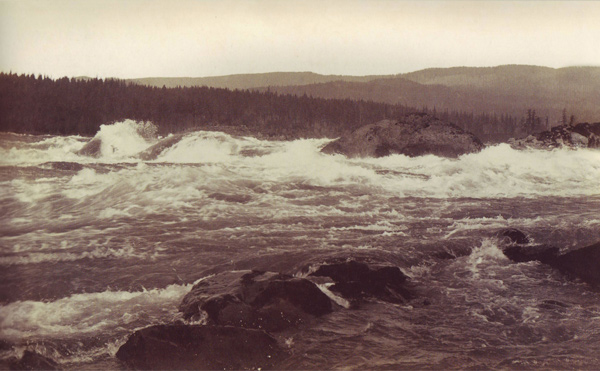

The “Great Shute”

Clark described the Cascades as having a “Great Shute” extending about one half mile, where the Columbia was 150 yards wide and dropped about twenty feet over both large and small rocks, “water passing with great velocity forming & boiling in a most horriable manner.” Then the river continued among fully and partially exposed boulders for another two miles of extreme rapids. Over the entire two-and-a-half-mile length of the Cascades, he estimated that the Columbia fell 150 feet.

Even after watching local Indians portage the Cascades’ entire length, the captains decided they could get the canoes through by ropes and a temporary log “road.” On 1 November 1805, the men carried all their baggage over a 940-yard portage, a “bad way over rocks & on Slipery hill Sides.” Then they laid poles across the exposed rocks, and let the canoes down the falls and dragged them over the rest of the rapids. Battered and needing repairs, the four canoes survived this passage.

On 2 November 1805, the Corps “Examined the rapid below us more pertcelarly” and decided to empty the canoes and have the non-swimmers walk around. They portaged their baggage for a mile and a half, then ran the Cascades’ lower rapids in the canoes: “one Struck a rock & Split a little, and 3 others took in Some water[.]” They then safely passed two more sets of rapids in the next four miles before—downstream from today’s Bonneville Dam—the Columbia became “a Smoth gentle Stream of about 2 miles wide, in which the tide has its effect as high as the Beaten rock [Beacon Rock].”

Local Indians

Of as much interest to Clark as describing the Cascades was writing about the people who lived along them. The men had pierced noses; men and women had flattened foreheads; male and female clothing comprised skimpy garments of leather (they were “nearly necked”; their clothing was labeled “indecent” on March 29, 1806); blue and white beads decorated everything. To him, these people were “durty in the extreme both in their Coockery and in their houses,” and he believed the adults’ many missing and extremely worn-down teeth came largely from eating uncleaned roots just as they came from the soil.[1]Clark made a good inference. Teeth ground down from decades of eating stone-ground grains is one way that anthropologists and archaeologists age-date ancient human remains. Had he had the time to observe the whole process of drying salmon to make fish pemmican, he would have seen that the violent Gorge winds continually blew sand into the hanging fillets, which also abraded the Indians’ teeth.[2]Emory Strong, Stone Age, 46.

Clark failed to clarify the extent of the trade between Indians and whites lower down on the Columbia, but he concluded it was of minor importance, since the Indians’ “knowledge of the white people appears to be verry imperfect, and the articles which they appear to trade mostly . . . Pounded fish, Beargrass, and roots . . . cannot be an object of comerce with furin merchants.” Pounded fish sold especially well among the coastal tribes, since the climate there was not conducive to the fish-drying processes.

The Corps continued down the Columbia in peace, having experienced no major problems during their first visit to the area. Ahead were the miserable stormy weather of the Columbia River estuary, and the winter at Fort Clatsop.

The Cascades of the Columbia

by John Mix Stanley (1814–1872)

Special Collections, K. Ross Toole Archives, The University of Montana, Missoula

John Mix Stanley Chromolithograph from Isaac I. Stevens, Reports of Explorations and Surveys, To Ascertain the Most Practicable and Economical Route for a Railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean (1855-1862), Vol. 12, Plate 44.

John Mix Stanley’s Chromolithograph

The Gorge’s final blockade in 1805 was the Cascades of the Columbia, painted by John Mix Stanley (1814-1872). He was one of the 19th century’s finest painters of the West, yet is little known today because much of his work was lost in fires during his lifetime. Beginning in 1842, he painted Indians and frontiersmen in Minnesota, in the Southwest, along the Pacific Coast, and in Hawaii. Stanley created field sketches but also pioneered using a daguerrotype camera in the field to capture native people and landscapes for paintings produced in the studio. He toured his works for public view, and issued chromolithograph prints of them. In the 1850s, he submitted 152 paintings of 43 tribes to the Smithsonian Institution, where they stayed until destroyed by fire (just after Congress had refused to purchase them). Another large group burned up with P. T. Barnum’s American Museum in New York. More of Stanley’s works that were published in Stevens’ Reports of Explorations and Surveys appear elsewhere in Discovering Lewis & Clark®.

>