Sergeant in Dress Uniform

© Michael Haynes, https://www.mhaynesart.com. Used with permission.

The soldier depicted here wears the full dress uniform of an infantry sergeant. As a recruit from Kentucky, Sergeant Pryor would not have previously owned such a uniform, nor is it known if he was issued one. Sergeants carried swords and their uniforms included a single epaulette on the shoulder and a sash around the abdomen.[1]Robert J. Moore, Jr. and Michael Haynes, Lewis & Clark: Tailor Made, Trail Worn (Helena: Far Country Press, 2003), 18.

Sandy River

© 2012 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Marias River

© 28 June 2013 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

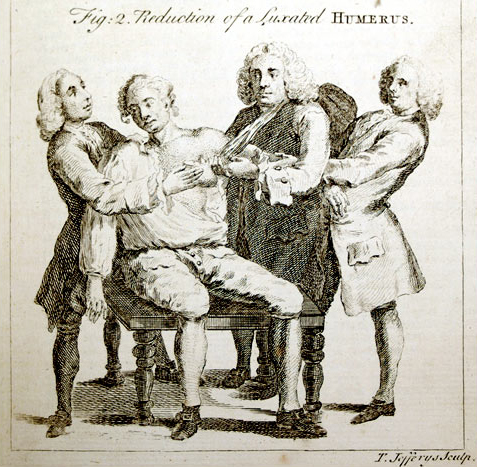

Illustration from Owen’s Dictionary

Owen’s Dictionary, from Special Collections, Watzek Library, Lewis and Clark College, Portland, Oregon

“Humerus, in anatomy, the upper part of the arm, between the scapula and elbow. . . . This bone, from the length and laxity of its ligaments, the largeness of its motion, and the shallowness of the cavity in the scapula in which it is articulated, is very subject to be luxated [dislocated].

“As soon as this is discovered to be the case, the patient should be seated on the floor, or on a low stool, while two assistants stretch his arm; which being sufficiently extended, the surgeon ought to elevate the head of the humerus by means of a napkin, hung about his neck, and put under the arm-pit; and at the same time move it backward and forward, as he shall see occasion, till it is happily reduced into its place.”[2]A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences . . . (London: Printed for W. Owen, at Homer’s Head, in Fleet-street, 1764), s.v. Humerus.

Both of the captains had gained enough experience in the army—Clark, for instance, had commanded a mid-winter keelboat voyage up the Wabash River to Vincennes—that they probably had coped with this process before, and didn’t need to consult Owen’s Dictionary.

“A man of character and ability”

Nathaniel Hale Pryor was born in Amherst County, Virginia, about forty miles southwest of Charlottesville and Monticello, in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. No record of his birth date has been found, but he probably was about the same age as his cousin, Charles Floyd, who was born in 1782.[3]Raymond W. Settle, “Nathaniel Pryor,” in LeRoy R. Hafen, ed., The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West. 10 vols. (Glendale, Calif.: Arthur H. Clark, 1965), 2, 277. His family moved to Louisville, in frontier Kentucky, when he was eleven, and he joined the expedition on October 20, 1803, at Clarksville, Indiana—one of nine recruits from Kentucky. In 1798 he had married Margaret Patton, but a descendant, John H. Pryor, speculates that since Lewis had instructed Clark to take only unmarried men, his recruitment suggests that either Margaret had died, or else the two were divorced by that time.[4]Alexander Willard, another former member of the Corps of Discovery, was en route from St. Louis to warn Pryor, but didn’t arrive in time.

It may be that Pryor had some talent as a carpenter, for during the construction of Camp Dubois he supervised the men assigned to saw planks, and he oversaw the repairs of two Indian canoes they purchased shortly before their departure from Fort Clatsop. He accompanied Lewis on the exploration of the lower Marias River in early June of 1805. On April 1, 1806, he and two privates explored six miles up the Quicksand (today’s Sandy) River, which meets the Columbia at Troutdale, east of Portland, Oregon. Later that same year, traveling down the Yellowstone River, Clark assigned Pryor to lead a command trying to take horses to trade for supplies at Fort Assiniboine in Canada. (See Pryor’s Mission.)

Landmarks

Pryor’s name was frequently on the captains’ minds when naming landmarks. They put it on three different creeks in the vicinity of present Helena, Montana, but other names soon fell into place.[5]White Earth Creek (Beaver Creek today), Prickly Pear Creek, and Spokane Creek. Moulton, Journals, 4:405, 412, 417. Clark, who called Pryor “a steady valuable and usefull member of our party,” absent-mindedly named two tributaries of the Yellowstone River for him: “Pryers river” (today’s Dry Creek, at river mile 379) and “Pryor’s River” (today’s Pryor Creek), at river mile 349.9)[6]Moulton, Atlas, maps 108 and 116.

Pryor’s Trick Shoulder

With all the heavy lifting and carrying of heavy supplies and equipment under adverse and hazardous conditions, with all the manhandling of the barge, pirogues, and canoes, and with all the falls and other accidents the men were subject to, there must have been many sprains, bruises, and contusions, only a few of which the journalists saw fit to mention. Two of the enlisted men, however, were subject particular physical disability, however. Both Sergeant Pryor and Private George Gibson were prone to dislocated shoulders.

The first occurrence was at Fort Mandan on 29 November 1804, when Clark recorded “Sergeant Pryor in takeing down the mast put his Sholder out of Place.” It took four tries to “reduce” it. It happened to him again on 23 August 1805, under unknown circumstances. On 25 May 1805, Sergeant Gass mentioned that Gibson had suffered the same injury.)

Evidently Pryor’s trick shoulder proved a serious enough handicap to justify special consideration much later. On 4 August 1827 Clark wrote to James Barbour (1775-1842), Secretary of War under President John Quincy Adams, to inform him that as Superintendent of Indian Affairs he had hired Nathaniel Pryor as Sub Agent and Interpreter to the Osage tribe on the basis of “his influence among the Indians generally, in that quarter, his capacity to act and be serviceable, added to his knowledge of the Osage language.” There were two more factors in his favor:

Capt. Pryor’s long and faithful services and his being disabled by a dislocation of his shoulder when in the execution of his duty under my command, produces an interest in his favor and much solicitude for bettering his situation by an office which he is every way capable of filling with credit to himself and usefulness to his government.[7]Jackson, Letters, 2:645-46. Pryor had stayed in the army after the expedition and following the War of 1812 had retired as a captain and had tried unsuccessfully to make a living in the Indian trade.

Trader

Nathaniel Pryor was promoted to the rank of ensign (second lieutenant) in the First Infantry after the expedition’s close. He left the army in 1810 to become a trader but had some unfortunate encounters with Indians.

Licensed by Governor Clark to trade with the Winnebago Indians, he quickly established a profitable business, including a smelting furnace at Julien Dubuque’s lead mines in Iowa, “and was rapidly distributing through the Tribes the comforts and conveniences of civilization.” Clark asked him to try to locate Tecumseh, or the Prophet, which roused the “hostility and enmity” and murderous intent of the Winnebagos following the Battle of Tippecanoe. It was winter, and while an Indian woman in Pryor’s house distracted his executioners, he fled across the Mississippi on the ice. The Indians killed two of his men, stole all his personal property and trade goods, and destroyed everything else. Later he filed a claim against the government, on the grounds he did not know of the Indian unrest, but modestly limited his demands to the actual value of the lost goods, $5,216.25. Writing in his behalf to Secretary of War James Barbour fourteen years after the event, his friend Franklin Wharton called Pryor “a man of real, solid, innate worth,” whose “genuine modesty conceals the peculiar traits of his character.” He was, Wharton also said, “a brave and persevering officer in the attack on New Orleans.”[8]Jackson, Letters, 1:640–43. Jackson, Among the Sleeping Giants: Occasional Pieces on Lewis and Clark (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 111.

Captain and Indian Subagent

Pryor re-enlisted, and saw action in the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812.In August of 1813 he was commissioned first lieutenant in the Forty-fourth Infantry, and one month later was promoted to captain, seeing action in the Battle of New Orleans on 8 January 1815. In June he was honorably discharged from the army and returned to the Indian trade, opening a post on the lower Arkansas River, among the Osages. Like his previous commercial ventures, this one saw but limited success. In 1821 Pryor established another trading post on the Canadian River, married an Osage woman, and served for several years as an unofficial, unpaid interpreter and mediator for her people. Highly respected by Indians, military authorities, government officials and others, in 1830 Governor Clark appointed him temporary subagent for Clermont’s band of Osages at $500 per year. He failed to step up into a permanent appointment.

Pryor died in June of 1831, at about age forty-nine.

Notes

| ↑1 | Robert J. Moore, Jr. and Michael Haynes, Lewis & Clark: Tailor Made, Trail Worn (Helena: Far Country Press, 2003), 18. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences . . . (London: Printed for W. Owen, at Homer’s Head, in Fleet-street, 1764), s.v. Humerus. |

| ↑3 | Raymond W. Settle, “Nathaniel Pryor,” in LeRoy R. Hafen, ed., The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West. 10 vols. (Glendale, Calif.: Arthur H. Clark, 1965), 2, 277. |

| ↑4 | Alexander Willard, another former member of the Corps of Discovery, was en route from St. Louis to warn Pryor, but didn’t arrive in time. |

| ↑5 | White Earth Creek (Beaver Creek today), Prickly Pear Creek, and Spokane Creek. Moulton, Journals, 4:405, 412, 417. |

| ↑6 | Moulton, Atlas, maps 108 and 116. |

| ↑7 | Jackson, Letters, 2:645-46. Pryor had stayed in the army after the expedition and following the War of 1812 had retired as a captain and had tried unsuccessfully to make a living in the Indian trade. |

| ↑8 | Jackson, Letters, 1:640–43. Jackson, Among the Sleeping Giants: Occasional Pieces on Lewis and Clark (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 111. |