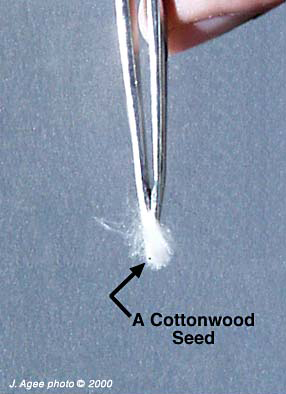

Cottonwood Seed

© 2000 by J. Agee.

The cottonwood‘s fruit ripens until the pods, now dry, burst like popcorn, presenting their seeds for the wind to distribute.

The expedition’s most interesting import was “parachute,” a coined word just entering both French and English. For centuries inventors, including Leonardo da Vinci, had fiddled with designs for umbrella-like devices that would let someone float down from a height. In December 1783, a physics professor named Sebastian Lenormand jumped off a tower at Montpellier, France, beneath a cone-shaped cloth canopy. Not only did Lenormand survive a hard landing, but he was credited with assembling a new word for his device from the Greek root “para,” to prevent or ward off, and “chute,” French for fall. Linguistically, a parachute thus wards off a fall in the same way that a parasol wards off the sun. The year 1783 also saw two men ascend over Paris in a hot-air balloon, and that soon set off a round of experiments in dropping balloon-borne dogs and sheep over the side in parachutes. The French stuntman, Jean-Pierre Blanchard, wowed Federal government officials with America’s first manned balloon ascension over Philadelphia in January 1793, followed in a few days by the parachute drop of a dog, cat, and squirrel. In October 1797, Andre-Jacques Garnerin was the first man to parachute successfully from a balloon, as Parisian ladies fainted, and he repeated the feat over London in 1802.[15]Lucas, John, The Big Umbrella (New York: Drake Publishers, 1975), 2–13.

These sensational events were of course being reported in American newspapers. So as Lewis catalogued his botanical specimens collected during the trip up the Missouri River in 1804, he had a useful new word for describing a peculiar fluffy object:

this specimine is the seed of the Cottonwood which is so abundant in this country, it has now arrived at maturity and the wind when blowing strong drives it through the air to a great distance being supported by a parrishoot of this cottonlike substance which gives the name to the tree.[16]Moulton, Gary, ed. The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1987), 3:452.

The spelling was original, but Lewis was precise in both the pronunciation and meaning of the new word. Technology is still contributing new terms, like “chopper” and “blastoff,” to English speech, while imports like “pizza” and “kamikaze” continue to flow in from foreign tongues. As did Lewis and Clark, Americans today can still call on the ancient words of Old England to express themselves, with many rich expressions from other sources to boot.

Notes

| ↑1 | Arlen J. Large, “Writing in Clover: The Versatile Vocabulary of Lewis and Clark,” We Proceeded On, Volume 13, No. 4 (November 1987), the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. Editorial changes include the title, adding the sub-headings, and adding graphics. The original printed article is can be found at https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol13no4.pdf#page=12. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ciardi, John, A Browser’s Dictionary and Native’s Guide to the Unknown American Language (New York: Harper and Row, 1980), 36. |

| ↑3 | The expedition journals “are amazingly rich in terms actually used by the hardy backwoodsmen who carried the torch of civilization across the American continent and made of it the home of a nation,” wrote Elijah H. Criswell, Lewis and Clark: Linguistic Pioneers, University of Missouri Studies (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1940), XV:2, vii. Criswell identified hundreds of expedition terms not listed in contemporary dictionaries, including such new animal names as prairie dog and mule deer, and a “humorous coinage” by Lewis, dismorality of order in the abdomen, meaning an upset stomach. |

| ↑4 | Partridge, Eric, Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1966), 425. |

| ↑5 | Funk, Charles Earle, A Hog on Ice and Other Curious Expressions (New York: Harper and Row, 1985), 15. |

| ↑6 | Funk, Charles Earle, Horsefeathers and Other Curious Words (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1958), 216. |

| ↑7 | The Oxford English Dictionary, 12 Vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1933), 5:224. |

| ↑8 | OED, 2:531. |

| ↑9 | Ciardi, 274. |

| ↑10 | Partridge, Eric, A Dictionary of Clichés (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1978), 116. |

| ↑11 | OED, 2:1102. |

| ↑12 | Aeronautics (London: Rest Fenner, Paternoster Row, 1818). Available at the Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002722696/ accessed on 3 January 2018. This image is in the public domain (in the United States). |

| ↑13 | Partridge, Origins, 733. |

| ↑14 | Partridge, Origins, 226. |

| ↑15 | Lucas, John, The Big Umbrella (New York: Drake Publishers, 1975), 2–13. |

| ↑16 | Moulton, Gary, ed. The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1987), 3:452. |