Enlisted Man’s Uniform

Each of the men from the regular army who volunteered for the expedition brought along his own dress uniform,[1]Re-creation by Robert Moore, Historian at Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, St. Louis; Peyton C. Clark; Greg Hudson, Weeping Heart Trade Company, Ehrlanger, Kentucky. Photos by Jon Stealey. which was worn for formal, official occasions such as dress reviews and parades, courts martial, and funerals.

The coat of blue and red wool, lined with linen, was cheaply made, without edging or binding. The black neckpiece, or “stock,” under the red coat collar was made of leather. Twenty-two purely decorative buttons were of pewter (in those days mostly lead, with a little tin added). An infantryman was identifiable by the white “turnback” at the lower front of his coat, an artilleryman by one of red.

Hanging from the brass (an alloy of copper and zinc) buckle is a whisk used for cleaning the pan of his flintlock firearm. Each soldier would also have carried a pick to clean the touchhole, through which the flash from the pan ignited the powder in the breech of the gun.

The enlisted man’s “small clothes” were similar to an officer’s—a knee-length flannel or linen pullover shirt that was tucked between the legs inside a pair of tight-fitting white (for summer) or blue (winter) full-seated pantaloons. The pant-legs covered knee-length stockings, and ended in buttoned “spats” that kept dirt and mud out of the shoes.

At his back the enlisted man carried a wooden water canteen, probably painted red. Some may have carried a leather rifleman’s pouch, or “possibles bag,” and a knapsack or haversack for extra clothes and personal articles[2]Souvenir-collecting is a human impulse shared by many. Upon leaving “Canoe Camp” above the Great Falls of the Missouri, on their way west, Lewis complained: “We find it extreemly … Continue reading, with a blanket sometimes tied under the flap. At his hip were slung a bayonet and a tomahawk (hatchet).

Though it undoubtedly looked quite impressive from a distance, the enlisted man’s uniform was cheaply made, since the conservative government still placed a low value on its small, 3,000-man, standing army in 1803. After all, taxpayers believed, they had already won the ultimate war—the War for Independence.

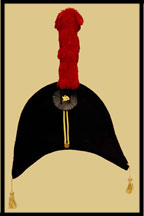

Enlisted Man’s Hat

Beaver-felt Military Hat with Bearskin, Cockade, and Plume[3]Re-creation by Robert Moore, Historian at Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, St. Louis; Peyton C. Clark; Greg Hudson, Weeping Heart Trade Company, Ehrlanger, Kentucky. Photos by Jon Stealey.

Between about 1794 and 1810, every enlisted infantryman was issued a tall hat—called a “round hat” in original documents—that stood about 5 inches high and had a two-inch brim. The dress version of this hat was decorated with a leather cockade and white laced strap, a white deer‘s tail, a strip of black bear’s fur running over the top, and white worsted trim around the brim. Artillerymen wore the more traditional three-cornered cocked hat laced with yellow worsted trim.[4]“Worsted” yarn is made of wool that has been combed to remove the short fibres, and make the remaining long fibres lie parallel so they can be twisted more tightly than the usual … Continue reading

According to modern military tradition, the gesture we call a salute originated in medieval times, with the raising of the armored knight’s visor. However, in the 18th century the proper gesture between gentlemen was a low bow accompanied by a sweeping removal of the hat.

During the Revolutionary War cavalrymen and light infantry men, who wore leather helmets, were permitted the simpler motion of raising the flat of the hand up to touch the brim. British soldiers used a similar gesture if not wearing cocked hats. Upon the introduction of the round hat, it was soon discovered that the old-fashioned doffing of the hat quickly broke down the stiff, narrow brim, so the abbreviated gesture became the preferred one.

Clark’s Dress Uniform

A steady process of replacing worn-out woven fatigues with leather clothing began when the Corps set out from Fort Mandan in April 1805, but by the time they reached the mouth of the Columbia River their leather attire was rotten and full of holes. Still, the captains held on to their dress uniforms because they were important in dealing with Indian tribes—the emblems of authority, counterparts of the Indian leaders’ ceremonial attire.

Throughout the expedition the officers wore their dress uniforms on special occasions such as parades and reviews, to reinforce pride and esprit de corps. They also wore them on official occasions such as courts-martial, and the burial of Sergeant Charles Floyd.

“Captain” Clark, who actually was a second lieutenant in the Corps of Artillerists during his duty with the expedition,[5]Clark had resigned his commission as a captain in the Infantry in 1796, to return to civilian life. President Jefferson had authorized Lewis to offer Clark a captain’s commission to serve as … Continue reading probably wore a dress uniform coat of blue and red wool, lined with red linen. The red turnback of the coat skirt signified an artillery officer, as did the 20 gold-plated buttons embossed with an image of an artillery gun and carriage, and the red sash. A white belt, held in place over the right shoulder by a gold epaulet, carried the officer’s sword.

Under his coat an officer wore “small clothes”—a knee-length flannel or linen pullover shirt, with ruffles at the neck and sleeves, was tucked into the waistband and between the legs of a pair of white “pantaloons.” No one yet wore what we know today as “underwear,” but the long shirt flaps fulfilled this function. The legs of the pantaloons, similar to modern trousers except for the fact that they were cut very full in the seat, covered knee length stockings, and over them an officer wore a pair of black boots.

Photo courtesy Peyton C. Clark[6]Re-creation by Robert Moore, Historian, Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, St. Louis; Peyton C. Clark; and Greg Hudson, Weeping Heart Trade Company, Ehrlanger, Kentucky. Photos by Mike Venso.

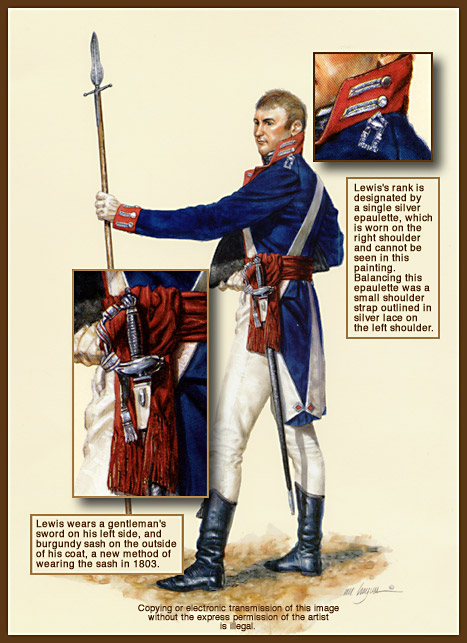

Lewis’s Dress Uniform

Captain Meriwether Lewis, 1st U.S. Infantry Regiment

Historic Art by Michael Haynes—Text by Bob Moore

Details enlarged by David Nelson

Prints of the entire collection Michael Haynes’s paintings of uniforms worn by the Corps of Discovery are available direct from the artist.

Beaver-felt chapeau bras[7]Re-creation by Robert Moore, Historian at Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, St. Louis; Peyton C. Clark; Greg Hudson, Weeping Heart Trade Company, Ehrlanger, Kentucky. Photos by Jon Stealey.

With embossed leather cockade,

plume, gold cord and gold tassels

Evidently one pair of Lewis’s uniform pants were of satin, for he recorded that on 3 January 1806, he gave the Clatsop chief, Coboway, “a pare of sattin breechies with which he appeared much pleased.” The gold trim of Clark’s coat was made of thread wrapped with fine gold wire.

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, military styles and fashions continued to evolve. One example of this evolution was the beaver felt hat. By the early 1700s, the older style flop hats were turned up on the sides to prevent windy gusts from blowing them off the heads of soldiers and officers .often taking the wigs of officers along with them! By the 1740s and ’50s old floppy acquired the shape of an equilateral triangle when seen from above. This shape changed to a triangle flattened across the front by the time of the American Revolution, becoming narrower and narrower until by 1800 the hat had but two sides instead of three. This new hat was properly calle a chapeau bras, or “arm hat,” but was often was referred to as a “cocked hat.” Convenient to carry folded under one arm, the chapeau bras measured about 23 inches between tips, and stood about 7 1/2 inches from the forehead to the top.

Beaver hats were favored by civilian as well as military men throughout Europe and the U.S. because they were sturdy and waterproof. The cloth was crafted from the fine underfur, or “wool,” shaved from beaver pelts and separated from the coarser hair by a blowing process.

The softer fur was gradually applied to a revolving, perforated copper cone with the aid of a suction device, and smoothed with the hands. With the application of a spray of hot water, the fur fibers began to mat together into a durable fabric called “felt.” The cone of wet fur was then transferred to a hat mold while still soft and warm, and worked into the desired shape. When the felt was dry, shellac was applied to the inside of the hat to help hold the shape. The outside was then polished to a glossy finish with brushes, irons, or sandpaper.

The shaved beaver skins were used in the manufacture of glue; the coarse outer hair was used in furniture upholstery.

Further Reading

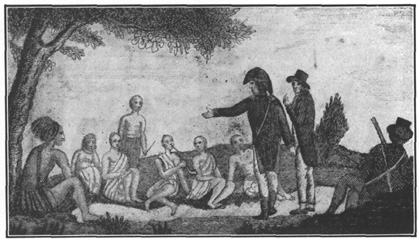

Officer in Action

“The First Council with the Indians

Held by Lewis and Clark”

Courtesy Missouri Historical Society

Engraving (artist unknown) from Journal of the Voyages and Travels of a Corps of Discovery, by Patrick Gass (Philadelphia: Mathew Carey, 1810)

Robert J. Moore, Jr., “The Clothing of the Lewis & Clark Expedition,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 20, No. 3 (August 1994), 4-13.

___________, and Michael Haynes, Tailor Made, Trail Worn: Army Life, Clothing & Weapons of the Corps of Discovery (Helena, Montana: Farcountry Press, 2003, 121-36.

Notes

| ↑1 | Re-creation by Robert Moore, Historian at Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, St. Louis; Peyton C. Clark; Greg Hudson, Weeping Heart Trade Company, Ehrlanger, Kentucky. Photos by Jon Stealey. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Souvenir-collecting is a human impulse shared by many. Upon leaving “Canoe Camp” above the Great Falls of the Missouri, on their way west, Lewis complained: “We find it extreemly difficult to keep the baggage of many of our men within reasonable bounds; they will be adding bulky articles of but little use or value to them.” |

| ↑3 | Re-creation by Robert Moore, Historian at Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, St. Louis; Peyton C. Clark; Greg Hudson, Weeping Heart Trade Company, Ehrlanger, Kentucky. Photos by Jon Stealey. |

| ↑4 | “Worsted” yarn is made of wool that has been combed to remove the short fibres, and make the remaining long fibres lie parallel so they can be twisted more tightly than the usual full-bodied wool yarns. |

| ↑5 | Clark had resigned his commission as a captain in the Infantry in 1796, to return to civilian life. President Jefferson had authorized Lewis to offer Clark a captain’s commission to serve as co-commander of the expedition. Unfortunately, the reduction in the size of the standing army had eliminated some officers, and no new appointments could be ranked above men of greater longevity. The only berth available was a lieutenancy in the Corps of Artillerists. Lewis, however, treated Clark as his co-captain without letting on otherwise to the enlisted men. Clark was finally granted a retroactive promotion to the rank of captain by President William Jefferson Clinton on 17 January 2001. See Donald Jackson, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854, 2nd ed., 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 60, 172-73. |

| ↑6 | Re-creation by Robert Moore, Historian, Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, St. Louis; Peyton C. Clark; and Greg Hudson, Weeping Heart Trade Company, Ehrlanger, Kentucky. Photos by Mike Venso. |

| ↑7 | Re-creation by Robert Moore, Historian at Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, St. Louis; Peyton C. Clark; Greg Hudson, Weeping Heart Trade Company, Ehrlanger, Kentucky. Photos by Jon Stealey. |