Barbara Fifer

George Lane photo, courtesy Helena Independent Record.

Barbara Fifer holds a degree in creative writing and comparative literature from Ohio University. As an editor and writer she has worked in many types of print media. She is the author of books that include Going Along with Lewis and Clark, Day-by-Day with Lewis and Clark, Lewis and Clark Expedition Illustrated Glossary, Meeting Natives with Lewis and Clark, Montana’s Mining Frontier Ghost Towns, Wyoming’s Historic Forts, and EveryDay U.S. Geography, and co-author with Vicky Soderberg of Along the Trail with Lewis and Clark,a highly successful book combining a lively synopsis of the Expedition’s story with travel information, plus full-color maps by Joseph Mussulman. Barbara’s credits also include articles on Western history and travel such as explanation of some Lewis and Clark place names in Montana, a biography of cowboy artist Will James, and a study of the effects of the Hard Winter of 1886-87 on the open-range cattle industry in Montana.

Contributions

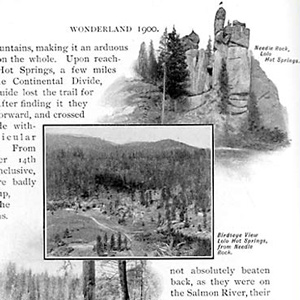

One of Wheeler’s most successful efforts to amplify any part of Lewis and Clark’s route was his exploration of the Lolo Trail. For that he relied heavily on Elliott Coues’ 1893 annotations to the expedition’s narrative.

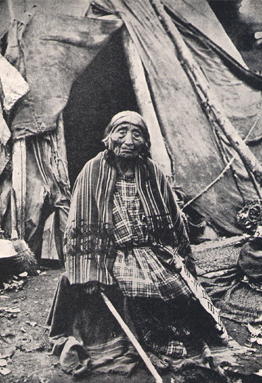

She was with the expedition for just over 16 of the 28 months of the official journey. Speaking both Shoshone and Hidatsa, she served as a link in the communication chain during some crucial negotiations. She remains the third most famous person of the expedition.

At The Dalles in 1902, a hospitable local citizen helped Wheeler make his way to the brink of the long narrow channel and chasm through which Lewis and Clark took their canoes, where he “overlooked the swirling waters as they boiled and raged.”

Salmon said, “When we come up the river we will die, so the human beings will have to catch us before that happens. I’ll come up only on certain times of the year and that’s when they’ll have to catch me.”

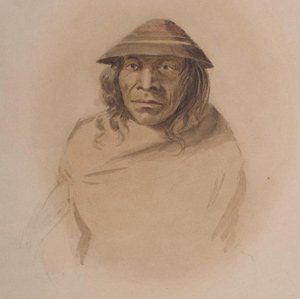

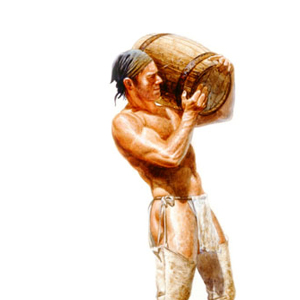

Toussaint Charbonneau

by Barbara Fifer

The fur trade had put Charbonneau in place to meet the captains and join their expedition. He was the oldest expedition member would outlive most of his fellows as he followed the rigorous life of a fur trader, guide, and interpreter.

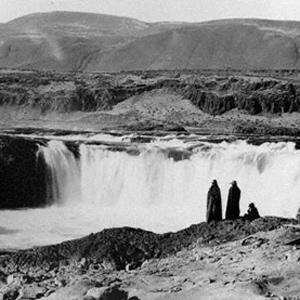

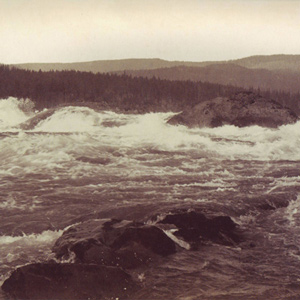

The Corps of Discovery reached a many-faceted barrier, Celilo Falls, which required a portage. The falls proved to be the beginning of fifty-some river miles that also held The Short and Long Narrows (jointly called The Dalles), and ended with the lengthy Cascades of the Columbia.

The Deschutes River

by Barbara Fifer

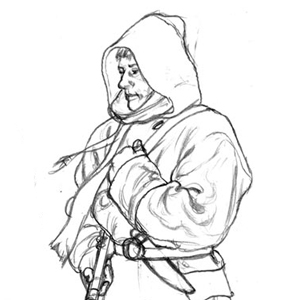

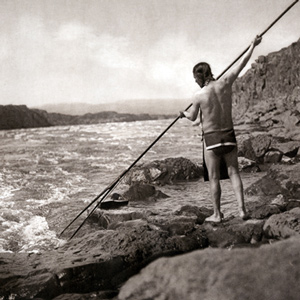

The fall salmon run was ending when the Corps arrived at the Great Falls of the Columbia, several miles below the mouth of Towarnehiooks, with some native people still at the river, fishing with gigs and nets and processing their salmon harvest.

Windsor helped recover three orphaned grizzly bear cubs of a sow they killed on a hunt in early April of 1806. According to Lewis, they traded the cubs to some coastal Indians, who, “fancyed these petts and gave us wappetoe in exchange for them.”

The Wascos and Wishrams

by Barbara Fifer

At The Dalles lived Upper Chinookan people, the Wishrams on the Columbia’s north (Washington) side—and their allies the Wascos on the south (Oregon) side—who were the main masters of the regional trading center. The Lewis and Clark Expedition encamped on the north side.

Weiser was a member of Sgt. John Ordway’s detachment that paddled the canoes back to the Great Falls. During the 1806 portage around the Falls of the Missouri, he suffered a disabling accident.

Joseph Field

by Barbara Fifer

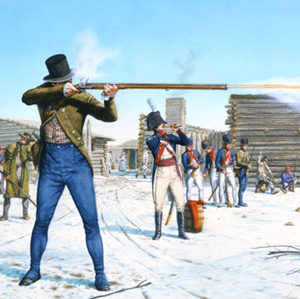

Joseph yelled to his brother Reubin, who was instantly awake, and the two sprinted for fifty to sixty paces after the natives who were clutching their guns.

In 1902, Wheeler followed the Northern Pacific’s course over Bozeman Pass and the Yellowstone River promoting both the railroad and the Lewis and Clark Centennial.

Here the Columbia was “an agitated gut Swelling, boiling & whirling in every direction.” Even so, Cruzatte and Clark agreed that they could run the canoes through.

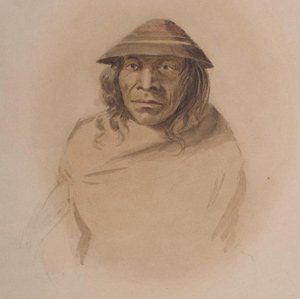

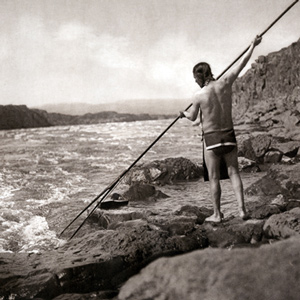

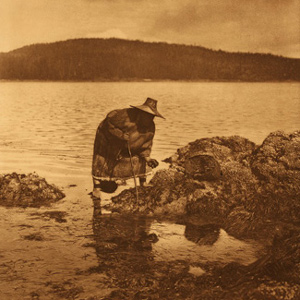

As documented by Edward Curtis

Photographer Edward Curtis himself described the processes pictured here. “In the preparation of this article of food the salmon was beheaded and gutted, and with a sharp knife the two halves were separated from the backbone and the skin.”

For John Boley, assigned to the return party, the Corps’ 1804 travels apparently whetted an appetite for frontier exploration. After reaching St. Louis on the keelboat in 1805, he volunteered for Zebulon Pike’s expedition that was to leave on August 9.

Traveling through the Marias River country with anthropologist George Bird Grinnell, Wheeler met Wolf Calf, one of the Indian survivors of Lewis’s encounter with the Blackfeet.

Two widely separated branches of Salishan languages developed prior to 1800, Coastal and Interior. Lewis and Clark encountered several nations from both of these branches.

His name appears only one time, when he is listed as a member of Corporal Warfington’s detachment bringing the keelboat back from Fort Mandan. He may not have even made it that far.

Homeward bound in April 1806, the Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled through the Columbia Gorge and pitched camps on its north side. Their passage was tense and unpleasant, with Indians taking small goods regularly.

Lewis wrote that “McNeal had exultingly stood with a foot on each side of this little rivulet and thanked his god that he had lived to bestride the mighty & heretofore deemed endless Missouri.”

Clark described the Cascades as having a “Great Shute” where the Columbia dropped about twenty feet over both large and small rocks, “water passing with great velocity forming & boiling in a most horriable manner.”

At a place where “one false Step of a horse would be certain destruction,” Frazer’s pack horse took that fateful step, lost its footing and rolled with its load “near a hundred yards into the Creek,” over “large irregular and broken rocks.”

The story Wheeler wished to tell can be found in his book’s subtitle: “A story of the great exploration across the Continent in 1804-06; with a description of the old trail, based upon actual travel over it, and of the changes found a century later.”

Including a court martial, charging grizzlies, and a mile-long swim down the Missouri River, Willard’s adventures are well-documented in the journals. He survived them all, crossing the Missouri a final time on his way to California, at age 74.

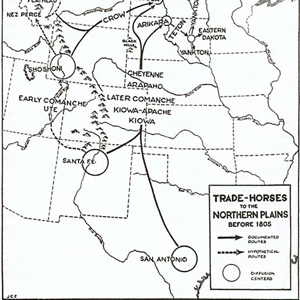

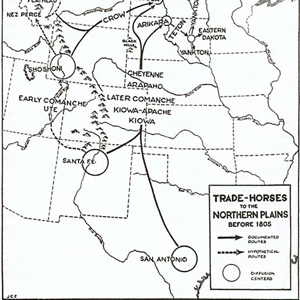

Indian Horses in the PNW

by Barbara Fifer

One of the reasons Clark had so much difficulty in purchasing horses at The Dalles in the spring of 1806 is that he was at the very northwestern edge of their dispersal across North America.

The laborer from Boston was to take the boats to the Mandan Villages and then return to Fort Kaskaskia. He may have never gotten that far.

Drouillard was one of the captains’ three most valuable hands. He was also the highest paid member after the captains, he shared the Charbonneaus’ tent with the family and the captains, and he was the only man Clark seemed to call by first name in the journals.

Colter left a legacy of western lore, not the least of which was his famous run from the Blackfeet Indians and his exploration of “Colter’s Hell.” Yet his contributions to the expedition were also many.

Sahaptian Peoples

by Barbara Fifer

From The Dalles, Sahaptian (also Shahaptian) languages extended eastward to the Rocky Mountains. Speakers of these languages met by the Corps included the Walla Wallas, Klickitats, Teninos, Umatillas, Yakamas, Wanapums, and Nez Perces.

Ordway’s journal is the only one carries an entry for every one of the trek’s 863 days. Just after the expedition ended, Ordway had purchased the land warrants issued to Jean-Baptiste Lepage and William Werner.

Starting out as a private with a specialty of carpentry, Gass was soon elected a sergeant after the death of Sergeant Charles Floyd. His was the first expedition journal to be published. He was also the last surviving member.

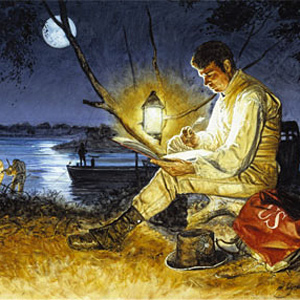

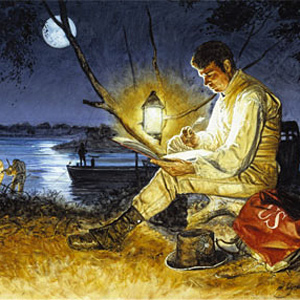

“Late at night we were awaked by the sergeant on guard to see the beautiful phenomenon called the northern light….” What did Meriwether Lewis and William Clark understand about the aurora borealis? Scientific theories of their time may sound a bit fanciful today.

Life’s Cycle at the Dalles

by Barbara Fifer

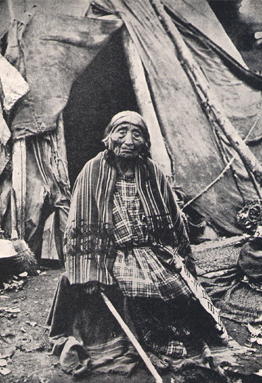

From the Columbia Plateau to the river’s mouth, people followed a yearly cycle for fishing, hunting, and harvesting wild foods. In the summer, people from many Sahaptian and Chinookan tribes visited The Dalles to trade and socialize.

Chinookan Peoples

by Barbara Fifer

The Lewis and Clark Expedition first encountered Chinookan-speaking people at the Dalles of the Columbia River. Upper and Lower Chinookan tribes were in contact as the expedition traveled to the river’s mouth, wintered at Fort Clatsop, and returned home in spring 1806.

He had gotten off to a bad start, but apparently, the captains, or at least Clark, saw something in him that was worth saving. They would name Idaho’s Lolo Creek, Collins Creek.

The Northern Pacific Railway had identified two new attractions within its Wonderland—a centennial commemoration of the historic Lewis and Clark expedition, plus extensive segments of the original trail within sight of its rails.

On 23 January 1806, Lewis dispatched Howard and Werner to the Salt Camp on the ocean beach, to bring back a supply of salt. When they had not returned by the 26th, Lewis feared they had gotten lost.

Lewis and Clark reported seeing layers of coal along the Missouri River’s northern reach. Jefferson had only to look to Great Britain, already fifty years into the Industrial Revolution, to see what was coming.

On 8 October 1805, the canoe split open and took on water. The Corps encamped for two days to dry out the goods, allowing Thompson to heal a bit.

Where Reed came from and where he went, no one knows, but as an expedition member, he lasted only until August 1804 when he deserted.

The captains sent four men to retrieve Gibson, “who is so much reduced that he cannot stand alone and…they are obliged to carry him in a litter.” They arrived on February 15, and Lewis went to work sweating the “veery languid” Gibson with saltpeter and dosing him with laudanum for sleep.

Shannon had found the horses, then “Shot away what fiew Bullets he had,” failing to get any meat. Eventually, he carved a bullet from a stick and got a rabbit–his only food other than wild grapes during more than two weeks.

Cruzatte’s skills in piloting boats were called on frequently during the expedition. As the main fiddle player, his music brought life to many a celebration. In addition, he could speak Omaha.

On 11 May 1805, Bratton appeared, running toward the river and yelling to be taken aboard quickly. He had shot a grizzly through the lungs, and the wounded bear had chased him for half a mile. The bear had lived at least two hours after first being shot.

Dame’s sole claim to notice in the captains’ journals was the fact that he shot an American white pelican at what the captains named Pelican Island, near today’s Little Sioux, Iowa.

Reubin and his brother Joseph (about a year older) were among the best hunters, but Reubin was possibly the better shot. He was, at least, at Camp Dubois on 16 January 1804, when Clark’s men set up a shooting match with some local residents.

If this plant was what Sacagawea was referring to when she told Clark she favored spending the winter anyplace where there was “plenty of Potas,” it may be that some of the men had recognized it as “duck potato” or “Indian potato.”

His journal begins, “about 3 Oclock P.M. Capt. Clark and the party consisting of three Sergeants and 38 men who manned the Batteaux and perogues. we fired our Swivel on the bow hoisted Sail and Set out in high Spirits for the western Expedition.”