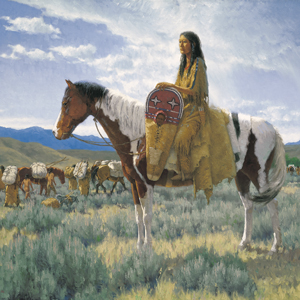

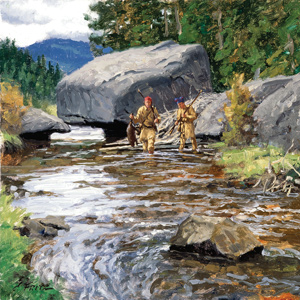

Lewis and Clark Meeting Indians at Ross’ Hole

by Charles M. Russell (1864–1926)

Reproduced by permission of the Montana Historical Society.

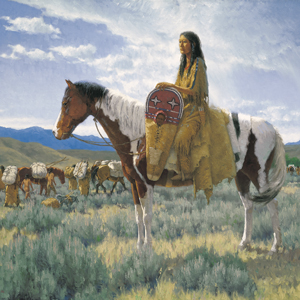

Toby, the name given by Lewis and Clark to the Lemhi Shoshone guide who took them across the Bitterroot Mountains on their journey to the Pacific, was one of the more important, if enigmatic, of the many Native Americans who assisted the explorers on their epic trip. Toby spent a total of 50 consecutive days with the Corps of Discovery—from 20 August 1805 to 8 October 1805—more than any other Indian except Sacagawea. He guided William Clark on his reconnaissance of the Salmon River and took the entire party over the Lost Trail Divide and down the Bitterroot River to Travelers’ Rest. From there he helped the explorers cross the Bitterroot Mountains on the snowbound Lolo Trail, a grueling 12-day passage that exposed them to bitter cold and near-starvation. Gary Moulton, editor of the Lewis and Clark journals, echoes other historians when he says that Toby “deserves considerable credit for the success of the expedition.”[2]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), Vol. 5, p. 131n. All quotations or references to journal entries … Continue reading

Gave Brains to the White Man?

The Corps’ journal keepers only once referred to Toby by name, and that was during the return trip, more than seven months after they had parted company with him.[3]Ibid., Vol. 7, p. 248. Lewis’s entry for 12 May 1806, refers to “our old Guide Toby.” Journal keeper Sergeant John Ordway also mentions him by name in his entry for 4 May 1806. … Continue reading Otherwise he appears in the journals as “our guide,” or variations thereof.[4]See, for example, Clark’s entry for 27 September 1805, “our Shoshonee Indian Guide,” and 9 October 1805, “our old guide.” John Rees, a trader who lived among the Shoshones in the 1870s, believed his real name was Pi-keek queen-ah, or Swooping Eagle. Rees also suggested that “Toby” might be a contraction of Tosa-tive koo-be, which literally translated from Shoshone means gave “brains” to “the white white-man.” According to this explanation, the name alludes to Toby’s knowledge of the terrain, and to race—a “white” white man being a Caucasian like Lewis or Clark, as distinguished from a “black” white man like York, Clark’s African-American slave.[5]John E. Rees, “The Shoshoni Contribution to Lewis and Clark,” Idaho Yesterdays, Summer 1958, pp. 2-13. Rees renders the Shoshone translation “furnished white white-man … Continue reading Perhaps Old Toby was a pet name the explorers gave him retroactively during the gloomy winter they spent at Fort Clatsop, after reaching the Pacific.

Whatever they called him, the old guide entered their lives on the morning when Clark and a small advance party arrived at the Shoshone village on the Lemhi River, west of the Continental Divide.[6]Clark’s group included Cameahwait and most of the other Indians who had been with the party at Camp Fortunate. Also in the party were Toussaint Charbonneau and his wife, Sacagawea, acting as … Continue reading They had left Lewis and the main party at Camp Fortunate, east of the Divide, two days before, on 18 August 1805. Clark’s mission was to determine the best route to the Pacific.

Exploring the Salmon River

Cameahwait ruled out the Salmon as a way to the Pacific because of its rapids and canyons, which precluded travel either by boat or on horseback; he said that a better, but still difficult, route was the one taken by the Nez Perce Indians over the Northern Nez Perce Trail, whose eastern approach was reached via the Bitterroot Valley.

It was Clark who settled the question of whether the Salmon River offered a practical route through the mountains. On the afternoon of 20 August, after exchanging some presents with the Indians, he set off down the Lemhi Valley with Toby, ten men, and two horses.[7]Pierre Cruzatte was ordered to remain and catch up after negotiating for a third horse. Accompanied by Cameahwait and other mounted Shoshones, Charbonneau and Sacagawea returned to Camp Fortunate to … Continue reading The next day they arrived at the junction of the Lemhi and Salmon (which Clark called Lewis’s River), at the site of present-day Salmon, Idaho. Continuing down the Salmon, they arrived on the 22nd at a Shoshone fishing camp at the mouth of a tributary entering from the north. Clark called this tributary Fish Creek; on today’s maps it appears as the North Fork of the Salmon. He found several Indian families catching and drying salmon. The sight of white men “allarmed them verry much” until Toby, who had been a bit behind, caught up and reassured them that the strangers meant no harm. Toby also pointed out to Clark that an Indian road passed up the North Fork; this would be the route that, ten days later, the corps would start on during its trek over the mountains.[8]Moulton, Vol. 5, pp. 146 and 148n. Clark’s entry states that “a road passes up” the creek & over to the Missouri.” As discussed later in the text of this article, the … Continue reading The party exchanged trinkets for some fish and berries and moved downstream another three miles before halting to make camp.

Pushing on they came today’s Squaw Creek. Paralleling it was a trail that according to Toby cut off a “considerable bend” that the Salmon made to the south.[9]Moulton., pp. 154 and 157n. See also Elliott Coues, ed., The History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, 3 volumes (New York: Dover Publications, 1965; reprint of … Continue reading The little group followed the trail up Squaw Creek for six miles, then climbed a steep overlook offering a spectacular panorama to the west. From this vantage point Clark could see downstream for 20 miles as the Salmon passed through an endless expanse of mountains. In Lewis’s words, what Clark saw left him “perfictly satisfyed as to the impractability of this rout either by land or water.”[10]Clark’s westernmost point in his reconnaissance of the Salmon River put him about three miles upstream from present-day Shoup, Idaho. Much of this region remains a primitive, roadless … Continue reading

Clark’s reconnaissance lasted four days and took him 52 miles downstream from the Salmon’s junction with the Lemhi.[11]Coues, Vol. 2, pp. 533-534. Toby passed muster as a guide and proved his worth in other ways, too, by negotiating for fish and berries with several Shoshone families encountered along the way and by helping retrieve the horses one morning after they strayed during the night. As Lewis later noted in his journal, Toby appeared to be “a very intelligent old man” who “much pleased” Clark.[12]Moulton, Vol., 5, p. 138. Entry for 21 August 1805. Again, Lewis must have written this entry retroactively, after talking with Clark following the latter’s return from his Salmon River … Continue reading

Over the Bitterroot Divide

The Corps of Discovery needed Toby to guide them across the Bitterroot Mountains, because they were so thickly forested, steep, and irregular. Descriptions of the eleven-day journey across the Bitterroot Mountains are particularly brief in Clark’s journal, and almost nonexistent in Lewis’s. This omission makes it difficult for the reader to discern particular segments of the journey. In some instances, the most difficult part of the corps’ journey over the Bitterroot Mountains was covered in a few short paragraphs. The most important part of the Bitterroot crossing in 1805—from Travelers’ Rest to what is known as “Wendover Ridge” is another place where the journals are also short on detail.

Nevertheless, on 13 September 1805, at a critical point in the journey, William Clark, following the direction of Shoshone guide Toby, left Lolo Hot Springs and “passed Several Springs which I observed the Deer Elk &c had made roads to.” As they travelled toward the pass, Clark observed “several roads led from these Springs in different directions, my Guide took a wrong road and led us out of our rout 3 miles.”[13]Moulton, Vol. 5, p. 203.

Anyone who has hiked in the densely wooded western mountains can understand Toby’s experience of trying to find the right trail in the web of game trails in the underbrush. Numerous animal trails lead in and out of springs and salt licks, and it would have been difficult to find the right one. As he searched, Toby may have been negotiating the differences in his language and Clark’s. Still, he was accused of “taking the wrong trail.”

Clark explains, with a hint of uncharacteristic irritation, “after falling into the right road I proceeded on thro tolerabl rout for abt. 4 or 5 miles.”[14]Moulton, Vol. 5 p. 203. Private Joseph Whitehouse explains in his journal, “We could not get along the Indian trail, for the timber had been blown down in a thicket of Pine & other trees. —We went round this falling timber, and round a hill and got into the road again.”[15]Moulton, Vol. 11, (Whitehouse), p. 314.

Following the Lolo Trail

“Lewis and Clark’s Camp at Traveler’s Rest, Lolo Creek 1805”

Edgar S. Paxson (1852–1919)

Oil on linen, 5½’ by 10′. Commissioned for the Missoula County Courthouse, Missoula County Art Collection, Missoula Art Museum. Photo © 2023 Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

In Edgar S. Paxton’s painting of a scene at Travelers’ Rest, Toby kneels beside Lewis as he questions three Nez Perces brought into camp.

At this point, the corps was following the Lolo Trail, also known as the Nez Perce Trail. This was also the trail that the Flatheads and Pend d’Oreilles followed to the fishery at the mouth of Colt Killed Creek. The Lolo Trail follows the main ridge top that separates the two rivers (the Kooskooskee or Lochsa River and the North Fork of Clearwater). The trail had various branches—Lewis and Clark came west on a route that passed by the site of the present-day Powell Ranger Station. When they returned in 1806, they were guided by Nez Perce Indians on an easier trail, the Lolo or Nez Perce Trail that proceeded directly from the high ridge route to Lolo Pass.”[16]Idaho State Historical Society Reference Series, The Lolo Trail, Number 286, August 1970, p. 2.

The expedition camped the night of 13 September 1805, at the end of the Quawmash Meadow, on Glade Creek, where the Bitterroot Mountains closed on either side. When the Corps left the Glade Creek Camp the next day they followed the trail, the Nez Perce or Lolo Trail, to the top of an east-west ridge. About two miles above the Glade creek Camp, the Nez Perce Trail diverged from the Tushepaw Trail. At this point, Toby and the corps followed the Tushepaw Trail west to a Salish fishing site.

Was Toby Lost?

Many scholars feel that Toby was lost because he didn’t take the Nez Perce Trail, which came out down at the fishery. Toby, however, most likely guided them on the southerly route to the Tushepaw fishing site because it was the only route he knew.[17]Charles R. Knowles, “Indispensable Old Toby,” We Proceeded On November 2003 p. 32. On Clark’s Salmon River reconnaissance, Toby told the captain that he had “been among these Tushepaws (Salish), and having once accompanied them on a fishing party to another river, he had there seen Indians who had come across the Rocky Mountains.”[18]Nicholas Biddle, ed., The Journals of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark, Vol. II, (Heritage Press, 1962) p. 245.

The Lolo Trail to the river was not as prominent as the Tushepaw Trail because it wasn’t used as frequently. The Nez Perce Indians followed the Lolo Trail east to hunt buffalo on the plains, but these weren’t annual trips. Alan Pinkham, Nez Perce tribal elder and cultural committee member, in a personal conversation stated, “trips East to hunt buffalo were more random.” The infrequent trips were made by “families [who] would get together to make the trips, which could last for a year or more.[19]Alan Pinkham, Nez Perce elder and cultural committee member. Personal conversation on the times and duration of tribal members going east to Montana to bunt buffalo. February 2010.

The Lolo Trail’s eastern end, as far as Wendover Creek, appears to be older than the western part, as Ralph Space observes in his book The Lolo Trail.[20]Ralph S. Space, The Lolo Trail (Missoula, MT: Historic Montana Publishing) p. 3-4. The Salish Indians—who called Lolo Creek “tum-sum-kee” or no salmon creek—traveled the Lolo Trail over the divide to the Kooskooske or Lochsa River to fish for salmon. Because of the shorter distance, the Tushepaws may have used the trail more frequently for their fishing expeditions than the Nez Perce did for their buffalo hunting expeditions.

Toby may have been a part of one of those fishing expeditions.[21]Charles R. Knowles, “Indispensable Old Toby, ” We Proceeded On November 2003, p. 32. During the winter story telling period, there was a legend told among the Salish of how, during the creation of the world, “Coyote failed to bring salmon over the divide to stock the Bitterroot.” After the tribes acquired the horse, the activity on the Tushepaw Trail may have increased, making it more visible and easier to follow. As logs fell across the trails or their filled in with brush, newer trails would result along the route.

Was Toby lost? Clark accused Toby of taking the wrong trail. Other than that, Toby didn’t hesitate in his leadership of the corps along Tushepaw Trail, which was most likely the route he knew. Toby proceeded on: there are no entries about being lost; no indications about backtracking to find the “correct” trail. If the corps had been truly lost think of the consequences. Instead, Toby led them down the Kooskooske River to Wendover Ridge. Because we don’t have a great deal of evidence about where the Lolo Trail left the ridge above the Glade Creek Camp, and because Toby told Clark that he had been on the trail to the fishery and they were on a road that led across the mountains, Toby did not seem lost at all.

Down the Clearwater River

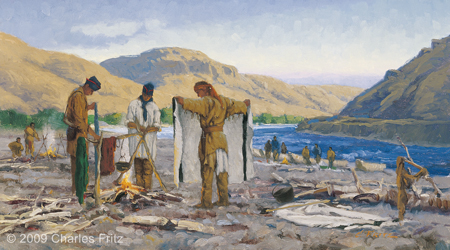

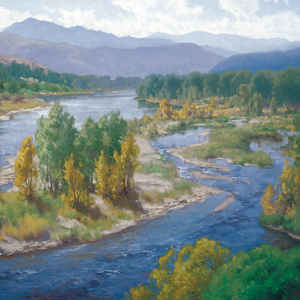

Drying Baggage Near Colter’s Creek

10″ x 18″ oil on board

© 2009 by Charles Fritz. Used by permission.

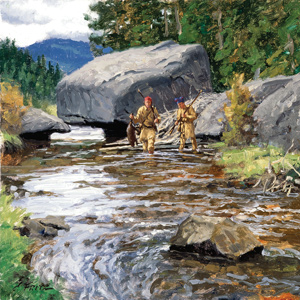

Although they apparently had little to do, Toby and his son remained with the explorers for the duration of their two-week interlude with the Nez Perce. (Clark reports on 27 September, “our Shoshonee Indian Guide employed himself makeing flint points for his arrows.”) They were still with them on 7 October 1805, when the Corps of Discovery headed down the swift-flowing Clearwater River. The explorers struggled to maneuver the ungainly and heavily burdened dugouts through the fearsome rapids. On the second day out, one of the canoes split open after hitting a rock and swamped. Its crew hung to the sides while other men worked frantically to tow the vessel ashore. Later in the day, Twisted Hair and another Nez Perce chief named Tetoharsky caught up with the expedition with the intention of accompanying it to the ocean.[22]The two Nez Perce chiefs remained with the Corps of Discovery until it reached Celilo Falls, on the Columbia. (Ferris, pp. 184-185)

For the next two nights the explorers lay to near a Nez Perce camp. They dried out the soaked baggage and were able to repair the canoe, but the near disaster and the prospect of more rough water ahead may have been too much for Toby. Sometime during the evening of 9 October 1805, he and his son slipped away to return to their people. As Gass noted, “I suspect he was afraid of being cast away passing the rapids.”[23]Moulton, Vol. 10, p. 152. The unannounced departure mystified Clark, who was concerned that Toby and his son had left without collecting their wages. When the captain asked either Twisted Hair or Tetoharsky to send a man on horseback to catch up with them, he was advised against it—Nez Perce farther upstream would simply take whatever articles Clark gave them.[24]Ibid., Vol. 5, pp. 252-253. The following spring, the captains learned from the Nez Perce that Toby and his son had commandeered two of the corps’s horses for the trek home—horses that were almost certainly more valuable than the trinkets Clark would have given them.[25]Ibid., Vol. 7, p. 248.

Indispensable Guide

Not long after the explorers returned to St. Louis, Lewis wrote a letter to an unknown correspondent describing in some detail the Corps of Discovery’s odyssey to the Pacific and back. Recounting the decision, made during their sojourn with the Shoshones, to take the route recommended by Toby, the captain told with a dramatic flourish how “we attempted with success those unknown formidable snow clad Mountains on the bare word of a Savage, while 99/100th of his Countrymen assured us that a passage was impractable.”[26]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854, 2 volumes (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), Vol. 1, p. 339. Lewis’s letter, dated … Continue reading

“Savage” or not, Toby helped the expedition over one of the roughest legs of the journey, added in other ways to Lewis and Clark’s store of geographical knowledge, and assisted them in their dealings with the Shoshones and Salish. He made mistakes on the Lolo Trail and may also have lost his way on the crossing of the Lost Trail divide, yet neither the captains nor any other journal keeper expressed (at least in writing) a negative word about him. Whether or not he actually guided them over the Lolo Trail, he was indeed indispensable.

Related Pages

Toby, the name used by Lewis and Clark for the Shoshone guide who took them across the Bitterroot Mountains on their journey to the Pacific, was one of the more important, if enigmatic, of the many Native Americans who assisted the explorers on their epic trip.

Cameahwait’s Geography Lesson

by J. I. Merritt

When Meriwether Lewis and William Clark encountered the Shoshone Indians in August 1805, one or the other—or more likely both, sat down with Cameahwait, the chief of the tribe’s Lemhi band, to learn as much as possible about the region’s geography.

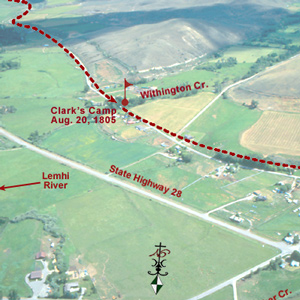

August 20, 1805

Toby shows the way

Fortunate Camp, MT and Lemhi River, ID Toby shows Clark the way down the Lemhi River. At Fortunate Camp, Lewis has a cache dug. Pack saddles are made from old boxes and oars.

August 21, 1805

Drouillard gives chase

Tower Creek, ID and Fortunate Camp, MT When a Lemhi Shoshone takes a rifle, Drouillard gives chase. At Fortunate Camp, the cache is completed and saddles and baggage are ready to be packed by horse. Clark explores the Salmon River and names it Lewis’s River.

August 24, 1805

Leaving Fortunate Camp

Salmon River, ID and Shoshone Cove, MT Lewis barters for three horses and a mule, and Charbonneau buys a horse for Sacagawea. With the help of Shoshone women, they start carrying baggage over the continental divide. Clark considers three alternate plans for reaching the Pacific Ocean.

August 26, 1805

Past the Great Divide

Lemhi River Valley, ID Having finally portaged all the baggage past the great divide, Lewis writes his last regular journal entry for the year, worried how they will cross the Bitterroot Mountains. Clark’s group moves to a Lemhi Shoshone village.

August 30, 1805

Leaving the Shoshone

Lemhi River Valley, ID The corps and their Lemhi Shoshone guides head down the Lemhi River bound for the Pacific Ocean. Clark trades his fusil musket for a horse.

The Salmon winds tortuously through a seven-mile-long canyon where the vertical walls at that time crowded the riverbanks so tightly in several places that Clark and his party were compelled to clamber over “four mountains verry Steap high & rockey.”

September 2, 1805

Leaving the Indian road

North Fork Salmon River, ID When the Corps leaves the Indian road, they must cut their own trail through brush and a “dismal swamp.” The horses stumble and fall as they cross rocky hillsides.

Continuing north up the North Fork Salmon River, they leave a good Indian road and must cut their own trail. Were they lost? Sergeant Gass’s laconic remark gives us a hint: “This was not the creek our guide wished to have come upon.”

September 9, 1805

Reaching Travelers' Rest

Travelers’ Rest, MT The expedition continues its northern route up the Bitterroot River reaching Travelers’ Rest, a well-used camping area on present-day Lolo Creek. Their Indian guide, Toby, tells them of a good pass leading to the Missouri River, and Spanish officials devise another plan to stop the expedition.

At Lewis’s right is Clark’s servant, York, dressed in blue as befitted a personal slave at that time. The Indian squatting at Lewis’s left hand is Toby, the Shoshone guide the captains had hired to lead them across the Bitterroot Mountains toward the Columbia River.

At 3 o’clock in the afternoon, 11 September 1805, Toby led the Corps of Discovery out of Travelers’ Rest camp toward the Bitterroot Mountain barrier.

September 13, 1805

Lolo Hot Springs to Packer Meadows

Packer Meadows, Lolo Trail, ID The party stops at a hot spring, and then after some difficulty finding the right trail, climbs to a divide between the Bitterroot and Lochsa River drainages. They cross Packer Meadows and encamp on Glade Creek.

By the evening of 17 September 1805, their seventh sleep west of Travelers’ Rest, it was obvious to the captains that the Indians’ assurance that they could cross the mountains in six days was false, whereas the prediction that they would find no game there was all too true.

October 7, 1805

Down the Clearwater

Lenore, ID After a busy day, thirty-three expedition members, Lewis’s dog, Seaman, and two Lemhi Shoshone guides start down the Clearwater. In the five new dugout canoes, challenging rapids test the paddlers’ skills.

October 9, 1805

Drying out at Colters Creek

Potlatch River, ID (Colters Creek) The captains decide to remain a day to dry wet items and repair a damaged canoe. Lemhi Shoshone guides Toby and his son leave unexpectedly. In Washington City, Thomas Jefferson describes several of Lewis’s specimens and lists nine animals he thinks are new to science.

Notes

| ↑1 | This article combines extracts from John Puckett’s, “Was Toby Lost?: The Shoshone Guide and the Corps in the Bitterroot Mountains,” We Proceeded On, August 2011, Volume 37, No. 3 and Charles R. Knowles’, “Indispensable Old Toby: He Led the Corps of Discovery across Lost Trail Pass,” We Proceeded On, November 2003, Vol.29 No. 4. The original full-length articles can be read at https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol37no3.pdf#page=7 and https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol29no4.pdf#page=27. Charles Knowles taught for 30 years at the University of Idaho and was a past chairman of the Idaho Governor’s Lewis and Clark Trail Committee. Knowles’ contributions to this page are the sections titled: Toby or Swooping Eagle, Gave Brains to the White Man?, Exploring the Salmon River, Down the Clearwater River, and Indispensable Guide. John Puckett is a retired forest service employee and volunteer at Travelers’ Rest State Park. His contributions to this page are the sections titled: Over the Bitterroot Divide, Following the Lolo Trail, and Was Toby Lost?—ed. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), Vol. 5, p. 131n. All quotations or references to journal entries in the ensuing text are from Moulton, by date, unless otherwise indicated. |

| ↑3 | Ibid., Vol. 7, p. 248. Lewis’s entry for 12 May 1806, refers to “our old Guide Toby.” Journal keeper Sergeant John Ordway also mentions him by name in his entry for 4 May 1806. (Moulton, Vol. 9, p. 304) |

| ↑4 | See, for example, Clark’s entry for 27 September 1805, “our Shoshonee Indian Guide,” and 9 October 1805, “our old guide.” |

| ↑5 | John E. Rees, “The Shoshoni Contribution to Lewis and Clark,” Idaho Yesterdays, Summer 1958, pp. 2-13. Rees renders the Shoshone translation “furnished white white-man brains.” Rees states, “When Clark asked his name, the Indians, instead of giving his true name, said ‘Tobe,’ meaning to convey the idea of a white man’s director.” |

| ↑6 | Clark’s group included Cameahwait and most of the other Indians who had been with the party at Camp Fortunate. Also in the party were Toussaint Charbonneau and his wife, Sacagawea, acting as interpreters; their infant, Pomp; and 11 men, including sergeants Patrick Gass and Nathaniel Pryor and privates John Collins, John Colter, Pierre Cruzatte, George Shannon, and Richard Windsor. The remaining four men cannot be identified. See Robert G. Ferris, ed., Lewis and Clark: Historic Places Associated with Their Transcontinental Exploration (1804-06) (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1975), pp. 64 and 372n. |

| ↑7 | Pierre Cruzatte was ordered to remain and catch up after negotiating for a third horse. Accompanied by Cameahwait and other mounted Shoshones, Charbonneau and Sacagawea returned to Camp Fortunate to assist Lewis’s party in crossing the Divide with the corps’s baggage. |

| ↑8 | Moulton, Vol. 5, pp. 146 and 148n. Clark’s entry states that “a road passes up” the creek & over to the Missouri.” As discussed later in the text of this article, the trail turned east, leading over what is now Big Hole Pass and down into the upper valley of the Big Hole River, whose waters flow into the Jefferson and thence to the Missouri. When Lewis and Clark reached the point where the trail turned east, they left it and continued north, thereby remaining west of the Continental Divide. |

| ↑9 | Moulton., pp. 154 and 157n. See also Elliott Coues, ed., The History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, 3 volumes (New York: Dover Publications, 1965; reprint of the 1893 edition), Vol. 2, pp. 529-535. Coues in footnote 20, p. 532, appears to confuse Berry Creek and Squaw Creek. The Berry Creek trail crosses to the headwaters of the West Fork of the Bitterroot. In 1835, the missionary Samuel Parker entered the Lemhi Valley and made his way northwest over the dividing ridge between the Salmon and Bitterroot watersheds. At least one writer has suggested that Parker followed a trail that leaves the North Fork of the Salmon above its junction with the main river and goes northwest up Hughes Creek; see Ernst Peterson, “Retracing the Southern Nez Perce Trail with Samuel Parker,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Autumn 1966. My personal knowledge of the area leads me to believe that Parker in fact traveled the Squaw Creek trail pointed out by Toby 30 years earlier. Parker’s description of the geology he saw matches the Painted Rocks formation of the upper West Fork of the Bitterroot. See Samuel Parker, Journal of an Exploring Tour, Beyond the Rocky Mountains under the Direction of the A.B.C.F.M. (Ithaca, N.Y.: Andruss, Woodruff & Gauntlett, 1844), pp. 116-117. |

| ↑10 | Clark’s westernmost point in his reconnaissance of the Salmon River put him about three miles upstream from present-day Shoup, Idaho. Much of this region remains a primitive, roadless wilderness. (Moulton, Vol. 5, p. 157n) |

| ↑11 | Coues, Vol. 2, pp. 533-534. |

| ↑12 | Moulton, Vol., 5, p. 138. Entry for 21 August 1805. Again, Lewis must have written this entry retroactively, after talking with Clark following the latter’s return from his Salmon River reconnaissance. |

| ↑13 | Moulton, Vol. 5, p. 203. |

| ↑14 | Moulton, Vol. 5 p. 203. |

| ↑15 | Moulton, Vol. 11, (Whitehouse), p. 314. |

| ↑16 | Idaho State Historical Society Reference Series, The Lolo Trail, Number 286, August 1970, p. 2. |

| ↑17 | Charles R. Knowles, “Indispensable Old Toby,” We Proceeded On November 2003 p. 32. |

| ↑18 | Nicholas Biddle, ed., The Journals of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark, Vol. II, (Heritage Press, 1962) p. 245. |

| ↑19 | Alan Pinkham, Nez Perce elder and cultural committee member. Personal conversation on the times and duration of tribal members going east to Montana to bunt buffalo. February 2010. |

| ↑20 | Ralph S. Space, The Lolo Trail (Missoula, MT: Historic Montana Publishing) p. 3-4. |

| ↑21 | Charles R. Knowles, “Indispensable Old Toby, ” We Proceeded On November 2003, p. 32. |

| ↑22 | The two Nez Perce chiefs remained with the Corps of Discovery until it reached Celilo Falls, on the Columbia. (Ferris, pp. 184-185) |

| ↑23 | Moulton, Vol. 10, p. 152. |

| ↑24 | Ibid., Vol. 5, pp. 252-253. |

| ↑25 | Ibid., Vol. 7, p. 248. |

| ↑26 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854, 2 volumes (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), Vol. 1, p. 339. Lewis’s letter, dated 14 October and written to an unknown correspondent, is very similar to a letter Clark wrote to one of his brothers on 23 September; Jackson (p. 335n) argues that Clark’s letter was actually composed by Lewis and was intended for publication in newspapers. The letter of 23 September does not include the reference to “the bare word of a Savage.” |