Another geomorphic landmark noted by the captains was Hat Rock, an outcropping of the Pomona Member of the Saddle Mountain Basalt. See Columbia River Basalts

—John W. Jengo[1]John W. Jengo, “After the Deluge: Flood Basalts, Glacial Torrents, and Lewis and Clark’s “Swelling, boiling & whorling” River Route to the Pacific,” We Proceeded On, August … Continue reading

Working hard to stay ahead of the current, on 19 October 1805, the Corps of Discovery paddled an estimated thirty-six miles in four compass courses. The first, starting at their camp near the mouth of the Walla Walla River, was the longest: “S.W. 14 miles to a rock in a Lard.”—the larboard, or left side of the river—”resembling a hat.” Just a casual nod toward an object that two centuries later would be one of the few Lewis and Clark landmarks left above water, but the enlisted men must have recognized it at a glance, this pile of columnar basalt, its little chunks of chilled lava resembling cans carelessly stacked on a pantry shelf, all together resembling a well-weathered gentleman’s hat with a work-worn brim. It was left behind by the shuddering floods from twenty or more emptyings of vast Glacial Lake Missoula a mere fifteen to thirteen thousand years ago.[2]David Alt, Glacial Lake Missoula’s Humongous Floods (Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press, 2001), 153. It rises a hundred feet above the sagebrush on a low hill by the shore of Lake Wallula, the broad slackwater pool backed up behind McNary Dam, seven miles downstream.

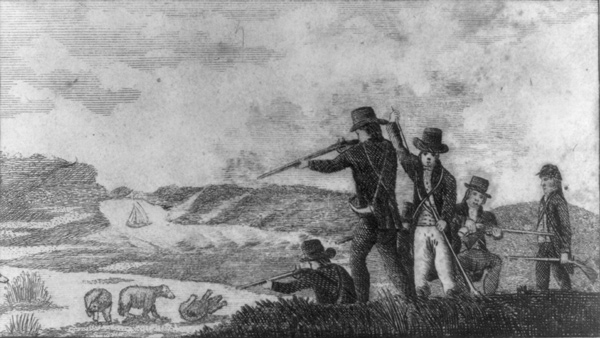

Each of the six quaint, primitivistic drawings that publisher Mathew Cary included in Patrick Gass‘s Journal of the Voyages and Travels of a Corps of Discovery, portrays the enlisted men wearing the “round hat” that was official U.S. Army infantry headgear from 1794 until 1810.[3]Patrick Gass, A Journal of the Voyages and Travels of a Corps of Discovery (Pittsburgh: Mathew Carey, 1810). The three-cornered Revolutionary-era chapeaus we see in so many old paintings of episodes from the expedition, and even on the official National Historic Trail symbol, were worn only by artillerymen until the War of 1812.

Yes, as an army officer on the expedition, Clark was not restored to the rank of infantry captain as had been promised by President Jefferson, but was officially a lieutenant in the artillery. (See Clark’s Commission) That affront rankled him for the rest of his days. No, he would not have stooped to wearing an artillerists hat in front of the Corps’ enlisted men. Never!

Hat Rock is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. The rock can be visited at Hat Rock State Park, Oregon.—ed.

Notes

| ↑1 | John W. Jengo, “After the Deluge: Flood Basalts, Glacial Torrents, and Lewis and Clark’s “Swelling, boiling & whorling” River Route to the Pacific,” We Proceeded On, August 2014, Volume 40, No. 3, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original article is provided at https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol40no3.pdf#page=9. See also on this site, Columbia River Geology. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | David Alt, Glacial Lake Missoula’s Humongous Floods (Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press, 2001), 153. |

| ↑3 | Patrick Gass, A Journal of the Voyages and Travels of a Corps of Discovery (Pittsburgh: Mathew Carey, 1810). |